Chapter Seven the Medieval Universities of Oxford and Paris

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

31Higher Education

Educación ess Superior y Sociedad Higher Education in the Caribbean 311 Instituto Internacional de Unesco para la Educación Superior en América Latina y el Caribe (IESALC), 2019-II Educación Superior y Sociedad (ESS) Nueva etapa Vol. 31 ISSN 07981228 (formato impreso) ISSN 26107759 (formato digital) Publicación semestral EQUIPO DE PRODUCCIÓN Débora Ramos Ayumarí Rodríguez Enrique Ravelo José Antonio Vargas Sara Maneiro Yara Bastidas Zulay Gómez José Quinteiro Yeritza Rodríguez CORRECCIÓN DE ESTILO Annette Insanally DIAGRAMACIÓN Pedro Juzgado A. TRADUCCIÓN Yara Bastidas Apartado Postal Nª 68.394 Caracas 1062-A, Venezuela Teléfono: +58 - 212 - 2861020 E-mail: [email protected] / [email protected] 2 CONSEJO EDITORIAL INTERNACIONAL • Rectores Dra. Alta Hooker Rectora de la Universidad de las Regiones Autónomas de la Costa Caribe Nicaragüense Dr. Benjamín Scharifker Podolsky Rector Metropolitana, Venezuela Dr. Emilio Rodríguez Ponce Rector de la Universidad de Tarapacá, Chile Dr. Francisco Herrera Rector Universidad Nacional Autónoma de Honduras Dr. Ricardo Hidalgo Ottolenghi Rector UTE Padre D. Ramón Alfredo de la Cruz Baldera Pontificia Universidad Católica Madre y Maestra, República Dominicana Dr. Rita Elena Añez Rectora Universidad Nacional Experimental Politécnica “Antonio José de Sucre” Dr. Waldo Albarracín Rector Universidade Mayor de San Andrés, Bolivia Dr. Freddy Álvarez González Rector de la Universidad Nacional de Educación -UNAE Dra. Sara Deifilia Ladrón de Guevara González Universidad Veracruzana, México • Expertos e investigadores -

Linus J. Guillory Jr., Phd, Chief Schools Officer DATE

Linus J. Guillory Jr., PhD LOWELL PUBLIC SCHOOLS Chief Schools Officer Phone: (978) 674-2163 155 Merrimack Street E-mail: [email protected] Lowell, Massachusetts 01852 TO: Dr. Joel Boyd, Superintendent of Schools FROM: Linus J. Guillory Jr., PhD, Chief Schools Officer DATE: September 27, 2019 RE: Update on the Latin Lyceum The following report is in response to a motion by Gerard Nutter & Andy Descoteaux: Administration to explain the change in philosophy regarding class location for the Latin Lyceum and Freshman Academy. Robert DeLossa prepared a response for Head of Lowell High School Busteed. The entirety of the response is reflected herein. From: Robert DeLossa To: Marianne Busteed Date: 25 September 2019 RE: Response to School Committee Motion with regard to the change of Freshman location to FA for Lyceum Students With regard to the question of whether the decision to house the teachers of Freshman Lyceum students in the Freshman Academy reflected a change of philosophy underlying the Lowell Latin Lyceum, I can state categorically that it did not. The underlying philosophy of the LLL remains the same as it has since the beginning of the Lyceum. Below I will point to two different areas to consider. The first is that the move to the Freshman Academy actually is more consistent with the philosophy of the Lyceum than the previous arrangement. Second, the move to the Freshman Academy better supports the individual needs of Lyceum students, who because of their academic giftedness and creativity, often need more social-emotional support than the previous arrangement provided. That support is physically located in the Freshman Academy. -

Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France

KNOWLEDGE COMMUNITIES Lynch Education in Late Medieval France Elementary and Grammar Sarah B. Lynch Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Lyon, 1285-1530 Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Knowledge Communities This series focuses on innovative scholarship in the areas of intellectual history and the history of ideas, particularly as they relate to the communication of knowledge within and among diverse scholarly, literary, religious, and social communities across Western Europe. Interdisciplinary in nature, the series especially encourages new methodological outlooks that draw on the disciplines of philosophy, theology, musicology, anthropology, paleography, and codicology. Knowledge Communities addresses the myriad ways in which knowledge was expressed and inculcated, not only focusing upon scholarly texts from the period but also emphasizing the importance of emotions, ritual, performance, images, and gestures as modalities that communicate and acculturate ideas. The series publishes cutting-edge work that explores the nexus between ideas, communities and individuals in medieval and early modern Europe. Series Editor Clare Monagle, Macquarie University Editorial Board Mette Bruun, University of Copenhagen Babette Hellemans, University of Groningen Severin Kitanov, Salem State University Alex Novikoff, Fordham University Willemien Otten, University of Chicago Divinity School Elementary and Grammar Education in Late Medieval France Lyon, 1285-1530 Sarah B. Lynch Amsterdam University Press Cover illustration: Aristotle Teaching in Aristotle’s Politiques, Poitiers, 1480-90. Paris, BnF, ms fr 22500, f. 248 r. Cover design: Coördesign, Leiden Lay-out: Crius Group, Hulshout Amsterdam University Press English-language titles are distributed in the US and Canada by the University of Chicago Press. isbn 978 90 8964 986 7 e-isbn 978 90 4852 902 5 (pdf) doi 10.5117/9789089649867 nur 684 © Sarah B. -

One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: a History of the Church in the Middle Ages

ONE , H OLY , CATHOLIC , AND APOSTOLIC : A H ISTORY OF THE CHURCH IN THE MIDDLE AGES COURSE GUIDE Professor Thomas F. Madden SAINT LOUIS UNIVERSITY One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: A History of the Church in the Middle Ages Professor Thomas F. Madden Saint Louis University Recorded Books ™ is a trademark of Recorded Books, LLC. All rights reserved. One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: A History of the Church in the Middle Ages Professor Thomas F. Madden Executive Producer John J. Alexander Executive Editor Donna F. Carnahan RECORDING Producer - David Markowitz Director - Matthew Cavnar COURSE GUIDE Editor - James Gallagher Contributing Editor - Karen Sparrough Design - Edward White Lecture content ©2006 by Thomas F. Madden Course guide ©2006 by Recorded Books, LLC 72006 by Recorded Books, LLC Cover image: Basilica of Notre Dame Cathedral, Paris © Clipart.com #UT095 ISBN: 978-1-4281-3777-6 All beliefs and opinions expressed in this audio/video program and accompanying course guide are those of the author and not of Recorded Books, LLC, or its employees. Course Syllabus One, Holy, Catholic, and Apostolic: A History of the Church in the Middle Ages About Your Professor ................................................................................................... 4 Introduction ................................................................................................................... 5 Lecture 1 Birth of the Medieval Church ................................................................. 6 Lecture 2 The Church in an Age of -

Partner Schools Art & Design

Art&Design Partner Institutions Erasmus Code Country City Institute A LINZ02 Austria Linz University of Art and Design A WIEN07 Austria Vienna University of Applied Arts Vienna ARTESIS PLANTIJN HOGESCHOOL B ANTWERP62 Belgium Antwerpen ANTWERPEN Brugge / Vives Katholieke Hogeschool Brugge - B BRUGGE11 Belgium Oostende Oostende B BRUSSEL43 Belgium Brussels/Ghent LUCA ( vroeger Hogeschool Sint-Lukas Brussel) B GENT25 Belgium Ghent Hogeschool Gent, School of Arts – KASK B HASSELT22 Belgium Hasselt PIXL University College Film and tv school of Academy of performing CZ PRAHA04 Czech Republic Prague arts in Prague (FAMU) D BRAUNSC02 Germany Braunschweig Hochschule für Bildende Künste Braunschweig D DUSSELD03 Germany Dusseldorf Fachhochschule Düsseldorf D HALLE03 Germany Halle Burg Giebichenstein Kunsthochschule Halle Staatliche Hochschule fur Gestaltung D KARLSRU06 Germany Karlsruhe Karlsruhe D KOBLENZ01 Germany Koblenz UNIVERSITY OF APPLIED SCIENCES KOBLENZ D MAINZ08 Germany Mainz Fachhochschule Mainz Schwäbisch D SCHWA02 Germany Hochschule für Gestaltung Schwäbisch Gmünd Gmünd D TRIER02 Germany Trier Hochschule Trier DK Denmark Kopenhagen Danmarks Designskole KOBENHA59 DK Denmark Kolding Kolding School of Design KOLDING07 E BARCELO02 Spain Barcelona Escola Massana Centre d'Art i Disseny E CIUDAR 01 Spain Cuenca Universidad de Castilla la Mancha (UCLM) Version January 2020 E MADRID03 Spain Madrid Universidad Complutense de Madrid E MADRID197 Spain Madrid Centro Universitario de Artes TAI La Escola d'Art i Superior de Disseny de E VALENCI13 Spain -

Opportunities for Teaching and Studying Medicine in Medieval Portugal Before the Foundation of the University of Lisbon (1290)(*)

Opportunities for Teaching and Studying Medicine in Medieval Portugal before the Foundation of the University of Lisbon (1290)(*) IONA McCLEERY (**) ABSTRACT This paper discusses where Portuguese physicians studied medicine. The careers of two thirteenth-century physicians, Petrus Hispanus and Giles of Santarém, indicate that the Portuguese travelled abroad to study in Montpellier or Paris. But it is also possible that there were opportunities for study in Portugal itself. Particularly significant in this respect is the tradition of medical teaching associated with the Augustinian house of Santa Cruz in Coimbra and the reference to medical texts found in Coimbra archives. From these sources it can be shown that there was a suitable environment for medical study in medieval Portugal, encouraging able students to further their medical interests elsewhere. BIBLID [0211-9536(2000) 20; 305-329] Fecha de aceptación: 8 de marzo de 1998 (*) A version of this paper was delivered at the «Medical Teaching» conference at King’s College, Cambridge on 7-9 January 1998. I would like to thank Roger French for inviting me to take part in the conference, and Cornelius O’Boyle, Michael McVaugh, Tessa Webber, Charles Burnett, Miguel de Asua, Klaus-Dietrich Fischer, and Tiziana Pesenti for their comments and encouragement during the conference. Further thanks go to my friends and office mates Julie Kerr, Angus Stewart, Haki Antonsson and Björn Weiler, who have kept me going throughout my studies. Finally, I am very grateful to my supervisor, Simone Macdougall, who read a draft of this paper at short notice, and whose advice and suggestions are greatly appreciated. -

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education

Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education: Challenges and Opportunities American Council of Learned Societies ACLS OCCASIONAL PAPER, No. 59 In Memory of Christina Elliott Sorum 1944-2005 Copyright © 2005 American Council of Learned Societies Contents Introduction iii Pauline Yu Prologue 1 The Liberal Arts College: Identity, Variety, Destiny Francis Oakley I. The Past 15 The Liberal Arts Mission in Historical Context 15 Balancing Hopes and Limits in the Liberal Arts College 16 Helen Lefkowitz Horowitz The Problem of Mission: A Brief Survey of the Changing 26 Mission of the Liberal Arts Christina Elliott Sorum Response 40 Stephen Fix II. The Present 47 Economic Pressures 49 The Economic Challenges of Liberal Arts Colleges 50 Lucie Lapovsky Discounts and Spending at the Leading Liberal Arts Colleges 70 Roger T. Kaufman Response 80 Michael S. McPherson Teaching, Research, and Professional Life 87 Scholars and Teachers Revisited: In Continued Defense 88 of College Faculty Who Publish Robert A. McCaughey Beyond the Circle: Challenges and Opportunities 98 for the Contemporary Liberal Arts Teacher-Scholar Kimberly Benston Response 113 Kenneth P. Ruscio iii Liberal Arts Colleges in American Higher Education II. The Present (cont'd) Educational Goals and Student Achievement 121 Built To Engage: Liberal Arts Colleges and 122 Effective Educational Practice George D. Kuh Selective and Non-Selective Alike: An Argument 151 for the Superior Educational Effectiveness of Smaller Liberal Arts Colleges Richard Ekman Response 172 Mitchell J. Chang III. The Future 177 Five Presidents on the Challenges Lying Ahead The Challenges Facing Public Liberal Arts Colleges 178 Mary K. Grant The Importance of Institutional Culture 188 Stephen R. -

Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination Jessica Rezunyk Washington University in St

Washington University in St. Louis Washington University Open Scholarship Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations Arts & Sciences Winter 12-15-2015 Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination Jessica Rezunyk Washington University in St. Louis Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds Recommended Citation Rezunyk, Jessica, "Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination" (2015). Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations. 677. https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/art_sci_etds/677 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Arts & Sciences at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Arts & Sciences Electronic Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. WASHINGTON UNIVERSITY IN ST. LOUIS Department of English Dissertation Examination Committee: David Lawton, Chair Ruth Evans Joseph Loewenstein Steven Meyer Jessica Rosenfeld Science and Nature in the Medieval Ecological Imagination by Jessica Rezunyk A dissertation presented to the Graduate School of Arts & Sciences of Washington University in partial fulfillment of the degree of Doctor of Philosophy December 2015 St. Louis, Missouri © 2015, Jessica Rezunyk Table of Contents List of Figures……………………………………………………………………………. iii Acknowledgments…………………………………………………………………………iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………………………vii Chapter 1: (Re)Defining -

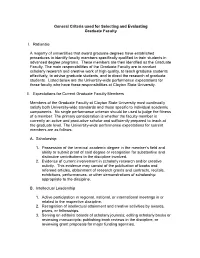

General Criteria Used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I

General Criteria used for Selecting and Evaluating Graduate Faculty I. Rationale A majority of universities that award graduate degrees have established procedures to identify faculty members specifically qualified to train students in advanced degree programs. These members are then identified as the Graduate Faculty. The main responsibilities of the Graduate Faculty are to conduct scholarly research and creative work of high quality, to teach graduate students effectively, to advise graduate students, and to direct the research of graduate students. Listed below are the University-wide performance expectations for those faculty who have these responsibilities at Clayton State University. II. Expectations for Current Graduate Faculty Members Members of the Graduate Faculty at Clayton State University must continually satisfy both University-wide standards and those specific to individual academic components. No single performance criterion should be used to judge the fitness of a member. The primary consideration is whether the faculty member is currently an active and productive scholar and sufficiently prepared to teach at the graduate level. The University-wide performance expectations for current members are as follows: A. Scholarship 1. Possession of the terminal academic degree in the member’s field and ability to submit proof of said degree or recognition for substantive and distinctive contributions to the discipline involved. 2. Evidence of current involvement in scholarly research and/or creative activity. This evidence may consist of the publication of books and refereed articles, obtainment of research grants and contracts, recitals, exhibitions, performances, or other demonstrations of scholarship appropriate to the discipline. B. Intellectual Leadership 1. Active participation in regional, national, or international meetings in or related to the respective discipline. -

John Pecham on Life and Mind Caleb G

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations 2014 John Pecham on Life and Mind Caleb G. Colley University of South Carolina - Columbia Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Philosophy Commons Recommended Citation Colley, C. G.(2014). John Pecham on Life and Mind. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/ 2743 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. JOHN PECHAM ON LIFE AND MIND by Caleb Glenn Colley ! Bachelor of Arts Freed-Hardeman !University, 2006 Bachelor of Science Freed-Hardeman !University, 2006 Master of Liberal Arts ! Faulkner University, 2009 ! ! Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Philosophy College of Arts and Sciences University of South Carolina 2014 Accepted by: Jeremiah M.G. Hackett, Major Professor Jerald T. Wallulis, Committee Member Heike O. Sefrin-Weis, Committee Member Gordon A. Wilson, Committee Member Lacy Ford, Vice Provost and Dean of Graduate Studies ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! © Copyright by Caleb Glenn Colley, 2014 All Rights !Reserved. !ii ! ! ! ! DEDICATION To my parents, who have always encouraged and inspired me. Et sunt animae vestrae quasi mea. ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! ! !iii ! ! ! ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS A number of people have spent generous amounts of time and energy to assist in the preparation of this dissertation. Professor Girard J. Etzkorn, the editor of Pecham’s texts, is not listed as a committee member, but he read my manuscript in its early form and made many helpful suggestions. -

Decoding the Statutes of Gregory IX for the University of Paris 1231

Decoding The Statutes of Gregory IX for the University of Paris 1231 What had motivated Gregory IX's interest in the University of Paris? The Statutes of Gregory IX 1 for the University of Paris 1231 2 define the new rights and privileges of the teachers and students and help stopping the exodus of the teachers and students from the University, particularly for Oxford. It serves to ratify with immediacy as per a perceived denial 3 of justice, which had been sanctioned by Queen Blanche in 1229 and resulted in the teachers’ 2-year suspension of their teaching for the courses in retaliation. 4 Well-versed in the political situation of Europe 5, Pope Gregory IX’s 6 worries seem well-founded an exodus of teachers and students from The University of Paris does happen before the enactment of The Statutes. The teacher-student exodus in Europe has always been a widespread phenomenon.7 Gregory XI’s bestow on students’ right and privileges may well be his being a past student of The University of Paris, but his strong stance in anti-hereticism might point to his intended control over the teachers and students 8 carries much water. While no ulterior motive could justly be implied to Gregory IX, as a nephew of the 1 Based on the translation from Dana C. Munro, trans., University of Pennsylvania Translations and Reprints , (Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 1897), Vol. II: No. 3, pp. 7-11 2 Hereafter called The Statutes. 3 The trouble originated in a quarrel in an inn in Paris which developed into a fight between the students and the citizens of Paris. -

Erasmus + Agreement

Annex to Erasmus+ Inter-Institutional Agreement Institutional Factsheet 1. Institutional Information 1.1. Institutional details Name of the institution Université Paris Diderot – Paris 7 Erasmus Code F PARIS007 EUC Nr. 28258 Institution website http://www.univ-paris-diderot.fr Online course catalogue / 1.2. Main contacts Contact person Jan DOUAT* Responsibility Central management of the Erasmus+ program Contact person for Erasmus+ partners Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 59 53 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 Email: [email protected] Contact person Floriane THOREZ* Responsibility Contact person for incoming students / Internships Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 55 05 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 - Email: [email protected] Contact person Valérie BEAUDOIN* Responsibility Contact person for outgoing students Contact details Phone: +33 1 57 27 55 34 - Fax: +33 1 57 27 55 07 - Email: [email protected] The email address will remain identical even in the case of a turnover Annex to Erasmus + Inter-Institutional Agreement | Institutional Factsheet Page 1 / 4 2. Detailed requirements and additional information 2.1. Recommended language skills Following agreement with our institution, the sending institution is responsible for providing support to its nominated candidates so that they can have the recommended language skills at the start of the study or teaching period: COURSES ARE TAUGHT IN FRENCH Type of mobility Subject area Language(s) of instruction Recommended language of instruction