Tasteful Piano Performance in Classic-Era Britain

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Schubert and Liszt SIMONE YOUNG’S VISIONS of VIENNA

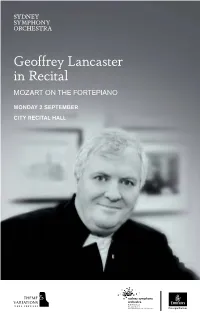

Schubert and Liszt SIMONE YOUNG’S VISIONS OF VIENNA 21 – 24 AUGUST SYDNEY OPERA HOUSE CONCERT DIARY NEW SEASON AUGUST Beethoven and Brahms Cocktail Hour Fri 23 Aug, 6pm BEETHOVEN String Quartet in E minor, Sat 24 Aug, 6pm Op.59 No.2 (Razumovsky No.2) Sydney Opera House, BRAHMS String Quintet No.2 Utzon Room Musicians of the Sydney Symphony Orchestra Abercrombie & Kent Shostakovich Symphony No.4 Masters Series JAMES EHNES PLAYS KHACHATURIAN Wed 28 Aug, 8pm KHACHATURIAN Violin Concerto Fri 30 Aug, 8pm SHOSTAKOVICH Symphony No.4 Sat 31 Aug, 8pm Sydney Opera House Mark Wigglesworth conductor James Ehnes violin SEPTEMBER Geoffrey Lancaster in Recital Mon 2 Sep, 7pm City Recital Hall MOZART ON THE FORTEPIANO MOZART Piano Sonata in B flat, K570 MOZART Piano Sonata in E flat, K282 MOZART Rondo in A minor, K511 MOZART Piano Sonata in B flat, K333 Geoffrey Lancaster fortepiano Music from Swan Lake Wed 4 Sep, 7pm Thu 5 Sep, 7pm BEAUTY AND MAGIC Concourse Concert Hall, ROSSINI The Thieving Magpie: Overture Chatswood RAVEL Mother Goose: Suite TCHAIKOVSKY Swan Lake: Suite Umberto Clerici conductor Star Wars: The Force Awakens Sydney Symphony Presents Thu 12 Sep, 8pm in Concert Fri 13 Sep, 8pm Watch Wednesdays 8.30pm Set 30 years after the defeat of the Empire, Sat 14 Sep, 2pm this instalment of the Star Wars saga sees original Sat 14 Sep, 8pm or catch up On Demand cast members Carrie Fisher, Mark Hamill and Sydney Opera House Harrison Ford reunited on the big-screen, with the Orchestra playing live to film. -

House Programme

13.11.2018 JC Cube Rare and Important Piano Collection HOUSE PROGRAMME House Rules 1 The performance will last for approximately 1 hour 20 minutes with one intermission. 2 Latecomers may only be admitted at a suitable break. 3 Recommended for ages 6 and above. 4 To avoid undue disturbance to the performers and other members of the audience, please switch off your mobile phones and any other sound and light emitting devices before the performance. Eating, drinking, audio or video recording and unauthorised photography are strictly prohibited in the auditorium. Thank you for your co-operation. All About Mozart Fortepiano | Geoffrey Lancaster Sonata in B-flat major KV 570 (Vienna 1789) | Allegro | Adagio | Allegretto Sonata in E-flat major KV 282 (Munich early-1775) | Adagio | Menuet I / Menuet II | Allegro – intermission – Rondo in A minor KV 511 (Vienna 1787) | Andante Sonata in B-flat major KV 333 (Linz 1783–4) | Allegro | Andante cantabile | Allegretto grazioso Learn more about the programme and the instruments in the programme notes written by Professor Lancaster: Photo by Kathy Wheatley-2 Geoffrey Lancaster Geoffrey Lancaster has been at the forefront of the historically-informed performance practice movement for 40 years. He was the first Australian to win a major international keyboard competition, receiving First Prize in the 23rd Festival van Vlaanderen International Fortepiano Competition, Brugge. He is Artistic Director with Ensemble of the Classic Era and a member of the Council of the Australian Youth Orchestra, and was Director of the Tasmanian Symphony Chamber Players, and Chief Conductor and Artistic Director of La Cetra Barockorchester Basel. -

C 1 Cembalomusik in Der Stadt Basel Bischofshof· Münstersaal

r Ein gutes Zusammenspiel ist entscheidend für gute Resultate. Fragen Sie uns! c 1 Cembalomusik in der Stadt Basel Bischofshof· Münstersaal Konzerte 2000/2001 30.11. Andrea Scherer Beratung und Ausführung 8.1. GeoffreyLancaster Kommunikations-Lösungen Visualisierungen 19.3. Thomas Ragossnig Grafik und Design 26.4. Bob van Asperen Satz, Lithos, Druck, Digital und Offset Datenbank-Lösungen Digitale Animationen und Video-Spots Versandlogistik Abonnemente und Vorverkauf: Musik Wyler Schneidergasse 24 , 40 51 Basel Telefon 061-261 90 25 Telefon 205 93 33 Fax 205 93 30 Linsenmann AG , Eulerstrasse 73 eMail [email protected] Postfach , 4009 Basel internet http ://www .linsenmann .ch Sehr geehrte Damen und Herren Liebe Musikfreunde Mit dem Generalprogramm 2000 /2001 möchten wir Ihnen die Konzerte der 11. Sai son vorstellen und hoffen, dass es uns auch in diesem Jahr gelungen ist, ein ab wechslungsreich es Programm mit vier inter essanten Konzertabenden zusammenzu stellen. Wir würd en uns freuen , Sie auch diese Saison als regelmässige Besuch er bei CIS begrüssen zu dürfen. Wir danken für die finanzielle Unterstützung - allen privaten Gönnern - Atelier Baumgartn er, Innenarchit ektur , Basel - Bree, Lederwaren, Basel - Haecky Drink AG, Reinach • Lott eriefondSj - Linsenmann AG, Druckerei, Basel -Olymp & Hades, Buchhand lung, Basel ~ Basel-Stadt \ - Schweizer Radio DRS 2, Studio Basel 1..\Kult ur __, - Stoffler, Orgeln und Pianos, Basel 1 und der Stadt Basel, die mit einem Beitrag der Abteilung Kultur des Lotteriefonds Basel-Stadt unterstü tzt. ATELIER lady top II. Damenhandtasche. Rindnappaleder . BAUMGARTNER INNENARCHITEKTUR B A E L s & WOHNBERATUNG MÖ BEL HEIMTEXTILIEN TEPPICHE LAMPEN OBJEKTPLANUNG WOHNA CCESSOIRES I BREE BASEL I RÜMELINSPLATZ 7 1 SPALENBERG 8 4051 BASEL TEL 061 2610843 FAX 261 08 63 4001 BASEL I TELEFON 061/261 II 26 1 Gunther Lambert-Collection bei Atelier Baumgartner Donnerstag, 30. -

Edith Cowan University

Edith Cowan University Western Australian Academy of Performing Arts Dr Geoffrey Lancaster – Publications Listing 2011 Lancaster, G 2011, 'Joseph Haydn Complete Keyboard Sonatas', Vol. 3, Booklet Notes, Tall Poppies, Sydney, Australia, pp. 1-34. ISBN 9399001002160. Lancaster, G 2011, Joseph Haydn Complete Keyboard Sonatas, Vol. 3, CD, TP 216, Tall Poppies, Sydney, Australia, pp. 64 min 37 sec. Lancaster, G 2011, 'Sonata quasi una fantasia: genre and performance in Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata', Henry Wood Lecture Recital, David Josefowitz Recital Hall, Royal Academy of Music, London, United Kingdom. Lancaster, G & Hart, D 2011, 'Williams and Haydn: Hidden Meanings', National Gallery of Australia Public Programs, Lecture Recital, James O Fairfax Theatre, National Gallery of Australia, Canberra, Australia. Lancaster, G & Pereira, D 2011, Complete Cello Sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven, Bundanon Trust, Riversdale, Nowra, Australia. Lancaster, G & Pereira, D 2011, Complete Cello Sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven, Embassy of the Republic of Finland, Yarralumla, Australia. Lancaster, G & Pereira, D 2011, Complete Cello Sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven, Woodworks Gallery, Bungendore, Australia. Lancaster, G & Pereira, D 2011, Complete Cello Sonatas by Ludwig van Beethoven, Wesley Music Centre, Forrest, Australia. Lancaster, G 2011, 'Keyboards', TV feature interview, The Collectors, Episode 19, ABC Television, Friday 9 September, Hobart, Australia, pp. 2 min 45 sec. Web. http://www.abc.net.au/tv/collectors/segments/s3314396.htm Lancaster, G 2011, 'Australia's precious ivories', Trust News Australia, vol. 3, no. 5, May, pp. 14-15. ISSN 1835-2316. Lancaster, G 2011, Sonata No. 60 in C, Hob. XVI:50 by Joseph Haydn, (World Premiere performance on Joseph Haydn's restored Longman and Broderip piano), The Cobbe Collection, National Trust, Hatchlands Park, Surrey, United Kingdom Lancaster, G 2011, Sonata No. -

31 July 2021

31 July 2021 12:01 AM Ludwig van Beethoven (1770 - 1827) Coriolan - overture Op.62 National Polish Radio Symphony Orchestra, Leonard Slatkin (conductor) PLPR 12:10 AM Wolfgang Amadeus Mozart (1756-1791) Rondo in A minor K.511 for piano Jean Muller (piano) LUERSL 12:21 AM Willem Kersters (1929-1998), Paul van Ostaijen (author) Hulde aan Paul (Op.79) Flemish Radio Choir, Vic Nees (conductor) BEVRT 12:30 AM Jean Barriere (1705-1747) Sonata No 10 in G major for 2 cellos Duo Fouquet (duo) CACBC 12:40 AM Witold Lutoslawski (1913-1994) Dance Preludes, for clarinet and piano Seraphin Maurice Lutz (clarinet), Eugen Burger-Yonov (piano) CZCR 12:50 AM Ermanno Wolf-Ferrari (1876-1948) Two orchestral intermezzi from "Il Gioielli della Madonna", Op 4 KBS Symphony Orchestra, Othmar Maga (conductor) KRKBS 01:00 AM Dmitry Shostakovich (1906-1975) Cello Sonata in D minor, Op 40 Arto Noras (cello), Konstantin Bogino (piano) HRHRT 01:22 AM Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) Sonata in G minor H.16.44 for piano Kristian Bezuidenhout (fortepiano) PLPR 01:33 AM Ludvig Norman (1831-1885) String Sextet in A major (Op.18) (1850) Stockholm String Sextet (sextet) SESR 02:01 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Vier letzte Lieder (Four Last Songs), AV 150 Andrea Rost (soprano), Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Riccardo Frizza (conductor) HUMTVA 02:22 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Final Scene of 'Der Rosenkavalier, op. 59' Andrea Rost (soprano), Agnes Molnar (soprano), Andrea Szanto (mezzo soprano), Hungarian Radio Symphony Orchestra, Riccardo Frizza (conductor) HUMTVA 02:35 AM Richard Strauss (1864-1949) Eine Alpensinfonie (An Alpine Symphony), op. -

The Concert Pianist Myth: Diversifying Undergraduate Piano Education in Australia

Edith Cowan University Research Online Theses : Honours Theses 2016 The Concert Pianist Myth: Diversifying undergraduate piano education in Australia Helen Mather Edith Cowan University Follow this and additional works at: https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons Part of the Higher Education Commons, and the Music Education Commons Recommended Citation Mather, H. (2016). The Concert Pianist Myth: Diversifying undergraduate piano education in Australia. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1496 This Thesis is posted at Research Online. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses_hons/1496 Edith Cowan University Copyright Warning You may print or download ONE copy of this document for the purpose of your own research or study. The University does not authorize you to copy, communicate or otherwise make available electronically to any other person any copyright material contained on this site. You are reminded of the following: Copyright owners are entitled to take legal action against persons who infringe their copyright. A reproduction of material that is protected by copyright may be a copyright infringement. Where the reproduction of such material is done without attribution of authorship, with false attribution of authorship or the authorship is treated in a derogatory manner, this may be a breach of the author’s moral rights contained in Part IX of the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Courts have the power to impose a wide range of civil and criminal sanctions for infringement of copyright, infringement of moral rights and other offences under the Copyright Act 1968 (Cth). Higher penalties may apply, and higher damages may be awarded, for offences and infringements involving the conversion of material into digital or electronic form. -

Geoffrey Lancaster in Recital MOZART on the FORTEPIANO

Geoffrey Lancaster in Recital MOZART ON THE FORTEPIANO MONDAY 2 SEPTEMBER CITY RECITAL HALL CONCERT DIARY SEPTEMBER Music from Swan Lake Wed 4 Sep, 7pm Thu 5 Sep, 7pm BEAUTY AND MAGIC Concourse Concert Hall, ROSSINI The Thieving Magpie: Overture Chatswood RAVEL Mother Goose: Suite TCHAIKOVSKY Swan Lake: Suite Umberto Clerici conductor Star Wars: The Force Awakens Sydney Symphony Presents Thu 12 Sep, 8pm in Concert Fri 13 Sep, 8pm Set 30 years after the defeat of the Empire, Sat 14 Sep, 2pm this instalment of the Star Wars saga sees original Sat 14 Sep, 8pm cast members Carrie Fisher, Mark Hamill and Sydney Opera House Harrison Ford reunited on the big-screen, with the Orchestra playing live to film. Classified M. PRESENTATION LICENSED BY PRESENTATION LICENSED BY DISNEY CONCERTS IN ASSOCIATION WITH 20TH CENTURY FOX, LUCASFILM, AND WARNER/CHAPPELL MUSIC. © 2019 & TM LUCASFILM LTD. ALL RIGHTS RESERVED © DISNEY Andreas Brantelid performs Meet the Music Elgar’s Cello Concerto Wed 18 Sep, 6.30pm Thursday Afternoon Symphony VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY’S MASTERWORKS Thu 19 Sep, 1.30pm VAUGHAN WILLIAMS Tea & Symphony* Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis Fri 20 Sep, 11am *ELGAR Cello Concerto Great Classics *ELGAR Enigma Variations Sat 21 Sep, 2pm Vladimir Ashkenazy conductor Sydney Opera House Andreas Brantelid cello Abercrombie & Kent Holst’s Planets Masters Series VLADIMIR ASHKENAZY'S MASTERWORKS Wed 25 Sep, 8pm MEDTNER Piano Concerto No.1 Fri 27 Sep, 8pm HOLST The Planets Sat 28 Sep, 8pm Vladimir Ashkenazy conductor Sydney Opera House Alexei Volodin piano Sydney Philharmonia Choirs OCTOBER The Four Seasons Meet the Music Thu 10 Oct, 6.30pm VIVALDI AND PIAZZOLLA Kaleidoscope PIAZZOLLA arr. -

FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT 2009–10 2 National Gallery of Australia Contents

FOUNDATION FOUNDATION FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT REPORT ANNUAL ANNUAL REPORT 2009–10 2009–10 © National Gallery of Australia, 2010 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher. Produced by the National Gallery of Australia, Canberra Design by dna creative, Sydney Printed by Special T, Sydney National Gallery of Australia GPO Box 1150 Canberra ACT 2601 nga.gov.au National Gallery of Australia Foundation Office Telephone (02) 6240 6454 The National Gallery of Australia is an Australian Government Agency FOUNDATION ANNUAL REPORT 2009–10 2 national gallery Of AUstraliA Contents Office Bearers 7 Objectives 7 Chairman’s Report 9 Contributors 18 Membership 31 financial statements 55 Bede Tungutalum Tiwi people born Australia 1952 Untitled 2009 synthetic polymer paint and natural earth pigments on cotton fabric 128.5 x 82 cm acquired with the Founding Donors 2010 Fund, 2010 fOUNDATiON ANNUAL REPORT 2009–10 3 4 national gallery Of AUstraliA William Barak Wurundjeri people Australia 1824–1903 Corroboree 1895 charcoal and natural earth pigments over pencil on linen image 60 x 76.4 cm support 60 x 76.4 cm acquired with the Founding Donors 2010 Fund, 2009 This is one of the largest and most impressive drawings produced by William Barak as a way of passing on his knowledge of traditional culture. in the top half of the composition, six Aboriginal men with traditional body painting perform a dance. The lower half of the drawing shows a group of people in elaborately decorated possum-skin cloaks sitting and clapping. -

The First Fleet Piano: Volume

THE FIRST FLEET PIANO A Musician’s View Volume One THE FIRST FLEET PIANO A Musician’s View Volume One GEOFFREY LANCASTER Published by ANU Press The Australian National University Acton ACT 2601, Australia Email: [email protected] This title is also available online at http://press.anu.edu.au National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry Creator: Lancaster, Geoffrey, 1954-, author. Title: The first fleet piano : a musician’s view. Volume 1 / Geoffrey Richard Lancaster. ISBN: 9781922144645 (paperback) 9781922144652 (ebook) Subjects: Piano--Australia--History. Music, Influence of--Australia--History. Music--Social aspects--Australia. Music, Influence of. Dewey Number: 786.20994 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying or otherwise, without the prior permission of the publisher. Cover based on an original design by Gosia Wlodarczak. Cover design by Nic Welbourn. Layout by ANU Press. Printed by Griffin Press. This edition © 2015 ANU Press. Contents List of Plates . xv Foreword . xxvii Acknowledgments . xxix Descriptive Conventions . xxxv The Term ‘Piano’ . xxxv Note Names . xxxviii Textual Conventions . xxxviii Online References . xxxviii Introduction . 1 Discovery . 1 Investigation . 11 Chapter 1 . 17 The First Piano to be Brought to Australia . 22 The Piano in London . 23 The First Pianos in London . 23 Samuel Crisp’s Piano, Made by Father Wood . 27 Fulke Greville Purchases Samuel Crisp’s Piano . 29 Rutgerus Plenius Copies Fulke Greville’s Piano . 31 William Mason’s Piano, Made by Friedrich Neubauer(?) . 33 Georg Friedrich Händel Plays a Piano . -

Annual Report 2019-20

AUSTRALIAN ACADEMY OF THE HUMANITIES ANNUAL REPORT 2019 2020 Championing a humanised future for Australia The Australian Academy of the Humanities is the peak national body for the humanities and one of the nation’s four Learned Academies. Established in 1969, we provide independent and authoritative advice, including to government, to ensure ethical, historical and cultural perspectives inform discussions regarding Australia’s future challenges and opportunities. We promote and recognise excellence in the humanities disciplines. The Academy plays a unique role in promoting international engagement and research collaboration and investing in the next generation of humanities researchers. Our elected Fellowship comprises 640 scholars, leaders and practitioners across the humanities disciplines of culture, history, languages, linguistics, philosophy, religion, archaeology and heritage. Australian Academy of the Humanities Annual Report 2019–20 This document is a true and accurate account of the activities and abridged fi nancial report of the Australian Academy of the Humanities for the fi nancial year 2019–20, in accordance with the reporting requirements of the Academy’s Royal Charter and By-laws, and for the conditions of grants made by the Australian Government under the Higher Education Support Act 2003 (Cth). Funding for the production of this report and a number of the activities described herein has been provided by the Australian Government through the Department of Education, Skills and Employment. The views expressed in this publication -

Performers Introduction

~ Introducing our performers 音樂家簡介 ~ ✪ All Souls’ Singing Group and Bible Study Group 全靈教會合唱團及中文查經班 Members 成員: (in alphabetical order 依姓氏排列 ) Brett Baglin, Hannah Hai, Young Lai 賴楊木, Justy Lai 賴奕廷, Lily Louey, Rebecca Lu 吕欣蓉, Debbie Mazlin, Jessica Nieh 聶惠珠, Batty Olsen, Jenny Tsai 蔡鶯梅, Serena Sun 孫映 雪, Roni Willis, Alvin Willis Sandra Minns – Accompanist 伴奏, Janelle Baglin – Conductor 指揮 All Souls' Singing Group is a bunch of people who like to sing, and especially to sing praises to God. They meet each Thursday at 5.30pm at All Souls' Anglican Church Chapman to rehearse the hymns and songs for their 9am Sunday service, where they attend and help lead the congregational singing. Reverend Janelle Baglin is the conductor and Mrs Sandra Minns the accompanist. It is their great honour and privilege to be part of the concert this afternoon, supporting this worthy cause. ✪ Jessica Tsou 鄒以靈 – Piano 鋼琴 Jessica Tsou is studying with Susanne Powell and Geoffrey Lancaster for a Master of Music degree majoring in Piano and Fortepiano performance. She has been awarded prizes in the national Eisteddfod and the School of Music's chamber music competition. ✪ Annette Liu 劉安蓁 – Cello 大提琴 Annette was born in Nov. 1995, and had lived in Africa, USA, Europe and Taiwan before. She travels a lot with her family and had just moved to Canberra in January 2012. Currently, Annette is a Year 11 student at the Narrabundah College. Annette started her music lessons at the age of 5, and started playing cello since six years old in Taipei. She attended the Helsinki Conservatory of Music when her family moved to Finland in Jan. -

4 HANDS GEOFFREY LANCASTER & ARNAN WIESEL Livefriday 1 August 2008, 7.30Pm Live Liveanu COLLEGE of ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES PROGRAM

SCHOOL OF MUSIC 4 HANDS GEOFFREY LANCASTER & ARNAN WIESEL LiveFriday 1 August 2008, 7.30pm Live LiveANU COLLEGE OF ARTS & SOCIAL SCIENCES PROGRAM Symphony no. 95 in c minor (1791) (arranged for piano 4-hands by Carl Czerny) Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) i) Allegro moderato ii) Andante iii) Menuetto - Trio iv) Finale: Vivace Fantasia in f minor op. 103 (D940) for piano 4-hands (1828) Franz Schubert (1797-1828) Allegro molto moderato – Largo - Allegro vivace - Allegro molto moderato INTERVAL Symphony no. 98 in B-flat major (1792) (arranged for piano 4-hands by Carl Czerny) Joseph Haydn (1732-1809) i) Adagio - Allegro ii) Adagio cantabile iii) Menuetto – Trio (Allegro) iv) Finale: Presto The terms ‘piano’, ‘pianoforte’, piano e forte’ and ‘fortepiano’ are used to describe a touch-sensitive keyboard instrument in which strings are struck by rebounding hammers. During the eighteenth century and the first half of the nineteenth century, all these terms were used interchangeably. Today, the term ‘fortepiano’ is used to describe pianos whose design originated prior to the early-nineteenth century, in order to distinguish them from later instruments. The fortepiano used in this recital is a precise copy by the American fortepiano maker Paul McNulty (Divisov, Czech Republic), of an instrument made in 1819 (opus 318) by the Viennese fortepiano maker Conrad Graf. The original piano is housed in Zamek Kozel (Goat Castle) near Pilsen, Czech Republic. The instruments of Graf represent one of the pinnacles in the development of the piano. The instrument has