Floating Palaces': the Transformation of Passenger Ships, C

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Being Lord Grantham: Aristocratic Brand Heritage and the Cunard Transatlantic Crossing

Being Lord Grantham: Aristocratic Brand Heritage and the Cunard Transatlantic Crossing 1 Highclere Castle as Downton Abbey (Photo by Gill Griffin) By Bradford Hudson During the early 1920s, the Earl of Grantham traveled from England to the United States. The British aristocrat would appear as a character witness for his American brother-in-law, who was a defendant in a trial related to the notorious Teapot Dome political scandal. Naturally he chose to travel aboard a British ship operated by the oldest and most prestigious transatlantic steamship company, the Cunard Line. Befitting his privileged status, Lord Grantham was accompanied by a valet from the extensive staff employed at his manor house, who would attend to any personal needs such as handling baggage or assistance with dressing. Aboard the great vessel, which resembled a fine hotel more than a ship, passengers were assigned to accommodations and dining facilities in one of three different classes of service. Ostensibly the level of luxury was determined solely by price, but the class system also reflected a subtle degree of social status. Guests in the upper classes dressed formally for dinner, with men wearing white or black tie and women wearing ball gowns. Those who had served in the military or diplomatic service sometimes wore their medals or other decorations. Passengers enjoyed elaborate menu items such as chateaubriand and oysters Rockefeller, served in formal style by waiters in traditional livery. The décor throughout the vessel resembled a private club in London or an English country manor house, with ubiquitous references to the British monarchy and empire. -

Impacts of Submarine Cables on the Marine Environment — a Literature Review —

Impacts of submarine cables on the marine environment — A literature review — September 2006 Funding agency: Federal Agency of Nature Conservation Contractor: Institute of Applied Ecology Ltd Alte Dorfstrasse 11 18184 Neu Broderstorf Phone: 038204 618-0 Fax: 038204 618-10 email: [email protected] Authors: Dr Karin Meißner Holger Schabelon (Qualified Geographer) Dr. Jochen Bellebaum Prof Holmer Sordyl Impacts of submarine cables on the marine environment - A literature review Institute of Applied Ecology Ltd Contents 1 Background and Objectives............................................................................... 1 2 Technical aspects of subsea cables.................................................................. 3 2.1 Fields of application for subsea cables............................................................. 3 2.1.1 Telecommunication cables.................................................................................... 3 2.1.2 Power transmission by cables............................................................................... 4 2.1.2.1 Direct current transmission ................................................................................... 4 2.1.2.2 Alternating current transmission............................................................................ 6 2.1.2.3 Cable types........................................................................................................... 6 2.1.3 Electrical heating of subsea flowlines (oil and gas pipelines) .............................. 10 2.2 Cable installation -

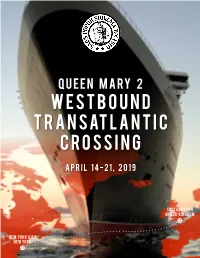

Westbound Transatlantic Crossing

Queen Mary 2 Westbound Transatlantic Crossing April 14-21, 2019 Southampton United Kingdom New York City New York Queen Mary 2 A flagship without compare. Luxury is in the details. Elegant suites and staterooms, sumptuous new restaurants and a re-imagined Grills experience reaffirm Cunard’s Queen Mary 2 as the best of the best. Departing from Southampton, England, seven heavenly nights on board is just what you need to ready yourself for the excitement of New York. When you wake up in the city that never sleeps, you will be fully rested from your luxurious week crossing the Atlantic. Cunard has been sailing from Southampton to New York and back since 1847, when they established the first regular service. Today only Queen Mary 2 regularly makes this journey and not only does she remain as glamorous and exciting as ever but an Atlantic Crossing also remains one of travel’s most iconic experiences. As the boundless ocean surrounds you, surrender to the rhythms of dining, discovery, mingling and relaxing. Elegant Entertainment Dine where the accommodation. abounds. mood takes you. Whether you plan to travel in Day and night, there are endless If anything sums up the freedom a sumptuous suite, or a room entertainment opportunities. of your voyage, it is the array of with a view, there is every type Dance lessons, Martini Mixology, places to eat - from healthy to of accommodation to make Insights presentations, deck hearty, from light bites to haute your voyage a truly remarkable games, theatre productions, cuisine. Just let your mood journey. cookery demonstrations, spa decide. -

Transatlantic Crossing in the 1920S and 30S – the Trajectories of the European Poetic and Scientific Avant-Garde in Brazil Ellen Spielmanna

Transatlantic crossing in the 1920s and 30s – the trajectories of the European poetic and scientific avant-garde in Brazil Ellen Spielmanna Abstract This article focuses on four paradigmatic cases of travelers. The central part concerns Dina Lévi-Strauss who gave the first course on modern ethnography in Brazil. She transfered the very latest: her projects include the founding of an ethnographic museum modeled on the “Musée de l`Homme”. Claude Lévi- Strauss and Fernand Braudel traveled to São Paulo as members of the French mission, which played an important role in the founding of the University of São Paulo. For political reasons Claude Lévi-Strauss’ contract at the University was not renewed in 1937. Blaise Cendrars was already a famous poet when he crossed the Atlantic in 1924. Fascism in Europe and World War II interrupted the careers of these four travelers as well as their interchanges with Brazil and their Brazilian friendships. But Brazilian experiences of Claude Lévi-Strauss and Braudel are crucial for their successful careers, after 1945. Keywords: Transatlantic crossing 20th Century, history of science, poetic and scientific avant-garde, University of São Paulo, Dina and Claude Lévi- Strauss, Fernand Braudel, Blaise Cendrars, Paulo Prado, Musée de l`Homme. Recebido em 21 de março de 2016 Aceito em 31 de março de 2016 a Professora e pesquisadora em Teoria literária e cultural da América Latina na Univ. de Tübingen, [email protected]. Gragoatá, Niterói, n. 41, p. 686-693, 2. sem. 2016 686 Transatlantic crossing in the 1920s and 30s During the 1920s and 1930s various members of the European avant-garde traveled to Brazil. -

Epilogue 1941—Present by BARBARA LA ROCCO

Epilogue 1941—Present By BARBARA LA ROCCO ABOUT A WEEK before A Maritime History of New York was re- leased the United States entered the Second World War. Between Pearl Harbor and VJ-Day, more than three million troops and over 63 million tons of supplies and materials shipped overseas through the Port. The Port of New York, really eleven ports in one, boasted a devel- oped shoreline of over 650 miles comprising the waterfronts of five boroughs of New York City and seven cities on the New Jersey side. The Port included 600 individual ship anchorages, some 1,800 docks, piers, and wharves of every conceivable size which gave access to over a thousand warehouses, and a complex system of car floats, lighters, rail and bridge networks. Over 575 tugboats worked the Port waters. Port operations employed some 25,000 longshoremen and an additional 400,000 other workers.* Ships of every conceivable type were needed for troop transport and supply carriers. On June 6, 1941, the U.S. Coast Guard seized 84 vessels of foreign registry in American ports under the Ship Requisition Act. To meet the demand for ships large numbers of mass-produced freight- ers and transports, called Liberty ships were constructed by a civilian workforce using pre-fabricated parts and the relatively new technique of welding. The Liberty ship, adapted by New York naval architects Gibbs & Cox from an old British tramp ship, was the largest civilian- 262 EPILOGUE 1941 - PRESENT 263 made war ship. The assembly-line production methods were later used to build 400 Victory ships (VC2)—the Liberty ship’s successor. -

Transparentes Museum / Transparent Museum

ANHANG 2 Dokumentation – Alle Wandtexte Aus der Breite der möglichen Fallbeispiele, die schlaglicht artig einzelne Aspekte der Zusammenarbeit verschiedener Abteilungen im Museum erhellen, in paradigmatische Fragen einführen und Anknüpfungspunkte zum Alltag der Besu - chenden darstellen können, wurden in neun, atmosphä risch sehr unterschiedlichen Themenräumen die im Folgenden vorgestellten Themen ausgewählt. Ihre Gestaltung in der Ersteinrichtung und im späteren Kulissenwechsel beruht auf einer experimentellen, ausstellungserprobten Kombination von Kunstwerken, erlebbarer Information und parti zipativer Didaktik. Dazu wurden Originale aus allen Sammlungsbereichen, darunter auch Trouvaillen aus dem Depot, epochen- und medienübergreifend miteinander in Bezie hung gesetzt, zum Teil auch um spezifische Leihgaben ergänzt. Zeitgenössische Positionen der Kunst, die sich ihrerseits mit der Institution Museum auseinandersetzen, kommentieren an einigen Stellen die Themen, sodass die Kriterien für deren Auswahl und Präsentationsweise wiede rum künstlerisch hinterfragt werden. Im Folgenden sind alle Wandtexte der jeweiligen Räume in der Reihenfolge ihres Auftretens beim Durchschreiten der Räume von E1 bis A7 (siehe Raumplan S. 45) zusammen gestellt. — ————————————————————————————————— EINFÜHRUNG E1: Willkommen [Auftakt mit historischem Besucherreglement von 1870, konfrontiert mit den zeitgenössischen Videoarbeiten von Florian Slotawa und Marina Abramović/ Ulay; Feedback-Box.] Sammeln, Bewahren, Forschen, Ausstellen, Vermitteln Zu den Kernaufgaben -

Marinemalerei Am Deutschen Schiffahrtsmuseum: Ein

www.ssoar.info Marinemalerei am Deutschen Schiffahrtsmuseum: ein Überblick über 30 Jahre Forschung Scholl, Lars U. Veröffentlichungsversion / Published Version Zeitschriftenartikel / journal article Empfohlene Zitierung / Suggested Citation: Scholl, L. U. (2002). Marinemalerei am Deutschen Schiffahrtsmuseum: ein Überblick über 30 Jahre Forschung. Deutsches Schiffahrtsarchiv, 25, 363-382. https://nbn-resolving.org/urn:nbn:de:0168-ssoar-54201-4 Nutzungsbedingungen: Terms of use: Dieser Text wird unter einer Deposit-Lizenz (Keine This document is made available under Deposit Licence (No Weiterverbreitung - keine Bearbeitung) zur Verfügung gestellt. Redistribution - no modifications). We grant a non-exclusive, non- Gewährt wird ein nicht exklusives, nicht übertragbares, transferable, individual and limited right to using this document. persönliches und beschränktes Recht auf Nutzung dieses This document is solely intended for your personal, non- Dokuments. Dieses Dokument ist ausschließlich für commercial use. All of the copies of this documents must retain den persönlichen, nicht-kommerziellen Gebrauch bestimmt. all copyright information and other information regarding legal Auf sämtlichen Kopien dieses Dokuments müssen alle protection. You are not allowed to alter this document in any Urheberrechtshinweise und sonstigen Hinweise auf gesetzlichen way, to copy it for public or commercial purposes, to exhibit the Schutz beibehalten werden. Sie dürfen dieses Dokument document in public, to perform, distribute or otherwise use the nicht in irgendeiner Weise abändern, noch dürfen Sie document in public. dieses Dokument für öffentliche oder kommerzielle Zwecke By using this particular document, you accept the above-stated vervielfältigen, öffentlich ausstellen, aufführen, vertreiben oder conditions of use. anderweitig nutzen. Mit der Verwendung dieses Dokuments erkennen Sie die Nutzungsbedingungen an. ̈ LARS U. -

Shipping Made in Hamburg

Shipping made in Hamburg The history of the Hapag-Lloyd AG THE HISTORY OF THE HAPAG-LLOYD AG Historical Context By the middle of the 19th Century the industrial revolution has caused the disap- pearance of many crafts in Europe, fewer and fewer workers are now required. In a first process of globalization transport links are developing at great speed. For the first time, railways are enabling even ordinary citizens to move their place of residen- ce, while the first steamships are being tested in overseas trades. A great wave of emigration to the United States is just starting. “Speak up! Why are you moving away?” asks the poet Ferdinand Freiligrath in the ballad “The emigrants” that became something of a hymn for a German national mo- vement. The answer is simple: Because they can no longer stand life at home. Until 1918, stress and political repression cause millions of Europeans, among them many Germans, especially, to make off for the New World to look for new opportunities, a new life. Germany is splintered into backward princedoms under absolute rule. Mass poverty prevails and the lower orders are emigrating in swarms. That suits the rulers only too well, since a ticket to America produces a solution to all social problems. Any troublemaker can be sent across the big pond. The residents of entire almshouses are collectively despatched on voyage. New York is soon complaining about hordes of German beggars. The dangers of emigration are just as unlimited as the hoped-for opportunities in the USA. Most of the emigrants are literally without any experience, have never left their place of birth, and before the paradise they dream of, comes a hell. -

Schreker's Die Gezeichneten

"A Superabundance of Music": Reflections on Vienna, Italy and German Opera, 1912-1918 Robert Blackburn I Romain Rolland's remark that in Germany there was too much music 1 has a particular resonance for the period just before and just after the First World War. It was an age of several different and parallel cultural impulses, with the new forces of Expressionism running alongside continuing fascination with the icons and imagery ofJugendstil and neo-rornanticism, the haunting conservative inwardness of Pfitzner's Palestrina cheek by jowl with rococo stylisation (Der Rosenkavalier and Ariadne auf Naxos) and the search for a re- animation of the commedia dell'arte (Ariadne again and Busoni's parodistic and often sinister Arlecchino, as well es Pierrot Lunaire and Debussy's Cello Sonata). The lure of new opera was paramount and there seemed to be no limit to the demand and market in Germany. Strauss's success with Salome after 1905 not only enable him to build a villa at Garmisch, but created a particular sound-world and atmosphere of sultriness, obsession and irrationalism which had a profound influence on the time. It was, as Strauss observed, "a symphony in the medium of drama, and is psychological like all music". 2 So, too, was Elektra, though this was received more coolly at the time by many. The perceptive Paul Bekker (aged 27 in 1909) was among the few to recognise it at once for the masterpiece it is.3 In 1911 it was far from clear that Del' Rosenkavalier would become Strauss' and Hofinannsthal's biggest commercial success, nor in 1916 that Ariadne all! Naxos would eventually be described as their most original collaboration.' 6 Revista Musica, Sao Paulo, v.5, n. -

SSHSA Ephemera Collections Drawer Company/Line Ship Date Examplesshsa Line

Brochure Inventory - SSHSA Ephemera Collections Drawer Company/Line Ship Date ExampleSSHSA line A1 Adelaide S.S. Co. Moonta Admiral, Azure Seas, Emerald Seas, A1 Admiral Cruises, Inc. Stardancer 1960-1992 Enotria, Illiria, San Giorgio, San Marco, Ausonia, Esperia, Bernina,Stelvio, Brennero, Barletta, Messsapia, Grimani,Abbazia, S.S. Campidoglio, Espresso Cagliari, Espresso A1 Adriatica Livorno, corriere del est,del sud,del ovest 1949-1985 A1 Afroessa Lines Paloma, Silver Paloma 1989-1990 Alberni Marine A1 Transportation Lady Rose 1982 A1 Airline: Alitalia Navarino 1981 Airline: American A1 Airlines (AA) Volendam, Fairsea, Ambassador, Adventurer 1974 Bahama Star, Emerald Seas, Flavia, Stweard, Skyward, Southward, Federico C, Carla C, Boheme, Italia, Angelina Lauro, Sea A1 Airline: Delta Venture, Mardi Gras 1974 Michelangelo, Raffaello, Andrea, Franca C, Illiria, Fiorita, Romanza, Regina Prima, Ausonia, San Marco, San Giorgio, Olympia, Messapia, Enotria, Enricco C, Dana Corona, A1 Airline: Pan Am Dana Sirena, Regina Magna, Andrea C 1974 A1 Alaska Cruises Glacier Queen, Yukon Star, Coquitlam 1957-1962 Aleutian, Alaska, Yukon, Northwestern, A1 Alaska Steamship Co. Victoria, Alameda 1930-1941 A1 Alaska Ferry Malaspina, Taku, Matanuska, Wickersham 1963-1989 Cavalier, Clipper, Corsair, Leader, Sentinel, Prospector, Birgitte, Hanne, Rikke, Susanne, Partner, Pegasus, Pilgrim, Pointer, Polaris, Patriot, Pennant, Pioneer, Planter, Puritan, Ranger, Roamer, Runner Acadia, Saint John, Kirsten, Elin Horn, Mette Skou, Sygna, A1 Alcoa Steamship Co. Ferncape, -

White Star Liners White Star Liners

White Star Liners White Star Liners This document, and more, is available for download from Martin's Marine Engineering Page - www.dieselduck.net White Star Liners Adriatic I (1872-99) Statistics Gross Tonnage - 3,888 tons Dimensions - 133.25 x 12.46m (437.2 x 40.9ft) Number of funnels - 1 Number of masts - 4 Construction - Iron Propulsion - Single screw Engines - Four-cylindered compound engines made by Maudslay, Sons & Field, London Service speed - 14 knots Builder - Harland & Wolff Launch date - 17 October 1871 Passenger accommodation - 166 1st class, 1,000 3rd class Details of Career The Adriatic was ordered by White Star in 1871 along with the Celtic, which was almost identical. It was launched on 17 October 1871. It made its maiden voyage on 11 April 1872 from Liverpool to New York, via Queenstown. In May of the same year it made a record westbound crossing, between Queenstown and Sandy Hook, which had been held by Cunard's Scotia since 1866. In October 1874 the Adriatic collided with Cunard's Parthia. Both ships were leaving New York harbour and steaming parallel when they were drawn together. The damage to both ships, however, was superficial. The following year, in March 1875, it rammed and sank the US schooner Columbus off New York during heavy fog. In December it hit and sank a sailing schooner in St. George's Channel. The ship was later identified as the Harvest Queen, as it was the only ship unaccounted for. The misfortune of the Adriatic continued when, on 19 July 1878, it hit the brigantine G.A. -

SS City of Paris

SS City of Paris SS Belgenland SS Arizona SS Servia SS City of Rome Launched 1865 e Inman Line Launched 1878 e Red Star Line Launched 1879 e Guion Line Launched 1881 e Cunard Line Launched 1882 e Anchor Line For most of its life, The SS Servia the SS City of Paris This ship spent The ships of the was the first large The SS City of Rome was a passenger most of her life Guion Line were ocean liner to be was built to be the with the Red Star known mostly as United Kingdom largest and fastest United Kingdom ship. At her fastest, United Kingdom U.S. & Belgium United Kingdom built of steel in- she could make it Line working as a immigrant ships. stead of iron, and the first Cunard ship of her time, but the builders from Queenstown, Ireland to New passenger ship between Antwerp At the time of her launch, the SS Line ship with any electric lighting. used iron instead of steel for her hull, York City in 9 days. In 1884, she was and New York City. She was sold Arizona was one of the fastest ships At the time of its launch, her public making her too heavy for fast speeds. sold to the American Fur Company to the American Line in 1895 and on the Atlantic, but took so much rooms were the most luxurious of However, her First Class quarters and converted to a cargo ship. The worked for 8 more years as a 3rd coal and was so uncomfortable that any ocean-going ship.