Participation of Marginalized Groups in REDD+ Pilot Project, Dolakha District, Nepal

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

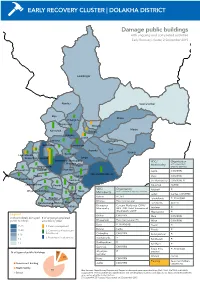

Early Recovery Cluster | Dolakha District

EARLY RECOVERY CLUSTER | DOLAKHA DISTRICT Damage public buildings with ongoing and completed activities Early Recovery cluster, 2 September 2015 Lamabagar Alambu Gaurishankar Bigu Khare Chilangkha Khopachagu Worang Marbu Kalinchok Bulung Babare Laduk Lapilang Changkhu Sundrawati Lamidanda Jhyanku Suri Syama Boch Sunkhani Lakuridanda Suspa Kshyamawati Jungu Bhimeswor Municipality VDC/ Organisation Chhetrapa Municipality with completed/ Magapauwa Kabre ongoing activities Bhusaphedi Katakuti Namdru Japhe CWV/RRN JIRI MUNICIPALITY Phasku Mirge Jhule CWV/RRN Dodhapokhari Gairimudi Jiri Municipality CWV/RRN, PI Bhirkot Sailungeshwar Pawati Kalinchok ACTED VDC/ Organisation Katakuti PI Ghyangsukathokar Jhule Hawa Municipality with completed/ongoing activities Japhe Laduk Caritas, CWV/RRN Babare ACTED Bhedpu Chyama Lakuridanda PI, RI/ANSAB Bhedpu Plan International Dandakharka Melung Malu Lamidanda ACTED Shahare Bhimeswor Concern Worldwide (CWV)/ Municipality RRN. IOM, Relief International Lapilang PI (RI)/ANSAB, UNDP Magapauwa PI Legend Bhirkot CWV/RRN Malu CWV/RRN # of completely damaged # of ongoing/completed public buildings activities by pillar Bhusaphedi Plan International (PI) Mirge CWV/RRN Boch PI, RI/ANSAB 21-28 1. Debris management Pawati PI Bulung Carita 11-20 2. Community infrastructure Phasku PI & livelihood 6-10 Chilangkha CWV/RRN Sailungeshwar PI 3. Restoration local services 3-5 Dandakharka PI Sundrawati PI Dodhapokhari PI 4% 1-2 Sunkhani PI Gairimudi CWV/RRN 12% Suspa Kshy- PI, RI/ANSAB Ghyangsu- PI amawati % of type of public buildngs 7% kathokar 14% Worang Caritas Hawa CWV/RRN Government building Planning Save the Children, Japhe CWV/RRN Government building Health facility UNDP/UNV Health facility School 79% Map Sources: Nepal Survey Department, Report on damaged government buildings, DoE, MoH, MoFALD and MoUD, 84% School August 2015. -

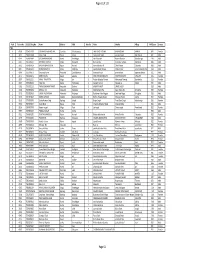

VBST Short List

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

District Profile - Dolakha (As of 10 May 2017) HRRP

District Profile - Dolakha (as of 10 May 2017) HRRP This district profile outlines the current activities by partner organisations (POs) in post-earthquake recovery and reconstruction. It is based on 4W and secondary data collected from POs on their recent activities pertaining to housing sector. Further, it captures a wide range of planned, ongoing and completed activities within the HRRP framework. For additional information, please refer to the HRRP dashboard. FACTS AND FIGURES Population: 280,8741 48 VDCs and 2 municipalities Damage Status - Private Structures Type of housing walls Dolakha National Mud-bonded bricks/stone 92% 41% Cement-bonded bricks/stone 5% 29% Damage Grade (3-5) 56,293 Other 3% 30% Damage Grade (1-2) 4,346 % of households who own 94% 85% Total 60,6392 their housing unit (Census 2011)1 NEWS & UPDATES 1. NRA Dolakha is planning to do survey of buildings which were missed out or where people were not convinced by the previous survey. NRA is planning to use the same DLPIU Engineers for the survey. The start date is yet to be finalized because of the election. 2. Bhimeshwor Municipality ward 1 (new) Bosimpa has been identified as one major village to resettle and they are planning to resettle 82 HH to Panipokhari. This is also taken as major pilot resettlement project in Dolakha. HRRP Dolakha HRRP © PARTNERS SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS3 Partner Organisation Implementing Partner(s) BC PLAN 2,338 1,645 CA CEEPAARD,HURADEC SHORT TRAINING CARITAS - L POURAKHI VOCATIONAL TRAINING 599 5,398 CARITAS-N (Targets Achieved) CW RRN -

Dolakhatopographic Map - June 2015

fh N e p a l DolakhaTopographic Map - June 2015 3 000m. 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 000m. N N . 91 E 92 93 85°55'9E4 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 86°0E2 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 8160°5'E 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1868°10'E 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 2686°15'E 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 86°20'E35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 86°254'E3 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 86°5301'E 52 53 54 55 56 E. m m 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 1 1 1 1 3 3 17 17 17 17 N ' 0 1 ° N 8 5 ' 2 16 160 16 4 16 0 1 0 ° 8 2 15 15 15 15 5 2 0 T 14 0 14 14 50 14 a 00 m b 13 13 a 13 13 0 K 80 4 4 6 o 0 s 0 0 12 12 00 20 12 12 i 44 4 4 4 0 0 0 11 0 11 11 Lapchegaun 2 11 ! 4 0 000 0 31 5 31 4 i 10 4 10 10 4800 0 10 s 0 0 4 4 0 5 8 6 o 0 4 0 K 0 09 09 60 0 09 09 4 60 4 a 5000 b 08 5 m 08 6 08 08 0 0 0 a 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 0 4 5 T 0 5 0 5 N ' 0 4 5 5 0 07° 07 8 0 07 07 N 2 ' 5 0 ° Gumba 0 8 6 2 3800 5 06 06 06 06 0 0 8 5 4 6 Thasing ! 0 05 0 05 5 05 05 0 0 5 0 40 0 0 4 4 0 0 C H I N A 6 0 4 2 0 5 0 0 0 00 0 8 5 0 0 4 04 0 5 54 04 0 04 3 04 0 4800 u 0 0 4 h 6 0 600 5 0 C 4 0 4 0 2 0 4 0 5 0 00 r 03 0 5 0 6 03 0 03 0 0a3 0 0 6 6 5 5 h 0 0 Thangchhemu s 2 0 ! g 6 5 R o n 8 4 0 80 0 02 0 02 02 02 0 0 6 4 4 4 5 0 0 i 2 01 0 0 01 44 01 0 01 h 0 f s 5 ! 6 0 4 o 0 31 2 Lomnang 31 0 ! 00 0 K 00 00 5 00 4 0 e 0 0 f 0 600 ! 0 0 6 3 t 0 8 2 4 4 5 4 5 5 0 40 0 56 0 0 0 o 0 0 0 0 5 99 Tarkeghang 0 0 56 400 99 0 99 Lumnang 99 3 3 0 f 6 h 0 ! 2 3 0 0 4 ! 0 0 4 5 f 0 B 4 0 0 f 6 ! 4 Pangbuk 0 3 ! ! 0 0 6 0 0 5200 4 Pangbuk 98 0 98 N 0 98 98 ° 3 0 Goth 8 ! 2 N ° 5 3200 8 2 2 0 97 3 5 0 97 60 3 6 97 97 0 2 38 0 0 3 0 0 0 8 0 0 0 f 4 96 00 50 96 ! 0 Tatopani 18 96 0 -

Global Initiative on Out-Of-School Children

ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Government of Nepal Ministry of Education, Singh Darbar Kathmandu, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 4200381 www.moe.gov.np United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Institute for Statistics P.O. Box 6128, Succursale Centre-Ville Montreal Quebec H3C 3J7 Canada Telephone: +1 514 343 6880 Email: [email protected] www.uis.unesco.org United Nations Children´s Fund Nepal Country Office United Nations House Harihar Bhawan, Pulchowk Lalitpur, Nepal Telephone: +977 1 5523200 www.unicef.org.np All rights reserved © United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) 2016 Cover photo: © UNICEF Nepal/2016/ NShrestha Suggested citation: Ministry of Education, United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO), Global Initiative on Out of School Children – Nepal Country Study, July 2016, UNICEF, Kathmandu, Nepal, 2016. ALL CHILDREN IN SCHOOL Global Initiative on Out-of-School Children © UNICEF Nepal/2016/NShrestha NEPAL COUNTRY STUDY JULY 2016 Tel.: Government of Nepal MINISTRY OF EDUCATION Singha Durbar Ref. No.: Kathmandu, Nepal Foreword Nepal has made significant progress in achieving good results in school enrolment by having more children in school over the past decade, in spite of the unstable situation in the country. However, there are still many challenges related to equity when the net enrolment data are disaggregated at the district and school level, which are crucial and cannot be generalized. As per Flash Monitoring Report 2014- 15, the net enrolment rate for girls is high in primary school at 93.6%, it is 59.5% in lower secondary school, 42.5% in secondary school and only 8.1% in higher secondary school, which show that fewer girls complete the full cycle of education. -

Section 3 Zoning

Section 3 Zoning Section 3: Zoning Table of Contents 1. OBJECTIVE .................................................................................................................................... 1 2. TRIALS AND ERRORS OF ZONING EXERCISE CONDUCTED UNDER SRCAMP ............. 1 3. FIRST ZONING EXERCISE .......................................................................................................... 1 4. THIRD ZONING EXERCISE ........................................................................................................ 9 4.1 Methods Applied for the Third Zoning .................................................................................. 11 4.2 Zoning of Agriculture Lands .................................................................................................. 12 4.3 Zoning for the Identification of Potential Production Pockets ............................................... 23 5. COMMERCIALIZATION POTENTIALS ALONG THE DIFFERENT ROUTES WITHIN THE STUDY AREA ...................................................................................................................................... 35 i The Project for the Master Plan Study on High Value Agriculture Extension and Promotion in Sindhuli Road Corridor in Nepal Data Book 1. Objective Agro-ecological condition of the study area is quite diverse and productive use of agricultural lands requires adoption of strategies compatible with their intricate topography and slope. Selection of high value commodities for promotion of agricultural commercialization -

Cg";"Lr–1 S.N. Application ID User ID Roll No बिज्ञापन नं. तह पद उम्मेदव

cg";"lr–1 S.N. Application ID User ID Roll No बिज्ञापन नं. तह पद उ륍मेदवारको नाम लऱगं जꅍम लमतत सम्륍मलऱत हुन चाहेको समूह थायी न. पा. / गा.वव.स-थायी वडा नं, थायी म्ज쥍ऱा नागररकता नं. 1 85994 478714 24001 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager ANIL NIROULA Male 2040/01/09 खलु ा Biratnagar-5, Morang 43588 2 86579 686245 24002 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager ARJUN SHRESTHA Male 2037/08/01 खलु ा Bhadrapur-13, Jhapa 1180852 3 28467 441223 24003 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager ARUN DHUNGANA Male 2041/12/17 खलु ा Myanglung-2, Tehrathum 35754 4 34508 558226 24004 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager BALDEV THAPA Male 2036/03/24 खलु ा Sikre-7, Nuwakot 51203 5 69018 913342 24005 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager BHAKTA BAHADUR KHATRI CHATRI Male 2038/12/25 खलु ा PUTALI BAZAR-14, Syangja 49247 6 89502 290954 24006 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager BIKAS GIRI Male 2034/03/15 खलु ा Kathmandu-31, Kathmandu 586/4042 7 6664 100010 24007 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager DINESH GAUTAM Male 2036/03/11 खलु ा Nepalgunj-12, Banke 839 8 62381 808488 24008 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager DINESH OJHA Male 2036/12/15 खलु ा Biratnagar Metropolitan-12, Morang 1175483 9 89472 462485 24009 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager GAGAN SINGH GHIMIRE Male 2033/04/26 खलु ा MAIDAN-3, Arghakhanchi 11944/3559 10 89538 799203 24010 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager GANESH KHATRI Male 2028/07/25 खलु ा TOKHA-5, Kathmandu 4/2161 11 32901 614933 24011 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager KHIL RAJ BHATTARAI Male 2039/08/08 खलु ा Bhaktipur-6, Sarlahi 83242429 12 70620 325027 24012 24/2075/76 9 Senior Manager KRISHNA ADHIKARI Male 2038/03/23 खलु ा walling-10, -

Nepal Earthquake Evaluation

PLAN INTERNATIONAL DEC-FUNDED RESPONSE TO THE NEPAL EARTHQUAKES, 2015 INDEPENDENT EVALUATION FINAL REPORT 2018 Environmental Partnerships for Resilient Communities TABLE OF CONTENTS ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS 4 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS 5 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY 6 1. INTRODUCTION 10 1.1 Background and Context 10 1.2 Plan’s Emergency and Recovery Response 11 1.3 Project Implementation 12 1.4 This Evaluation 13 1.5 Snapshot of Key Findings and Some Concerns 13 2. STRUCTURE OF THIS REPORT 14 3. METHODOLOGY 15 4. APPROACH 16 4.1 Team Composition 16 4.2 Tools 16 4.3 Schedule 17 5. DATA ANALYSIS ALIGNED WITH SELECTED OECD-DAC CRITERIA AND CORE HUMANITARIAN STANDARDS 18 5.1 Relevance 18 5.2 Timeliness 19 5.3 Effectiveness 19 5.4 Efficiency 20 5.5 Impact 21 5.6 Sustainability 22 5.7 Core Humanitarian Standards 23 6. MAIN FINDINGS 26 6.1 Overview 26 6.2 General Observations 34 6.3 Livelihoods 38 6.4 Water, Sanitation and Hygiene 41 6.5 Domestic Energy 47 6.6 Shelter 49 6.7 Disaster Risk Preparedness 50 6.8 Project Management and Monitoring 51 7. LESSONS TO CONSIDER 52 8. RECOMMENDATIONS 53 8.1 General 53 8.2 Protection 55 8.3 WASH 55 2 8.4 Livelihoods 57 8.5 Livestock Management 58 9. CONCLUSIONS 59 BIBLIOGRAPHY 60 ANNEXES Annex I Terms of Reference for the Evaluation Annex II Schedule for this Evaluation Annex III Evaluation Team Profile Annex IV People Consulted as part of this Evaluation Annex V Household Survey Questionnaire Annex VI Institutional Questionnaire Annex VII Guiding Questions for Focus Group Discussions 3 ACRONYMS AND ABBREVIATIONS DEC Disasters -

Result on VBST 4Th Round

Reg. S. No. Name Gender Citizenship No. Age District VDC Father Name Mother Name Trainee ID Number 1 11689 AAITI MAYA TAMANG Female 64172 34 Nuwakot Bungtang NURBU TASHI TAMANG SIKUCHA TAMANG 153567 2 15908 AAKANTA SUCHIKAR Male 361039/1102 21 Nawalparasi Parsauni MUKUNDA SUCHIRAR GOMATI SUCHIKAR 154712 3 16153 AAKASH SHRESTHA Male 27-01-72-07907 16 Kathmandu Manmaiju SAMBAK SHRESTHA ASTA MAYA BYANJANKAR 142501 4 14797 AAKASH SHRESTHA Male 24-0-69-00743 22 SindhupalchowkBhotechaur BISHNU SHRESTHA BINA SHRESTHA 144451 Reg. S. No. Name Gender Citizenship No. Age District VDC Father Name Mother Name Trainee ID Number 5 12962 AAKRITI MUKTAN Female 30/01/72/07626 18 KavrepalanchokFoksingtar TIR BAHADUR MUKTAN DHANMAYA MUKTAN 152753 6 13571 AAMME MAYA TAMANG Female 1180/299 36 Rasuwa Dandagoun MANGALE TAMANG SUKUMAYA TAMANG 139662 7 29704 AASHA KAHREL Female 261/29218 24 Dhading Gajuri DHIRENDRA KHAREL NIRMALA KHAREL 143570 8 67530 AASHA MAYA TAMANG Female 3003/36 19 Nuwakot Manakamana NIL BAHADUR TAMANG MAITI TAMANG 154841 9 42357 AASHA RAM TAMANG Male 28-01-71-02278 20 Lalitpur Devichour RAM BDR TAMANG SHUKUMAYA TAMANG 150221 10 21178 AASHIAK BAIDHYA Female 19-02-70-00744 18 Sarlahi Pattharkot SHIVA KUMAR BAIDHYA INDIRA KUMARI BAIDHYA 144659 11 23444 AASHIS LAMA Male 103774 35 KavrepalanchokPokhariNarayansthanKHADGA BAHADUR LAMA MAYA LAMA 142298 12 42684 AASHIS MOTE Male 06-01-71-06634 22 Sunsari MahendranagarGOPAL MOTE SHANTI DEBI MOTE 154078 13 18611 Aashish Bindukar Male 27-01-72-08084 17 Kathmandu Ananda Bindukar Rita Bindukar 142070 14 29465 AASHISH MAHARJAN Male 28-01-72-02824 17 Lalitpur Lalitpur U.M.N.P.AASA RAM MAHARJAN CHIRI MAI MAHARJAN 148724 15 19229 AASHISH PARIYAR Male 28-01-066-01162 24 Lalitpur Lalitpur U.M.N.P.BIKRAM PARIYAR SABITRI PARIYAR 147639 16 42611 AASHISH SHRESTHA Male 273046/40 20 Kathmandu Satungal BISHNU BHAKTA SHRESTHA SAPANA SHRESTHA 154004 17 29443 AASHMAN GOLE Male 52961174 30 Sarlahi Lalbandi BIR BAHADUR GOLE FULMAYA GOLE 146467 18 15669 AASISH KHAKDA Male 439022/256 20 Tanahun SAMSER BD. -

Resource Analysis of Chyuri (Aesandra Butyracea) in Nepal

Micro Enterprise Development Programme - MEDEP GON/MOICS/UNDP – NEP/08/006 Resource Analysis of Chyuri (Aesandra butyracea) in Nepal Micro-Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP-NEP 08/006) Kathmandu, Nepal June 2010 Copyright © 2010 Micro-Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP-NEP 08/006) UNDP/Ministry of Industry, Government of Nepal Bakhundole, Lalitpur PO Box 815 Kathmandu, Nepal Tel +975-2-322900 Fax +975-2-322649 Website: www.medep.org.np Author Surendra Raj Joshi Reproduction This publication may not be reproduced in whole or in part in any form without permission from the copyright holder, except for educational or nonprofit purposes, provided an acknowledgment of the source is made and a copy provided to Micro-enterprise Department Programme. Disclaimer The views and opinions expressed in this document are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect those of MEDEP or the Ministry of Industry. The information contained in this publication has been derived from sources believed to be reliable. However, no representation or warranty is given in respect of its accuracy, completeness or reliability. MEDEP does not accept liability for any consequences/loss due to use of the content of this publication. Note on the use of the terms: Aesandra butyracea is known by various names; Indian butter tree, Nepal butter tree, butter tree. In Nepali soe say Chyuri ad others say Chiuri. ACKNOWLEDGMENTS This study was carried out within the overall framework of the Micro-Enterprise Development Programme (MEDEP-NEP 08/006) with an objective to identify the geographical and ecological coverage of Chyuri tree, and to estimate the resource potentiality for establishment of enterprises.