Nepal Earthquake Evaluation

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

List of Annex

List of Annex Annex 1.1 List of Officers and Stakeholders Met (1st Stage) Annex 1.2 Field Trip Report Annex 1.3 Key Literatures and Reports Reviewed Annex 1.4 List of Officers and Stakeholders Met (2nd Stage) Annex 1.5 Questionnaire for Household Survey Annex 1.6 Traders Survey Questionnaire Annex 1.7 Report of Workshops Annex 2.1 Organization Chart of MOAC Annex 2.2 Major Functions /Roles of Different Organizational Unit of DOA Annex 2.3 Import of Selected Agricultural and Related Commodities from India and Countries other than India Annex 2.4 Export of Selected Agricultural and Related Commodities to India and Countries other than India Annex 2.5 Agriculture Markets Network in Nepal Annex 2.6 Map of Nepal Showing Agriculture Markets Network in Nepal Annex 2.7 Organization Chart of MoLD Annex 3.1 Map of Nepal Showing Survey Districts Annex 3.2 Map of Kavrepalanchok District Showing the Proposed VDCs for Survey Annex 3.3 Map of Sindhuli District Showing the Proposed VDCs for Survey Annex 3.4 Map of Mahottari District Showing the Proposed VDCs for Survey Annex 3.5 Map of Ramechhap District Showing the Proposed VDCs for Survey Annex 3.6 Map of Dolakha District Showing the Proposed VDCs for Survey Annex 3.7 Summary of Periodic District Development Plans Annex 3.8 Organizational Structure of DDC Annex 3.9 Organizational Structure of District Technical Office Annex 3.10 Key Agriculture Sector INGOs /NGOs /COs Working in the Survey Districts Annex 3.11 Annual Programs and Projects Implemented by DADO in FY 2008/09 Annex 3.12 Proportions of Cropped Area under Different Crops, 2007/08 Annex 3.13 Lists of VDCs by Potentiality Commodities Annex 5.1 Profile of Selected Markets Annex 1.1 Annex 1.1 List of Officers & Stakeholders Met (1st Stage) Date Name Organization Designation Venue Mar. -

Participation of Marginalized Groups in REDD+ Pilot Project, Dolakha District, Nepal

Participation of Marginalized Groups in REDD+ Pilot Project, Dolakha District, Nepal Anjana Mulepati Thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of Philosophy in Culture, Environment and Sustainability Centre for Development and the Environment University of Oslo Blindern, Norway May 2012 ii Acknowledgement First of all, I would like to thank Professor Desmond McNeill of Centre for Development and the Environment at University of Oslo for his academic guidance during my thesis work. Also, I am deeply indebted to Mr. Eak B. Rana Magar, Project Coordinator of REDD at International Centre for Integrated Mountain Development (ICIMOD), Mr. Keshav Prasad Khanal, Senior Officer at REDD-Cell, Ministry of Forest and Soil Conservation, Nepal, Mr. Nabaraj Dahal, Program Manager at Federation of Community Forest User Groups, Nepal and Mr. Rijan Tamrakar, Forestry Officer at Asia Network for Sustainable Agriculture and Bio-resources for their valuable inputs and information during my research work.. I am also grateful to all the staffs and my friends of Centre for Development and the Environment (SUM), University of Oslo and also to all the respondents of my survey from the ministries, department to the members of community forest users groups at Dolakha District. Here, I would like to take a chance to express my gratitude towards Ms. Pasang Dolma Sherpa, National Coordinator at Nepal Federation of Indigenous Nationalities (NEFIN), Ms. Geeta Bohara, General Secretary at Himalayan Grassroots Women's Natural Resource Management Association (HIMAWANTI) and Mr. Sunil Pariyar, Chairperson at Dalit Alliance for Natural Resources of Nepal (DANAR ) for their information during my thesis work. -

Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal

SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics SMALL AREA ESTIMATION OF FOOD INSECURITY AND UNDERNUTRITION IN NEPAL GOVERNMENT OF NEPAL National Planning Commission Secretariat Central Bureau of Statistics Acknowledgements The completion of both this and the earlier feasibility report follows extensive consultation with the National Planning Commission, Central Bureau of Statistics (CBS), World Food Programme (WFP), UNICEF, World Bank, and New ERA, together with members of the Statistics and Evidence for Policy, Planning and Results (SEPPR) working group from the International Development Partners Group (IDPG) and made up of people from Asian Development Bank (ADB), Department for International Development (DFID), United Nations Development Programme (UNDP), UNICEF and United States Agency for International Development (USAID), WFP, and the World Bank. WFP, UNICEF and the World Bank commissioned this research. The statistical analysis has been undertaken by Professor Stephen Haslett, Systemetrics Research Associates and Institute of Fundamental Sciences, Massey University, New Zealand and Associate Prof Geoffrey Jones, Dr. Maris Isidro and Alison Sefton of the Institute of Fundamental Sciences - Statistics, Massey University, New Zealand. We gratefully acknowledge the considerable assistance provided at all stages by the Central Bureau of Statistics. Special thanks to Bikash Bista, Rudra Suwal, Dilli Raj Joshi, Devendra Karanjit, Bed Dhakal, Lok Khatri and Pushpa Raj Paudel. See Appendix E for the full list of people consulted. First published: December 2014 Design and processed by: Print Communication, 4241355 ISBN: 978-9937-3000-976 Suggested citation: Haslett, S., Jones, G., Isidro, M., and Sefton, A. (2014) Small Area Estimation of Food Insecurity and Undernutrition in Nepal, Central Bureau of Statistics, National Planning Commissions Secretariat, World Food Programme, UNICEF and World Bank, Kathmandu, Nepal, December 2014. -

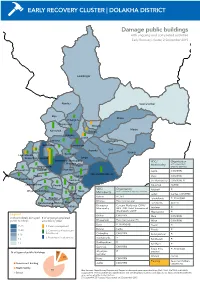

Early Recovery Cluster | Dolakha District

EARLY RECOVERY CLUSTER | DOLAKHA DISTRICT Damage public buildings with ongoing and completed activities Early Recovery cluster, 2 September 2015 Lamabagar Alambu Gaurishankar Bigu Khare Chilangkha Khopachagu Worang Marbu Kalinchok Bulung Babare Laduk Lapilang Changkhu Sundrawati Lamidanda Jhyanku Suri Syama Boch Sunkhani Lakuridanda Suspa Kshyamawati Jungu Bhimeswor Municipality VDC/ Organisation Chhetrapa Municipality with completed/ Magapauwa Kabre ongoing activities Bhusaphedi Katakuti Namdru Japhe CWV/RRN JIRI MUNICIPALITY Phasku Mirge Jhule CWV/RRN Dodhapokhari Gairimudi Jiri Municipality CWV/RRN, PI Bhirkot Sailungeshwar Pawati Kalinchok ACTED VDC/ Organisation Katakuti PI Ghyangsukathokar Jhule Hawa Municipality with completed/ongoing activities Japhe Laduk Caritas, CWV/RRN Babare ACTED Bhedpu Chyama Lakuridanda PI, RI/ANSAB Bhedpu Plan International Dandakharka Melung Malu Lamidanda ACTED Shahare Bhimeswor Concern Worldwide (CWV)/ Municipality RRN. IOM, Relief International Lapilang PI (RI)/ANSAB, UNDP Magapauwa PI Legend Bhirkot CWV/RRN Malu CWV/RRN # of completely damaged # of ongoing/completed public buildings activities by pillar Bhusaphedi Plan International (PI) Mirge CWV/RRN Boch PI, RI/ANSAB 21-28 1. Debris management Pawati PI Bulung Carita 11-20 2. Community infrastructure Phasku PI & livelihood 6-10 Chilangkha CWV/RRN Sailungeshwar PI 3. Restoration local services 3-5 Dandakharka PI Sundrawati PI Dodhapokhari PI 4% 1-2 Sunkhani PI Gairimudi CWV/RRN 12% Suspa Kshy- PI, RI/ANSAB Ghyangsu- PI amawati % of type of public buildngs 7% kathokar 14% Worang Caritas Hawa CWV/RRN Government building Planning Save the Children, Japhe CWV/RRN Government building Health facility UNDP/UNV Health facility School 79% Map Sources: Nepal Survey Department, Report on damaged government buildings, DoE, MoH, MoFALD and MoUD, 84% School August 2015. -

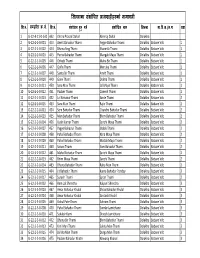

VBST Short List

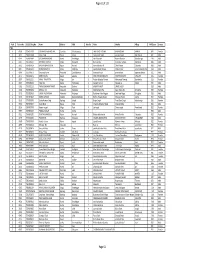

1 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10002 2632 SUMAN BHATTARAI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. KEDAR PRASAD BHATTARAI 136880 10003 28733 KABIN PRAJAPATI BHAKTAPUR BHAKTAPUR N.P. SITA RAM PRAJAPATI 136882 10008 271060/7240/5583 SUDESH MANANDHAR KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. SHREE KRISHNA MANANDHAR 136890 10011 9135 SAMERRR NAKARMI KATHMANDU KATHMANDU M.N.P. BASANTA KUMAR NAKARMI 136943 10014 407/11592 NANI MAYA BASNET DOLAKHA BHIMESWOR N.P. SHREE YAGA BAHADUR BASNET136951 10015 62032/450 USHA ADHIJARI KAVRE PANCHKHAL BHOLA NATH ADHIKARI 136952 10017 411001/71853 MANASH THAPA GULMI TAMGHAS KASHER BAHADUR THAPA 136954 10018 44874 RAJ KUMAR LAMICHHANE PARBAT TILAHAR KRISHNA BAHADUR LAMICHHANE136957 10021 711034/173 KESHAB RAJ BHATTA BAJHANG BANJH JANAK LAL BHATTA 136964 10023 1581 MANDEEP SHRESTHA SIRAHA SIRAHA N.P. KUMAR MAN SHRESTHA 136969 2 आिेदकको दर्ा ा न륍बर नागररकर्ा न륍बर नाम थायी जि쥍ला गा.वि.स. बािुको नाम ईभेꅍट ID 10024 283027/3 SHREE KRISHNA GHARTI LALITPUR GODAWARI DURGA BAHADUR GHARTI 136971 10025 60-01-71-00189 CHANDRA KAMI JUMLA PATARASI JAYA LAL KAMI 136974 10026 151086/205 PRABIN YADAV DHANUSHA MARCHAIJHITAKAIYA JAYA NARAYAN YADAV 136976 10030 1012/81328 SABINA NAGARKOTI KATHMANDU DAANCHHI HARI KRISHNA NAGARKOTI 136984 10032 1039/16713 BIRENDRA PRASAD GUPTABARA KARAIYA SAMBHU SHA KANU 136988 10033 28-01-71-05846 SURESH JOSHI LALITPUR LALITPUR U.M.N.P. RAJU JOSHI 136990 10034 331071/6889 BIJAYA PRASAD YADAV BARA RAUWAHI RAM YAKWAL PRASAD YADAV 136993 10036 071024/932 DIPENDRA BHUJEL DHANKUTA TANKHUWA LOCHAN BAHADUR BHUJEL 136996 10037 28-01-067-01720 SABIN K.C. -

TSLC PMT Result

Page 62 of 132 Rank Token No SLC/SEE Reg No Name District Palika WardNo Father Mother Village PMTScore Gender TSLC 1 42060 7574O15075 SOBHA BOHARA BOHARA Darchula Rithachaupata 3 HARI SINGH BOHARA BIMA BOHARA AMKUR 890.1 Female 2 39231 7569013048 Sanju Singh Bajura Gotree 9 Gyanendra Singh Jansara Singh Manikanda 902.7 Male 3 40574 7559004049 LOGAJAN BHANDARI Humla ShreeNagar 1 Hari Bhandari Amani Bhandari Bhandari gau 907 Male 4 40374 6560016016 DHANRAJ TAMATA Mugu Dhainakot 8 Bali Tamata Puni kala Tamata Dalitbada 908.2 Male 5 36515 7569004014 BHUVAN BAHADUR BK Bajura Martadi 3 Karna bahadur bk Dhauli lawar Chaurata 908.5 Male 6 43877 6960005019 NANDA SINGH B K Mugu Kotdanda 9 Jaya bahadur tiruwa Muga tiruwa Luee kotdanda mugu 910.4 Male 7 40945 7535076072 Saroj raut kurmi Rautahat GarudaBairiya 7 biswanath raut pramila devi pipariya dostiya 911.3 Male 8 42712 7569023079 NISHA BUDHa Bajura Sappata 6 GAN BAHADUR BUDHA AABHARI BUDHA CHUDARI 911.4 Female 9 35970 7260012119 RAMU TAMATATA Mugu Seri 5 Padam Bahadur Tamata Manamata Tamata Bamkanda 912.6 Female 10 36673 7375025003 Akbar Od Baitadi Pancheswor 3 Ganesh ram od Kalawati od Kalauti 915.4 Male 11 40529 7335011133 PRAMOD KUMAR PANDIT Rautahat Dharhari 5 MISHRI PANDIT URMILA DEVI 915.8 Male 12 42683 7525055002 BIMALA RAI Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Man Bahadur Rai Gauri Maya Rai Ghodghad 915.9 Female 13 42758 7525055016 SABIN AALE MAGAR Nuwakot Madanpur 4 Raj Kumar Aale Magqar Devi Aale Magar Ghodghad 915.9 Male 14 42459 7217094014 SOBHA DHAKAL Dolakha GhangSukathokar 2 Bishnu Prasad Dhakal -

District Profile - Dolakha (As of 10 May 2017) HRRP

District Profile - Dolakha (as of 10 May 2017) HRRP This district profile outlines the current activities by partner organisations (POs) in post-earthquake recovery and reconstruction. It is based on 4W and secondary data collected from POs on their recent activities pertaining to housing sector. Further, it captures a wide range of planned, ongoing and completed activities within the HRRP framework. For additional information, please refer to the HRRP dashboard. FACTS AND FIGURES Population: 280,8741 48 VDCs and 2 municipalities Damage Status - Private Structures Type of housing walls Dolakha National Mud-bonded bricks/stone 92% 41% Cement-bonded bricks/stone 5% 29% Damage Grade (3-5) 56,293 Other 3% 30% Damage Grade (1-2) 4,346 % of households who own 94% 85% Total 60,6392 their housing unit (Census 2011)1 NEWS & UPDATES 1. NRA Dolakha is planning to do survey of buildings which were missed out or where people were not convinced by the previous survey. NRA is planning to use the same DLPIU Engineers for the survey. The start date is yet to be finalized because of the election. 2. Bhimeshwor Municipality ward 1 (new) Bosimpa has been identified as one major village to resettle and they are planning to resettle 82 HH to Panipokhari. This is also taken as major pilot resettlement project in Dolakha. HRRP Dolakha HRRP © PARTNERS SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS3 Partner Organisation Implementing Partner(s) BC PLAN 2,338 1,645 CA CEEPAARD,HURADEC SHORT TRAINING CARITAS - L POURAKHI VOCATIONAL TRAINING 599 5,398 CARITAS-N (Targets Achieved) CW RRN -

District Profile - Dolakha (As of 10 Apr 2017) HRRP

District Profile - Dolakha (as of 10 Apr 2017) HRRP This district profile outlines the current activities by partner organisations (POs) in post-earthquake recovery and reconstruction. It is based on 4W and secondary data collected from POs on their recent activities pertaining to housing sector. Further, it captures a wide range of planned, ongoing and completed activities within the HRRP framework. For additional information, please refer to the HRRP dashboard. FACTS AND FIGURES Population: 280,8741 48 VDCs and 2 municipalities Damage Status - Private Structures Type of housing walls Dolakha National Mud-bonded bricks/stone 92% 41% Cement-bonded bricks/stone 5% 29% Damage Grade (3-5) 56,293 Other 3% 30% Damage Grade (1-2) 4,346 % of households who own 94% 85% Total 60,6392 their housing unit (Census 2011)1 NEWS & UPDATES 1. HRRP Dolakha jointly visited different VDC with NRA CEO Dr. Gobinda Raj Pokhrel, Dist. DUDBC Chief Mr. Yek Raj Adhikari, Dist. MOFALD Chief Narayan Siwakoti and Dist. NRA Chief Mr. Sagar Acharya to see the houses built and mason trained in the respective VDCs. 2. Reconstruction in Dolakha district is in rapid pace whereas 4,500 houses are being constructed and more than 4,000 are completed among which 10% are not in compliance with government standard. NSET-Dolakha © PARTNERS SUMMARY AND HIGHLIGHTS3 Partner Organisation Implementing Partner(s) BC PLAN 2,251 1,732 CA CEEPAARD,HURADEC SHORT TRAINING CARITAS - L POURAKHI VOCATIONAL TRAINING 551 5,446 CARITAS-N (Targets Achieved) CW RRN Reached Remaining GAN CEEPAARD HELVETAS KITES,AFD,CS IOM REDR-I,CWIN-TUKI 11 Demonstration Constructions in 11 VDCs/Municipalties LWF HURADEC MC REDC NRCS NSET 0 VDC with Household WASH Assistance PLAN SCI RDTA SOS 48,114 beneficiaries enrolled, 92% UNDP UNHABITAT 48,077 beneficiaries received the 1st Tranche, 91%4 17 partners This table indicates the partner organisations and their respective implementing partner(s) NPR 246 houses provided with Housing Grants by POs KEY CONTACTS DAO OFFICE DDC OFFICE NRA District Office DUDBC OFFICE Mr. -

Initial Environmental Examination

Initial Environmental Examination Sunkhani – Lamidanda - Kalinchok Section of Sunkhani - Sangwa Road Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Sub- project June 2017 NEP: Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project Prepared by District Coordination Committee (Dolakha)- Central Level Project Implementation Unit – Ministry of Federals Affairs and Local Development for the Asian Development Bank. This initial environmental examination is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent those of ADB's Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. Your attention is directed to the “terms of use” section on ADB’s website. In preparing any country program or strategy, financing any project, or by making any designation of or reference to a particular territory or geographic area in this document, the Asian Development Bank does not intend to make any judgments as to the legal or other status of any territory or area. Environmental Assessment Document Initial Environmental Examination (IEE) Sunkhani – Lamidanda - Kalinchok Section of Sunkhani - Sangwa Road Rehabilitation and Reconstruction Sub-project June 2017 NEP: Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project Loan: 3260 Project Number: 49215-001 Prepared by the Government of Nepal for the Asian Development Bank (ADB). This Report is a document of the borrower. The views expressed herein do not necessarilyThe views expressed represent herein those are those of ADB's of the consultantBoard of and Directors, do not necessarily Management, represent or thosestaff ,of and ADB’s may bemembers, preliminary Board ofin Directors,nature. Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. The views expressed herein are those of the consultant and do not necessarily represent those of ADB’s members, Board of Directors, Management, or staff, and may be preliminary in nature. -

Sansodhit Name List from NRA Dolakha.Xlsx

िजलाका संशोधत लाभ ाह!ह"को नामावल! स .नं. सझौता . सं. स .नं. संशोधन हुन ु पन संशोधत नाम िजला गा .व .स./न.पा वडा 1 G-22-4-11-0-141 442 Chitra Prasad Dahal Namraj Dahal Dolakha 2 G-22-2-1-0-001 443 Amrit Bahadur Thami Yegye Bahadur Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 1 3 G-22-2-1-0-002 444 Dhana Sing Thami Sharmila Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 1 4 G-22-2-1-0-003 445 Purna Bahadur Thami Mangali Maya Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 1 5 G-22-2-1-0-005 446 Chhabi Thami Maha Bir Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 1 6 G-22-2-1-0-006 447 Gofle Thami Menuka Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 1 7 G-22-2-1-0-007 448 Santa Bir Thami Amrit Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 1 8 G-22-2-1-0-010 449 Gore Thami Dolma Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 1 9 G-22-2-1-0-011 450 Saru Man Thami Lal Maya Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 1 10 G-22-2-1-0-012 451 Padam Thami Ganesh Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 11 G-22-2-1-0-013 452 Lal Bahadur Thami Sante Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 12 G-22-2-1-0-015 453 Saru Man Thami Rajiv Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 13 G-22-2-2-0-001 454 Som Bahadur Thami Chandra Bahadur Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 14 G-22-2-2-0-003 455 Man Bahadur Thami Bhim Bahadur Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 15 G-22-2-2-0-004 456 Uush Kumar Thami Sanchi Maya Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 16 G-22-2-2-0-007 457 Yagye Bahadur Thami Jhalak Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 17 G-22-2-2-0-008 458 Pahal Bahadur Thami Nara Maya Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 18 G-22-2-2-0-009 459 Pahal Bahadur Thami Maitali Maya Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 19 G-22-2-2-0-011 460 Saruni Thami Som Bahadur Thami Dolakha Babare Vdc 2 20 G-22-2-2-0-012 461 Mahal Bahadur Thami -

Dolakhatopographic Map - June 2015

fh N e p a l DolakhaTopographic Map - June 2015 3 000m. 4 4 4 4 4 4 4 000m. N N . 91 E 92 93 85°55'9E4 95 96 97 98 99 00 01 86°0E2 03 04 05 06 07 08 09 8160°5'E 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 1868°10'E 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 2686°15'E 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 86°20'E35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 86°254'E3 44 45 46 47 48 49 50 86°5301'E 52 53 54 55 56 E. m m 0 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 1 1 1 1 3 3 17 17 17 17 N ' 0 1 ° N 8 5 ' 2 16 160 16 4 16 0 1 0 ° 8 2 15 15 15 15 5 2 0 T 14 0 14 14 50 14 a 00 m b 13 13 a 13 13 0 K 80 4 4 6 o 0 s 0 0 12 12 00 20 12 12 i 44 4 4 4 0 0 0 11 0 11 11 Lapchegaun 2 11 ! 4 0 000 0 31 5 31 4 i 10 4 10 10 4800 0 10 s 0 0 4 4 0 5 8 6 o 0 4 0 K 0 09 09 60 0 09 09 4 60 4 a 5000 b 08 5 m 08 6 08 08 0 0 0 a 0 0 0 0 0 8 8 0 4 5 T 0 5 0 5 N ' 0 4 5 5 0 07° 07 8 0 07 07 N 2 ' 5 0 ° Gumba 0 8 6 2 3800 5 06 06 06 06 0 0 8 5 4 6 Thasing ! 0 05 0 05 5 05 05 0 0 5 0 40 0 0 4 4 0 0 C H I N A 6 0 4 2 0 5 0 0 0 00 0 8 5 0 0 4 04 0 5 54 04 0 04 3 04 0 4800 u 0 0 4 h 6 0 600 5 0 C 4 0 4 0 2 0 4 0 5 0 00 r 03 0 5 0 6 03 0 03 0 0a3 0 0 6 6 5 5 h 0 0 Thangchhemu s 2 0 ! g 6 5 R o n 8 4 0 80 0 02 0 02 02 02 0 0 6 4 4 4 5 0 0 i 2 01 0 0 01 44 01 0 01 h 0 f s 5 ! 6 0 4 o 0 31 2 Lomnang 31 0 ! 00 0 K 00 00 5 00 4 0 e 0 0 f 0 600 ! 0 0 6 3 t 0 8 2 4 4 5 4 5 5 0 40 0 56 0 0 0 o 0 0 0 0 5 99 Tarkeghang 0 0 56 400 99 0 99 Lumnang 99 3 3 0 f 6 h 0 ! 2 3 0 0 4 ! 0 0 4 5 f 0 B 4 0 0 f 6 ! 4 Pangbuk 0 3 ! ! 0 0 6 0 0 5200 4 Pangbuk 98 0 98 N 0 98 98 ° 3 0 Goth 8 ! 2 N ° 5 3200 8 2 2 0 97 3 5 0 97 60 3 6 97 97 0 2 38 0 0 3 0 0 0 8 0 0 0 f 4 96 00 50 96 ! 0 Tatopani 18 96 0 -

Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project Dolakha Chainage

Government of Nepal Ministry of Federal Affairs and Local Development Central Level Project Implementation Unit Earthquake Emergency Assistance Project Lalitpur, Nepal (ADB Loan 3260-NEP) Gender Equality and Social Inclusion Action Plan (GESI-AP) Sunkhani-Sangwa Sub -project Dolakha Chainage: (O+000 - 27+373) May, 2017 Table of Contents 1.Background ............................................................................................................................. 2 Occupation ............................................................................................................................... 3 Cast ethnic, indigenous, Dalit and minorities of the sub-project. ..................................................... 4 2.1 Demographic Information of the Project Area ........................................................................ 5 3.Situation Analysis of Women .................................................................................................... 6 4.Proposed Activities of GESI-AP for this sub-project .......................................................... 9 4.1 Expected objectives of GESI-AP for this sub-project: ................................................... 9 5. Estimated budget for conducting GESI-AP for Sunkhani – Sangwa – Lamidanda- Kalinchowk sub project. .........................................................................................................10 6. Details cost breakdown. ......................................................................................................11