National Legislative Framework for Water User Associations out of Sync with Traditional Institutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

La Apropiación Territorial Del Municipio Del Uxpanapa, Veracruz

IV Congreso Chileno de Antropología. Colegio de Antropólogos de Chile A. G, Santiago de Chile, 2001. La Apropiación Territorial del Municipio del Uxpanapa, Veracruz. Micaela Rosalinda Cruz. Cita: Micaela Rosalinda Cruz. (2001). La Apropiación Territorial del Municipio del Uxpanapa, Veracruz. IV Congreso Chileno de Antropología. Colegio de Antropólogos de Chile A. G, Santiago de Chile. Dirección estable: https://www.aacademica.org/iv.congreso.chileno.de.antropologia/110 Acta Académica es un proyecto académico sin fines de lucro enmarcado en la iniciativa de acceso abierto. Acta Académica fue creado para facilitar a investigadores de todo el mundo el compartir su producción académica. Para crear un perfil gratuitamente o acceder a otros trabajos visite: https://www.aacademica.org. 3. Barahona, Rafael; Aranda, Ximena; Santana, Roberto, 5. Bengoa, José, Historia social de Ja agricultura chilena. El valle de Putaendo, estudio de estructura agraria. U. Tomo 11: "Hacienda y campesinos': Edic. Sur, 1990. de Chile, Instituto de Geografía. Santiago de Chile, 6. Domi, e K, Len ka, La vida rural en el distrito de 1961. Chacabuco: norte de la cuenca de Santiago, Santiago, 4. Bauer, Anold, La sociedad rural chilena. Desde Ja con 1959. Tesis Universidad de Chile. quista española hasta nuestros días. Edit. Andrés Be llo, 1975. La Apropiación Territorial del Municipio del Uxpanapa, Veracruz Micaela Rosalinda Cruz El propósito del presente trabajo es analizar el proceso con otros individuos, constituyeron varias sociedades de apropiación territorial del municipio del Uxpanapa, anónimas para explorar y explotar las riberas del Veracruz, a partir de los mecanismos que han permiti Coatzacoalcos. En ese entonces, el gobierno del esta do dicha apropiación. -

Colonial Spanish Terms Compilation

COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS COMPILATION Of COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS And DOCUMENT RELATED PHRASES COMPILATION Of COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS file:///C|/...20Grant%202013/Articles%20&%20Publications/Spanish%20Colonial%20Glossary/COLONIAL%20SPANISH%20TERMS.htm[5/15/2013 6:54:54 PM] COLONIAL SPANISH TERMS And DOCUMENT RELATED PHRASES Second edition, 1998 Compiled and edited by: Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Navarro Wold Copyright, 1998 Published by: SHHAR PRESS, 1998 (Society of Hispanic Historical and Ancestral Research) P.O. Box 490 Midway City, CA 92655-0490 1-714-894-8161 Cover: Census Bookcover was provided by Ophelia Marquez . In 1791, and again in 1792, a census was ordered throughout the viceroyalty by Viceroy Conde de Revillagigedo. The actual returns came in during 1791 - 1794. PREFACE This pamphlet has been compiled in response to the need for a handy, lightweight dictionary of Colonial terms to use while reading documents. This is a supplement to the first edition with additional words and phrases included. Refer to pages 57 and 58 for the most commonly used phrases in baptismal, marriage, burial and testament documents. Acknowledgement Ophelia and Lillian want to record their gratitude to Nadine M. Vasquez for her encouraging suggestions and for sharing her expertise with us. Muy EstimadoS PrimoS, In your hands you hold the results of an exhaustive search and compilation of historical terms of Hispanic researchers. Sensing the need, Ophelia Marquez and Lillian Ramos Wold scanned hundreds of books and glossaries looking for the most correct interpretation of words, titles, and phrases which they encountered in their researching activities. Many times words had several meanings. -

Registro Vias Pecuarias Provincia De Almeria

COD_VP Nombre COD.TRAMO PROVINCIA MUNICIPIO ESTADO LEGAL ANCHO PRIORIDAD USO PUBLICO LONGITUD 04001001 CORDEL DE GRANADA A ALMERIA 04001001_01 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 38 1 520 04001001 CORDEL DE GRANADA A ALMERIA 04001001_02 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 38 1 1446 04001001 CORDEL DE GRANADA A ALMERIA 04001001_03 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 38 1 2140 04001001 CORDEL DE GRANADA A ALMERIA 04001001_04 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 38 2 999 04001002 CORDEL DE ESCULLAR 04001002_01 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 38 1 11 04001002 CORDEL DE ESCULLAR 04001002_02 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 38 0 2964 04001002 CORDEL DE ESCULLAR 04001002_03 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 38 1 1379 04001003 VEREDA DE OHANES 04001003_01 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 21 1 293 04001003 VEREDA DE OHANES 04001003_02 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 21 0 1507 04001004 VEREDA DEL SERVAL 04001004_01 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 21 1 3036 04001004 VEREDA DEL SERVAL 04001004_02 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 21 1 103 04001005 VEREDA DEL CAMINO DE ESCULLAR 04001005_01 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 21 1 639 04001005 VEREDA DEL CAMINO DE ESCULLAR 04001005_02 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 21 1 11 04001005 VEREDA DEL CAMINO DE ESCULLAR 04001005_03 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 21 1 1251 04001007 COLADA DEL MORAL 04001007_01 ALMERIA ABLA CLASIFICADA 4 1 1058 04002001 CORDEL DE ESCULLAR 04002001_01 ALMERIA ABRUCENA CLASIFICADA 38 0 621 04002001 CORDEL DE ESCULLAR 04002001_02 ALMERIA ABRUCENA CLASIFICADA 38 0 1258 04002002 CORDEL DE GRANADA A ALMERIA 04002002_01 ALMERIA ABRUCENA CLASIFICADA 38 1 933 04002002 CORDEL DE GRANADA A ALMERIA 04002002_02 -

Normas Generales Para El Uso De Abreviaturas En El Instituto Geográfico Nacional

Normas generales para el uso de abreviaturas en el Instituto Geográfico Nacional FUNDAMENTOS Actualmente existe una gran heterogeneidad en la forma de abreviar los nombres geográficos, debido a que cada organismo que confecciona cartografía, tanto a nivel estatal como privado, tiene su propio criterio para realizar la abreviación, en especial de los nombres genéricos (como ejemplos podemos tomar las abreviaturas de puerto: pto. o pt., o punta: p. o pta.). Por este motivo surge la necesidad de confeccionar un listado único y normalizado de abreviaturas de los términos genéricos y específicos utilizados en la cartografía publicada por los organismos oficiales en la República Argentina. Siendo el Instituto Geográfico Nacional (IGN) junto con el Servicio de Hidrografía Naval (SHN) los organismos encargados de la confección de la cartografía oficial de la República Argentina según lo dispuesto en las leyes Nº 22963 – Ley de la Carta y Nº 19922 - Ley Hidrográfica respectivamente, hemos decidido compatibilizar las abreviaturas del IGN a las de accidentes costeros y marinos utilizadas por el SHN. El uso de dicho “corpus” será recomendado para la confección de cartografía en todos los organismos del Estado para así propender a la normalización cartográfica, y estará disponible para su adopción por parte de la sociedad en general. Es preciso destacar la existencia de abreviaturas normalizadas en el IGN en el Manual de Signos Cartográficos en sus diversas ediciones, pero se considera necesaria su revisión también con el objetivo de adoptar las abreviaturas de uso común por parte de la sociedad, la incorporación de nuevos objetos geográficos como consecuencia de la aprobación del Catálogo de objetos del IGN en abril de 2015 y la próxima implementación de un proceso de edición automatizada de cartografía. -

Open Dennison Final Thesis.Pdf

THE PENNSYLVANIA STATE UNIVERSITY SCHREYER HONORS COLLEGE DEPARTMENT OF POLITICAL SCIENCE STRUCTURAL DETERMINANTS OF OPPOSITION PARTY SUPPORT UNDER AN ELECTORAL CAUDILLO Kristen M. Dennison Spring 2011 A thesis submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for baccalaureate degrees in International Politics and International Studies with honors in Political Science Reviewed and approved* by the following: David J. Myers Associate Professor of Political Science Thesis Supervisor Michael B. Berkman Professor of Political Science Honors Adviser *Signatures are on file in the Schreyer Honors College ABSTRACT An electoral caudillo is a semi-democratic leader who manipulates electoral contests to maintain his hold on executive power. In Latin America, this type of strong central leadership has become increasingly popular as citizens seek alternatives to democratic systems which they view as corrupt and inefficient. However, authoritarian qualities of electoral caudillo rule can prevent democratic consolidation and national development. This paper examines the structural characteristics of electoral caudillismo, specifically noting factors which may lead to increased opposition party support. Those factors are tested using a unique municipio-level dataset, which suggests that low levels of government funding, high quality of life, and weak clientelistic networks of the previous party system are associated with higher levels of opposition support. The data also underscore the importance of political contention which adheres to the minimum -

Boletín Demográfico Del Municipio De El Ejido 2006

Boletín Demográfico del Municipio de El Ejido - 2006 Excmo. Ayuntamiento de El Ejido Unidad de Gestión de Población 2 Boletín Demográfico del Municipio de El Ejido - 2006 Excmo. Ayuntamiento de El Ejido Unidad de Gestión de Población Boletín demográfico del Municipio de El Ejido 2006 Unidad de Gestión de Población Área de Régimen Interior y Personal Ayuntamiento de El Ejido 3 Boletín Demográfico del Municipio de El Ejido - 2006 Excmo. Ayuntamiento de El Ejido Unidad de Gestión de Población Datos catalográficos BOLETÍN demográfico del Municipio de El Ejido 2006 Unidad de Gestión de Población: 2006 136 p.; 20 cm. (Estadísticas demográficas) D.L. –AL.- 437 -2005. C.D.U.:341.04 (460.358 El Ejido) Movimientos demográficos Autor: Pedro Cañabate Gómez Diseño de portada: José Ramón Ortiz Bretones Coordinador: Miguel Clement Martín Año de Edición: 2006- Excmo. Ayuntamiento de El Ejido © Ayuntamiento de El Ejido I.S.S.N: 1698-8345 Depósito Legal: AL.- 437 –2005 Tirada: 10.000 ejemplares Imprenta Grafisur (El Ejido) Impreso en Andalucía 4 Boletín Demográfico del Municipio de El Ejido - 2006 Excmo. Ayuntamiento de El Ejido Unidad de Gestión de Población ÍNDICE GENERAL Página SALUDO Y PRESENTACIÓN 7 INTRODUCCIÓN 9 1. EVOLUCIÓN DE LA POBLACIÓN: 1900 a 2006. 11 2. CAMBIOS EN LA ESTRUCTURA DE LA POBLACIÓN. 19 3. LA POBLACIÓN ACTUAL: CARACTERÍSTICAS BÁSICAS. 33 4. POBLACIÓN DE NACIONALIDAD EXTRANJERA. 57 4.1. La población de nacionalidad extranjera en el municipio. 58 4.2. Características de la población de nacionalidad extranjera en el municipio. 63 4.3. La población de origen extranjero en las diferentes Entidades de Población. -

Coahuila CUEVAS, LAS ARTEAGA NUNCJO ARTEAGA * Se Refiere a 'Cocina Exclusiva"

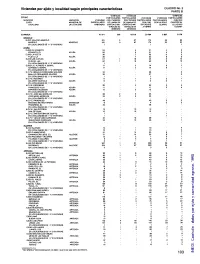

Viviendas por ejido y localidad segun principales caracteristicas CUADRO No. 2 PARTE B VIVIENDAS VIVIENDAS VIVIENDAS ESTADO PARTICULARES PARTICULAR ES VIVIENDAS VIVIENDAS PARTICULARES MUNICIPIO UBICACION VIVIENDAS CON PAREDES CON TECHOS PARTICULARES PARTICULARES CON DOS EJIDO MUNICIPAL DE PARTICULARES DE LAMINA DE DE LAMINA DE CONPISO CON UN SOLO CUARTOSIN- LOCALIDAD LALOCAUDAD HABITADAS CARTON 0 MA- CARTON 0 MA- DIFERENTE CUARTO CLUYENDO TERIALES DE TERIALES DE ATlERRA COCINA' DESECHO DESECHO ABASOLO EJIDO VILLA DE ABASOLO ABASOLO EN LOCALIDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS ACUNA EJIDO EL VENADITO VENADITO. EL AC UNA EJIDO LA PILETA PILETA, LA AC UNA EJIDO LAS CUEVAS CUEVAS. LAS ACUNA EN LOCALIDADES DE i Y 2 VIVIENDAS EJIDO LIC. ALFREDO V. BONFIL ALFREDO V. BONFIL ACUNA EN LOCAUDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS N.C.P.E. BRAUUO FERNANDEZ AGUIRRE BRAUUO FERNANDEZ AGUIRRE EN LOCALIDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS N.C.P.E. DOLORES DOLORES VALENCIA EN LOCAUDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS N.C.P.E. ESCOBEDO FRANCISCO VILLA ACUNA MARIANO ESCOBEDO ACUNA EN LOCALIDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS N.C.P.E. JOSE MA. MORELOS JOSE MARIA MORELOS EN LOCALIDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS N.C.P.E. PROGRESO DIECISEIS MIL HECTAREAS ZARAGOZA PROGRESO, EL ACUNA EN LOCALIDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS N.C.P.E. SAN ESTEBAN SAN ESTEBAN N.C.P.E. SAN ESTEBAN DE EGIPTO EN LOCALIDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS N.C.P.E VENUSTIANO CARRANZA VENUST1ANO CARRANZA EN LOCALIDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS ALLENDE EJIDO ALLENDE EN LOCALIDADES DE 1 Y 2 VIVIENDAS EJIDO CHAMACUERO CHAMACUERO (SEIS. -

Porfirian Sugar and Rum Production in Northeastern Yucatán

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA RIVERSIDE Bittersweet: Porfirian Sugar and Rum Production in Northeastern Yucatán A Dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Anthropology by John R Gust June 2016 Dissertation Committee: Dr. Scott L. Fedick, Chairperson Dr. Wendy Ashmore Dr. Karl Taube Dr. Robert W. Patch Copyright by John R Gust June 2016 The Dissertation of John R Gust is approved: Committee Chairperson University of California, Riverside Acknowledgements Permission to conduct this research was granted by the Consejo de Arqueología of the Instituto Nacional de Antropología e Historia (INAH). I would like to express my thanks to Dra María de los Angeles Olay Barrientos, and the other Consejo members for their support. In Quintana Roo, Arqlga. Adriana Velázquez Morlet, director of INAH Quintana Roo, as well as the staff for all the help they provided. Thank you to Drs. John Morris and Jaime Awe of the Belize Institute of Archaeology for allowing me access to the artifact collection from San Pedro Siris and for permission to visit and photograph Belizean sugar mill sites. This research was possible with the aid of small grants from UC-MEXUS and a UCR Humanities grant. A project like this is impossible without the aid of a multitude of people including some who are so behind the scenes whose name I will never know. I want to next thank those people, and the people whose names I have forgotten for their important contributions. My dissertation committee, especially my advisor Scott Fedick, has supported me constantly throughout this long process. -

Nucleos Agrarios Que Adoptaron El Dominio Pleno De Parcelas Ejidales Y Aportación De Tierras De Uso Común a Sociedades Mercantiles

Nucleos Agrarios que Adoptaron el Dominio Pleno de Parcelas Ejidales y Aportación de Tierras de Uso Común a Sociedades Mercantiles SUPERFICIE EN HS. No. ESTADO MUNICIPIO NUCLEO AGRARIO U. C. APORTADA 1 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES AGOSTADERITO 2 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES ARELLANO 3 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES BUENAVISTA 4 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES CABECITA TRES MARIAS (RES. PRES. 02/10/40) 5 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES CALVILLITO (RES. PRES. 25/11/26) 6 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES CAÑADA HONDA 7 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES CENTRO DE ARRIBA (EL TARAY) 8 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES COTORINA 9 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES EL CEDAZO 10 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES EL COLORADO 11 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES EL CONEJAL 12 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES EL GUARDA Y SU ANEXO COBOS Y EL MALACATE. 13 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES EL NIAGARA 14 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES EL REFUGIO DE PEÑUELAS 15 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES EL ZOYATAL 16 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES JALTOMATE 17 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES LA TERESA 18 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES LA TINAJA 19 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES LAS CUMBRES 20 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES LOS DURON O LOS DURONES 21 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES LOS NEGRITOS 22 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES LOS POCITOS Y ANEXOS 23 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES MONTORO 24 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES NORIAS DE PASO HONDO 25 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES OJOCALIENTE 26 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES PEÑUELAS 27 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES SALTO DE LOS SALADOS 28 AGUASCALIENTES AGUASCALIENTES -

Normas Técnicas Para La Delimitación De Las Tierras Al Interior Del Ejido

Normas técnicas para la delimitación de las tierras al interior del ejido 217 218 Normas técnicas para la delimitación de las tierras al interior del ejido* En cumplimiento a lo dispuesto por el artículo 56 fracción III de la Ley Agraria y del artículo 9o. fracción XX del Reglamento Interior del Registro Agrario Nacional, y con la finalidad de que la asamblea de ejidatarios cuente con los elementos técnicos necesarios para llevar a cabo la delimitación de tierras al interior del ejido, tengo a bien expedir las siguientes: Normas técnicas I. Lineamientos generales a) Contar con el plano general del ejido, que haya sido elaborado por la autoridad competente, o el que elabore el Registro Agrario Nacional. b) Contar con el acta aprobatoria de asamblea de ejidatarios en la que se asentó el acuerdo sobre la delimitación de las tierras al interior del ejido. c) Planear el levantamiento de campo y seleccionar el método a utilizar. d) Llevar a cabo el levantamiento de campo de acuerdo con el siguiente esquema: d.1 Reconocimiento general de las áreas y los predios a medir. d.2 Monumentación de las estaciones de las líneas de control azimutal y lineal (puntos GPS). * Publicadas en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el 25 de septiembre de 1992. Incluye reformas expedidas el 22 de febrero de 1995, publicadas en el Diario Oficial de la Federación el 2 de marzo de 1995. 219 d.3 Medición o fotoidentificación de las áreas y de los predios. d.4 Levantamiento de cédulas de información: –De vértices geodésicos monumentados. –General al interior del ejido. -

Entidad / Municipio / Localidad

Nombre del Programa: Modalidad: Dependencia/Entidad: Unidad Responsable: Tipo de Evaluación: Año de la Evaluación: NOTA: Ámbito Geográfico ENTIDAD / MUNICIPIO / LOCALIDAD 01 AGUASCALIENTES 001 AGUASCALIENTES 0001 AGUASCALIENTES 0106 ARELLANO 0146 EL CONEJAL 0171 LOS CUERVOS (LOS OJOS DE AGUA) 0191 LOS DURON 0272 MATAMOROS 0291 LOS NEGRITOS 0292 EL NIAGARA (RANCHO EL NIAGARA) 0296 EL OCOTE 0357 NORIAS DEL PASO HONDO 0379 SAN IGNACIO 0389 SAN JOSE DE LA ORDEÑA 0410 SAN PEDRO CIENEGUILLA 0422 SANTA CRUZ DE LA PRESA (LA TLACUACHA) 0461 EL TRIGO (TANQUE EL TRIGO) 0479 VILLA LIC. JESUS TERAN (CALVILLITO) 0584 EL GIGANTE (ARELLANO) 0648 NORIAS DE CEDAZO (CEDAZO NORIAS DE MONTORO) 0988 LOMAS DE ARELLANO 1025 POCITOS 9994 SAN ANTONIO DE PADUA 002 ASIENTOS 0002 LAS ADJUNTAS 0007 BIMBALETES AGUASCALIENTES (EL ALAMO) 0011 CIENEGA GRANDE 0015 CHARCO AZUL 0024 GORRIONES 0025 GUADALUPE DE ATLAS 0027 JARILLAS 0035 NORIA DEL BORREGO (NORIAS) 0036 OJO DE AGUA DE ROSALES 0037 OJO DE AGUA DE LOS SAUCES 0041 EL POLVO 0051 SAN RAFAEL DE OCAMPO 0053 TANQUE DE GUADALUPE 003 CALVILLO 0009 BARRANCA DE PORTALES 0021 EL CUERVERO (CUERVEROS) 0024 CHIQUIHUITERO (SAN ISIDRO) 0033 JALTICHE DE ARRIBA 0036 LA LABOR 0043 MALPASO 0055 OJOCALIENTE 0059 PALO ALTO 0060 LA PANADERA 0064 LOS PATOS 0069 PRESA DE LOS SERNA 0078 EL RODEO 0084 SAN TADEO 0095 EL TERRERO DE LA LABOR (EL TERRERO) 0096 EL TERRERO DEL REFUGIO (EL TERRERO) 0171 PUERTA DE FRAGUA (PRESA LA CODORNIZ) 004 COSIO 0001 COSIO 0025 EL REFUGIO DE PROVIDENCIA (PROVIDENCIA) 0026 LA PUNTA 0028 EL REFUGIO DE AGUA ZARCA -

ORDENANZA Nº 1875/04 VISTO: Las Facultades Conferidas a Este Cuerpo Por La Ley Orgánica De Municipalidades Nº 236/84, El Diag

ORDENANZA Nº 1875/04 VISTO: Las facultades conferidas a este Cuerpo por la Ley Orgánica de Municipalidades Nº 236/84, el Diagnóstico Urbano Expeditivo (años 1987/1988) elaborado en el marco del convenio firmado entre la Municipalidad de Río Grande y la Secretaría de Vivienda y Ordenamiento Ambiental de la Nación (S.V.O.A.), la Ordenanza Nº 1258/00, el Programa de Municipios del Tercer Milenio (M3M) que se está desarrollando en el marco de un convenio entre la Municipalidad de Río Grande y el Banco Mundial; y CONSIDERANDO: Que la localización de una ciudad siempre responde a características fundantes de la misma; Que la existencia de dos recursos urbanísticos tan importantes como el río y el mar, deben ser considerados ejes prioritarios para el desarrollo de la ciudad; Que el Ejecutivo Municipal ha manifestado en diversas oportunidades su decisión de mejorar la calidad de vida de los riograndenses; Que existe la necesidad de la comunidad de Río Grande de contar con espacios identitarios a nivel urbano; Que la documentación generada en el Departamento Ejecutivo Municipal, durante más de (17) diecisiete años en la que se respalda técnicamente la conveniencia de jerarquizar estos dos recursos: el río y el mar, es clara y expeditiva; Que la comunidad de Río Grande tiene una demanda insatisfecha de contar con espacios de uso público a nivel comunitario en estos lugares tan significativos. POR ELLO: EL CONCEJO DELIBERANTE DE LA CIUDAD DE RÍO GRANDE SANCIONA LA SIGUIENTE ORDENANZA Art. 1°) DECLARESE áreas de interés para la Municipalidad de Río Grande (AIM) a nivel histórico, geográfico, cultural, turístico, paisajístico, sanitario, etc., al RÍO GRANDE y a la COSTA MARÍTIMA del ejido Municipal Art.