The Value of Investing in Canadian Downtowns October 2013 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tall Buildings: up up and Away?

expect the best Tall Buildings: Up Up and Away? by Marc Kemerer Originally published in Blaneys on Building (April 2011) There has been much debate about tall buildings (buildings over 12 storeys in height) in Toronto in the past number of years particularly due to the decreasing availability of development land, and the province and municipal forces on intensification – but how tall is too tall and where should tall buildings be permitted? Marc Kemerer is a municipal As we have reported previously, the City of Toronto continues to review proposals for tall towers partner at Blaney McMurtry , against its Tall Buildings Guidelines which set out standards for podiums, setbacks between sister with significant experience in towers and the like. Some of those Guidelines were incorporated into the City’s new comprehensive all aspects of municipal planning and development. zoning by-law (under appeal and subject to possible repeal by City Council - see the Planning Updates section of this issue) while the Guidelines themselves were renewed last year by City Marc may be reached directly Council for continued use in design review. at 416.593.2975 or [email protected]. Over the last couple of years the City has embarked on the “second phase” of its tall buildings review through the “Tall Buildings Downtown Project”. In connection with this phase, the City has recently released the study commissioned by the City on this topic entitled: “Tall Buildings: Inviting Change in Downtown Toronto” (the “Study”). The Study focused on three issues: where should tall buildings be located; how high should tall buildings be; and how should tall buildings behave in their context. -

Entuitive Credentials

CREDENTIALS SIMPLIFYING THE COMPLEX Entuitive | Credentials FIRM PROFILE TABLE OF CONTENTS Firm Profile i) The Practice 1 ii) Approach 3 iii) Better Design Through Technology 6 Services i) Structural Engineering 8 ii) Building Envelope 10 iii) Building Restoration 12 iv) Special Projects and Renovations 14 Sectors 16 i) Leadership Team 18 ii) Commercial 19 iii) Cultural 26 iv) Institutional 33 SERVICES v) Healthcare 40 vi) Residential 46 vii) Sports and Recreation 53 viii) Retail 59 ix) Hospitality 65 x) Mission Critical Facilities/Data Centres 70 xi) Transportation 76 SECTORS Image: The Bow*, Calgary, Canada FIRM PROFILE: THE PRACTICE ENTUITIVE IS A CONSULTING ENGINEERING PRACTICE WITH A VISION OF BRINGING TOGETHER ENGINEERING AND INTUITION TO ENHANCE BUILDING PERFORMANCE. We created Entuitive with an entrepreneurial spirit, a blank canvas and a new approach. Our mission was to build a consulting engineering firm that revolves around our clients’ needs. What do our clients need most? Innovative ideas. So we created a practice environment with a single overriding goal – realizing your vision through innovative performance solutions. 1 Firm Profile | Entuitive Image: Ripley’s Aquarium of Canada, Toronto, Canada BACKED BY DECADES OF EXPERIENCE AS CONSULTING ENGINEERS, WE’VE ACCOMPLISHED A GREAT DEAL TAKING DESIGN PERFORMANCE TO NEW HEIGHTS. FIRM PROFILE COMPANY FACTS The practice encompasses structural, building envelope, restoration, and special projects and renovations consulting, serving clients NUMBER OF YEARS IN BUSINESS throughout North America and internationally. 4 years. Backed by decades of experience as Consulting Engineers. We’re pushing the envelope on behalf of – and in collaboration with OFFICE LOCATIONS – our clients. They are architects, developers, building owners and CALGARY managers, and construction professionals. -

Schedule 4 Description of Views

SCHEDULE 4 DESCRIPTION OF VIEWS This schedule describes the views identified on maps 7a and 7b of the Official Plan. Views described are subject to the policies set out in section 3.1.1. Described views marked with [H] are views of heritage properties and are specifically subject to the view protection policies of section 3.1.5 of the Official Plan. A. PROMINENT AND HERITAGE BUILDINGS, STRUCTURES & LANDSCAPES A1. Queens Park Legislature [H] This view has been described in a comprehensive study and is the subject of a site and area specific policy of the Official Plan. It is not described in this schedule. A2. Old City Hall [H] The view of Old City hall includes the main entrance, tower and cenotaph as viewed from the southwest and southeast corners at Temperance Street and includes the silhouette of the roofline and clock tower. This view will also be the subject of a comprehensive study. A3. Toronto City Hall [H] The view of City Hall includes the east and west towers, the council chamber and podium of City Hall and the silhouette of those features as viewed from the north side of Queen Street West along the edge of the eastern half of Nathan Phillips Square. This view will be the subject of a comprehensive study. A4. Knox College Spire [H] The view of the Knox College Spire, as it extends above the roofline of the third floor, can be viewed from the north along Spadina Avenue at the southeast corner of Bloor Street West and at Sussex Avenue. A5. -

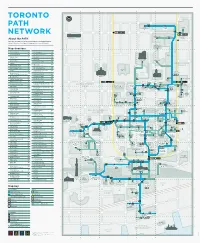

PATH Network

A B C D E F G Ryerson TORONTO University 1 1 PATH Toronto Atrium 10 Dundas Coach Terminal on Bay East DUNDAS ST W St Patrick DUNDAS ST W NETWORK Dundas Ted Rogers School One Dundas Art Gallery of Ontario of Management West Yonge-Dundas About the PATH Square 2 2 Welcome to the PATH — Toronto’s Downtown Underground Pedestrian Walkway UNIVERSITY AVE linking 30 kilometres of underground shopping, services and entertainment ST PATRICK ST BEVERLEY ST BEVERLEY ST M M c c CAUL ST CAUL ST Toronto Marriott Downtown Eaton VICTORIA ST Centre YONGE ST BAY ST Map directory BAY ST A 11 Adelaide West F6 One King West G7 130 Adelaide West D5 One Queen Street East G4 Eaton Tower Adelaide Place C5 One York D11 150 York St P PwC Tower D10 3 Toronto 3 Atrium on Bay F1 City Hall 483 Bay Street Q 2 Queen Street East G4 B 222 Bay E7 R RBC Centre B8 DOWNTOWN Bay Adelaide Centre F5 155 Wellington St W YONGE Bay Wellington Tower F8 RBC WaterPark Place E11 Osgoode UNIVERSITY AVE 483 Bay Richmond-Adelaide Centre D5 UNIVERSITY AVE Hall F3 BAY ST 120 Adelaide St W BAY ST CF Toronto Bremner Tower / C10 Nathan Eaton Centre Southcore Financial Centre (SFC) 85 Richmond West E5 Phillips Canada Life Square Brookfield Place F8 111 Richmond West D5 Building 4 Old City Hall 4 2 Queen Street East C Cadillac Fairview Tower F4 Roy Thomson Hall B7 Cadillac Fairview Royal Bank Building F6 Tower CBC Broadcast Centre A8 QUEEN ST W Osgoode QUEEN ST W Thomson Queen Building Simpson Tower CF Toronto Eaton Centre F4 Royal Bank Plaza North Tower E8 QUEEN STREET One Queen 200 Bay St Four -

390 Bay Street

Ground Floor & PATH Retail for Lease 390 Bay Street Eric Berard Sales Representative 647.528.0461 [email protected] RETAIL FOR LEASE 390 BAY ST 390 Bay Street CITY HALL OLD CITY EATON - CENTRE N.P. SQUARE HALL Queen St FOUR SEASONS CENTRE FOR THE PERFORMING ARTS University Ave Richmond St Wine Academy Bay St Bay York St York Yonge St Yonge Sheppard St Sheppard Church St Church Adelaide St FIRST CANADIAN PLACE SCOTIA PLAZA King St TORONTO DOMINION CENTRE COMMERCE COURT WALRUS PUB Wellington St ROYAL BANK BROOKFIELD PLAZA PLACE View facing south from Old City Hall OVERVIEW DEMOGRAPHICS (3KM, 2020) 390 Bay St. (Munich RE Centre) is located at northwest corner 702,631 of Bay St. and Richmond St. W within Toronto’s Financial Core. DAYTIME POPULATION It is a BOMA BEST Gold certified 378,984 sf A-Class office tower, with PATH connected retail. 390 Bay is well located with connec- $ $114,002 tivity to The Sheraton Centre, Hudson’s Bay Company/Saks Fifth AVG. HOUSEHOLD INCOME Avenue, Toronto Eaton Centre and direct proximity to Nathan Phillips Square and Toronto City Hall. Full renovations have been 182,265 completed to update the Lobby and PATH level retail concourse. HOUSEHOLDS RETAIL FOR LEASE 390 Bay Street "Client" Tenant Usable Area Major Vertical Penetration Floor Common Area Building Common Area UP DN UP DN Version: Prepared: 30/08/2016 UP FP2A Measured: 01/05/2019 390 Bay Street Toronto, Ontario 100 Floor 1 FHC ELEV GROUND FLOOR AVAILABILITY DN ELEC. UP ROOM ELEV ELEV DN Please Refer to Corresponding ELEV MECH. -

Fully Finished Class a Office Space in Downtown Winnipeg

VIEW ONLINE collierscanada.com/124587 Net Rental Rate: $8.00 PSF NET/ANNUM Contact us: Chris Cleverley Vice President +1 204 926 3830 [email protected] Sean Kliewer Vice President +1 204 926 3824 [email protected] Jordan Bergmann Sales Representative +1 204 954 1793 [email protected] FOR SUBLEASE | 200 Graham Avenue, Winnipeg | MB Colliers International 305 Broadway | 5th Floor Fully Finished Class A Office Winnipeg, MB | R3C 3J7 P: +1 204 943 1600 Space in Downtown Winnipeg F: +1 204 943 4793 200 Graham Avenue is located in the heart of downtown Winnipeg; walking distance to Portage and Main, True North Square, the Forks, BellMTS Place, RBC Convention Centre, The Exchange District, and Cityplace. Downtown is rapidly growing to become the central hub for work, live, and play. Accelerating success. FOR SUBLEASE | 200 Graham Avenue, Winnipeg Excellently located in downtown close to countless amenities Finished 15 min Hwy Access Transit Manned Skywalk Walk Score Parking Bicycle Space To Airport Score 92 Security Connected 98 On-Site Accessible THE AREA THE REGION DISTANCE Located in the heart of Downtown Amenities close to the subject Portage and Main 4 min. walk Winnipeg, 200 Graham Avenue is property include True North Shaw Park 5 min. walk a highly desirable office building. Square, City Place, BellMTS BellMTS Place 6 min. walk Being connected to the skywalk Place, RBC Convention Centre, system makes for easy commuting Hydro Place, Millennium Library, The Forks 12 min. walk through downtown and great The Forks, Portage and Main, access to many amenities. Winnipeg Square, etc. -

RETAIL SPACE for LEASE in the Heart of Downtown Winnipeg

305 Broadway, 5th Floor Winnipeg. MB R3C 3J7 COLLIERS INTERNATIONAL www.collierscanada.com RETAIL SPACE FOR LEASE In the heart of Downtown Winnipeg 333 St. Mary Avenue | Winnipeg, MB 2 OVERVIEW OVERVIEW 3 Available Space Civic Address 333 St. Mary Avenue Suite Area Availability 8,753 SF (up to 17,000 48 Immediately SF contiguous) 52 4,497 SF Immediately 68 815 SF Immediately Available 85 3,627 SF February 2020 93 945 SF Immediately 94 330 SF Immediately Skywalk Kiosk 400 SF Immediately Total GLA 448,000 SF Food Court Seating 520 Parking Stalls 1,370 • Climate controlled Skywalk to Bell MTS Place, True North Square, RBC Convention Centre, Millennium Library, Portage Avenue, and Main Street • Connected to major employers housing over 70,000 office employees Monday to Friday Features • Over 8,000 shoppers enter Cityplace each workday • 18 restaurants anchored by Boston Pizza and Shark Club • 7 loading doors, freight elevators, and large loading facility • 24/7 security, CCTV indoor/outdoor and foot patrols • Rooftop outdoor terrace on second level adjacent to the food court collierscanada.com collierscanada.com 4 MAIN FLOORPLAN MAIN FLOORPLAN 5 Main Floor 68 815 SF 85 3,627 SF 52 48 4,497 SF 8,753 SF collierscanada.com collierscanada.com 6 SECOND FLOORPLAN SECOND FLOORPLAN 7 Second Floor 400 SF 94 330 SF 93 945 SF collierscanada.com collierscanada.com 8 ON-SITE AMENITIES ON-SITE AMENITIES 9 On-site Amenities DINING From breakfast to a late night snack, Cityplace has something to satisfy every appetite. Visit one of our many Food Court merchants for a tasty bite. -

1 L;Kasdj Fkl; Kla;Sdj Fl;Kasj Dfkl;Sja Df

A&W TRADE MARKS LIMITED PARTNERSHIP (the “Partnership”) and A & W FOOD SERVICES OF CANADA INC. (“Food Services”) NINTH AMENDING AGREEMENT TO AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENCE AND ROYALTY AGREEMENT January 5, 2018 22483|3589363_2|RVEITCH NINTH AMENDING AGREEMENT TO AMENDED AND RESTATED LICENCE AND ROYALTY AGREEMENT This Ninth Amending Agreement made as of January 5, 2018 between A&W Trade Marks Limited Partnership, a limited partnership formed under the laws of British Columbia (the “Partnership”) and A & W Food Services of Canada Inc., a Canadian corporation (“Food Services”). WHEREAS the Partnership and Food Services entered into an Amended and Restated Licence and Royalty Agreement dated December 22, 2010, as amended January 5, 2011, January 5, 2012, January 5, 2013, January 5, 2014, January 5, 2015, January 5, 2016, December 19, 2016 and January 5, 2017 (as so amended, the “Licence and Royalty Agreement”) pursuant to which Schedule A thereto would be amended on an annual basis to add Proposed Additional A&W Outlets and to remove A&W Outlets that had Permanently Closed during the immediately preceding Reporting Period; AND WHEREAS Schedule B hereto sets out the Proposed Additional A&W Outlets to be added to the Royalty Pool on January 5, 2018, being the Adjustment Date for the Reporting Period commencing November 6, 2017; AND WHEREAS Schedule C hereto sets out the A&W Outlets that Permanently Closed during the Reporting Period ended November 5, 2017; AND WHEREAS Schedule D hereto sets out the conveyances and regrants of A&W Outlets contained in the Royalty Pool during the Reporting Period ended November 5, 2017; AND WHEREAS the parties hereto are desirous of amending the Licence and Royalty Agreement pursuant to the terms thereof to add the Proposed Additional A&W Outlets listed in Schedule B hereto to the Royalty Pool, to remove the Permanently Closed A&W Outlets listed in Schedule C hereto from the Royalty Pool, and to record the conveyances and regrants set out in Schedule D hereto. -

Sheldon Esbin Collection Inventory #618

page 1 Sheldon Esbin collection Inventory #618 File: Title: Date(s): Note: Call Number: 2012-031/001 (1) Artists. -- Cards in this file pertain to artists Ken Danby, 1981, 1984, 1991, Tracey Bowen, David Wright, Russell, David Crighton, 1994 Charles Pachter, and Conrad Furey. (2) Department stores : Eaton's [19--] (3) Department stores : Simpson's [19--], 1923 (4) Galleries and antiques [199-] (5) Hotels. -- File consists of advertising for the Rossin [18--], [19--] House Hotel, Ford Hotels, the Empress Hotel and the Islington Hotel. (6) Manufacturers : miscellaneous. -- Advertising for the 1892, [19--] following companies are included in this file: the J.L Morrison Co., Henry Wilkes & Co., the Trelford Manufacturing Co., William H. Bell & Co., J. Bibby & Sons, the Gutta Percha and Rubber Mfg. Co., the Toronto Biscuit & Confectionery Co., Queen City Oil Works, Toronto Steel Clad Bath Co., the Singer Manufacturing Co., Lamb Knitting Machine Manufacturing Co., the Canada Paint Co. Ltd., Badgley & Millar, the Universal Knitting Co., Common Sense Manufacturing Co., Clark's Spool Cotton. (7) Printers and publishers. -- Included in this file is [between 1872 and advertising for the publishing house of the "Toronto 1891], [19--] Mail", the Canadian Printing Company, and Charles Ashton & Potter Calendars. (8) Products : cosmetics, medicines and soaps. -- Products [19-?] documented in this file include Comfort Soap, Pears' Soap, Palmer's Perfumes, Soapine, St. Jacob's Oil, Burdock Blood Bitters, Wistar's Balsam of Wild Cherry, Ammonia Electric Soap, Infants Delight Toilet Soap, and Rodger, Maclay and Co.'s soaps. (9) Products : food. -- Products documented in this file 1886-1908 include Tetley's Tea, Heinz's Tomato Soup, Mantle's Famous Self-Raising Flour, Pure Gold Baking Powder, Fonner's Orangeade, Shirriff's Flavoring Extracts, and Peek Freen biscuits. -

LAKEVIEW SQUARE Premium Office for Lease in Downtown Winnipeg 175-185 Carlton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba

LAKEVIEW SQUARE Premium Office for Lease in Downtown Winnipeg 175-185 Carlton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba • Skywalk access • Shaw fiber internet • Underground parking • Newly renovated common areas • Build-to-suit opportunity FOR LEASE Lakeview Square, 175-185 Carlton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba Walker’s Paradise Commuter’s Hub • Walk to Bell MTS Place via skywalk • Excellent transit service • Close to numerous amenities • Walking distance to many routes Parking Building Amenities • Heated underground available • Recently renovated common areas • Elevator access from lobby • Card access controls Shaw Fiber On-Site Management • Download speeds up to 1 Gbps • On-site building engineer • Limited availability in Winnipeg • After-hours security guard 204.474.2000 www.shindico.com FOR LEASE Lakeview Square, 175-185 Carlton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba FEATURES PROPERTY SUMMARY • In close proximity to the RBC Convention Lease Rate TBN Centre Winnipeg, the Delta Hotel, Bell MTS Place, and True North Square. Property Taxes (est.) $2.77/SF • On-site restaurants include Ichiban Japanese CAM* (est.) $12.00/SF Restaurant, Shannon’s Irish Pub and Subway. • Within walking distance of shopping, many fine HVAC Central HVAC System dining establishments, entertainment venues, historic Exchange District and The Forks. Parking Underground Available Management On-Site Professional Mgmt. Security Card Access, Cameras *plus management fee 204.474.2000 www.shindico.com FOR LEASE Lakeview Square, 175-185 Carlton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba MAIN FLOOR AVAILABILITY 204.474.2000 www.shindico.com FOR LEASE Lakeview Square, 175-185 Carlton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba 3RD TO 6TH FLOORS AVAILABLE FOR LEASE Main Floor 828 & 1,209 SF 3rd Floor 6,991 SF 4th Floor 4,907 SF 5th Floor 6,991 SF 6th Floor 1,117 SF 204.474.2000 www.shindico.com FOR LEASE Lakeview Square, 175-185 Carlton Street, Winnipeg, Manitoba SURROUNDED BY NUMEROUS AMENITIES Lakeview Square is ideally located at the corner of Carlton Street and St. -

Authority: Planning and Growth Management Committee Item 22.3, Adopted As Amended, by City of Toronto Council on April 3 and 4, 2013

Authority: Planning and Growth Management Committee Item 22.3, adopted as amended, by City of Toronto Council on April 3 and 4, 2013 CITY OF TORONTO BY-LAW No. 468-2013 To adopt Amendment No. 199 to the Official Plan of the City of Toronto with respect to the Public Realm and Heritage Policies. Whereas authority is given to Council under the Planning Act, R.S.O. 1990, c.P. 13, as amended, to pass this By-law; and Whereas Council of the City of Toronto has provided information to the public, held a public meeting in accordance with Section 17 of the Planning Act and held a special public meeting in accordance with the requirements of Section 26 the Planning Act; The Council of the City of Toronto enacts: 1. The attached Amendment No. 199 to the Official Plan of the City of Toronto is hereby adopted. Enacted and passed on April 4, 2013. Frances Nunziata, Ulli S. Watkiss, Speaker City Clerk (Seal of the City) 2 City of Toronto By-law No. 468-2013 AMENDMENT NO. 199 TO THE OFFICIAL PLAN OF THE CITY OF TORONTO The following text and schedule constitute Amendment No. 199 to the Official Plan for the City of Toronto: 1. Section 3.1.1, The Public Realm, is amended by deleting policy 9, substituting therefore the following policies 9, 10 and 11 and renumbering existing policies 10 to 18 inclusive, accordingly: 9. Views from the public realm to prominent buildings, structures, landscapes and natural features are an important part of the form and image of the City. -

Public Art Master Plan

Tuesday July 3, 2018 Final Report Approved Town of Halton Hills PUBLIC ART MASTER PLAN The Planning Partnership Jane Perdue, Public Art Consultant Town of Halton Hills PUBLIC ART MASTER PLAN The Halton Hills Public Art Master Plan was prepared in collaboration with a very dedicated Public Art Advisory Board who provided valuable insight that helped shape the Plan. Members of the Board are: • Catherine McLeod (Chair), Town of Halton Hills • Jamie Smith, Town of Halton Hills • Judy Daley, Town of Halton Hills • Chris Macewan • Christy Michalak • Sheri Tenaglia • Tracey Hagyard Table of Contents 01 Introduction 02 What is a Public Art Master Plan? 02 02 Public Art 03 What is Public Art? 03 Who is an Artist? 03 Role of Public Art 05 Types of Public Art 07 03 Study Process & Community Engagement 09 Study Process 09 Community Engagement 10 What We Heard 11 04 Study Area 13 05 Review of Background Reports & Policy 15 06 Existing Public Art in Halton Hills 21 07 Vision & Guiding Principles 25 08 Site Selection Criteria 27 Locations for Public Art 27 Criteria for all Locations 27 09 Site Locations for Public Art 29 Public and Cultural Facilities 31 Parks and Open Spaces 33 Trails 35 Gateways and Corridors 37 Capital Projects and Studies 39 10 Site Locations for Public Art in Focus Areas 41 Acton 41 Georgetown 43 Glen Williams 45 Limehouse 47 Norval 49 11 Considerations in Identifying Priorities 51 12 Art Acquisition and Commissioning Methods 53 Town-initiated Commissioning 55 Private Developer Commissions 57 Community-based Initiatives 57 Temporary