Does the Presence of Privacy and Security Relevant

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Android Devices

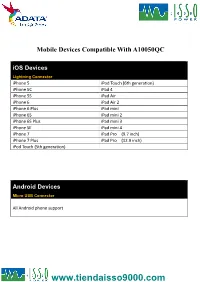

Mobile Devices Compatible With A10050QC iOS Devices Lightning Connector iPhone 5 iPod Touch (6th generation) iPhone 5C iPad 4 iPhone 5S iPad Air iPhone 6 iPad Air 2 iPhone 6 Plus iPad mini iPhone 6S iPad mini 2 iPhone 6S Plus iPad mini 3 iPhone SE iPad mini 4 iPhone 7 iPad Pro (9.7 inch) iPhone 7 Plus iPad Pro (12.9 inch) iPod Touch (5th generation) Android Devices Micro USB Connector All Android phone support Smartphone With Quick Charge 3.0 Technology Type-C Connector Asus ZenFone 3 LG V20 TCL Idol 4S Asus ZenFone 3 Deluxe NuAns NEO VIVO Xplay6 Asus ZenFone 3 Ultra Nubia Z11 Max Wiley Fox Swift 2 Alcatel Idol 4 Nubia Z11miniS Xiaomi Mi 5 Alcatel Idol 4S Nubia Z11 Xiaomi Mi 5s General Mobile GM5+ Qiku Q5 Xiaomi Mi 5s Plus HP Elite x3 Qiku Q5 Plus Xiaomi Mi Note 2 LeEco Le MAX 2 Smartisan M1 Xiaomi MIX LeEco (LeTV) Le MAX Pro Smartisan M1L ZTE Axon 7 Max LeEco Le Pro 3 Sony Xperia XZ ZTE Axon 7 Lenovo ZUK Z2 Pro TCL Idol 4-Pro Smartphone With Quick Charge 3.0 Technology Micro USB Connector HTC One A9 Vodafone Smart platinum 7 Qiku N45 Wiley Fox Swift Sugar F7 Xiaomi Mi Max Compatible With Quick Charge 3.0 Technology Micro USB Connector Asus Zenfone 2 New Moto X by Motorola Sony Xperia Z4 BlackBerry Priv Nextbit Robin Sony Xperia Z4 Tablet Disney Mobile on docomo Panasonic CM-1 Sony Xperia Z5 Droid Turbo by Motorola Ramos Mos1 Sony Xperia Z5 Compact Eben 8848 Samsung Galaxy A8 Sony Xperia Z5 Premium (KDDI Japan) EE 4GEE WiFi (MiFi) Samsung Galaxy Note 4 Vertu Signature Touch Fujitsu Arrows Samsung Galaxy Note 5 Vestel Venus V3 5070 Fujitsu -

Program Analysis Based Approaches to Ensure Security and Safety of Emerging Software Platforms

Program Analysis Based Approaches to Ensure Security and Safety of Emerging Software Platforms by Yunhan Jia A dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy (Computer Science and Engineering) in The University of Michigan 2018 Doctoral Committee: Professor Z. Morley Mao, Chair Professor Atul Prakash Assistant Professor Zhiyun Qian, University of California Riverside Assistant Professor Florian Schaub Yunhan Jia [email protected] ORCID iD: 0000-0003-2809-5534 c Yunhan Jia 2018 All Rights Reserved To my parents, my grandparents and Xiyu ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS Five years have passed since I moved into the Northwood cabin in Ann Arbor to chase my dream of obtaining a Ph.D. degree. Now, looking back from the end of this road, there are so many people I would like to thank, who are an indispensable part of this wonderful journey full of passion, love, learning, and growth. Foremost, I would like to gratefully thank my advisor, Professor Zhuoqing Morley Mao for believing and investing in me. Her constant support was a definite factor in bringing this dissertation to its completion. Whenever I got lost or stucked in my research, she would always keep a clear big picture of things in mind and point me to the right direction. With her guidance and support over these years, I have grown from a rookie to a researcher that can independently conduct research. Besides my advisor, I would like to thank my thesis committee, Professor Atul Prakash, Professor Zhiyun Qian, and Professor Florian Schaub for their insightful suggestions, com- ments, and support. -

Layered Mobile Device Architecture

ISSN (e): 2250 – 3005 || Volume, 08 || Issue,10|| October – 2018 || International Journal of Computational Engineering Research (IJCER) Layered Mobile Device Architecture 1Shinto Kurian 2Dr.K.Nirmala K, Research Scholar(Reg.No:PhD/10/PTE/1/2017, Madras University), Quaid-E-Millath College for Women, Chennai - 600 002, Tamilnadu,India. Assoc. Professor,Dept. of Computer Science, Quaid-E-Millath College for Women, Chennai - 600 002, Tamilnadu,India Corresponding Author: Shinto Kurian ABSTRACT Mobile device structure is organised in a layered architecture from electronic components to application user interface. Based on various functionalities, the mobile devices are separated into multiple layers. Each layer has well defined boundaries and interacts with each other using certain protocols. The layered separation helps the devices to segregate the functionalities in stabilized and secured manner. Depending on manufacture, the components in each layer change. Most of the mobile devices are follow a standard architecture but the components and methodologies used in each layer have differences. The degree of smoothness between the layers directly proportionate with user friendliness of the mobile device. KEYWORDS: Mobile Device, Operating system, Software, Hardware, BIOS, Firmware, User Interface. ----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- ---------- Date of Submission: 15-12-2018 Date of acceptance: 31-12-2018 --------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------- -

RELEASE NOTES UFED PHYSICAL ANALYZER, Version 5.0 | March 2016 UFED LOGICAL ANALYZER

NOW SUPPORTING 19,203 DEVICE PROFILES +1,528 APP VERSIONS UFED TOUCH, UFED 4PC, RELEASE NOTES UFED PHYSICAL ANALYZER, Version 5.0 | March 2016 UFED LOGICAL ANALYZER COMMON/KNOWN HIGHLIGHTS System Images IMAGE FILTER ◼ Temporary root (ADB) solution for selected Android Focus on the relevant media files and devices running OS 4.3-5.1.1 – this capability enables file get to the evidence you need fast system and physical extraction methods and decoding from devices running OS 4.3-5.1.1 32-bit with ADB enabled. In addition, this capability enables extraction of apps data for logical extraction. This version EXTRACT DATA FROM BLOCKED APPS adds this capability for 110 devices and many more will First in the Industry – Access blocked application data with file be added in coming releases. system extraction ◼ Enhanced physical extraction while bypassing lock of 27 Samsung Android devices with APQ8084 chipset (Snapdragon 805), including Samsung Galaxy Note 4, Note Edge, and Note 4 Duos. This chipset was previously supported with UFED, but due to operating system EXCLUSIVE: UNIFY MULTIPLE EXTRACTIONS changes, this capability was temporarily unavailable. In the world of devices, operating system changes Merge multiple extractions in single unified report for more frequently, and thus, influence our support abilities. efficient investigations As our ongoing effort to continue to provide our customers with technological breakthroughs, Cellebrite Logical 10K items developed a new method to overcome this barrier. Physical 20K items 22K items ◼ File system and logical extraction and decoding support for iPhone SE Samsung Galaxy S7 and LG G5 devices. File System 15K items ◼ Physical extraction and decoding support for a new family of TomTom devices (including Go 1000 Point Trading, 4CQ01 Go 2505 Mm, 4CT50, 4CR52 Go Live 1015 and 4CS03 Go 2405). -

Claudia Tapia, Director IPR Policy at the Ericsson

DT: a new technological and economic paradigm Dr Claudia Tapia, Director IPR Policy All views expressed in this speech are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Ericsson Ericsson at a glance NETWORKS IT MEDIA INDUSTRIES Create one network for Transform IT to accelerate Delight the TV Connect industries to a million different needs business agility consumer every day accelerate performance Worldwide mobile 42,000 Patents 40% traffic provided by 222,6 B. SEK Net Sales our networks R&D Employees Licensing Countries with 23,700 >100 agreements 180 customers Average p.a. Licensing revenues Employees 5 B. usd in R&D 10 b. Sek 111,000 Page 2 415,000,000,000 Page 3 STANDARDISATION PROCESS Early Technical Unapproved contribution investment (described in R&D in a patent) Adopted by Standard FRAND CONSENSUS in essential commitment standard patent Return on Access to the investment standard Interoperable high performance devices at a FRAND = Fair, Reasonable and Non- reasonable price DiscriminatoryPage 4 (terms and conditions) 4,000,000,000,000 Page 5 3,452,040 Page 6 3G and LTE (3GPP - 1999 – Dec. 2014 ) 262,773 Submitted contributions 43,917 Approved contributions (16,7%) Source: Signals Research Group. The Essentials of IP, from 3G through LTE Release 12, May 2015 Page 7 LTE approved Contributions for 13 WGs (2009 - Q3 2015) –Source: ABI Research COMPANY RANK Ericsson 1 Huawei 2 Nokia Networks 3 Qualcomm 4 ALU 5 ZTE 6 Samsung 7 Anritsu 8 Rohde & Schwarz 9 CATT 10 Page 8 Principles of standardisation CONSENSUS TRANSPARENCY IMPARTIALITY OPENNESS .. -

The Nanyan Observer No

Published by: Best Ten Campus Media Nanyan News Agency, Shenzhen Graduate School in Guangdong Province Four Pages PEKING UNIVERSITY The Nanyan Observer No. CUMU092017 Monday, 5 December. 2016 General Director: Megan Mancenido Chief Editor: Karras Lambert Managing Editor: Longjun Qin Tel: 0755-26032131 Info: [email protected] PKU Holds 8th Annual Thanksgiving Celebration comes to campus once a year. Min from the neighboring Tsinghua Macarena. Table of Contents University Graduate School. After After several weeks of groundwork a brief introduction, they invited As the Thanksgiving event's PKU Celebrates Thanksgiving..... and coordination between various the School of Transnational Law’s planning assistant, Yang Wandong schools, offices, and volunteers, Assistant Dean Christian Pangilinan of the School of Urban Planning .................................................A1 the much anticipated day had onto the stage to kick the night off Design says it was "awesome to Shenzhen Runner's Guide........... finally arrived. The Chancellor’s with the annual Thanksgiving toast. see things come together in its .................................................A2 Secretariat Office held the 8th Once again, the dinner’s turkeys own way, with everyone's effort, Annual Thanksgiving Celebration were catered by Metro in European then finally take shape in an event Financial Journalism Program...... in B-building's Moot Court. What Town, the side dishes were prepared that people enjoyed. That sense .................................................A3 originally started out as a modest by Frankie’s American Bar & Grille in of accomplishment is what made it All You Need is Ecuador............... get together to share an American Nanshan, and the peach and cherry worthwhile." tradition with Chinese friends cobblers from Baeckerei Thomas in .................................................A4 and colleagues has, over the Shekou. -

携手新时代 共赢创未来 Innovating and Collaborating for What’S Next

携手新时代 共赢创未来 Innovating and collaborating for what’s next Qualcomm中国技术与合作峰会 Qualcomm Technology Day January 25, 2018 #Qualcomm中国技术与合作峰会# Beijing, China Welcome Frank Meng Chairman Qualcomm International, Inc. China January 25, 2018 #Qualcomm中国技术与合作峰会# Beijing, China The opportunity ahead Steve Mollenkopf CEO Qualcomm Incorporated Years of driving the 30+ evolution of wireless Fabless # semiconductor 1 company ~8.6 Billion Cumulative smartphone unit shipments forecast between 2017–2021 Source: Gartner, Sep. ‘17 Mobile technology is powering the 5G global economy The mobile roadmap is leading the way Qualcomm is the R&D engine A strategy for continued growth $20B — RF-Front End Extending the reach of mobile technology $77B — Adjacent industries Core mobile — $32B ~$150B Datacenter — $19B Serviceable addressable Automotive IoT and security opportunity in 2020 $16B $43B Mobile compute Networking $7B $11B Source: combination of third party and internal estimates. Includes SAM for pending NXP acquisition. Note: SAM excludes QTL. Executing on our strategy Automotive IoT and security >$3 Billion in FY17 QCT revenues Up >75% over FY15 Mobile compute Networking FY17 revenue across auto, IoT, security, networking and mobile compute A proven business model that has enabled value creation between China and US Invent Share Collaborate Our commitment to China Supporting growth across many industries China Mobile Semiconductors Automotive China Telecom SMIC | SJ Semiconductor Geely | BYD | ZongMu China Unicom Corp. Huaqin Longcheer IoT Mobile WingTech -

Qualcomm Snapdragon Tech Summit 2019: Partner Quote Sheet

Qualcomm Snapdragon Tech Summit 2019: Partner Quote Sheet Day 1 - Tuesday, December 3, 2019 AT&T: “Together AT&T and Qualcomm Technologies continue to drive the industry forward to unleash the power of the next generation of wireless connectivity over 5G,” said Kevin Petersen, senior vice president AT&T Mobility. “We worked closely with Qualcomm Technologies to be the first to introduce the U.S. to millimeter wave 5G last year, and we’re working together now to begin offering consumers and businesses the latest low-band 5G smartphone technology.” HMD Global: “Our highest priority for 2020 is making 5G more accessible – bringing an affordable yet premium grade, future proof 5G experience for the best possible performance in NSA and SA networks with the Snapdragon 765 Mobile Platform,” said Juho Sarvikas, chief product officer, HMD Global. “Aside from being an excellent mobile platform for best-in-class 5G connectivity, Snapdragon 765 mobile platform allows us to offer breakthrough entertainment capabilities combined with our PureDisplay technology, and our unique ZEISS powered imaging solutions that enable fans to create and share amazing content over 5G. We also congratulate Qualcomm Technologies on the announcement of its Snapdragon Modular Platform. This innovative approach to making 5G more accessible to OEMs will dramatically streamline the development process and we look forward to exploring possibilities of working with Qualcomm Technologies on this exciting platform.” Motorola: “5G is a focus for the entire Lenovo organization - from network infrastructure to personal devices, being the first to launch a 5G smartphone and preview a 5G PC,” said Sergio Buniac, president, Motorola. -

The Impact of COVID-19 on Homeware in China

The Impact of COVID-19 on Homeware in China skinny Key Observations HOME GOODS IN CHINA TODAY • New trends have emerged due to changing consumer behaviour – the crisis has impacted people's attitudes towards food, fitness, education, health and general wellbeing, among others. • Shifts in the homeware industry – it is likely that short-term measures taken in response to coronavirus lead to changes that last for decades. • The homebody economy has reached a wider population across China – since people were forced to stay indoors with the quarantine, a growing number of consumers shopped, studied, worked and amused themselves online at home, creating new consumption habits moving forward. • eCommerce penetration and usage has grown significantly during COVID-19 – the initial lockdown and social distancing provides limited alternatives as many consumers still see the risk in public shopping malls and other brick-and-mortar retailers. • Consumers are increasingly devoting more time to home improvement – there is noticable growth in home accessories, especially food production equipment, sporting goods and soft furnishings. • Current consumption of art suggests healthy growth moving forward – more galleries will utilize third-party online art sales platforms to reach a wider community of collectors. Trending Keywords FEBRUARY – APRIL 2020 KEYWORD(S) INTERPRETATION TAKEAWAY • While traditional homeware suffers a 2.2% YOY decrease in retail sales, the concept of ‘smart households’ is steadily growing in China. Convenience is ideal for busy urbanites when choosing homewares Smart Home • In April this year, a domestic electronics/appliance brand Xiaomi and a contributing factor to the rise of home automation and smart celebrated its 10-year anniversary with a shopping festival that generated homes. -

Qualcomm® Quick Charge™ Technology Device List

One charging solution is all you need. Waiting for your phone to charge is a thing of the past. Quick Charge technology is ® designed to deliver lightning-fast charging Qualcomm in phones and smart devices featuring Qualcomm® Snapdragon™ mobile platforms ™ and processors, giving you the power—and Quick Charge the time—to do more. Technology TABLE OF CONTENTS Quick Charge 5 Device List Quick Charge 4/4+ Quick Charge 3.0/3+ Updated 09/2021 Quick Charge 2.0 Other Quick Charge Devices Qualcomm Quick Charge and Qualcomm Snapdragon are products of Qualcomm Technologies, Inc. and/or its subsidiaries. Devices • RedMagic 6 • RedMagic 6Pro Chargers • Baseus wall charger (CCGAN100) Controllers* Cypress • CCG3PA-NFET Injoinic-Technology Co Ltd • IP2726S Ismartware • SW2303 Leadtrend • LD6612 Sonix Technology • SNPD1683FJG To learn more visit www.qualcomm.com/quickcharge *Manufacturers may configure power controllers to support Quick Charge 5 with backwards compatibility. Power controllers have been certified by UL and/or Granite River Labs (GRL) to meet compatibility and interoperability requirements. These devices contain the hardware necessary to achieve Quick Charge 5. It is at the device manufacturer’s discretion to fully enable this feature. A Quick Charge 5 certified power adapter is required. Different Quick Charge 5 implementations may result in different charging times. Devices • AGM X3 • Redmi K20 Pro • ASUS ZenFone 6* • Redmi Note 7* • Black Shark 2 • Redmi Note 7 Pro* • BQ Aquaris X2 • Redmi Note 9 Pro • BQ Aquaris X2 Pro • Samsung Galaxy -

A Hybrid Interface Recovery Method for Android Kernels Fuzzing335

2020 IEEE 20th International Conference on Software Quality, Reliability and Security (QRS) A Hybrid Interface Recovery Method for Android Kernels Fuzzing Shuaibing Lu, Xiaohui Kuang, Yuanping Nie, Zhechao Lin National Key Laboratory of Science and Technology on Information System Security, Beijing, 100101, China [email protected], xiaohui [email protected], [email protected], [email protected] Abstract—Android kernel fuzzing is a research area of interest considered on two levels: userspace application and kernel. specifically for detecting kernel vulnerabilities which may allow Kernel vulnerabilities threaten operation systems and user attackers to obtain the root privilege. The number of Android applications. The kernel of the Android operating system is mobile phones is increasing rapidly with the explosive growth of Android kernel drivers. Interface aware fuzzing is an effective relatively vulnerable to attack, despite available protections technique to test the security of kernel driver. Existing researches [2]. rely on static analysis with kernel source code. However, in Fuzzing is a well-known technique that is used for security fact, there exist millions of Android mobile phones without testing by generating massive, specially designed inputs to public accessible source code. In this paper, we propose a hybrid the target programs. However, with the Android operating interface recovery method for fuzzing kernels which can recover kernel driver interface no matter the source code is available system becoming more and more complex, kernel interface or not. In white box condition, we employ a dynamic interface arguments are diverse. Without prior knowledge of argument recover method that can automatically and completely identify structures, it is difficult for fuzzing tools to find kernel the interface knowledge. -

DAIICHI 846 263.Xlsx

No. Equipment models/ Brand system version 1 APPLE iPhone 6s (A1700) 2 SAMSUNG S8+ 3 SONY xperia z3 compact 4 LG NEXUS4 5 LG NEXUS5 6 SONY XPERIA XA ULTRA 7 APPLE iPhone 6P(A1524) 8 NOKIA Nokia3 9 MOTOLOLA NEXUS6 10 APPLE iPhone 8 11 APPLE iPhone 6(A1589) 12 APPLE iPhone 5s 13 LG v20 15 HUAWEI NEXUS6P 16 APPLE iPhone7 17 APPLE iPhoneSE 18 APPLE iPhone 6s plus 19 HUAWEI P20 lite 20 GOOGLE pixel 21 GOOGLE pixel2 22 HTC D610T 23 ipod touch A1509 24 HUAWEI 6X 25 APPLE A1431 26 HUAWEI Mate 8(HUAWEI NXT-AL10) 27 LG LG-H791(nexus5X) 28 HUAWEI MHA-AL00(Mate 9) 29 ZTE BA520 30 OPPO A31t 31 LENOVO A320t 32 OPPO A33 34 VIVO Y51A 35 Coolpad Coolpad 8737 36 SAMSUNG SM-G3509 37 VIVO Y31 38 XIAOMI Redmi Note 4X 39 HUAWEI FRD-DL00 40 SAMSUNG Galaxy S7 41 APPLE Iphone 6(64G) 42 APPLE Iphone SE(64G) 43 HUAWEI WAS-AL00 44 HUAWEI H60-L01(Honor6) 45 HUAWEI C8817D(Honor4) 46 vivo Y937 47 SONY Xperia Z3(L55u) 48 APPLE A1529 49 XIAOMI Redmi note2 50 SAMSUNG SM-G9008W 51 Smartisan YQ601 52 SAMSUNG S6(SM-G9250) 53 SAMSUNG S6(SM-G920P) 54 HUAWEI HUAWEI G750-T00 55 SAMSUNG SM-N9008 56 NOKIA 1520 58 HUAWEI P7-L00 59 ZTE ZTE S2002 60 SAMSUNG SM-N7506V 61 HTC HTC M8St 62 HUAWEI Honor X1(7D-503L) 63 LG Nexus 5 64 SAMSUNG GT-I9300 65 APPLE iphone5 66 HUAWEI Honor 7i (ATH-AL00) 67 MEIZU note2 68 HUAWEI Mate7-TL00 69 Leshi Letv X800+ 70 KONKA L550 71 Hisense H910 72 XIAOMI Mi 4(2G) 73 OPPO OPPO X9007 74 HONOR H30-T00 75 VIVO vivo X3S W 76 SAMSUNG SPH-D710 77 SAMSUNG SM-G3818 78 SAMSUNG GT-I8552 79 HTC HTC Z520 80 SAMSUNG I997 81 SAMSUNG 9100 82 SAMSUNG I9500 83 MEIZU MXM032