“As We Are Both Deceived”: Strategies of Status Repair in 19Thc Hudson's

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

NWC-3361 Cover Layout2.Qx

2 0 0 1 A N N U A L R E P O R T vision growth value N O R T H W E S T C O M P A N Y F U N D 2 0 0 1 A N N U A L R E P O R T 2001 financial highlights in thousands of Canadian dollars 2001 2000 1999 Fiscal Year 52 weeks 52 weeks 52 weeks Results for the Year Sales and other revenue $ 704,043 $ 659,032 $ 626,469 Trading profit (earnings before interest, income taxes and amortization) 70,535 63,886 59,956 Earnings 29,015 28,134 27,957 Pre-tax cash flow 56,957 48,844 46,747 Financial Position Total assets $ 432,033 $ 415,965 $ 387,537 Total debt 151,581 175,792 171,475 Total equity 219,524 190,973 169,905 Per Unit ($) Earnings for the year $ 1.95 $ 1.89 $ 1.86 Pre-tax cash flow 3.82 3.28 3.12 Cash distributions paid during the year 1.455 1.44 1.44 Equity 13.61 13.00 11.33 Market price – January 31 17.20 13.00 12.00 – high 17.50 13.00 15.95 – low 12.75 9.80 11.25 Financial Ratios Debt to equity 0.69:1 0.92:1 1.01:1 Return on net assets* 12.7% 11.5% 11.6% Return on average equity 14.9% 15.2% 16.8% *Earnings before interest and income taxes as a percent of average net assets employed All currency figures in this report are in Canadian dollars, unless otherwise noted. -

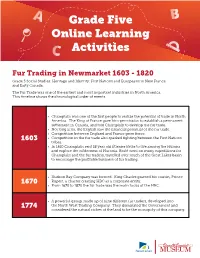

Grade Five Online Learning Activities

Grade Five Online Learning Activities Fur Trading in Newmarket 1603 - 1820 Grade 5 Social Studies: Heritage and Identity: First Nations and Europeans in New France and Early Canada. The Fur Trade was one of the earliest and most important industries in North America. This timeline shows the chronological order of events. • Champlain was one of the first people to realize the potential of trade in North America. The King of France gave him permission to establish a permanent settlement in Canada, and told Champlain to develop the fur trade. • Not long after, the English saw the financial potential of the fur trade. • Competition between England and France grew fierce. 1603 • Competition in the fur trade also sparked fighting between the First Nations tribes. • In 1610 Champlain sent 18 year old Étienne Brulé to live among the Hurons and explore the wilderness of Huronia. Brulé went on many expeditions for Champlain and the fur traders, travelled over much of the Great Lakes basin to encourage the profitable business of fur trading. • Hudson Bay Company was formed. King Charles granted his cousin, Prince 1670 Rupert, a charter creating HBC as a corporate entity. • From 1670 to 1870 the fur trade was the main focus of the HBC. • A powerful group, made up of nine different fur traders, developed into 1774 the North West Trading Company. They dominated the Government and considered the natural riches of the land to be the monopoly of this company. Grade Five Online Learning Activities Fur Trading in Newmarket 1603 - 1820 • Competition and jealousy raged between the North West Company and the 1793 Hudson Bay Company. -

Road to Oregon Written by Dr

The Road to Oregon Written by Dr. Jim Tompkins, a prominent local historian and the descendant of Oregon Trail immigrants, The Road to Oregon is a good primer on the history of the Oregon Trail. Unit I. The Pioneers: 1800-1840 Who Explored the Oregon Trail? The emigrants of the 1840s were not the first to travel the Oregon Trail. The colorful history of our country makes heroes out of the explorers, mountain men, soldiers, and scientists who opened up the West. In 1540 the Spanish explorer Coronado ventured as far north as present-day Kansas, but the inland routes across the plains remained the sole domain of Native Americans until 1804, when Lewis and Clark skirted the edges on their epic journey of discovery to the Pacific Northwest and Zeb Pike explored the "Great American Desert," as the Great Plains were then known. The Lewis and Clark Expedition had a direct influence on the economy of the West even before the explorers had returned to St. Louis. Private John Colter left the expedition on the way home in 1806 to take up the fur trade business. For the next 20 years the likes of Manuel Lisa, Auguste and Pierre Choteau, William Ashley, James Bridger, Kit Carson, Tom Fitzgerald, and William Sublette roamed the West. These part romantic adventurers, part self-made entrepreneurs, part hermits were called mountain men. By 1829, Jedediah Smith knew more about the West than any other person alive. The Americans became involved in the fur trade in 1810 when John Jacob Astor, at the insistence of his friend Thomas Jefferson, founded the Pacific Fur Company in New York. -

Métis History and Experience and Residential Schools in Canada

© 2006 Aboriginal Healing Foundation Published by: Aboriginal Healing Foundation 75 Albert Street, Suite 801, Ottawa, Ontario K1P 5E7 Phone: (613) 237-4441 Toll-free: (888) 725-8886 Fax: (613) 237-4442 E-mail: [email protected] Website: www.ahf.ca Design & Production: Aboriginal Healing Foundation Printed by: Dollco Printing ISBN 1-897285-35-3 Unauthorized use of the name “Aboriginal Healing Foundation” and of the Foundation’s logo is prohibited. Non-commercial reproduction of this document is, however, encouraged. Tis project was funded by the Aboriginal Healing Foundation but the views expressed in this report are the personal views of the author(s). Ce document est aussi disponible en français. Métis History and Experience and Residential Schools in Canada Prepared for Te Aboriginal Healing Foundation by Larry N. Chartrand Tricia E. Logan Judy D. Daniels 2006 Table of Contents INTRODUCTION ......................................................................................................................... 1 MÉTIS RESIDENTIAL SCHOOL PARTICIPATION: A LITERATURE REVIEW ............ 5 Acknowledgements ....................................................................................................................................7 Executive Summary ...................................................................................................................................9 Introduction..............................................................................................................................................11 -

Growing with the North OUR MISSION

1997 ANNUAL REPORT growing with the North OUR MISSION NWC is the leading provider of food and everyday products and services to remote communities across northern Canada and Alaska. Our purpose is to create superior long-term investor value by enhancing our value to our customers, our employees, and the communities we serve. serving remote communities F I N A N C I A L H I G H L I G HTS 53 weeks ended 52 weeks ended 52 weeks ended (in thousands of Canadian dollars) January 31, 1998 January 25, 1997 January 27, 1996 RES ULTS FOR THE YEAR Sales and other revenue $ 616,710 $ 590,583 $ 592,034 Operating profit before provision for loss on disposition 39,587 43,208 32,860 Net earnings (loss) 21,037 17,858 (5,172) Pre-tax cash flow 42,244 44,094 33,321 FINANCIAL POSITION Total assets $ 425,136 $ 383,736 $ 375,947 Total debt 201,408 175,027 178,275 Total equity 160,160 147,353 139,953 PER UNIT / S HARE Fully diluted earnings for the year before provision for loss on disposition $ 1.40 $ 1.18 $ 0.68 Fully diluted earnings (loss) for the year 1.40 1.18 (0.32) Pre-tax cash flow 2.82 2.92 2.08 Cash distributions/dividends paid during the year 0.60 0.40 0.40 Equity 10.68 9.82 9.02 Average units/shares outstanding (# in 000’s) 15,000 15,095 16,040 Units/shares outstanding at year-end (# in 000’s) 15,000 15,000 15,519 1997 highlights FINANCIAL RATIOS Debt to equity 1.26 : 1 1.19 : 1 1.27 : 1 Return on net assets* 11.7% 13.4% 9.8% Return on average equity before provision 13.8% 12.7% 7.0% * Operating profit as a percent of average net assets employed. -

History of North Dakota Chapter 3

34 History of North Dakota CHAPTER 3 A Struggle for the Indian Trade THE D ISCOVERY OF AMERICA set in motion great events. For one thing, it added millions of square miles of land to the territorial resources which Europeans could use. For another, it provided a new source of potential income for the European economy. A golden opportunity was at hand, and the nations of Europe responded by staking out colonial empires. As the wealth of the New World poured in, it brought about a 400-year boom and transformed European institutions. Rivalry for empire brought nations into conflict over the globe. It reached North Dakota when fur traders of three nationalities struggled to control the Upper Missouri country. First the British, coming from Hudson Bay and Montreal, dominated trade with the Knife River villages. Then the Spanish, working out of St. Louis, tried to dislodge the British, but distance and the hostility of Indians along the Missouri A Struggle for the Indian Trade 35 caused them to fail. After the Louisiana Purchase, Lewis and Clark claimed the Upper Missouri for the United States, and Americans from St. Louis began to seek trade there. They encountered the same obstacles which had stopped the Spanish, however, and with the War of 18l 2, they withdrew from North Dakota, leaving it still in British hands. THE ARRIVAL OF BRITISH TRADERS When the British captured Montreal in 1760, the French abandoned their posts in the Indian country and the Indians were compelled to carry all of their furs to Hudson Bay. Before long, however, British traders from both the Bay and Montreal began to venture into the region west of Lake Superior, and by 1780 they had forts on the Assiniboine River. -

Joseph Felix Larocque E

Joseph Félix LaRocque LAROCQUE , JOSEPH (perhaps Joseph-Félix ), Hudson Bay Company chief trader; b. c. 1787; d. 1 Dec. 1866 at Ottawa, Canada West. Joseph Larocque, whose brother François-Antoine was also active in the fur trade, was the son of François-Antoine Larocque, member for the county of Leinster (L’Assomption) in the first parliament of Lower Canada, and Angélique Leroux, and may have been the child, baptized François, born 20 Sept. 1786 at L’Assomption, Province of Quebec. If this identification is accepted, Joseph would have been 15 years old when he was a clerk in the XY Company in 1801. At this time, the XY Company was challenging the dominance of the North West Company. When they settled their differences Joseph Larocque transferred to the NWC and was sent to serve on the upper Churchill (or English) River. He is known to have been at Lake La Ronge in 1804 and at Fort des Prairies in 1806. He was transferred to the Columbia River Department of the North West Company, but no details of his career are known until he appears in 1812 in the neighbourhood of Fort Kamloops (Kamloops, B.C.), among the Shuswap Indians. In 1813 he joined John George McTavish* in his descent of the Columbia River and take-over of Fort Astoria (Astoria, Oreg.) from the Pacific Fur Company. Larocque spent the next three years in the Columbia River Department, travelling much, often with dispatches, and managing posts among the Flatheads and at Okanagan, Fort Kamloops, or Spokane House, until in 1816 he returned over the mountains from Fort George (Astoria, Oreg.) to Fort William (Thunder Bay, Ont.), carrying dispatches. -

Norttiern Stores Department, Hudson's Bay Company, 1959 - T987

AN ARCHIVAL ADMINISTRATTVE HISTORY of the NORTTIERN STORES DEPARTMENT, HUDSON'S BAY COMPANY, 1959 - T987 by GERALDINE ALTON HARRIS A THESIS SUBMITTED TO TTIE FACULTY OF GRADUATE STUDIES IN PARTIAL FULFILLMENT OF THE REQUIREMENTS FOR THE DEGREE OF MASTER OF ARTS Department of History University of Manitoba ÌWinnipeg, Manitoba @ October,1994 Bibliothèque nationale !*il ff$onatt-iorav du Canada Acquisitions and Direction des acquisitions et Bibliographic Services Branch des services bibliograPhiques 395 Weìlington $re€t 395, rue Wellington Ottawa, Onlario Ottawa (Onlario) KIAON4 K1AON4 Yout l¡ls vo\rc élércnce Oû lile Nolrc élèrcnce THE AUTHORHAS GRA}{TED A}I L'AUTEUR A ACCORDE UNE LICENCE IRREVOCABLE NON.EXCLUSIVE IRREVOCABLE ET NON EXCLUSIVE LICENCE ALLOWING THE NATIONAL PERMETTA}IT A LA BIBLIOÏIEQIJE LIBRARY OF CAI.{ADA TO NATIONALE DU CAI.{ADA DE REPRODUCE, LOAI.I, DISTRIBUTE OR REPRODUIRE, PRETER. DISTRIBUER SELL COPIES OF HISÆIER THESIS BY OU VENDRE DES COPIES DE SA A}IY MEA}{S AI.ID IN AI{Y FORM OR TIfrSE DE QIJELQIJE MANIERE ET FORMAT, MAKING THIS THESIS SOUS QIJELQIJE FORME QIJE CE SOIT AVAILABLE TO INTERESTED POUR METTRE DES E)GMPLAIRES DE PERSONS. CETTE TTTESE A LA DISPOSITION DES PERSONNE INTERESSEES. TITE AUTITOR RETAINS OWNERSHIP L'AUTEUR CONSERVE LA PROPRIETE OF THE COPYRIGHT IN HIS/TTER DU DROIT D'AUTEUR QIII PROTEGE TIIESIS. NEITI{ER TI{E TI{ESIS NOR SA THESE. NI LA TIIESE NI DES SUBSTA}{TIAL EXTRACTS FROM IT EXTRAITS SUBSTAI.{TIELS DE CELLE. MAY BE PRINTED OR OTTIERWISE CI NE DOIVENT ETRE IMPRIMES OU REPRODUCED WITHOUT HISÆIER AUTREN4ENT REPRODUITS SA}{S SON PERMISSION. -

North West Company Fund North West Company Fund Annual Meeting of Unitholders Annual Meeting of Unitholders June 5, 2007 June 5

North West Company Fund Annual Meeting of Unitholders June 5, 2007 Winnipeg, Manitoba Speech by Ian Sutherland, Chairman I commented on the impact of the new tax on income trusts in our Annual Report. The price of NWF units has risen back above the level prior to announcement of this tax on October 31, 2006. This investment performance is due, I believe, mostly to superior operating results and the confidence that analysts and investors have in our management and business model. Since the October 31, 2006 tax announcement, the acquisition of Canadian trusts has heated up with most of the acquirers being foreign entities or private equity. Trusts are not alone as a number of public companies are also being acquired. Our large Canadian pension plans have been attracted to the high returns of private equity in comparison to public equities. A significant part of these higher returns is the tax savings realized by increased debt costs of LBO’s and the ownership through non taxable private partnerships. While the intent of the Tax Fairness legislation in leveling the playing field and broadening the tax base was laudable, the result is the reverse. The tax base will shrink as companies and trusts are privatized or acquired by foreign entities. Taxable Canadian public companies will be at a great disadvantage and our public capital markets will shrink. The enhanced dividend tax credit eliminated most of the double tax on company shares and trust units held by taxable accounts. What is required is a similar tax credit for RSP’s, pension funds and other Canadian tax exempt or deferred accounts. -

Grand Portage As a Trading Post: Patterns of Trade at "The Great Carrying Place"

Grand Portage as a Trading Post: Patterns of Trade at “the Great Carrying Place” By Bruce M. White Turnstone Historical Research St. Paul, Minnesota Grand Portage National Monument National Park Service Grand Marais, Minnesota September 2005 On the cover: a page from an agreement signed between the North West Company and the Grand Portage area Ojibwe band leaders in 1798. This agreement is the first known documentary source in which multiple Grand Portage band leaders are identified. It is the earliest known documentation that they agreed to anything with a non-Native entity. Contents List of Tables ..................................................................................................................... ii List of Illustrations ............................................................................................................. ii Preface ............................................................................................................................... iii Introduction .........................................................................................................................1 Trade Patterns .....................................................................................................................5 The Invention of the Great Lakes Fur Trade ....................................................................13 Ceremonies of Trade, Trade of Ceremonies .....................................................................19 The Wintering Trade .........................................................................................................27 -

Introduction Section

INTRODUCTION 58 2.5 The Fur Trade along the Ottawa River Through the 17th century, an almost endless stream of men plied the Ottawa River on long and dangerous fur‐gathering expeditions. Their contribution to the fur trade was critical to the survival of New France. The Ottawa River was a route of choice for travel to fur‐harvesting areas, and was considered simply to be an extension of the St. Lawrence. The story of the fur trade along the Ottawa River can and should be told from at least two perspectives: that of the Europeans who crossed the ocean to a foreign land, taking great personal risks in pursuit of adventure and profit, and that of the First Nations Peoples who had been living in the land and using its waterways as trade conduits for several thousand years. The very term “fur trade” only refers to half of this complex relationship. From a European perspective, there was a “fur trade,” since animal (primarily beaver) pelts were the commodity in demand. First Nations groups, on the other hand, were engaged in a trade for needles, thread, clothing, fishing hooks, axes, kettles, steel strike‐a‐lights, glass beads, alcohol, and other goods, mainly utilitarian items of metal (Kennedy 88). A more balanced account of the fur trade10 along the Ottawa River begins with the context in which both trading parties chose to engage in an exchange of goods. 2.5.1 European Demand Change in the Ottawa River region in the 17th and 18th centuries was shaped in large part by European demand for beaver pelts. -

NATIVE AMERICAN in the LAND of the SHOGUN Ranald Macdonald and the Opening of Japan by Frederik L

WashingtonHistory.org NATIVE AMERICAN IN THE LAND OF THE SHOGUN Ranald MacDonald and the Opening of Japan By Frederik L. Schodt COLUMBIA The Magazine of Northwest History, Fall 2005: Vol. 19, No. 3 One of the most imposing landmarks in the city of Astoria is the Astoria Column, towering dramatically atop Coxcomb Hill, overlooking the Columbia River. A tourist pamphlet declares that the column, built in 1926, "commemorates the westward sweep of discovery and migration which brought settlement and western civilization to the Northwest Territory." This "westward sweep" nearly swept away all indigenous cultures in its path, but in 1961, at the foot of the tower, in what almost seems to have been an afterthought, the city added a small memorial to Chief Comcomly of the Chinooks. It is a raised black burial canoe, rendered in concrete, minus his remains. Directly below the hill and monument, on the corner of 15th and Exchange Streets, is a small park featuring a partial reconstruction of the original Fort Astoria, with part of a blockhouse and palisade visible. In one corner stands a granite stone memorial to Comcomly's descendant, Ranald MacDonald. Dedicated on May 21, 1988, with funding provided by the Portland Japanese Chamber of Commerce and generous individuals, the MacDonald monument has an inscription in English on one side and in Japanese on the other. The English engraving reads: Birthplace of Ranald MacDonald, 1824-1894. First teacher of English in Japan. The son of the Hudson's Bay Co. manager of Ft. George and Chinook chief Comcomly's daughter, MacDonald theorized that a racial link existed between Indians and Japanese.