George Riddoch: the Man Who Found Ludwig Guttmann

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society

Sources for Epsom & Ewell History Proceedings of the Leatherhead & District Local History Society The Leatherhead & District Local History Society was formed in 1946 for everyone interested in the history of the area including Ashtead, Bookham, Fetcham and Headley as well as Leatherhead. Since their foundation, they have been publishing an annual volume of Proceedings in a series which is currently in its seventh volume. Coming from an area that borders on Epsom, these Proceedings contain a great deal of material relating to our area and the following list which gives relevant articles and page references. The Society has its headquarters at the Leatherhead Museum, 64 Church Street, KT22 8DP. The Museum ([email protected]) is the best place to contact for their collection of records, which are in four series: original material (X), transcripts (W), photographs (P) and maps (M). The Society They meet for talks on the third Friday of the months from September to May meet at the Letherhead Institute at the top of Leatherhead High Street. For more details, see http://www.leatherheadlocalhistory.org.uk/. A.J. Ginger, ‘Fetcham in Victorian times: II’, Proc. of the LDLHS 1 (1947–56) iii pp14– 18. p16, memories of Happy Jack the tramp, and a case at Epsom Police Court. A.J. Ginger, ‘Leatherhead in Victorian times’, Proc. of the LDLHS 1 (1947–56) vii pp12– 18. p16, memories of Derby week. F. Bastian, ‘Leatherhead families of the 16th and 17th centuries: I, the Skeete family’, Proc. of the LDLHS 2 (1957–66) pp6–14. pp11–13, Edward Skeete moved to Ewell in the 1610s, and the family were yeomen and millers here for the next 50 years; they may be related to the Skeets of Barbados. -

Built up Areas Character Appraisal Ashtead

Supplementary Planning Document Built Up Areas Character Appraisal Ashtead Adopted 23 February 2010 Mole Valley Local Development Framework 2 Built up Areas Character Appraisal – Ashtead Contents 1.0 Background ................................................................................................3 2.0 Methodology ...............................................................................................3 3.0 Policy Context .............................................................................................4 4.0 Ashtead Overview .......................................................................................5 5.0 Landscape Setting ......................................................................................6 6.0 The Village...................................................................................................6 7.0 Woodfield ....................................................................................................8 8.0 Oakfield Road to The Marld ........................................................................9 9.0 South Ashtead ............................................................................................9 10.0 West Ashtead ...........................................................................................11 11.0 West North Ashtead ..................................................................................12 12.0 The Lanes .................................................................................................13 13.0 North East Ashtead -

21 Bus Time Schedule & Line Route

21 bus time schedule & line map 21 Crawley - Dorking - Leatherhead - Epsom View In Website Mode The 21 bus line (Crawley - Dorking - Leatherhead - Epsom) has 4 routes. For regular weekdays, their operation hours are: (1) Box Hill: 7:08 PM (2) Crawley: 6:51 AM - 5:15 PM (3) Epsom: 6:20 AM - 2:46 PM (4) Leatherhead: 5:30 PM Use the Moovit App to ƒnd the closest 21 bus station near you and ƒnd out when is the next 21 bus arriving. Direction: Box Hill 21 bus Time Schedule 19 stops Box Hill Route Timetable: VIEW LINE SCHEDULE Sunday Not Operational Monday 7:08 PM Leatherhead Railway Station (T) Station Approach, Leatherhead Tuesday 7:08 PM Leret Way, Leatherhead Wednesday 7:08 PM Leret Way, Leatherhead Thursday 7:08 PM The Crescent, Leatherhead Friday 7:08 PM Russell Court, Leatherhead Saturday Not Operational Highlands Road, Leatherhead Seeability, Leatherhead Lavender Close, Leatherhead 21 bus Info Clinton Road, Leatherhead Direction: Box Hill Stops: 19 Glenheadon Rise, Leatherhead Trip Duration: 27 min Line Summary: Leatherhead Railway Station (T), Tyrrells Wood, Leatherhead Leret Way, Leatherhead, The Crescent, Leatherhead, Highlands Road, Leatherhead, Seeability, Headley Court, Headley Leatherhead, Clinton Road, Leatherhead, Glenheadon Rise, Leatherhead, Tyrrells Wood, Hurst Lane, Headley Leatherhead, Headley Court, Headley, Hurst Lane, Headley, The Cock Inn, Headley, Broome Close, The Cock Inn, Headley Headley, Crossroads, Headley, Headley Common Road, Headley, Headley Common Road, Broome Close, Headley Pebblecombe, The Tree, Box Hill, -

For Sale, to Let

hurstwarne.co.uk FOR SALE, TO LET Preliminary Details Aldershot - Warehouse & Industrial, Investment Property 55,000 sq ft (5,109.67 sq m) GIA Sunbury House, Christy Estate, Aldershot, Hampshire, GU12 4TX For viewing and further information contact: Peter Richards Key Benefits 01483 723344 Yard area 07803 078011 [email protected] Eaves in main warehouse minimum 6.2m, rising to 8m Steve Barrett Good parking 01252 816061 Air conditioning in parts 07894 899728 Own substation [email protected] Staff breakout room Farnborough 01252 816061 Woking 01483 723344 Guildford 01483 388800 Leatherhead 01372 360190 Redhill 01737 852222 Agency • Investment • Development • Asset Management • Landlord & Tenant Sunbury House, Christy Estate, Aldershot, Hampshire, GU12 4TX Location Energy Performance Rating The premises are located in Ivy Road forming part of the Christy Estate in North A copy of the Energy Performance Certificate is Town, Aldershot. This is the principle industrial area in the town with good available on request from the agents. access to the A331 Blackwater Valley Relief Road which links to the M3 at junction 4. Business Rates Description Rates Payable: £113,883 per annum (based upon Rateable Value: £231,000 and UBR: 49.3p) The premises comprise a purpose built, early 1980’s, detached industrial/warehouse unit of double span steel portal frame construction with two Interested parties should make their own enquiries with the floors of offices to the front elevation. relevant local authority. There are three loading doors in total, two of which are situated on the eastern elevation of the property and the other loading door is part of the new warehouse Service Charge extension. -

Elmbridge Borough Council Green Belt Boundary Review Annex Report 2 - Local Area Assessment Pro-Formas

Elmbridge Borough Council Green Belt Boundary Review Annex Report 2 - Local Area Assessment Pro-formas Issue Rev C | 14 March 2016 This report takes into account the particular instructions and requirements of our client. It is not intended for and should not be relied upon by any third party and no responsibility is undertaken to any third party. Job number 243074-00 Ove Arup & Partners Ltd 13 Fitzroy Street London W1T 4BQ United Kingdom www.arup.com Local Area 1 Area (ha) 453.1 Location Plan Strategic Area Strategic Area C lies on the fringes of a much wider area of strategic Green Belt which extends Summary across much of Surrey. Its strategic role in Elmbridge is to prevent the town of Oxshott / Cobham from merging with Ashtead and Leatherhead / Bookham / Fetcham in Mole Valley, though it is also important for preventing encroachment into open countryside. Much of the Area retains an unspoilt and open, rural character, though in some isolated localities ribbon development along roads and the loss of arable farmland to horse paddocks has diminished this character somewhat. At the strategic level, the Strategic Area plays an important role in meeting the fundamental aim of Green Belt policy to prevent urban sprawl by keeping land permanently open. Assessment of the Strategic Area against the relevant NPPF Purposes is as follows: - Purpose 1 – Meets the Purpose moderately by acting as an important barrier to potential sprawl from the Guildford urban area, Ash and Tongham urban area, Dorking, and Leatherhead / Bookham / Fetcham / Ashtead. - Purpose 2 – Meets the Purpose strongly by establishing important gaps between a number of Surrey towns from merging into one another. -

465 Dorking – Leatherhead

465 Dorking–Leatherhead–Kingston 465 Mondays to Fridays DorkingTownfieldCourt 0515 0544 0610 0632 0651 0717 0745 0815 0846 0917 0947 1017 1047 1102 1132 1202 1232 1302 1322 DorkingStation 0519 0548 0615 0637 0658 0726 0754 0824 0855 0926 0956 1026 1056 1111 1141 1211 1241 1311 1331 MicklehamChurch 0525 0554 0621 0643 0704 0732 0801 0831 0902 0932 1002 1032 1102 1117 1147 1217 1247 1317 1337 LeatherheadLeisureCentre 0532 0601 0628 0650 0713 0741 0811 0841 0911 0941 1011 1041 1111 1126 1156 1226 1256 1326 1346 LeatherheadNorthStreet 0534 0603 0630 0652 0716 0744 0814 0844 0914 0944 1014 1044 1114 1129 1159 1229 1259 1329 1349 LeatherheadCommonOxshottRoad 0540 0609 0636 0700 0727 0755 0825 0854 0922 0952 1022 1052 1122 1137 1207 1237 1307 1337 1357 MaldenRushettTheShyHorse 0544 0614 0642 0709 0736 0805 0835 0903 0930 0958 1028 1058 1128 1143 1213 1243 1313 1343 1403 ChessingtonWorldofAdventures 0547 0617 0646 0713 0741 0810 0840 0908 0935 1003 1033 1103 1133 1148 1218 1248 1318 1348 1408 HookRoadHolmwoodRoad 0552 0622 0652 0720 0749 0819 0849 0916 0943 1011 1041 1110 1140 1155 1225 1255 1325 1355 1415 HookCapinHand 0555 0625 0655 0725 0755 0825 0854 0920 0946 1014 1044 1113 1143 1158 1228 1258 1328 1358 1418 SurbitonStationClaremontRoad 0602 0632 0703 0734 0805 0835 0903 0929 0955 1023 1053 1122 1152 1207 1237 1307 1337 1407 1427 KingstonEdenStreet 0608 0639 0711 0742 0814 0844 0912 0938 1004 1032 1102 1131 1201 1216 1246 1316 1346 1416 1436 KingstonCromwellRoadBusStation 0610 0641 0714 0745 0817 0847 0915 0941 1007 1035 1105 1134 1204 1219 -

Airport Surface Access Strategy 2012-2017

Airport Surface Access Strategy 2012-2017 Contents 1 Introduction 4 APPENDIX A – LOCAL PUBLIC TRANSPORT SERVICES 36 2 Vision 6 APPENDIX B – TRAFFIC FLOWS 40 3 Policy Context 8 APPENDIX C – PASSENGER SURFACE ACCESS 41 3.2 National 8 C.1 Passenger Numbers 41 3.3 Local 8 C.2 Passenger Journeys by time of day 41 C.3 CAA Passenger Survey 43 4 London Luton Airport Today 10 C.4 Passenger Mode Shares 44 4.2 Bus and Coach 10 C.5 Passenger Mode Shares – by journey purpose and UK/non-UK origin 44 4.3 Rail 12 C.6 Passenger Catchment 46 4.4 On-site Bus Services 14 C.7 Passenger Mode Shares – by catchment 48 4.5 Road Access 14 C.8 Car and Taxi Use – by catchment 52 4.6 Car Parking 17 4.7 Taxis 18 APPENDIX D – STAFF SURFACE ACCESS 54 4.8 Walking and Cycling 18 D.1 Introduction 54 4.9 Accessibility 18 D.2 Staff Journeys – by time of day 54 4.10 Central Terminal Area 18 D.3 Staff Mode Shares 55 4.11 Onward Travel Centre 18 D.4 Staff Catchment 57 4.12 Staff Travelcard Scheme 19 D.5 Staff Mode Shares – by catchment 58 4.13 Employee Car Share Scheme 19 APPENDIX E – DfT ASAS GUIDANCE (1999) 59 5 Travel Patterns Today 20 5.1 Passenger Numbers 20 5.2 Passenger Mode Shares 20 5.3 Comparative Performance 22 5.4 Passenger Catchment 23 5.5 Achieving Mode Shift 24 5.6 Staff Travel 24 6 Objectives and Action Plans 26 6.2 Passengers 26 6.3 Staff 30 7 Stakeholder Engagement, Consultation and Monitoring 32 7.1 Stakeholder Engagement and Consultation 32 7.2 Airport Transport Forum 32 7.3 Monitoring 32 7.4 Reporting on Progress 34 2 Airport Surface Access Strategy 2012-2017 Contents 3 London Luton Airport is the fi fth busiest “passenger airport in the UK, with excellent transport links connecting it to London, the South East, the East of“ England Introduction and the South Midlands 11.1.1 London Luton Airport is the fi fth 1.1.3 This ASAS sets out challenging 1.1.5 The Strategy is divided into the busiest passenger airport in the new targets, with a view to building on following sections: UK, with excellent transport links this success. -

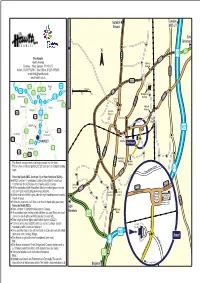

Hawth Map (PDF, 125.86

Gatwick London Airport M25 J7 East Grinstead N J10 A264 The Hawth A23 A2011 Hawth Avenue Crawley Crawley - West Sussex RH10 6YZ Avenue Admin: 01293 552941 - Box Office: 01293 553636 email: [email protected] B2036 www.hawth.co.uk A2011 Tesco A24 Biggin M25 J10 A23 A22 Hill 0 0.5miles M25 J9 A217 Caterham J5 0 0.5 1km A23 Hazelwick A3 Leatherhead J7 M25 Avenue D BY BUSINESS MAPS LTD FROM DIGITAL DATA - CROWN COPYRIGHT 43428U COPYRIGHT - CROWN DATA BUSINESS FROMD BY DIGITAL MAPS LTD Leisure A2220 J7 Sevenoaks A24 J8 J6 Park Dorking A21 A2004 Haslett Oxted PRODUCE Avenue Reigate Crawley A25 M23 Hospital A217 A22 Horley Three Bridges Gatwick J9 M23 A24 J10 East A264 Cranleigh Grinstead A281 CRAWLEY Crawley A264 J11 See Inset A23 Horsham A22 A29 A23 A24 A281 A2220 Southgate Avenue Hawth The Hawth is signposted on all major routes into the town. Avenue There is free on-site car parking for 250 cars and 13 disabled parking A2219 Road ges J10a bays. Brid Three A2004 From the South (M23 Junction 11) or from Horsham (A264): At M23 junction 11 roundabout coming from either the south or Horsham (on the A264) take the Crawley (A23) turning. Leisure A2220 ve At the roundabout (with Broadfield Stadium football ground on the Centre A2220 tt A A2220 K2 Hasle left) turn right onto Southgate Avenue (A2004). Broadfield Leisure slett Avenue Ha Paymaster At the third set of traffic lights, take the right hand lane and turn into Stadium Centre Sutherland General B2036 Hawth Avenue. Rbout House Follow the road and youll find us on the left hand side (see inset). -

M25 Offices & Occupational Markets Development Investment

Investment, Development & Occupational Markets M25 Offices Q1 2020 knightfrank.co.uk/research M25 OFFICES, Q1 2020 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY Covid 19 impedes occupier to 6.3% today. Between 2009 and 2010, and confidence in South East offices at activity in Q1 2.6m sq ft of space was delivered through the start of 2020. the pipeline which, coupled with some With political unrest seemingly behind tenant release space, fuelled a rise in UK Councils spending us and a solid Conservative majority vacancy to 10%. Today, completions continues in place, 2020 was meant to herald scheduled for 2020 and 2021 amount a period of relative calm meaning to 1.4m sq ft, of which just 1m sq ft is UK council spending continued in Q1, reassured firms would be able to enact speculative. This means that although with £47m committed across three both short and longer term occupational vacancy is expected to breach 7% in deals. Although this represented only strategies. However, the global spread 2021, because demand has slowed at 5% of turnover for the quarter, these of Covid-19 and containment measures the same time as supply, any market latest acquisitions meant that total imposed, has quickly reversed imbalance may not be as pronounced. spending between 2017 and 2020 by optimism, altered business focus and Inevitably, the supply side provides some local authorities rose to £2bn. The hindered transactional ability – albeit reassurance, but identifiable occupier subsector now represents 21% of in the closing stage of Q1. demand will be key for developers. investment volumes, meaning councils are the largest buyer group over this Subsequently, take-up in the first Financial terms largely period. -

Read the Masterplan

Live. Work. Visit. Final Report Subject to MVDC Executive Approval Live. Work. Visit. Contents 1 / Introduction 05 2 / Town Centre Context 09 3 / Consultation and Engagement 19 4 / Transform Leatherhead: Vision and Objectives 23 5 / Transform Leatherhead: Masterplan 29 6 / Accessibility 57 7 / Delivery and Implementation 65 1 / Introduction 1.1 Purpose of the Report • Form the basis of appointing a • Transform Leatherhead – Masterplan development partner(s). Baseline Report (Nexus Planning, This report has been prepared on August 2015); behalf of Mole Valley District Council In this context the purpose of this • Transform Leatherhead – Stage (MVDC) by Nexus Planning working report is to: 2 Consultation Report (Nexus with Broadway Malyan, Colliers Planning, January 2016); and International and Mouchel and details • Identify the strategic objectives in a strategy to transform Leatherhead transforming the town centre. These • Transform Leatherhead - Stage town centre. It provides a strategic have been developed through 3 Consultation Report (Nexus vision for the town centre, identifies extensive consultation with the local Planning, June 2016). a set of objectives and makes community and other stakeholders; recommendations on how the key • Ensure sites coming forward for MVDC is about to embark on the opportunity sites and projects can development fit together coherently preparation of a new Local Plan for be taken forward. The strategy is and contribute to the regeneration Mole Valley. This will establish the supported by recommendations on objectives for the area; type, amount and location of new delivery and an action plan which development that will be planned for in identifies where further work is • Provide guidance for developers, the District over the next ten to fifteen required. -

A71c8d55f858392b7596fbd4724

ermynhouse.co.uk ERMYN HOUSE PROVIDES STRIKING CAMPUS-STYLE OFFICES SET IN ERMYN WAY, LEATHERHEAD, SURREY, KT22 8UX MATURE LANDSCAPED Ermyn House was originally constructed in the GROUNDS 1990s as the headquarters of Esso (now Exxon) and comprises a single building over ground and two upper floors, with existing occupiers onsite including Exxon and Premium Credit. The property is located discreetly in beautiful wooded grounds just north of Leatherhead, but is only moments from Junction 9 of the M25, providing easy access to the wider motorway network, airports and central London. 2 Ermyn House, Ermyn Way, Leatherhead, Surrey, KT22 8UX Leatherhead, Surrey, Ermyn House, Way, 3 THE STRIKING CENTRAL ATRIUM AND SIZEABLE RECEPTION AREA PROVIDE REAL CORPORATE The property is arranged around a triple- PRESTIGE height glazed atrium with galleried landings, providing the centrepiece of the building and offering generous communal spaces for occupiers, including a café and informal seating areas. The main reception is large and reflects the corporate prestige Ermyn House can offer to incoming occupiers. Offices can be offered inclusive of furniture packages, subject to terms. 42 Exceptional parking at 1:240 sq ft Availability (IPMS3 approx) Ground Floor South 1 11,537 sq ft (1,071.82 sq m) Second Floor South 2 15,937 sq ft (1,480.60 sq m) Total 27,474 sq ft (2,552.42 sq m) Requirements can be accommodated from upwards of 5,000 sq ft. The property has an exceptional parking ratio of 1:241 sq ft approx, with additional licences spaces potentially available by separate agreement. Ermyn House has an EPC rating of D(76). -

Bus Routes September 2020 Route 1 Cheam, Epsom Downs, Epsom

Bus Routes September 2020 Route 1 Cheam, Epsom Downs, Epsom, Ashtead, Leatherhead, Fetcham, Bookham Location Stop Morning ETD Evening ETA Zone Cheam Northey Avenue 7.15am Route 5 4 Epsom Downs Tattenham Corner Pub 7.25am Route 5 4 Leatherhead Church Hall Car Park See below 5.15pm 2 Ashley Road Epsom 7.30am 5.00pm 3 Dentist/Atkins Bus Stop Ashtead Farm Lane Bus Stop 7.40am 4.50pm 2 Ashtead Village Club Ashtead 7.45am 4.45pm 2 Bus Stop/Parking bays West Farm Avenue Ashtead Post Box at junction with West 7.50am 4.40pm 2 Farm Close West Farm Avenue nr junction Ashtead 7.55am 4.35pm 2 with Barnett Wood Lane Leatherhead St John’s School 8.00am No Service 2 Leatherhead Church Hall Car Park 8.05am See above 2 Lower Road Fetcham 8.10am 4.20pm 1 Cobham Road end Bus Stop opposite Church Lower Bookham 8.15am 4.15pm 1 Road Manor House School 8.20am 4.10pm Route 2A - AM Wimbledon, Kingston, Surbiton, Thames Ditton, Esher, Cobham Location Stop Morning ETD Zone Wimbledon Ernle Road 7.00am 4 Coombe Lane Wimbledon nr junction with A3 7.10am 4 Spoons Café opp Holland Avenue Kingston Junction Studland Rd/St Albans Rd 7.25am 4 Kingston Canbury Gardens, Lower Ham Rd 7.30am 4 Portsmouth Road Surbiton Layby outside Fallows & Co (after 7.40am 4 Brighton Rd traffic lights) Giggs Hill Green Thames Ditton 7.45am 4 Bus Stop Esher Café Rouge 7.50am 4 Cobham ACS Bus Stop, Portsmouth Road 8.05am 2 Manor House School 8.25am Route 2B - AM Hinchley Wood, Claygate, Esher, Cobham Location Stop Morning ETD Zone Manor Road North Hinchley Wood 7.30am 4 Junction with Claygate