Excerpt • Temple University Press

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Punk : 40 Years & Not Dead Yet 40 Ans De No Future

MEDIATHEQUE DE SELESTAT 2, Espace Gilbert Estève 67604 SELESTAT Cedex Tél. 03.88.58.03.20 Fax 03.88.58.03.25 www.mediatheque-selestat.net Punk : 40 years & not dead yet 40 ans de No Future Discographie très sélective mais pas du tout objective ! SECTEUR MUSIQUE - Octobre 2017 Discographie consultable en ligne sur : www.mediatheque-selestat.net Définitions punk, adjectif invariable (anglais punk) Se dit d'un mouvement musical et culturel apparu en Grande-Bretagne vers 1975 et dont les adeptes affichent divers signes extérieurs de provocation (crâne rasé avec une seule bande de cheveux teints, chaînes, épingles de nourrice portées en pendentifs, etc.) afin de caricaturer la médiocrité de la société. (Larousse) punk, [poenk] nom et adjectif – 1973 ; mot angl. amér. « vaurien » ; pourri, délabré. Anglic. 1. N. m. Le punk : mouvement de contestation regroupant des jeunes qui affichent divers signes extérieurs de provocation (coiffure, vêtement) par dérision de l'ordre social. Adj. La musique punk. Les modes punk(s). 2. Un, une punk : adepte du punk. Les punks des années 80. On trouve parfois le fém. Punkette. (Le Petit Robert) Le punk, c'est avoir seize ans et dire non (Steve Severin, bassiste de Siouxsie & The Banshees) Le punk, c'est faire ce que l'on a envie de faire. C'est la liberté, la liberté totale, de ne pas être obligé de penser comme les autres, de vivre comme les autres. (Didier Wampas) Un peu d'histoire Le punk serait né à New-York dans les années 1974-1976 dans un petit club, le CBGB situé au 315 Bowery, à Manhattan. -

October 2019 New Releases

October 2019 New Releases what’s inside featured exclusives PAGE 3 RUSH Releases Vinyl Available Immediately! 82 Vinyl Audio 3 CD Audio 17 FEATURED RELEASES Music Video DVD & Blu-ray 52 SPYRO GYRA - WOODSTOCK: DINOSAUR JR. - VINYL TAP 3 DAYS THAT CHANGED WHERE YOU BEEN: Non-Music Video EVERYTHING 2CD DELUXE EXPANDED DVD & Blu-ray 57 EDITION Order Form 90 Deletions and Price Changes 93 800.888.0486 RINGU COLLECTION MY SAMURAI JIRGA 203 Windsor Rd., Pottstown, PA 19464 (COLLECTOR’S EDITION) FRED SCHNEIDER & THE SPYRO GYRA - WEDDING PRESENT - www.MVDb2b.com SUPERIONS - VINYL TAP TOMMY 30 BAT BABY MVD: RAISING HELL THIS FALL! We celebrate October with a gallery of great horror films, lifting the lid off HELLRAISER and HELLBOUND: HELLRAISER II with newly restored Blurays. The original and equally terrifying sequel are restored to their crimson glory by Arrow Video! HELLRAISER and its successor overflow with new film transfers and myriad extras that will excite any Pinhead! The Ugly American comes alive in the horror dark comedy AN AMERICAN WEREWOLF IN LONDON. Another fine reboot from Arrow Video, this deluxe pack will have you howling! Arrow also hits the RINGU with a release of this iconic Japanese-Horror film that spawned The Ring film franchise. Creepy and disturbing, RINGU concerns a cursed videotape, that once watched, will kill you in seven days! Watching this Bluray will have no such effect, but please, don’t answer the phone! TWO EVIL EYES from Blue Underground is a “double dose of terror” from two renowned directors, George A. Romero and Dario Argento. -

The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture

View metadata, citation and similarbrought COREpapers to youat core.ac.ukby provided by Leeds Beckett Repository The Strange and Spooky Battle over Bats and Black Dresses: The Commodification of Whitby Goth Weekend and the Loss of a Subculture Professor Karl Spracklen (Leeds Metropolitan University, UK) and Beverley Spracklen (Independent Scholar) Lead Author Contact Details: Professor Karl Spracklen Carnegie Faculty Leeds Metropolitan University Cavendish Hall Headingley Campus Leeds LS6 3QU 44 (0)113 812 3608 [email protected] Abstract From counter culture to subculture to the ubiquity of every black-clad wannabe vampire hanging around the centre of Western cities, Goth has transcended a musical style to become a part of everyday leisure and popular culture. The music’s cultural terrain has been extensively mapped in the first decade of this century. In this paper we examine the phenomenon of the Whitby Goth Weekend, a modern Goth music festival, which has contributed to (and has been altered by) the heritage tourism marketing of Whitby as the holiday resort of Dracula (the place where Bram Stoker imagined the Vampire Count arriving one dark and stormy night). We examine marketing literature and websites that sell Whitby as a spooky town, and suggest that this strategy has driven the success of the Goth festival. We explore the development of the festival and the politics of its ownership, and its increasing visibility as a mainstream tourist destination for those who want to dress up for the weekend. By interviewing Goths from the north of England, we suggest that the mainstreaming of the festival has led to it becoming less attractive to those more established, older Goths who see the subculture’s authenticity as being rooted in the post-punk era, and who believe Goth subculture should be something one lives full-time. -

The Ways of Whiskeyby Janelle

A Wicked woman • ty joseph, artist • Ames on missionaries and music ® JANUARY 4-10, 2019 / VOL. 41 / NO. 7 / LAWEEKLY.COM W ity he ar th ul er op fr p om of S ge co sur tlan up d, an Japa ying n or t s enjo he USA, the brown spirit i BY JANELLE THE WAYS OF WHISKEYBENNET L January 4-10, 2019 // Vol. 41 // No. 7 // laweekly.com ContentsDouble Barrel Room, Beverly Hills COURTESY DOUBLE B ARREL ROOM, BEVERLY7 HILLS GO LA...4 FILM...13 Arthur Omura tickles the ivories, NATHANIEL BELL rounds up the best new Fred Armisen performs “stand-up for releases and art-house classics on local musicians,” the Year of the Boar starts and screens this week. more to do and see in L.A. this week. MUSIC...14 FEATURE...7 Singer-songwriter Ames was inspired by Whether from Scotland, Japan or the both Hanson and her time with Christian U.S., whiskey is enjoying an upsurge of missionaries in Honduras. BY BRETT popularity. BY JANELLE BENNET. CALLWOOD. Plus: listings for ROCK & POP, JAZZ, CLASSICAL and more. CULTURE...11 We talked to Jackie Burns, who’s starring as Elphaba in Wicked at the Pantages. BY LINA LECARO. ADVERTISING ARTS...12 CLASSIFIED...19 Ty Joseph willed himself into being an EDUCATION/EMPLOYMENT...19 artist, and landed a solo show. BY DUSTIN CLENDENEN. REAL ESTATE/RENTALS...19 BULLETIN BOARD...19 On the Cover: Photography by M. Unal Ozmen/Shutterstock L.A. WEEKLY (ISSN #0192-1940 & USPS 461-370) is published weekly by LA Weekly LP, 724 S. -

The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk

UNIVERSITY OF CALIFORNIA Los Angeles Not All Killed by John Wayne: The Long History of Indigenous Rock, Metal, and Punk 1940s to the Present A thesis submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree Master of Arts in American Indian Studies by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 © Copyright by Kristen Le Amber Martinez 2019 ABSTRACT OF THESIS Not All Killed by John Wayne: Indigenous Rock ‘n’ Roll, Metal, and Punk History 1940s to the Present by Kristen Le Amber Martinez Master of Arts in American Indian Studies University of California Los Angeles, 2019 Professor Maylei Blackwell, Chair In looking at the contribution of Indigenous punk and hard rock bands, there has been a long history of punk that started in Northern Arizona, as well as a current diverse scene in the Southwest ranging from punk, ska, metal, doom, sludge, blues, and black metal. Diné, Apache, Hopi, Pueblo, Gila, Yaqui, and O’odham bands are currently creating vast punk and metal music scenes. In this thesis, I argue that Native punk is not just a cultural movement, but a form of survivance. Bands utilize punk and their stories as a conduit to counteract issues of victimhood as well as challenge imposed mechanisms of settler colonialism, racism, misogyny, homophobia, notions of being fixed in the past, as well as bringing awareness to genocide and missing and murdered Indigenous women. Through D.I.Y. and space making, bands are writing music which ii resonates with them, and are utilizing their own venues, promotions, zines, unique fashion, and lyrics to tell their stories. -

The Music (And More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report

The Music (and More) 2019 Quarter 3 Report Report covers the time period of July 1st to Kieran Robbins & Chief - "Sway" [glam rock] September 30th, 2019. I inadvertently missed Troy a few before that time period, which were brought to my attention by fans, bands & Moriah Formica - "I Don't Care What You others. The missing are listed at the end, along with an Think" (single) [hard rock] Albany End Note… Nine Votes Short - "NVS: 09/03/2019" [punk rock] RECORDINGS: Albany Hard Rock / Metal / Punk Psychomanteum - "Mortal Extremis" (single track) Attica - "Resurected" (EP) [hardcore metal] Albany [thrash prog metal industrial] Albany Between Now and Forever - "Happy" (single - Silversyde - "In The Dark" [christian gospel hard rock] Mudvayne cover) [melodic metal rock] Albany Troy/Toledo OH Black Electric - "Black Electric" [heavy stoner blues rock] Scotchka - "Back on the Liquor" | "Save" (single tracks) Voorheesville [emo pop punk] Albany Blood Blood Blood - "Stranglers” (single) [darkwave Somewhere To Call Home - "Somewhere To Call Home" horror synthpunk] Troy [nu-metalcore] Albany Broken Field Runner – "Lay My Head Down" [emo pop Untaymed - "Lady" (single track) [british hard rock] punk] Albany / LA Colonie Brookline - "Live From the Bunker - Acoustic" (EP) We’re History - "We’re History" | "Pop Tarts" - [acoustic pop-punk alt rock] Greenwich "Avalanche" (singles) [punk rock pop] Saratoga Springs Candy Ambulance - "Traumantic" [alternative grunge Wet Specimens - "Haunted Flesh" (EP) [hardcore punk] rock] Saratoga Springs Albany Craig Relyea - "Between the Rain" (single track) Rock / Pop [modern post-rock] Schenectady Achille - "Superman (A Song for Mora)" (single) [alternative pop rock] Albany Dead-Lift - "Take It or Leave It" (single) [metal hard rock fusion] Schenectady Caramel Snow - "Wheels Are Meant To Roll Away" (single track) [shoegaze dreampop] Delmar Deep Slut - "u up?" (3-song) [punk slutcore rap] Albany Cassandra Kubinski - "DREAMS (feat. -

New Music As Subculture Que Devient L’Avant-Garde ? La Nouvelle Musique Comme Sous-Culture Martin Iddon

Document generated on 09/29/2021 10:50 a.m. Circuit Musiques contemporaines What Becomes of the Avant-Guarded? New Music as Subculture Que devient l’avant-garde ? La nouvelle musique comme sous-culture Martin Iddon Pactes faustiens : l’hybridation des genres musicaux après Romitelli Article abstract Volume 24, Number 3, 2014 In a short ‘vox pop,’ written for Circuit in 2010, on the subject of the ‘future’ of new music, I proposed that new music — or the version of it tightly URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1027610ar intertwined with what was once thought of as the international avant-garde, at DOI: https://doi.org/10.7202/1027610ar any rate — might today be better thought of as a sort of subculture, akin to the spectacular subcultures of goth and punk, but radically different in that they See table of contents developed from the ‘grassroots,’ as it were, while new music comes from a position of extreme cultural privilege, which is to say it has access, even now, to modes of funding and infrastructure subcultures ‘proper’ never have. This essay develops this line of enquiry, outlining theories of subculture and Publisher(s) post-subculture — drawing on ‘classic’ and more recent research, from Les Presses de l’Université de Montréal Hebdige and Cohen to Hodkinson, Maffesoli, and Thornton — before presenting the, here more detailed, case that new music represents a sort of subculture, before making some tentative proposals regarding what sort of ISSN subculture it is and what this might mean for contemporary understandings of 1183-1693 (print) new music and what it is for. -

Psychobilly Psychosis and the Garage Disease in Athens

IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 5 – Issue 1 – Spring 2020 Psychobilly Psychosis and the Garage Disease in Athens Michael Tsangaris, University of Piraeus, Greece Konstantina Agrafioti, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Greece Abstract The complexity and the bizarre nature of Psychobilly as a music genre and as a music collectivity make it very convenient for reconsidering several views in relation to subcultures, neo-tribes and scenes. More specifically, the case of Greek Psychobilly can categorically present how subcultural trends can be disseminated across gender, social classes and national borders. This study aims to trace historically the scene of Psychobilly in Athens based on typical ethnographic research and analytic autoethnography. The research question is: Which are the necessary elements that can determine the existence of a local music scene? Supported by semi-structured interviews, the study examines how individuals related to the Psychobilly subculture comprehend what constitutes the Greek Psychobilly scene. Although it can be questionable whether there ever was a Psychobilly scene in Athens, there were always small circles in existence into which people drifted and stayed for quite a while, constituting the pure core of the Greek Psychobilly subculture. Keywords: psychobilly, music genres, Athens, Post-subcultural Theory 31 IAFOR Journal of Cultural Studies Volume 5 – Issue 1 – Spring 2020 Introduction According to the American Countercultures Encyclopaedia, Psychobilly is a subculture that emerged in the 1980s from the unlikely combination of rockabilly and punk rock. The provocative and sometimes outrageous style associated with psychobillies (also known as “psychos”) mixes the blue-collar rawness and rebellion of 1950s rockabilly with the confrontational do-it-yourself style of 1970s punk rock, a syncretism infused with themes from monster and horror films, campy sci-fi movies, and even professional wrestling” (Wojcik, 2013, p. -

23. Wave-Gotik-Treffen

23. Wave-Gotik-Treffen - Termin: 6. - 9. Juni 2014 - Ort: Leipzig (an rund 40 Veranstaltungsorten über die ganz Stadt verteilt), Zeltplatz und Hauptveranstaltungsort am Stadtrand auf dem agra-Messegelände Markkleeberg - Internetseiten: www.wave-gotik-treffen.de www.facebook.com/WaveGotikTreffen - Musikrichtungen: alle Arten von dunkler Musik: Gothic; EBM; Industrial; Dark Ambient; Apocalyptic Folk; Post Punk, Synthpop etc. - Eintrittskarten: 4-Tageskarte für alle Veranstaltungen im Rahmen des 23. Wave-Gotik-Treffens Pfingsten 2014 zu 99,- € im Vorverkauf (inkl. VVK-Gebühr). Die Veranstaltungskarte beinhaltet die Fahrtberechtigung für Nahverkehrsmittel (Straßenbahn, Busse, S-Bahn des MDV Zone 110) vom 6.Juni, 08:00 Uhr - 10.Juni, 12:00 Uhr (ohne Sonderlinien). - Zelten: mit Obsorgekarte zu 25,- € (inkl. VVK-Gebühr) mit folgendem Leistungspaket: Zeltplatznutzung auf dem Treffenzeltplatz „Pfingstbote“ – das ausführliche Treffen-Programmbuch Ohne Obsorge-Karte sind das Betreten und die Nutzung des Treffenzeltplatzes nicht möglich. Die Obsorge-Karte gilt nur in Verbindung mit einer Treffen-Veranstaltungskarte. - Parken: Für das Parken auf dem Treffengelände ist eine Parkvignette zu 15,- € (inkl. VVK-Gebühr) für den gesamten Treffen- Zeitraum erforderlich. Ohne Parkvignette ist das Parken auf dem Treffengelände (agra-Treffenpark) nicht möglich. Karten sind bestellbar über www.wave-gotik-treffen.de - Erwartete Besucherzahl: ca. 20000 - Kontakt: Fernruf: 0341-2120862 / E-Post: [email protected] - Photos: www.wave-gotik-treffen.de/photogallery.php Das Wave-Gotik-Treffen - schwarz-romantische Festspiele jedes Jahr zu Pfingsten in Leipzig 2014 findet das WGT zum 23.Mal statt. Vom 6. bis 9. Juni feiern wieder mehr als 20000 Gothics aus aller Welt DIE internationale Familienzusammenkunft der Gothic-Szene. Über die ganze Stadt verteilt werden etwa 200 Bands und Künstler auftreten und dabei erneut alle Spielarten dunkler Musik aufführen: Von Future-Pop bis Goth-Metal, von EBM bis Apocalyptic Folk, von mittelalterlichen Klängen bis zu elegischem Post Punk. -

The Evolution of Emo and Its Theoretical Implications 175

The Evolution of Emo and Its Theoretical Implications 175 Mirosław Aleksander Miernik The Evolution of Emo and Its Theoretical Implications The purpose of this article is to analyze how emo, a youth subculture, evolved in the United States during a period of approximately twenty five years, since the mid-1980s, particularly focusing on how it changed in regard to the zeitgeist of the time period, as well as how it appropriated various elements of past subcultures into itself in order to create its own subcultural identity. Special attention will be paid to the third incarnation, which emerged at the beginning of the twenty-first century and proved to be the most widespread variation of the subculture. It is also interesting how this incarnation was affected by historical events such as the Columbine High School Massacre and 9/11. The theoretical implications of emo are the second issue that this article at- tempts to tackle. In particular, when viewed from the perspective of post-subculture studies, it allows one to revisit certain theories of the Centre for Contemporary Cultural Studies at the University of Birmingham (CCCS), which pioneered sub- culture studies in the 1960s and 70s. The relationship between post-subculture studies and the CCCS’s approach has always been very complex. Even though many representatives of post-subculture studies criticized the CCCS for various shortcomings, most significantly for an a priori approach that ignores empirical evidence and limits the concept of authenticity within subcultures (Muggleton 19–30). At the same time, the work of the CCCS has been always treated with respect and considered a milestone. -

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "GH"

Everett Rock Band/Musician List "G-H" Last Update: 6/28/2020 "G-H" List for Bands/Musicians Genre* From & Genre a Gamble in the Litter F I Mukilteo Minimalist / Folk / Indie G2 RB S H IL R&B/Soul / rap / hip hop Gabe Mintz I R A Seattle Indie / Rock / Acoustic Gabe Rozzell/Decency F C Gabe Rozzell and The Decency Portland Folk / Country Gabriel Kahane P Brooklyn, NY Pop Gabriel Mintz I Seattle Indie Gabriel Teodros H Rp S S Seattle/Brooklyn NY Hip Hop / Rap / Soul Gabriel The marine I Long Island Indie Gabriel WolfChild SS F A Olympia Singer Songwriter / folk / Acoustic Gaby Moreno Al S A North Hollywood, CA Alternative / Soul / Acoustic Gackstatter R Fk Seattle Rock / Funk Gadjo Gypsies J Sw A Bellingham Jazz / Swing / Acoustic GadZooks P Pk Seattle Pop Pk Gaelic Storm W Ce A R Nashville, TN World / Celtic / Acoustic Rock Gail Pettis J Sw Seattle Jazz / Swing Galapagos Band Pr R Ex Bellingham progressive/experimental rock Galaxy R Seattle Rock Gallery of Souls CR Lake Stevens Rock / Powerpop / Classic Rock Gallowglass Ce F A Bellingham traditional folk and Irish tunes Gallowmaker DM Pk Bellingham Deathrock/Surf Punk Gallows Hymn Pr F M Bellingham Progressive Folk Metal Gallus Brothers C B Bellingham's Country / Blues / Death Metal Galperin R New York City bossa nova rock GAMBLERS MARK Sf Ry El Monte CA Psychobilly / Rockabilly / Surf Games Of Slaughter M Shelton Death Metal / Metal GammaJet Al R Seattle Alternative / Rock gannGGreen H RB Kent Hip Hop / R&B Garage Heroes B G R Poulsbo Blues / Garage / Rock Garage Voice I R Seattle's Indie -

Order Form Full

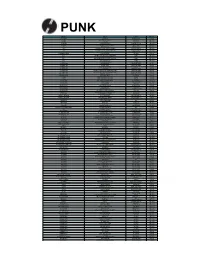

PUNK ARTIST TITLE LABEL RETAIL 100 DEMONS 100 DEMONS DEATHWISH INC RM90.00 4-SKINS A FISTFUL OF 4-SKINS RADIATION RM125.00 4-SKINS LOW LIFE RADIATION RM114.00 400 BLOWS SICKNESS & HEALTH ORIGINAL RECORD RM117.00 45 GRAVE SLEEP IN SAFETY (GREEN VINYL) REAL GONE RM142.00 999 DEATH IN SOHO PH RECORDS RM125.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (200 GR) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 THE BIGGEST PRIZE IN SPORT (GREEN) DRASTIC PLASTIC RM121.00 999 YOU US IT! COMBAT ROCK RM120.00 A WILHELM SCREAM PARTYCRASHER NO IDEA RM96.00 A.F.I. ANSWER THAT AND STAY FASHIONABLE NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. BLACK SAILS IN THE SUNSET NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. SHUT YOUR MOUTH AND OPEN YOUR EYES NITRO RM119.00 A.F.I. VERY PROUD OF YA NITRO RM119.00 ABEST ASYLUM (WHITE VINYL) THIS CHARMING MAN RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE ARCHIVE TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM108.00 ACCUSED, THE BAKED TAPES UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE NASTY CUTS (1991-1993) UNREST RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE OH MARTHA! UNREST RECORDS RM93.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (EARA UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACCUSED, THE RETURN OF MARTHA SPLATTERHEAD (SUBC UNREST RECORDS RM98.00 ACHTUNGS, THE WELCOME TO HELL GOING UNDEGROUND RM96.00 ACID BABY JESUS ACID BABY JESUS SLOVENLY RM94.00 ACIDEZ BEER DRINKERS SURVIVORS UNREST RM98.00 ACIDEZ DON'T ASK FOR PERMISSION UNREST RM98.00 ADICTS, THE AND IT WAS SO! (WHITE VINYL) NUCLEAR BLAST RM127.00 ADICTS, THE TWENTY SEVEN DAILY RECORDS RM120.00 ADOLESCENTS ADOLESCENTS FRONTIER RM97.00 ADOLESCENTS BRATS IN BATTALIONS NICKEL & DIME RM96.00 ADOLESCENTS LA VENDETTA FRONTIER RM95.00 ADOLESCENTS