Helping the Have-Nots: Examining the Relationship Between Rehabilitation Adherence and Self-Efficacy Beliefs in ACL Reconstructe

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Philly and the US Open Cup Final Posted by Ed Farnsworth on August 13, 2014 at 12:15 Pm

PHILADELPHIA SOCCER HISTORY / US OPEN CUP Philly and the US Open Cup Final Posted by Ed Farnsworth on August 13, 2014 at 12:15 pm Featured image: The Bethlehem Steel FC victory float after winning their second US Open Cup, then known as the National Challenge Cup, on May 6, 1916. (Photo: University Archives & Special Collections Department, Lovejoy Library, Southern Illinois University Edwardsville) Philadelphia teams, both amateur and professional, have a long history of appearances in the final of America’s oldest soccer competition, winning the US Open Cup ten times. The last Philadelphia team to do so was the Ukrainian Nationals in 1966. At PPL Park on Sept. 16 at 7:30 pm, the Philadelphia Union will look to restart that winning tradition. Before the US Open Cup Before the founding of the US Open Cup in the 1913–1914 season, the claim for a national soccer title was held by the American Cup competition, also known as the American Football Association Cup and the American Federation Cup. First organized by the American Football Association in 1885, the competition primarily featured teams from the early American soccer triangle of Northern New Jersey, Southern New York and lower New England. In 1897, the John A. Manz team became the first Philadelphia club to win the American Cup. Tacony won in 1910 with Philadelphia Hibernian losing in the final the following year. In 1914, Bethlehem Steel FC won the first of its six American Cup titles by beating Tacony, who had also lost to Northern New Jersey’s Paterson True Blues in the final the year before. -

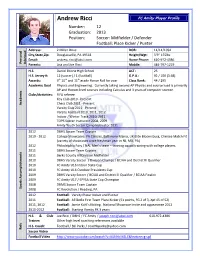

Andrew Ricci FC Amity Player Profile

Andrew Ricci FC Amity Player Profile Number: 12 Graduation: 2013 Position: Soccer: Midfielder / Defender Football: Place Kicker / Punter Address: 2 Miller Drive DOB: 11/11/1994 City,State,Zip: Douglassville, PA 19518 Height/Wgt: 5’9” 155lbs Email:on [email protected] Home Phone: 610-972-4386 Personal Personal Informati Parents: Lisa and Joe Ricci Mobile: 484-797-1219 H.S. Daniel Boone High School ACT: 25 H.S. Jersey #: 12 (soccer) / 1 (football) G.P.A.: 92 / 100 (3.68) Awards: 9th 10th and 11th grade Honor Roll for year Class Rank: 44 / 295 Academic Goal Physics and Engineering. Currently taking second AP Physics and course load is primarily AP and Honors level courses including Calculus and 3 years of computer science. Clubs/Activities: FIFA referee Key Club 2010 - Present Academic Chess Club 2011 - Present Varsity Club 2011 - Present Varsity Football 2010, 2011, 2012 Indoor / Winter Track 2010, 2011 TOPS Soccer Instructor 2008, 2009 Amity Youth Soccer Camp Instructor 2011 2012 DBHS Soccer Team Captain 2019 - 2012 College Showcases: PA Classics, Baltimore Mania, UK Elite Bloomsburg, Chelsea Match Fit (variety of showcases since freshman year in NJ, MD, PA) 2012 Philadelphia Fury / NAL Men’s team – training squad training with college players 2011 DBHS Soccer Team Captain 2011 Berks County All Division Midfielder 2010 DBHS Varsity Soccer / Division Champs / BCIAA and District III Qualifier 2010 FC Amity U16 Indoor State Cup 2010 FC Amity U16 Outdoor Presidents Cup 2009 DBHS Varsity Soccer / BCIAA and District III Qualifier / BCIAA Finalist Accomplishments 2009 FC Amity U17 / EPYSA State Cup Champion 2008 DBMS Soccer Team Captain Sports 2008 FC Revolution / Reading, PA 2012 Football: Varsity Placer Kicker and Punter 2011 Football: All Berks First Team Place Kicker (51 points, FG 2 of 3, Xpt 45 of 52) 2011, 2012 Football: Jamie Kohl’s Kicking. -

State Spared Storm's Fury

'Hi ■J-: THURSDAY, JUNE 22; 1OT8 MOOWIOH (A P ) D r. WU- iSanclii^Btier Ett^nftis diaUM from Mlddlahary, wen The Weathelp Gw tiag,BM tip pilw taiay in Cloudy, cori through Satur fha OwMi^BHeut Mato Uttory*s day with chance of scattered Ural foaitetty "Mighty rw*- Tiaakfc" showers; tonight’s low near 68— President Plays Global Diplomacy 868 BROAD ST. FRESHER 6Y FAR... tomorrow’s high about 66. MANCHESTER Pinehurst certified FRESH OtllCKBNS, BxeasU and Laga, ap- Maneheeter "A City o f VOtoge Charm (ear ofLm on Manchester tablea and at barbecuea. WAamcRON (AP) — P t m - trie* by latecA count, has been pUalied by more-timdttlonal low- Oonnallsr’ a montti*U»r global temember, pleaae, you gst more alioea of tender ohlokon from Mei* MIxan ia putting on an un- traveling aince June 6. er4evel dlptomacy, tour waa announced aa devoted toe ovisr 8 lb. blrda we feature and they are aa freah aa dally VOL. XO, N a 826 (TWBIjmr-TWO PAGES) MANCHESTER, CONN., FRIDAY, JUNE 28, 1972 Pi«« U) PRICE FIFTEEN CENTS uaual dbgilay o< h^li-level per- On July 2, mxon's aoienice Hie facta ot the current Jot- prim arily to current econom ic delivery can make them... aonal dlptomacy by Jetting top adviaer, Dr. Edward E. DavM tripptiHr abroaMl by WhaMi^ton laauea. However, the former > .1 iL.-a: ■***®*'^***^’"*y places around jr., will lead a delegatioa to notahlea do not appear to UiA Troaaury chief alM will be in a ROASTING CHICKEN 900 ^ globe. MOSCOW to woric out solentillo Into any atngle diplomatic maa- poaltlon to dlaouaa with foreign FRYERS — Cut-Up Ib. -

Temple University Men's Soccer

2014: SOUTHERN METHODIST UNIVERSITY AT TEMPLE UNIVERSITY TEMPLE UNIVERSITY MEN’S SOCCER 2014 GAME NOTES Korey Blucas, Graduate Extern for Athletic Communications Email: [email protected] O: 215-204-7446 C: 724-799-4480 Twitter: @Temple_Msoc Website: www.OwlSports.com GAME INFORMATION MATCHUP Date: ....................................................................Oct. 11, 2014 Time: ..........................................................................1:00 p.m. Site: ..............................Ambler Sports Complex (Ambler, Pa.) Live Video: ............................http://www.owlsports.com/watch/ Twitter Updates: ............................................@Temple_Msoc Series vs. SMU:........................................................Tied 0-0-1 TEMPLE RV SMU Streak:..................................................................................T 1 Owls Mustangs Last SMU Win: ................................................................None 2-7-2, 1-1-1 AAC 6-3-1, 2-0-1 AAC Last Temple Win: ............................................................None Home: 2-3-1, 1-0-1 Home: 6-1-0, 2-0-0 SCHEDULE Road: 0-4-1, 0-1-0 Road: 0-2-1, 0-0-1 AUGUST HEAD COACH HEAD COACH 29 Friday DREXEL . L, 1-0 (OT) David MacWilliams (Philadelphia ‘78) Tim McClements (Wheaton ‘87) 30 Sunday SACRAMENTO STATE . W, 3-0 Overall Record: 111-134-29 Overall Record: 146-143-27 SEPTEMBER at School: Same at School: 64-43-15 5 Friday #16 Penn State . L, 1-0 9 Tuesday Duke. L, 3-1 LAST TIME OUT LAST TIME OUT W, 2-0 vs Memphis 13 Saturday (6)La Salle . T, 2-2 T, 1-1 vs UCF 10/8/2014 10/8/2014 17 Wednesday Fordham . L, 1-0 (OT) 21 Sunday (6)PENN. L, 3-0 LEADERS LEADERS 24 Wednesday #23 DELAWARE . L, 3-0 Goals: Chas Wilson (3) Goals: Idrissa Camara (4) 27 Saturday *CINCINNATI . W, 2-0 Assists: Miguel Polley (3) Assists: Jared Rice (5) OCTOBER Points: Chas Wilson (7) Points: Idrissa Camara (9) 4 Saturday *#22 @USF . -

Terrae.E Ohamber of Oommeroe Letting out of Tourism Role

¢ PARL[Ag~ii, !~OIt.DfNOS, V£CTOR[/I, S.C., ~IL VSV-lX~ , I Reran STEEL& SJIJ,¥16E tml) ;:;:~:.~:~:*F,~ • ~~; ...... --" "'"*" ,_~.,~., " " wenuv 'i-:' l TERRACE.KIT AT the weather COPPER ' " BRASS~ / ALL METALS . .& BATTERIES, l Sunny today with the • / , uo,.. so. " / temperature in the mid 20% ,. l , 0P|N ,nLlJp'm. " / h the afternoon will bring a LoonIiu 8u1,0eve Phone IM-rdJ311 , slight northern breeze voLuME 72 No. 116 20' THURSDAY, JUNE 15, 1978 •~:•~:~:~:•;~:~:~::.*:~:~:~::::~::•z.*:.:.:::~/:~*:~:.~.~***F~**~/~:~:.~:,:.:.:.:.:.:.:~:.:.:,,...,~:•>>::,:;.:~:•:::.:~.~.. ~'~z:~/~.,~g~: ~,~,/~/,f//~#~.... ~.5:' ." " I Courthouse Rupert Mother Beat, Burned, Tortured OomesOloser / Terrace is me step closer Husband is Oharged Nine Months Later to getting the long awaited $6 million courthouse and NOTE: Burrard) criticized the Prince Rupert visited the health unit after council met The following press' release was received over RCMP's handling of the woman twice while she wu Monday night in committee the CP wire services Wednesday morning, case. in hospital here but the of the whole to accept the Ms. Brown said the woman woman suffered from am- most recent offer from the following a front page story in a Vancouver was found naked and neaia and "couldn't B•C. Building Curporatiou. daily, reporting the incident. See today's /~i.i bleeding by neighbors and remember anything." • The BCBC, the Crown Editorial on Page Four of today's paper. that she had suffered. A Vancouver RC]I~P corporation in charge of massive burns on her ab- spokesman said ,police here provincial building VANCOUVER (CP) -- An judge without Jury. domou and multiple burns no were ask~ to interv/ew the originally etoted they would RCMP spokesman said Michael Fulmer, district the chest,and face, woman and did so on one not contribute to costs of Tuesday flint more thannine Crown council at Prince Ru- Winarski said the charge occasion, last Sept. -

2017 Temple Men's Soccer Schedule

OwlSports.com TABLE OF CONTENTS QUICK FACTS 2017 TEMPLE MEN'S SOCCER SCHEDULE GENERAL INFORMATION Day Date Opponent ............................................................................................. Time Location ...................................................Philadelphia, Pa. Fri. Aug. 25 at Saint Joseph's ...................................................................................7:30 p.m. Enrollment ................................................................. 41,000 Tue. Aug. 29 at Villanova ................................................................................................... 4 p.m. Founded ........................................................................1884 Thu. Aug. 31 at Delaware ................................................................................................... 3 p.m. President ............................................. Richard M. Englert Sun. Sept. 3 RIDER...............................................................................................................7 p.m. Director of Athletics ................................Dr. Patrick Kraft Sat. Sept. 9 at St. John's ..............................................................................................7:30 p.m. NCAA Faculty Rep. ..............................Jeremy S. Jordan Sat. Sept. 16 at Fairfield ......................................................................................................7 p.m. Affiliation ................................................... NCAA Division I Tue. Sept. 19 -

The Ukrainian Weekly 1978, No.17

www.ukrweekly.com ТНЕ І СВОБОДА JfeSVOBODA І І " И УКРАЇНСЬКИЙ ЩОАІННИК ^ДОГ UHBAI NIAN OAltV Щ Щ UkroiniaENGLISH" LANGUAGnE WEEKL YWeekl EDITION y iVOL.LXXXV No. 97 THE UKRAINIAN WEEKLY SUNDAY, APRIL 30,1978 25 --і tySX!^ Khrystos Voskres - Christ Is Risen G50Q)0 let Us Be Jubilant' І Уристцрс Vyacheslaw Davydenko, Paschal Letter of the Sobor ^ ffOCK^CC/ Svoboda Editor, Die Of Bishops of the Ukrainian Autocephalous Orthodox Church Dearly beloved in Christ! Eyery great feast is filled with pro- founckreflections on the fundamental issues btf our existence. Prior to the greatest Ipast of our Church, Christ's Resurrection, we were filled with re minders of abominable events - Christ in the hands of executioners. Those who formerly greeted Him with palm branches were scattered. An un just trial occured and then suffering Mx. Davy unto death on the cross. His closest denko was born Vyacheslaw Davydtnfco friends were grief-stricken, friends who in the Kharkiv witnessed the miracles which their Tea region of Ukraine on July 25, 1905. He joined the Svoboda editorial staff on July cher worked, who witnessed His 20, 1953, and served as editor until his agonizing death. A heavy stone retirement on September 30, 1973. covered not only the grave of the Tea cher, but also expectations connected Ілюстрація M. Левицького Surviving him is his wife, Alia, a with His awaited victory. And all of a Ukrainian poet and writer. Та all our readers who celebrate Easter according to the Julian calendar we sudden, incredibly the stone moves, the The requiem will be held Monday, Mjqrl, stone is rolled away: Christ js risen! extend our best wishes and traditional wishes. -

Six Hospitalized in Truck Accident Meeting Members Who Give of Their Tractively Designed and the Shills, Resources, Md Tabour

/ , { TERRACE-KITIMAT 1 dal/ h ra i VOLUME 72 NO. 112 20 e . FRIDAY, JUNE 9, 1978 Kitimat- Pr. Rupert get ferry Kitimat is to soon receive B.C. Ferry Corporation service through Minette Bay • Marina's Mr. B. Orleans and the seventy feet Canadian Three. The contract to carry passengers from Kifimat to Prince Rupert, and Rupert to Kit/mat, has been signed, ! say marina, officials. This ferry will run two days a week and, as soon as the service begins, will be based in Prince Rup~t. Mr. Orleans . was No, it isn't the headquarters of ~ne Bicycle 1"nlef, What is unavailable forcommeat as going on inside? See photo at bottom of page: he was in Rupert attempting to acquire mooring space there. : Tentatively the route stops • Terrace chapel will include Port Simpson, Kincolith, Rupert and Kitimat.. , for L,B, Saints Presently the Canadian Members of The Church of first saints toembark in such Three, which is a completely Jesus Christ of Latter-day a project because, The changed boat. from the old Saints have purchased land Church of Jesus "Christ of Nschako I that it once was, is on the 4400 block of Waish Latter-day Saints is a word based in Kitimat. here in Terrace, and mw wide church with nearly four Prtcea will be set by the have set into motion a full million members throughout B.C. Ferry Corporation, • scale building fund drive, in the world, and in 1977 there according to marina per- order to nbtaln money for the were', over 500, chapels seunel. -

1 2016 U.S. Women's Football Leagues Addendum

2016 U.S. Women’s Football Leagues Addendum New Mexico Adult Football League – Women’s Division (NMAFL-W) – 2015 Season The NMAFL-W launched in 2015 with five teams in New Mexico. The Alamogordo Aztecs failed to complete the season, while the Amarillo Lady Punishers joined the league late and absorbed four forfeit losses before even getting out of the gate. But the Lady Punishers were formidable once they got started, upsetting the previously undefeated Roswell Destroyers in the playoffs to make it to the first NMAFL-W title game. That opened the door for the Santa Fe Dukes to swoop in and capture the NMAFL-W championship at the conclusion of the league’s first season. Regional League Teams: 5 Games: 22 (10) Championship game result: Santa Fe Dukes 12, Amarillo Lady Punishers 6 2015 NMAFL-W Standings Teams W L PR Status Roswell Destroyers (ROSD) 8 1 CC Expansion Santa Fe Dukes (SFD) 6 4 LC Expansion Northwest Wolves (NWW) 4 5 CC Expansion Amarillo Lady Punishers (ALP) 4 6 C Expansion Alamogordo Aztecs (AAZ) 0 6 -- Expansion 2015 NMAFL-W Scoreboard 1/18 ROSD 55 AAZ 0 3/14 NWW 1 ALP 0 4/19 ALP 6 NWW 0 3/15 SFD 1 AAZ 0 1/31 SFD 1 AAZ 0 3/15 ROSD 1 NWW 0 4/25 SFD 1 ALP 0 4/26 ALP 1 AAZ 0 2/15 ROSD 1 ALP 0 3/21 NWW 16 SFD 14 5/2 ALP 22 SFD 8 2/22 ROSD 28 SFD 22 * 3/29 NWW 1 AAZ 0 5/3 ROSD 1 NWW 0 2/22 NWW 42 AAZ 0 3/29 ROSD 1 SFD 0 5/17 SFD 1 NWW 0 CC 3/7 SFD 20 NWW 2 4/12 ROSD 20 ALP 6 5/17 ALP 22 ROSD 14 CC 3/7 ROSD 1 ALP 0 6/6 SFD 12 ALP 6 C Women’s Xtreme Football League (WXFL) – 2015 Season The WXFL debuted in 2015 with only two known teams: the Oklahoma City Lady Force and the Ponca City Lady Bulldogs. -

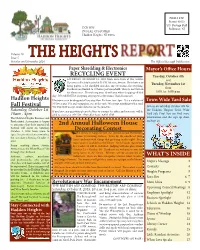

2016 October Heights Report

PRSRT STD Permit #1027 U.S. Postage Paid ECR WSS Bellmawr, NJ POSTAL CUSTOMER Haddon Heights, NJ 08035 Volume 29 Issue 5 THE HEIGHTS REPORT October and November 2016 The Official Borough Publication Paper Shredding & Electronics Mayor’s Office Hours RECYCLING EVENT Tuesday, October 4th SATURDAY, OCTOBER 15, 2016 from 8am-11am at The Service and Operations Facility located at 514 W. Atlantic Avenue. Residents may Tuesday, November 1st bring papers to be shredded and also any electronics for recycling. Residents are limited to 10 boxes per household. There is no limit on from the electronics. Please bring your id with you when dropping off that 4:00 to 6:00 p.m. day. We will NOT be accepting any paper or electronics from businesses. Haddon Heights Electronics can be dropped off any day Mon-Fri from 7am-3pm. It is a violation of Town Wide Yard Sale NJ law to put TVs and computers, etc. at the curb. We accept anything with a cord. Fall Festival We DO NOT accept smoke detectors or thermostats. Join us on Saturday October 8th for the Haddon Heights Town Wide Saturday, October 1st If you have any questions please feel free to contact the office and someone will be 10am - 4pm glad to assist you. 856-546-2580 office hours 8AM-4PM Yard Sale Day! You can find more The Haddon Heights Business and information and the sign up sheet Professional Association is happy on Page 24. to announce that their annual Fall 2nd Annual Halloween House Festival will occur on Saturday, October 1, 2016 from 10am to Decorating Contest The library is happy to host our second annual Halloween 4pm. -

Student Petitions Library Mortar Board Member Gathers Signatures to Protest Reduced Number of Hours by Darin Powell Fall Change," Be Said

ROTC simulates New restaurant, Mirage, s hostage crisis ............. becomes a reality ~. f page9 page 2 • II--IE EVIEWA FOUR-STAR ALL-AMERICAN NEWSPAPER Task force Police install aims to stop drug sexual crime hot line By Raetynn Tlbayan rape crisis center, and stated the Staff Reporter necessity or a paid coordina&or. The Anonymous tips posilion would include a minimum may help officials The Solutions to Sexual salary of$26,000. Violence Task Force (SSVTF) The third recommendation was track offenders issued a re.port Wednesday giving the development <lf new lhree reeommendalions 10 combat educational programs and By Chrtstlna Rinaldi the problems of sexual violence on awareness campaigns, such as an Stall Reporter campus, a wk force official said annual Rape Awareness Week. The Friday. week would include several A new drug-tip hot line will be Following a two-month effort 10 speakers, workshops and used by Delaware police 10 help develop solutions to sexual brochures, costing about $19,000. gain information about the seDing violence against women, SSVTF, a Included in the budget would be and abuse of illegal drugs, said sub-commiltee of the Commission about $2 I ,000 allocated for Capt. Charles Townsend of the on the Status of Women, called for materials to educate incoming Wilming&on Police. more university interaction with students and their parents. Wh is ties The hot line, 1-800-HAS-DRUG, the S.O.S. rope crisis cenlet and for would be given 10 all females and which opened Wednesday, is open students to stop "an increasing buttons saying "Men Against 24 hours a day, seven days a week problem," said Liane M. -

Airport Receives Grant from FAA Money Will Rehab Runway, Help Keep Wildlife Away from Planes

PAGE 4C FRIDAY, AUGUST 2, 2019 | The Sun | www.yoursun.com C Airport receives grant from FAA Money will rehab runway, help keep wildlife away from planes By LIZ HARDAWAY This project is anticipated to cost Miller said. STAFF WRITER This project is anticipated $6.2 million, with $2.9 million coming from to cost $6.2 million, with The average airbus, with $2.9 million coming from people, gas and luggage, FAA grants and $3.3 million coming from FAA grants and $3.3 million weighs 183,000 pounds. coming from passenger Allegiant’s planes departed passenger facility charges. facility charges. from and landed on one The airport anticipates of Punta Gorda Airport’s to start construction for (PGD) runways more 5,300 Kaley Miller said, especially of Transportation grants and both projects in November times last year, according to thanking project manager funds from accrued passenger and complete the project by their airline landing reports, Ron Ridenour. “He’s been facility charges. November 2020. totaling over 771 million working hard on it.” The grant funds will also The airport received four pounds. With these funds, the go toward the first phase of construction bids for the Now, in the first step of southern runway will be a wetland mitigation project, project in late May and many, the airport has secured extended 593 feet and its where 14 of 57 anticipated anticipates awarding the bid funding to rehabilitate one of existing pavement will be acres of existing wetlands to the second low bidder, the its runways. restored. The project also within the airport operations June project update states.