US Military Bases Negotiations

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Philippines After the May 10, 2010 Elections

126 KAS INTERNATIONAL REPORTS 9|2010 the PhiliPPineS after the May 10, 2010 electionS Peter Köppinger Dr. Peter Köppinger is Resident Represen- tative of the Konrad- On May 10, 2010, elections were held in the Philippi- Adenauer-Stiftung in nes. The president, vice president, the first chamber of the Philippines. parliament (House of Representatives), half of the 24 senators (second chamber of parliament), the governors of the 80 provinces, and the mayors and council members of the cities and municipalities of the country were elected into office. Presidential elections take place every six years in a political system that is broadly modeled on the political system of its former American colonial ruling power. The presidential elections represent a decisive point in Filipino politics for the following reasons. Different than in the United States, the extraordinarily powerful president cannot run for a second term and political parties do not play an important role in the country’s entirely person- alized election system. Situation before the electionS In 2001, Vice President Gloria Macapagal Arroyo (“GMA”) became president following a national uprising by the middle-class in the greater Manila area. With the strong support of the church, the uprising was led against corrupt President Joseph Estrada, a popular actor among the poor population. GMA, an economist hailing from one of the wealthiest families in the country, was highly respected. She was generally thought capable of building on the successful presidency of Fidel V. Ramos. During his six years in office between 1992 and 1998, Ramos was able to stabilize the democracy, which had only been reinstated in 1986 after the end of the Marcos dictatorship, and give the country an economic upswing through his bold reforms. -

Leveraging Presidential Power: Separation of Powers Without Checks and Balances in Argentina and the Philippines Susan Rose-Ackerman, Diane A

Leveraging Presidential Power: Separation of Powers without Checks and Balances in Argentina and the Philippines Susan Rose-Ackerman, Diane A. Desierto, and Natalia Volosin1 Abstract: Independently elected presidents invoke the separation of powers as a justification to act unilaterally without checks from the legislature, the courts, or other oversight bodies. Using the cases of Argentina and the Philippines, we demonstrate the negative consequences for democracy arising from presidential assertions of unilateral power. In both countries the constitutional texts have proved inadequate to check presidents determined to interpret or ignore the text in their own interests. We review five linked issues: the president’s position in the formal constitutional structure, the use of decrees and other law-like instruments, the management of the budget, appointments, and the role of oversight bodies, including the courts. We stress how emergency powers, arising from poor economic conditions in Argentina and from civil strife in the Philippines, have enhanced presidential power. Presidents seek to enhance their power by taking unilateral actions, especially in times of crisis, and then assert that the constitutional separation of powers is a shield that protects them from scrutiny and that undermines others’ claims to exercise checks and balances. Presidential power is difficult to control through formal institutional checks. Constitutional and statutory limits have some effect, but they also generate the search for ways to work around them. Both our cases illustrate the dangers of raising the separation of powers to a canonical principle without a robust system of checks and balances to counter assertions of executive power. Argentina and the Philippines may be extreme cases, but the fact that their recent constitutional revisions were explicitly designed to curb the president, should give us pause. -

Fr. Lorenzo Carraro, MCCJ

SIX SAINTLY POLITICIANSFr. Lorenzo Carraro, MCCJ Six Saintly Politicians By Fr. Lorenzo Carraro, MCCJ 2019 1 Table of contents Foreword 1. Giorgio La Pira (1904-1977): “My only party card is my baptism card” 2. Aldo Moro (1916-1978): Sacrificial Lamb 3. Benedicto Kiwanuka (1922-1972): Martyr of Justice 4. Raul Manglapus (1918-1999): A Renaissance Man 5. Alcide De Gasperi (1881-1954): An Outstanding Christian Politician 6. Igino Giordani (1894-1980): Mr. Fire $$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$$ 2 Foreword THE HIGHEST FORM OF CHARITY Pope Francis has recently repeated a statement which can surprise people: “Politics is one of the highest forms of charity” . To understand the truth of the statement we must overlook the common belief that people involved in politics are corrupt and remember that in Christ’s teaching authority is service: “You know that the rulers of the Gentiles lord it over them and their great men exercise authority over them. It shall not be so among you; but whoever would be great among you must be your servant, and whoever would be first among you must be your slave; even as the Son of Man came not to be served but to serve and to give his life as a ransom for many” (Matthew 20:25-28). The service that Jesus contemplates goes up to the sacrifice of one’s life, to bloody martyrdom, as it was with him. That is the case of the first president of independent Uganda, Benedicto Kiwanuka, who fell victim of the bloody dictator Idi Amin Dada. A sacrifice of blood was also the fate of Prof. -

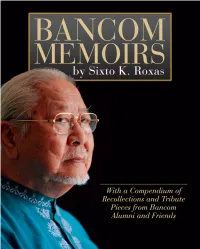

With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends

The ebook version of this book may be downloaded at www.xBancom.com This Bancom book project was made possible by the generous support of mr. manuel V. Pangilinan. The book launching was sponsored by smart infinity copyright © 2013 by sixto K. roxas Bancom memoirsby sixto K. roxas With a Compendium of Recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom Alumni and Friends Edited by eduardo a. Yotoko Published by PLDT-smart Foundation, inc and Bancom alumni, inc. (BaLi) contents Foreword by Evelyn R. Singson 5 Foreword by Francis G. Estrada 7 Preface 9 Prologue: Bancom and the Philippine financial markets 13 chapter 1 Bancom at its 10th year 24 chapter 2 BTco and cBTc, Bliss and Barcelon 28 chapter 3 ripe for investment banking 34 chapter 4 Founding eDF 41 chapter 5 organizing PDcP 44 chapter 6 childhood, ateneo and social action 48 chapter 7 my development as an economist 55 chapter 8 Practicing economics at central Bank and PnB 59 chapter 9 corporate finance at Filoil 63 chapter 10 economic planning under macapagal 71 chapter 11 shaping the development vision 76 chapter 12 entering the money market 84 chapter 13 creating the Treasury Bill market 88 chapter 14 advising on external debt management 90 chapter 15 Forming a virtual merchant bank 103 chapter 16 Functional merger with rcBc 108 chapter 17 asean merchant banking network 112 chapter 18 some key asian central bankers 117 chapter 19 asia’s star economic planners 122 chapter 20 my american express interlude 126 chapter 21 radical reorganization and BiHL 136 chapter 22 Dewey Dee and the end of Bancom 141 chapter 23 The total development company components 143 chapter 24 a changed life-world 156 chapter 25 The sustainable development movement 167 chapter 26 The Bancom university of experience 174 chapter 27 summing up the legacy 186 Photo Folio 198 compendium of recollections and Tribute Pieces from Bancom alumni and Friends 205 4 Bancom memoirs Bancom was absorbed by union Bank in 1981. -

MINDANAO (ARMM) ______5Th – 17Th May, 2007 (Election Was on 14Th May, 2007)

ANFREL OBSERVATION OF THE 2007 PHILIPPINE NATIONAL ELECTION IN THE AUTONOMOUS REGION OF MUSLIM MINDANAO (ARMM) _____________________________________________________ 5th – 17th May, 2007 (Election was on 14th May, 2007) Tribal leader Bong Cawed casted his vote on midterm elections in the hope that winning candidates will also give priority to the plight of the indigenous people nationwide 1 TABLE OF CONTENT TABLE OF CONTENT .......................................................................................................... 2 ABBRIVATION ...................................................................................................................... 3 ACKNOWLEDGEMENT ...................................................................................................... 4 Mindanao Map ........................................................................................................................ 5 INTRODUCTION ................................................................................................................... 6 LIPINOS WAY OF VOTING ................................................................................................ 7 ElectionS in Mindanao............................................................................................................ 9 ANFREL/TAF MISSION IN ARMM, 6 PROVINCES ...................................................... 9 SECURITY ............................................................................................................................ 11 1. PRE-ELECTION -

Death and the Maid: Work, Violence, and the Filipina in the International Labor Market

(c)1995 by the President and Fellows of Harvard College and the Harvard Women's Law Journal (now The Harvard Women's Law Journal): http://www.law.harvard.edu/students/orgs/jlg/ DEATH AND THE MAID: WORK, VIOLENCE, AND THE FILIPINA IN THE INTERNATIONAL LABOR MARKET DAN GATMAYTAN* If rape is inevitable, relax and enjoy it. —Raul Manglapus, Former Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Republic of the Philippines1 I. GENERAL INTRODUCTION AND ILLUSTRATION A. Introduction The above comment from the former Secretary of Foreign Affairs was made in the course of a Congressional hearing investigating reports that Iraqi soldiers occupying Kuwait were raping Filipina domestic helpers during the Persian Gulf Crisis in 1990. Women's groups attending the hearing called the remark a demonstration of "the low regard of the [Philippine] government for women."2 While improper and offensive, the Secretary's comment captured a common perception that Filipina over- seas domestic helpers are dispensable.3 While the Persian Gulf Crisis focused increased attention on their circumstances, the vulnerability of Filipina overseas contract workers ("OCWs") to violence existed long 230 Harvard Women's Law Journal [Vol. 20 before 1991. Nevertheless, the recent international publicity of violence against OCWs resulted in intense criticism of the Philippine govern- ment's policy of exporting labor. This Article analyzes the Philippine and international legal frame- works for the protection of Filipina overseas domestic helpers4 from violence5 and the effectiveness of these measures. Though the Philippine government's actions do not seem insignificant on paper, violence against these women persists. This Article posits that the Philippine and inter- national legal responses are ineffective. -

The Influence of Domestic and External Environment on Philippine

The Influence of Domestic and External Environment on Philippine Foreign Policy Changes: US Eviction in 1991, and the Enhanced Defense Cooperation Agreement Francis Martinez Esteban ABSTRACT The changes of foreign policy directives of the Philippines towards its alliance with the United States of America after Mt. Pinatubo eruption, and typhoon Haiyan are interesting cases to analyze. The United States was forced to move out of the Philippines after the Mt. Pinatubo eruption, while Washington signed a defense agreement with Manila to have a rotational presence in Philippine military bases after typhoon Haiyan. Using foreign policy analysis, specifically by tapping the influence of domestic and external factors on Manila’s foreign policy decision making, the research would explain why after similar natural disasters, the Philippines opted not to ratify another treaty for the maintenance of the US bases in 1991, while allowing the US to use Philippine military bases after typhoon Haiyan in 2014. Though given similar disaster circumstances, the disaster itself have only short-term significance in the decision making process. After Mt. Pinatubo eruption, the impact of the end of the Cold War (external environment) together with the growing Filipino nationalist sentiments (domestic environment) has influenced the Philippines to deny the US a continued presence of its military base. Meanwhile, the US pivot to Asia in 2011 (external environment), and Aquino’s military modernization and external balancing towards the rise of China (domestic environment) have dictated the Philippines decision to allow the US to have a presence once again, in Philippine military bases. Key words: US-Philippine Alliance, Domestic-External Influeces, Foreign policy changes Francis Martinez Esteban is a graduate of AB Political Science at the University of Santo Tomas –Manila. -

Stability and Performance of Political Parties in Southeast Asia Philippines, Party-Less No More? (Emerging Practices of Party Politics in the Philippines)

Stability and Performance of Political Parties in Southeast Asia Philippines, Party-Less No More? (Emerging Practices of Party Politics in the Philippines) Joy Aceron∗ Political Democracy and Reforms (PODER) Ateneo School of Government (ASoG) With support from Friedrich Naumann Stiftung for Liberty-Philippine Office Background The role of political parties in making democracy work is well-discoursed and, at least in theory, is also well-accepted. Worldwide, however, there is growing dissatisfaction towards parties and party politics. This is more apparent in countries where democracy is weak and parties serve other un-democratic purposes. Parties are supposed to serve the purpose of interest aggregation, leadership formation and candidate-selection. However, in some countries like the Philippines, parties have largely been a mechanism to facilitate patronage and personality-oriented politics. In the Philippines, much of the studies on political parties discuss how the lack of functioning political parties and under-developed or mal-developed party system weakens democratic practice. Studies on political parties have established the negative impact of wrongly-developed and underperforming political parties on democratization. Almonte would observe that “because of its weaknesses, the party system has failed to offer meaningful policy choices—and so to provide for orderly change” (2007; 66). In the same vein, Hutchcroft and Rocamora note that “Philippine-style democracy provides a convenient system by which power can be rotated at the top without effective participation of those below” (2003; 274). Other Philippine literature on political parties focus on eXplaining mal-development and under-performance of political parties (Timberman 1991; Lande 1965; Aceron, et.al. -

Inscriptions and Trajectories of Consumer Capitalism and Urban Modernity in Singapore and Manila

Monsoon Marketplace: Inscriptions and Trajectories of Consumer Capitalism and Urban Modernity in Singapore and Manila By Fernando Piccio Gonzaga IV A dissertation submitted in partial satisfaction of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric in the Graduate Division of the University of California, Berkeley Committee in charge: Professor Trinh T. Minh-ha, Chair Professor Samera Esmeir Professor Jeffrey Hadler Spring 2014 ©2014 Fernando Piccio Gonzaga IV All Rights Reserved Abstract Monsoon Marketplace: Inscriptions and Trajectories of Consumer Capitalism and Urban Modernity in Singapore and Manila by Fernando Piccio Gonzaga IV Doctor of Philosophy in Rhetoric University of California, Berkeley Professor Trinh T. Minh-ha, Chair This study aims to trace the genealogy of consumer capitalism, public life, and urban modernity in Singapore and Manila. It examines their convergence in public spaces of commerce and leisure, such as commercial streets, department stores, amusement parks, coffee shops, night markets, movie theaters, supermarkets, and shopping malls, which have captivated the residents of these cities at important historical moments during the 1930s, 1960s, and 2000s. Instead of treating capitalism and modernity as overarching and immutable, I inquire into how their configuration and experience are contingent on the historical period and geographical location. My starting point is the shopping mall, which, differing from its suburban isolation in North America and Western Europe, dominates the burgeoning urban centers of Southeast Asia. Contrary to critical and cultural theories of commerce and consumption, consumer spaces like the mall have served as bustling hubs of everyday life in the city, shaping the parameters and possibilities of identity, collectivity, and agency without inducing reverie or docility. -

Regime Change in the Philippines

change in the Philippines ation of the Aquino government Mark Turner, editor Political and Social Change Monograph 7 '*>teRfi&&> Political and Social Change Monograph 7 REGIME CHANGE IN THE PHILIPPINES THE LEGITIMATION OF THE AQUINO GOVERNMENT mark turner -' editor- ' ■ ■■ i" '■■< 'y Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University Canberra, 1987 P5 M. Turner and the several authors each in respect of the papers contributed by them; for the full list of the names of such copy-right owners and the papers in respect of which they are the copyright owners see the Table of Contents of this volume. This work is copyright. Apart from any fair dealings for the purpose of study, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission. Enquiries may be made to the publisher. First published 1987, Department of Political and Social Change, Research School of Pacific Studies, The Australian National University. Printed and manufactured in Australia by Highland Press. Distributed by Department of Political and Social Change Research School of Pacific Studies Australian National University GPO Box 4 CANBERRA ACT 2601 AUSTRALIA National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-publication entry Regime Change in the Philippines Bibliography Includes index. ISBN 0 7315 0140 3. 1. Philippines - Politics and government - 1973 I. Turner, Mark M. (Mark MacDonald), 1949 - II. Australian National University, Dept. of Political and Social Change. (Series: Political and social change monograph; 7). 959.9'046 Cover photograph by Wilfredo Salenga, courtesy of Asiaweek. 35" OWL CONTENTS Contributors iv Acknowledgements iv Abbreviations v 1. -

Democratic Deficits in the Philippines: What Is to Be Done?

Democratic Deficits in the Philippines: What is to be Done? CLARITA R. CARLOS AND DENNIS M. LALATA WITH DIANNE C. DESPI & PORTIA R. Carlos Democratic Deficits in the Philippines: What is to be Done? 2010 CLARITA R. CARLOS, Ph.D. and DENNIS M. LALATA with DIANNE C. DESPI and PORTIA R. CARLOS KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG Democratic Deficits in the Philippines: What is to be Done? Copyright 2010 by Clarita R. Carlos, Ph.D., Dennis M. Lalata, Dianne C. Despi and Portia R. Carlos ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Except for brief quotation in a review, this book or parts thereof, must not be reproduced in any form without permission in writing from the authors. The views and opinions expressed in this study are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect those of the Konrad Adenauer Foundation and of the Centrist Democratic Movement. Published by Center for Political and Democratic Reform, Inc. 13 Bautista Street., University of the Philippines Campus, Diliman, Quezon City Konrad Adenauer Foundation 5/F Cambridge Center Bldg. 108 Tordesillas corner Gallardo Streets Salcedo Village, Makati City Philippines Centrist Democratic Movement 804 Batis Street, Juna Subdivision Matina, Davao City Philippines ISBN 978-971-94932-0-4 Foreword When this book is published, many voices will be heard from civil society, the academe, the media and foreign observers in the Philippines expressing their hopes and great expectations for the strengthening of democratic good governance and a more successfull socio-economic development under the new administration of President Benigno Aquino III. His campaign, built on the credible promise of bringing down corruption and wrongdoings in the State Institutions, has opened perspectives for a better life for the ordinary people in the eyes of many Filipinos. -

Marcos V. Manglapus, GR No. L-88211, Oct 27, 1989, on the Right

Republic of the Philippines SUPREME COURT Manila EN BANC G.R. No. 88211 October 27, 1989 FERDINAND E. MARCOS, IMELDA R. MARCOS, FERDINAND R. MARCOS. JR., IRENE M. ARANETA, IMEE M. MANOTOC, TOMAS MANOTOC, GREGORIO ARANETA, PACIFICO E. MARCOS, NICANOR YÑIGUEZ and PHILIPPINE CONSTITUTION ASSOCIATION (PHILCONSA), represented by its President, CONRADO F. ESTRELLA, petitioners, vs. HONORABLE RAUL MANGLAPUS, CATALINO MACARAIG, SEDFREY ORDOÑEZ, MIRIAM DEFENSOR SANTIAGO, FIDEL RAMOS, RENATO DE VILLA, in their capacity as Secretary of Foreign Affairs, Executive Secretary, Secretary of Justice, Immigration Commissioner, Secretary of National Defense and Chief of Staff, respectively, respondents. R E S O L U T I O N EN BANC: In its decision dated September 15,1989, the Court, by a vote of eight (8) to seven (7), dismissed the petition, after finding that the President did not act arbitrarily or with grave abuse of discretion in determining that the return of former President Marcos and his family at the present time and under present circumstances pose a threat to national interest and welfare and in prohibiting their return to the Philippines. On September 28, 1989, former President Marcos died in Honolulu, Hawaii. In a statement, President Aquino said: In the interest of the safety of those who will take the death of Mr. Marcos in widely and passionately conflicting ways, and for the tranquility of the state and order of society, the remains of Ferdinand E. Marcos will not be allowed to be brought to our country until such time as the government, be it under this administration or the succeeding one, shall otherwise decide.