The Turkish Baths in Elbasan: Architecture, Geometry and Wellbeing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Door/Window Sensor DMWD1

Always Connected. Always Covered. Door/Window Sensor DMWD1 User Manual Preface As this is the full User Manual, a working knowledge of Z-Wave automation terminology and concepts will be assumed. If you are a basic user, please visit www.domeha.com for instructions. This manual will provide in-depth technical information about the Door/Window Sensor, especially in regards to its compli- ance to the Z-Wave standard (such as compatible Command Classes, Associa- tion Group capabilities, special features, and other information) that will help you maximize the utility of this product in your system. Door/Window Sensor Advanced User Manual Page 2 Preface Table of Contents Preface ................................................................................................................................. 2 Description & Features ..................................................................................................... 4 Specifications ..................................................................................................................... 5 Physical Characteristics ................................................................................................... 6 Inclusion & Exclusion ........................................................................................................ 7 Factory Reset & Misc. Functions ..................................................................................... 8 Physical Installation ......................................................................................................... -

Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation

W&M ScholarWorks Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects 2007 Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson College of William & Mary - Arts & Sciences Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.wm.edu/etd Part of the American Studies Commons, and the Music Commons Recommended Citation Johnson, Maya Ayana, "Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation" (2007). Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects. Paper 1539626527. https://dx.doi.org/doi:10.21220/s2-nf9f-6h02 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the Theses, Dissertations, & Master Projects at W&M ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Dissertations, Theses, and Masters Projects by an authorized administrator of W&M ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Harem Fantasies and Music Videos: Contemporary Orientalist Representation Maya Ayana Johnson Richmond, Virginia Master of Arts, Georgetown University, 2004 Bachelor of Arts, George Mason University, 2002 A Thesis presented to the Graduate Faculty of the College of William and Mary in Candidacy for the Degree of Master of Arts American Studies Program The College of William and Mary August 2007 APPROVAL PAGE This Thesis is submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Maya Ayana Johnson Approved by the Committee, February 2007 y - W ^ ' _■■■■■■ Committee Chair Associate ssor/Grey Gundaker, American Studies William and Mary Associate Professor/Arthur Krrtght, American Studies Cpllege of William and Mary Associate Professor K im b erly Phillips, American Studies College of William and Mary ABSTRACT In recent years, a number of young female pop singers have incorporated into their music video performances dance, costuming, and musical motifs that suggest references to dance, costume, and musical forms from the Orient. -

Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East

Viewpoints Special Edition Architecture and Urbanism in the Middle East The Middle East Institute Middle East Institute The mission of the Middle East Institute is to promote knowledge of the Middle East in Amer- ica and strengthen understanding of the United States by the people and governments of the region. For more than 60 years, MEI has dealt with the momentous events in the Middle East — from the birth of the state of Israel to the invasion of Iraq. Today, MEI is a foremost authority on contemporary Middle East issues. It pro- vides a vital forum for honest and open debate that attracts politicians, scholars, government officials, and policy experts from the US, Asia, Europe, and the Middle East. MEI enjoys wide access to political and business leaders in countries throughout the region. Along with information exchanges, facilities for research, objective analysis, and thoughtful commentary, MEI’s programs and publications help counter simplistic notions about the Middle East and America. We are at the forefront of private sector public diplomacy. Viewpoints is another MEI service to audiences interested in learning more about the complexities of issues affecting the Middle East and US relations with the region. To learn more about the Middle East Institute, visit our website at http://www.mideasti.org Cover photos, clockwise from the top left hand corner: Abu Dhabi, United Arab Emirates (Imre Solt; © GFDL); Tripoli, Libya (Patrick André Perron © GFDL); Burj al Arab Hotel in Dubai, United Arab Emirates; Al Faisaliyah Tower in Riyadh, Saudi Arabia; Doha, Qatar skyline (Abdulrahman photo); Selimiye Mosque, Edirne, Turkey (Murdjo photo); Registan, Samarkand, Uzbekistan (Steve Evans photo). -

Developing a Sustainability Plan for Hammams in Morocco

Worcester Polytechnic Institute Digital WPI Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) Interactive Qualifying Projects 2020-03-05 Developing a Sustainability Plan for Hammams in Morocco Alyssa Joy Sousa Worcester Polytechnic Institute Brian Preiss Worcester Polytechnic Institute Nathan S. Kaplan Worcester Polytechnic Institute Payton Bielawski Worcester Polytechnic Institute Rebekah Jolin Vernon Worcester Polytechnic Institute Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all Repository Citation Sousa, A. J., Preiss, B., Kaplan, N. S., Bielawski, P., & Vernon, R. J. (2020). Developing a Sustainability Plan for Hammams in Morocco. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.wpi.edu/iqp-all/5619 This Unrestricted is brought to you for free and open access by the Interactive Qualifying Projects at Digital WPI. It has been accepted for inclusion in Interactive Qualifying Projects (All Years) by an authorized administrator of Digital WPI. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Developing a Sustainability Plan for Hammams in Morocco An Interactive Qualifying Project submitted to the Faculty of WORCESTER POLYTECHNIC INSTITUTE in partial fulfilment of the requirements for the degree of Bachelor of Science by Payton S. Bielawski Nathan S. Kaplan Brian C. Preiss Alyssa J. Sousa Rebekah J. Vernon Date: 8 March 2020 Report Submitted to: Mr. Abdelhadi Bennis Association Ribat Al-Fath Professor Laura Roberts Professor Mohammed El Hamzaoui Worcester Polytechnic Institute This report represents work of WPI undergraduate -

Revitalization of the Bazaar Neighborhood in Tehran

REVITALIZATION OF THE BAZAAR NEIGHBORHOOD IN TEHRAN BY PARDIS MOINZADEH THESIS Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Landscape Architecture in Landscape Architecture in the Graduate College of the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign , 2014 Urbana, Illinois Adviser: P Professor D. Fairchild Ruggles Abstract The word “bazaar” comes from an ancient word “wazaar” meaning market. The word “baza” has been used in other countries such as Turkey, Arabic countries and India as well.1 Bazaars are historic market places that provide trade services as well as other functions. Their historic buildings are renowned for their architectural aesthetics, and in old cities such as Tehran (Iran) they are considered the centerpiece of activities with architectural, cultural, historical, religious, and commercial values. However, during the past 400 years, they have undergone social and environmental changes. The neighborhood of the Tehran Bazaar has in recent decades become degraded, which has consequently decreased the social value of the historic Bazaar. The ruined urban condition makes it impossible for contemporary visitors to have a pleasurable experience while visiting the Bazaar, although that was historically their experience. As Tehran began to grow, much of the trade and finance in the city has moved to the newly developed section of the city, diminishing the importance of the bazaars. Today, shoppers and residents living in the Bazaar neighborhood inhabit dilapidated buildings, while customers and tourists—when they go there at all—experience a neighborhood that lacks even the most basic urban amenities such as sidewalks, drainage, benches, trees and lighting. This design study required a number of investigations. -

Bazaars and Bazaar Buildings in Regency and Victorian London’, the Georgian Group Journal, Vol

Kathryn Morrison, ‘Bazaars and Bazaar Buildings in Regency and Victorian London’, The Georgian Group Journal, Vol. XV, 2006, pp. 281–308 TEXT © THE AUTHORS 2006 BAZAARS AND BAZAAR BUILDINGS IN REGENCY AND VICTORIAN LONDON KATHRYN A MORRISON INTRODUCTION upper- and middle-class shoppers, they developed ew retail or social historians have researched the the concept of browsing, revelled in display, and Flarge-scale commercial enterprises of the first discovered increasingly inventive and theatrical ways half of the nineteenth century with the same of combining shopping with entertainment. In enthusiasm and depth of analysis that is applied to the devising the ideal setting for this novel shopping department store, a retail format which blossomed in experience they pioneered a form of retail building the second half of the century. This is largely because which provided abundant space and light. Th is type copious documentation and extensive literary of building, admirably suited to a sales system references enable historians to use the department dependent on the exhibition of goods, would find its store – and especially the metropolitan department ultimate expression in department stores such as the store – to explore a broad range of social, economic famous Galeries Lafayette in Paris and Whiteley’s in and gender-specific issues. These include kleptomania, London. labour conditions, and the development of shopping as a leisure activity for upper- and middle-class women. Historical sources relating to early nineteenth- THE PRINCIPLES OF BAZAAR RETAILING century shopping may be relatively sparse and Shortly after the conclusion of the French wars, inaccessible, yet the study of retail innovation in that London acquired its first arcade (Royal Opera period, both in the appearance of shops and stores Arcade) and its first bazaar (Soho Bazaar), providing and in their economic practices, has great potential. -

Moorish Architectural Syntax and the Reference to Nature: a Case Study of Algiers

Eco-Architecture V 541 Moorish architectural syntax and the reference to nature: a case study of Algiers L. Chebaiki-Adli & N. Chabbi-Chemrouk Laboratoire architecture et environnement LAE, Ecole polytechnique d’architecture et d’urbanisme, Algeria Abstract The analogy to nature in architectural conception refers to anatomy and logical structures, and helps to ease and facilitate knowledge related to buildings. Indeed, several centuries ago, since Eugène Violet-le-Duc and its relationship to the botanic, to Phillip Steadman and its biological analogy, many studies have already facilitated the understanding and apprehension of many complex systems, about buildings in the world. Besides these morphological and structural aspects, environmental preoccupations are now imposing themselves as new norms and values and reintroducing the quest for traditional and vernacular know-how as an alternative to liveable and sustainable settlements. In Algiers, the exploration of traditional buildings, and Moorish architecture, which date from the 16th century, interested many researchers who tried to elucidate their social and spatial laws of coherence. An excellent equilibrium was in effect, set up, by a subtle union between local culture and environmental adaptability. It is in continuation of André Ravéreau’s architectonics’ studies that this paper will make an analytical study of a specific landscape, that of a ‘Fahs’, a traditional palatine residence situated at the extra-mural of the medieval historical town. This ‘Fahs’ constitutes an excellent example of equilibrated composition between architecture and nature. The objective of this study being the identification of the subtle conjugation between space syntax and many elements of nature, such as air, water and green spaces/gardens. -

Islamic Domes of Crossed-Arches: Origin, Geometry and Structural Behavior

Islamic domes of crossed-arches: Origin, geometry and structural behavior P. Fuentes and S. Huerta Polytechnic University of Madrid, Spain ABSTRACT: Crossed-arch domes are one of the earliest types of ribbed vaults. In them the ribs are intertwined forming polygons. The earliest known vaults of this type are found in the Great Mosque of Córdoba in Spain built in the mid 10th century, though the type appeared later in places as far as Armenia or Persia. This has generated a debate on their possible origin; a historical outline is given and the different hypotheses are discussed. Geometry is a fundamental part and the different patterns are examined. Though geometry has been thoroughly studied in Hispanic-Muslim decoration, the geometry of domes has very rarely been considered. The geometrical patterns in plan will be examined and afterwards, the geometric problems of passing from the plan to the three-dimensional space will be considered. Finally, a discussion about the possible structural behaviour of these domes is sketched. Crossed-arch domes are a singular type of ribbed vaults. Their characteristic feature is that the ribs that form the vault are intertwined, forming polygons or stars, leaving an empty space in the centre. The fact that the earliest known vaults of this type are found in the Great Mosque of Córdoba, built in the mid 10th century, has generated a debate on their possible origin. The thesis that appears to have most support is that of the eastern origin. This article describes the different hypothesis, to then proceed with a discussion of the geometry. -

Dome Construction

DOME CONSTRUCTION For further information on dome construction Application of Domes: Blue mosque, XVIth century – Istanbul, Turkey Please contact: ( Æ 23.50 m, 43 m high) n Plain masonry built with blocks or bricks n Floors for multi-storey buildings, they can be leveled flat n Roofs, they can be left like that and they will be waterproofed UNITED NATIONS CENTRE n Earthquakes zones, they can be used with a reinforced ringbeam FOR HUMAN SETTLEMENTS They are Built Free Spanning: (UNCHS - HABITAT) n It means that they are built without form n This way is also called the Nubian technique PO Box 30030, Nairobi, KENYA Timber Saving: Phone: (254-2) 621234 n Domes are built with bricks and blocks (rarely with stones) Fax: (254-2) 624265 Variety of Plans and Shapes: E-mail: [email protected] Treasure of Atreus – Tomb of Agamemnon (Æ +/- 18m) n Domes can be built on round, square, rectangular rooms, etc. Mycene, Greece (+/- 1500 BC) n They allow a wider variety of shapes than vaults AUROVILLE BUILDING CENTRE Stability Study: (AVBC / EARTH UNIT) n The shape of a dome is crucial for stability, and a stability study is Office, often needed. Be careful, a wrong shape will collapse Auroshilpam, Auroville - 605 101 Dhyanalingam Temple – Coimbatore, India Auroville, India elliptical section ( Æ 22.16 m, 9.85 m high) (3.63 m side, Need of Skilled Masons: Tamil Nadu, INDIA 0.60 m rise) n Building a dome requires trained masons. Never improvise when Phone: +91 (0)413-622277 / 622168 building domes, ask advice from skilled people Fax: +91 (0)413-622057 -

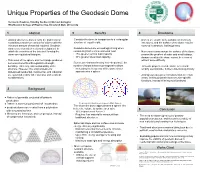

Unique Properties of the Geodesic Dome High

Printing: This poster is 48” wide by 36” Unique Properties of the Geodesic Dome high. It’s designed to be printed on a large-format printer. Verlaunte Hawkins, Timothy Szeltner || Michael Gallagher Washkewicz College of Engineering, Cleveland State University Customizing the Content: 1 Abstract 3 Benefits 4 Drawbacks The placeholders in this poster are • Among structures, domes carry the distinction of • Consider the dome in comparison to a rectangular • Domes are unable to be partitioned effectively containing a maximum amount of volume with the structure of equal height: into rooms, and the surface of the dome may be formatted for you. Type in the minimum amount of material required. Geodesic covered in windows, limiting privacy placeholders to add text, or click domes are a twentieth century development, in • Geodesic domes are exceedingly strong when which the members of the thin shell forming the considering both vertical and wind load • Numerous seams across the surface of the dome an icon to add a table, chart, dome are equilateral triangles. • 25% greater vertical load capacity present the problem of water and wind leakage; SmartArt graphic, picture or • 34% greater shear load capacity dampness within the dome cannot be removed • This union of the sphere and the triangle produces without some difficulty multimedia file. numerous benefits with regards to strength, • Domes are characterized by their “frequency”, the durability, efficiency, and sustainability of the number of struts between pentagonal sections • Acoustic properties of the dome reflect and To add or remove bullet points structure. However, the original desire for • Increasing the frequency of the dome closer amplify sound inside, further undermining privacy from text, click the Bullets button widespread residential, commercial, and industrial approximates a sphere use was hindered by other practical and aesthetic • Zoning laws may prevent construction in certain on the Home tab. -

The Change of the Hospital Architecture from the Early Part of 20Th Century to Nowadays: an Example of Konya

New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences Volume 4, Issue 11, (2017) 23-34 ISSN:2547-8818 www.prosoc.eu Selected Paper of 6th World Conference on Design and Arts (WCDA 2017), 29 June – 01 July 2017, University of Zagreb, Zagreb – Croatia The Change of the Hospital Architecture from the Early Part of 20th Century to Nowadays: An Example of Konya Dicle Aydin a*, Department of Architecture, Necmettin Erbakan University, 42090 Konya, Turkey. Esra Yaldiz b, Department of Architecture, Necmettin Erbakan University, 42090 Konya, Turkey. Suheyla Buyuksahin c, Department of Architecture, Selcuk University, 42075 Konya, Turkey. Suggested Citation: Aydin, D., Yaldiz, E. & Buyuksahin, S. (2017). The change of the hospital architecture from the early part of 20th century to nowadays: an example of Konya. New Trends and Issues Proceedings on Humanities and Social Sciences. [Online]. 4(11), 23-34. Available from: www.prosoc.eu Selection and peer review under responsibility of Prof. Dr. Ayse Cakir Ilhan, Ankara University, Turkey. ©2017 SciencePark Research, Organization & Counseling. All rights reserved. Abstract The hospitals that served in the name of ‘darussifa’ in Seljuk Empire period in Anatolia continued their service during Ottoman Empire period. The health institutions in different areas in Ottoman period were replaced by ‘Gureba hospitals’ in 19th century. The change in Anatolia was realised, after the declaration of the Republic and with the development of its economy, and lived in every area; hospital buildings were constructed first as ‘Gureba hospitals’ then as ‘country hospitals’ in Anatolia cities like Konya after the big cities like İstanbul, Ankara and İzmir. -

The Emotive Power of an Evolving Symbol: the Idea of the Dome from Kurgan Graves to the Florentine Tempio Israelitico

Ori Z. Soltes, Georgetown University The Emotive Power of an Evolving Symbol: The Idea of the Dome from Kurgan Graves to the Florentine Tempio Israelitico Preliminaries: Complementarity and Contradiction It is a truism within the history of art and architecture that a given visual form may symbolize more than one idea simultaneously - even ideas that contradict each other, although there is usually a logic to the apparent contradiction. Thus in abstract Islamic art, for example, the relationship between God and humanity might be symbolized by a monumental structure - such as a domed building or the mihrab form on a prayer rug - overrun with minutely detailed decoration. In that case, the decoration, in being minute, symbolizes humanity, while its monumental framework symbolizes God. But simultaneously, the framework, in being, as a frame, finitizing, symbolizes humanity, while the infinitizing pattern truncated by the frame symbolizes the God who is infinite. Thus ‘monumental’ versus ‘minute’ and ‘infinite’ versus ‘finite’ are visually presented in an interwoven array of apparent contradictions that nonetheless offer a logic to their interweave. For God is by definition utterly other than humanity, yet, according to the Muslim - and Jewish and Christian - tradition, God breathes the soul into us that makes us more than a clod of earth (Bible) or a bloodclot (Qur’an), which means that, in some sense, we are like God. And therefore in some sense God must be like us. So the simultaneous similitude and absolute alterity of that relationship is effectively conveyed by the relationship among these abstract visual elements. We may see this art historical principle well articulated by the dome form.