Grigory Rasputin in the Mirror of Western Screen

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Analysis of Factors in the Russian Revolutionary

AN ANALYSIS OF FACTORS IN THE ---- RUSSIAN REVOLUTIONARY MOVEMENT By Rev . Paul OtBrien, S. C. J. A Theaia submitted to the Pacultyot the Graduate Sohool, Marquette University, in Partial Fulfillment ot the Re quirements tor the Degree of Master of Arts .. · Milwauke., Wisconsin ay, 1948 O(Jl:ltents n.:.1"\9 ~ l1:'efQoe ••••• ~4o ............... jO .. .. .. ', ......... .... " ....... .. 1 lhapter I 'A'he Hist,orioal Ba ok~round , . 'l'he Husstan Intel116eIl1a~:ta ............. ~ ....., ••• ,......... .. 6 The i. r:l t:tngs ot ilJ.exander He r zen ••, ' • .,., ... it ....... ., ..... a ,ahernyehevs1:cl nnd his ldeas, l?ete"r LavrOV ...... jO ..... 10 Bel:1:n.sky end Ba ~~unl n .... I. ;0 '••••••••• ;0 ....., .................11 Tt:;.aohev and Plekhanov f theori ate or revolution ... II •• la tater Russian Ll terature • •••••• '••••• ' ••••' .......... " .la rxinm (lna lta influence ... ....... ...................16 'he Poll tioal. Phaae 11 at'O'noal Qb j eO' tl 'ICS of '1'ea r i ,slG..., it •••' .......... 20 The l:leoembl'i,sts .............. .. ... .. .............. ,.... 23 'rhe re:tr!n of' Mi ollOlu.s II ........................... ... 26 Chapter II 'J.1he lnf,luenoe of .Pe).'~ona11 ties p - l The T·ger Nl chalas II ........ .... '. '... .. ..... II! II! .......... 34 The ..c;mp l,,~ s 9 end Has put111 • •, ••••• , .... .... '" • "'. "' ••• "' .. 39 cn1n •• • '. "". •• Ie !•• •• • " ••• 0 • ~ ••••• • .•• Ct ................, . 44 '.i:rotsk y ........' .,Ii. II ••••••• :0 •••• ;0 .. '" '" w' .... '" '" '. '.... '" ••• ",. 47 Ohapter III The Influ ~ nl3e_ of the fiar The ~. ar and 1 ts effeots •••••• '" . .... ............... 5., 1sta1:;es i ntbe \'lo r e ttort and the! r effeot. "' •••• 5 he Vlar years of Ni aholas II . ........... '0., ••• "' ••• • 57 he lIar and i ts effcot on Huss1an eoonolay ......... 59 The f all of the uonorohy ••••••••••••••••••••••••• G2 Chapter IV Pase The Soviets Strussl. -

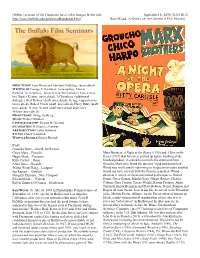

Online Versions of the Handouts Have Color Images & Hot Urls September

Online versions of the Handouts have color images & hot urls September 6, 2016 (XXXIII:2) http://csac.buffalo.edu/goldenrodhandouts.html Sam Wood, A NIGHT AT THE OPERA (1935, 96 min) DIRECTED BY Sam Wood and Edmund Goulding (uncredited) WRITING BY George S. Kaufman (screenplay), Morrie Ryskind (screenplay), James Kevin McGuinness (from a story by), Buster Keaton (uncredited), Al Boasberg (additional dialogue), Bert Kalmar (draft, uncredited), George Oppenheimer (uncredited), Robert Pirosh (draft, uncredited), Harry Ruby (draft uncredited), George Seaton (draft uncredited) and Carey Wilson (uncredited) PRODUCED BY Irving Thalberg MUSIC Herbert Stothart CINEMATOGRAPHY Merritt B. Gerstad FILM EDITING William LeVanway ART DIRECTION Cedric Gibbons STUNTS Chuck Hamilton WHISTLE DOUBLE Enrico Ricardi CAST Groucho Marx…Otis B. Driftwood Chico Marx…Fiorello Marx Brothers, A Night at the Opera (1935) and A Day at the Harpo Marx…Tomasso Races (1937) that his career picked up again. Looking at the Kitty Carlisle…Rosa finished product, it is hard to reconcile the statement from Allan Jones…Ricardo Groucho Marx who found the director "rigid and humorless". Walter Woolf King…Lassparri Wood was vociferously right-wing in his personal views and this Sig Ruman… Gottlieb would not have sat well with the famous comedian. Wood Margaret Dumont…Mrs. Claypool directed 11 actors in Oscar-nominated performances: Robert Edward Keane…Captain Donat, Greer Garson, Martha Scott, Ginger Rogers, Charles Robert Emmett O'Connor…Henderson Coburn, Gary Cooper, Teresa Wright, Katina Paxinou, Akim Tamiroff, Ingrid Bergman and Flora Robson. Donat, Paxinou and SAM WOOD (b. July 10, 1883 in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania—d. Rogers all won Oscars. Late in his life, he served as the President September 22, 1949, age 66, in Hollywood, Los Angeles, of the Motion Picture Alliance for the Preservation of American California), after a two-year apprenticeship under Cecil B. -

The Wicker Husband Education Pack

EDUCATION PACK 1 1 Contents Introduction Introduction ......................................................................................................................................................................... 3 Section 1: The Watermill’s Production of The Wicker Husband ........................................................................ 4 A Brief Synopsis.................................................................................................................................................................. 5 Character Profiles…………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………....…8 Note from the Writer…………………………………………..………………………..…….……………………………..…………….10 Interview with the Director ………………………….……………………………………………………………………..………….. 13 Section 2: Behind the Scenes of The Watermill’s The Wicker Husband …………………………………..… ...... 15 Meet the Cast ................................................................................................................................................................... 16 An Interview with The Musical Director .................................................................................................................. .20 The Design Process ......................................................................................................................................................... 21 The Wicker Husband Costume Design ...................................................................................................................... 23 Be a Costume Designer……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..25 -

Avalon Announce Edinburgh Festival Fringe Line-Up for 2014

AVALON ANNOUNCE EDINBURGH FESTIVAL FRINGE LINE-UP FOR 2014 Monday, 28th April 2014 Avalon announce the full line-up for their 26th year at the Edinburgh Festival Fringe, with the chance to see: FRANK SKINNER performing stand-up at the Fringe for the first time in seven years, limited runs from established and award- winning comics AL MURRAY, CHRIS RAMSEY and RUSSELL KANE, a follow-up hour from 2013 Edinburgh Comedy Award nominee CARL DONNELLY, a first solo UK appearance by US comic TOM SHILLUE and a host of other debut shows, musical, sketch, political comedy and theatrical productions for a fully-charged 26th anniversary at the Fringe. Tickets for all shows are available to buy from Tuesday 13th May on www.edinburghsbestcomedy.com. During the last 26 years, Avalon has promoted more Edinburgh Comedy Award winners and nominees than any other company including: CHRIS ADDISON, GREG DAVIES, DAVE GORMAN, HARRY HILL, RUSSELL HOWARD, RUSSELL KANE, THE MIGHTY BOOSH, CARL DONNELLY, AL MURRAY, KRISTEN SCHAAL & KURT BRAUNOHLER, ROISIN CONATY, GARTH MARENGHI and FRANK SKINNER and two of only four female winners of the prestigious Edinburgh Comedy Award; JENNY ECLAIR and LAURA SOLON. Avalon’s line-up for 2014 includes: AL MURRAY THE PUB LANDLORD - One Man One Guvnor - Work in Progress AL MURRAY THE PUB LANDLORD - The Pub Landlord’s Summer Saloon ALEX HORNE - Monsieur Butterfly ALEX HORNE - The Percentage Game CARL DONNELLY - Now That’s What I Carl Donnelly! Volume VI CARL HUTCHINSON - Here’s Me Show THE COMEDY ZONE CHRIS RAMSEY - The Most Dangerous -

Hooray for Hollywood!

Hooray for Hollywood! The Silent Screen & Early “Talkies” Created for free use in the public domain American Philatelic Society ©2011 • www.stamps.org Financial support for the development of these album pages provided by Mystic Stamp Company America’s Leading Stamp Dealer and proud of its support of the American Philatelic Society www.MysticStamp.com, 800-433-7811 PartHooray I: The Silent forScreen andHollywood! Early “Talkies” How It All Began — Movie Technology & Innovation Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904) Pioneers of Communication • Scott 3061; see also Scott 231 • Landing of Columbus from the Columbian Exposition issue A pioneer in motion studies, Muybridge exhibited moving picture sequences of animals and athletes taken with his “Zoopraxiscope” to a paying audience in the Zoopraxographical Hall at the 1893 Columbian Exposition. Although these brief (a few seconds each) moving picture views titled “The Science of Animal Locomotion” did not generate the profit Muybridge expected, the Hall can be considered the first “movie theater.” Thomas Alva Edison William Dickson Motion Pictures, (1847–1947) (1860–1935) 50th Anniversary Thomas A. Edison Pioneers of Communication Scott 926 Birth Centenary • Scott 945 Scott 3064 The first motion picture to be copyrighted Edison wrote in 1888, “I am experimenting Hired as Thomas Edison’s assistant in in the United States was Edison upon an instrument which does for the 1883, Dickson was the primary developer Kinetoscopic Record of a Sneeze (also eye what the phonograph does for the of the Kintograph camera and Kinetoscope known as Fred Ott’s Sneeze). Made January ear.” In April 1894 the first Kinetoscope viewer. The first prototype, using flexible 9, 1894, the 5-second, 48-frame film shows Parlour opened in New York City with film, was demonstrated at the lab to Fred Ott (one of Edison’s assistants) taking short features such as The Execution of visitors from the National Federation of a pinch of snuff and sneezing. -

Ruth Prawer Jhabvala's Adapted Screenplays

Absorbing the Worlds of Others: Ruth Prawer Jhabvala’s Adapted Screenplays By Laura Fryer Submitted in fulfilment of the requirements of a PhD degree at De Montfort University, Leicester. Funded by Midlands 3 Cities and the Arts and Humanities Research Council. June 2020 i Abstract Despite being a prolific and well-decorated adapter and screenwriter, the screenplays of Ruth Prawer Jhabvala are largely overlooked in adaptation studies. This is likely, in part, because her life and career are characterised by the paradox of being an outsider on the inside: whether that be as a European writing in and about India, as a novelist in film or as a woman in industry. The aims of this thesis are threefold: to explore the reasons behind her neglect in criticism, to uncover her contributions to the film adaptations she worked on and to draw together the fields of screenwriting and adaptation studies. Surveying both existing academic studies in film history, screenwriting and adaptation in Chapter 1 -- as well as publicity materials in Chapter 2 -- reveals that screenwriting in general is on the periphery of considerations of film authorship. In Chapter 2, I employ Sandra Gilbert’s and Susan Gubar’s notions of ‘the madwoman in the attic’ and ‘the angel in the house’ to portrayals of screenwriters, arguing that Jhabvala purposely cultivates an impression of herself as the latter -- a submissive screenwriter, of no threat to patriarchal or directorial power -- to protect herself from any negative attention as the former. However, the archival materials examined in Chapter 3 which include screenplay drafts, reveal her to have made significant contributions to problem-solving, characterisation and tone. -

+- Vimeo Link for ALL of Bruce Jackson's and Diane

Virtual February 9, 2021 (42:2) William A. Wellman: THE PUBLIC ENEMY (1931, 83 min) Spelling and Style—use of italics, quotation marks or nothing at all for titles, e.g.—follows the form of the sources. Cast and crew name hyperlinks connect to the individuals’ Wikipedia entries +- Vimeo link for ALL of Bruce Jackson’s and Diane Christian’s film introductions and post-film discussions in the Spring 2021 BFS Vimeo link for our introduction to The Public Enemy Zoom link for all Fall 2020 BFS Tuesday 7:00 PM post-screening discussions: Meeting ID: 925 3527 4384 Passcode: 820766 Selected for National Film Registry 1998 Directed by William A. Wellman Written by Kubec Glasmon and John Bright Produced by Darryl F. Zanuck which are 1958 Lafayette Escadrille, 1955 Blood Cinematography by Devereaux Jennings Alley, 1954 Track of the Cat, 1954 The High and the Film Editing by Edward M. McDermott Mighty, 1953 Island in the Sky, 1951 Westward the Makeup Department Perc Westmore Women, 1951 It's a Big Country, 1951 Across the Wide Missouri, 1949 Battleground, 1948 Yellow Sky, James Cagney... Tom Powers 1948 The Iron Curtain, 1947 Magic Town, 1945 Story Jean Harlow... Gwen Allen of G.I. Joe, 1945 This Man's Navy, 1944 Buffalo Bill, Edward Woods... Matt Doyle 1943 The Ox-Bow Incident, 1939 The Light That Joan Blondell... Mamie Failed, 1939 Beau Geste, 1938 Men with Wings, 1937 Donald Cook... Mike Powers Nothing Sacred, 1937 A Star Is Born, 1936 Tarzan Leslie Fenton... Nails Nathan Escapes, 1936 Small Town Girl, 1936 Robin Hood of Beryl Mercer.. -

PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Hollywood 65 Auction 65, Auction Date: 10/17/2014

26662 Agoura Road, Calabasas, CA 91302 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Hollywood 65 Auction 65, Auction Date: 10/17/2014 LOT ITEM PRICE PREMIUM 1 AUTO RACING AND CLASSIC AUTOS IN FILM (14) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $350 2 SEX IN CINEMA (55) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $4,500 3 LILLIAN GISH VINTAGE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPH BY HARTSOOK STUDIO. $200 4 COLLECTION OF (19) PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHS OF LUCILLE BALL, TALLULAH $325 BANKHEAD, THEDA BARA, JOAN CRAWFORD, AND OTHERS. 5 ANNA MAY WONG SIGNED PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPH BY CECIL BEATON. $4,000 6 MABEL NORMAND (7) SILENT-ERA VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $200 7 EARLY CHILD-STARS (11) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS INCLUDING OUR GANG AND $225 JACKIE COOGAN. 9 BARBARA LA MARR (3) VINTAGE PHOTOS INCLUDING ONE ON HER DEATHBED. $325 10 ALLA NAZIMOVA (4) VINTAGE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHS. $300 11 SILENT-FILM LEADING LADIES (13) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $200 13 SILENT-FILM LEADING MEN (10) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $200 14 PRE-CODE BLONDES (24) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $325 15 CHARLIE CHAPLIN AND PAULETTE GODDARD (2) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. $350 16 COLLECTION OF (12) OVERSIZE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHS OF RENÉE ADORÉE, $400 MARCELINE DAY, AND OTHERS. 17 COLLECTION OF (17) OVERSIZE PORTRAIT PHOTOGRAPHS OF EVELYN BRENT, $1,200 NANCY CARROLL, LILI DAMITA, MARLENE DIETRICH, MIRIAM HOPKINS, MARY PICKFORD, GINGER ROGERS, GLORIA SWANSON, FAY WRAY AND OTHERS. 18 MYRNA LOY (14) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS INCLUDING SEVERAL RARE $375 PRE-CODE IMAGES. Page 1 of 85 26662 Agoura Road, Calabasas, CA 91302 Tel: 310.859.7701 Fax: 310.859.3842 PRICES REALIZED DETAIL - Hollywood 65 Auction 65, Auction Date: 10/17/2014 LOT ITEM PRICE PREMIUM 19 PREMIUM SELECTION OF LEADING MEN (32) VINTAGE PHOTOGRAPHS. -

Personajes Legendarios En Un Mundo Globalizado. Las Relaciones Interculturales De La Mano Del Manga Drifters Legendary Figures in a Globalized World

Personajes legendarios en un mundo globalizado 159 Personajes legendarios en un mundo globalizado. Las relaciones interculturales de la mano del manga Drifters Legendary Figures in a Globalized World. Intercultural Relations through Drifters manga Claudia Bonillo Fernández 1 Resumen: El manga Drifters sigue a varios personajes históricos, de cualquier parte del mundo y época, que han sido trasladados a un mundo de fantasía en el momento de su muerte, donde podrán cumplir dos papeles: el de Drifters, encargados de salvar a la humanidad, o el de Ends, encargados de destruirla. La serie, fruto de la imaginación de Hirano Kōta, nos ofrece una visión novedosa de las relaciones interculturales que ocasionan considerables fricciones, pero también puntos de unión inesperados a pesar de la disparidad de mundos de los que los personajes provienen. Palabras clave: Hirano Kōta, manga, historia, diferencia cultural, semiología. Abstract: Drifters manga follows several historical characters, from different parts of the world and time, who have been transferred to a fantasy world at the time of their death. There they can fulfil two roles: to become either Drifters, with the responsibility for saving humanity, or Ends, responsible for destroying it. The series, created by the imagination of Hirano Kōta, offers an original vision of intercultural relationships that cause considerable friction, but also unexpected points of union despite the disparity of worlds from which the characters come. Keywords: Hirano Kōta, manga, history, culture difference, semiology. 1 [email protected] Neuróptica. Estudios sobre el cómic, segunda época, 1, Zaragoza, Prensas de la Universidad de Zaragoza, 2019 160 Claudia Bonillo El manga Drifters (Hirano, Kōta. -

WARNER ARCHIVE DVD COLLECTION – Informal Collection List As of Winter 2013

WARNER ARCHIVE DVD COLLECTION – informal collection list as of Winter 2013. For updated information or to arrange viewing, please e-mail [email protected]. Item # Title DVD8925 2 WEEKS IN ANOTHER TOWN [1962] DVD7519 20,000 YEARS IN SING SING [1933] DVD9691 24 HOURS TO KILL [1965] DVD7301 3 SAILORS AND A GIRL [1953] DVD8754 -30- [1959] DVD10749 5 TIME CHAMPION [2012] DVD9877 7 FACES OF DR. LAO [1963] DVD9174 ABBOTT AND COSTELLO MEET CAPTAIN KIDD [1952] DVD7192 ABDICATION, THE [1974] DVD7206 ABE LINCOLN IN ILLINOIS [1940] DVD7171 ABOVE AND BEYOND [1952] DVD7934 ABOVE SUSPICION [1943] DVD9781 ACROSS THE WIDE MISSOURI [1951] DVD7520 ACROSS TO SINGAPORE [1928] DVD7201 ACTRESS, THE [1953] DVD10743 ADA [1961] DVD8764 ADAM’S WOMAN [1969] DVD9634 ADVANCE TO THE REAR [1963] DVD9780 ADVENTURE [1945] DVD7191 ADVENTURES OF HUCKLEBERRY FINN, THE [1939] DVD7216 ADVENTURES OF MARK TWAIN, THE [1944] DVD7743 ADVENTURES OF ONE ESKIMO, THE [2009] DVD9976 AFFAIRS OF DOBIE GILLIS, THE [1953] DVD8554 AGATHA [1978] DVD10336 AGE OF CONSENT, THE [1932] DVD9136 AGE OF INNOCENCE, THE [1934] DVD7195 AH, WILDERNESS! [1935] DVD7669 AIRBORNE [1993] DVD9800 AKIRA KUROSAWA’S DREAMS [1990] DVD7226 AL CAPONE [1959] DVD9807 ALEX IN WONDERLAND [1970] DVD8845 ALIAS THE DOCTOR [1932] DVD8118 ALIBI IKE [1935] DVD10532 ALICE [THE COMPLETE FIRST SEASON] [DISC 1 OF 3] DVD10533 ALICE [THE COMPLETE FIRST SEASON] [DISC 2 OF 3] DVD10534 ALICE [THE COMPLETE FIRST SEASON] [DISC 3 OF 3] DVD10772 ALICE [THE COMPLETE SECOND SEASON] [DISC 1 OF 3] DVD10773 ALICE [THE COMPLETE SECOND SEASON] -

Irina Yusupova Vs. Mgm

THE PRINCESS ON THE WITNESS STAND: IRINA YUSUPOVA VS. MGM What does it cost to blur the line between fiction and reality? FILE UNDER: FASCINATING ROYAL AND NOBLE WOMEN WANT ME TO READ THIS POST TO YOU? CONTENTS: With a Friend Like This, Who Needs Enemies? | Meet Felix | Hooray for Hollywood | The Show Must Go On | Disputin’ | And the Oscar Goes To… | Lawyer Up | Stranger Than Fiction | “Monsters Out of My Head” HEN I WAS LITTLE, I never understood why W movies about real people featured the following disclaimer: “Any similarity to actual persons, living or dead, or actual events, is purely coincidental.” It was a blatant lie. Of course Elliott Ness in The Untouchables wasn’t made-up. Neither was Howard Hughes in The Aviator. So why does that disclaimer exist? Because of a series of bad decisions that can be traced back to – wait for it – Rasputin and the fall of the Russian empire. WITH A FRIEND LIKE THIS, WHO NEEDS ENEMIES? THIS ISN’T A STORY ABOUT Rasputin or his murder. But to understand what happened later, we need to start in pre-revolutionary Russia. In October of 1905, Tsar Nicholas II and Tsarina Alexandra met Grigori Efimovich Rasputin. He was a wandering holy man who claimed to have spiritual gifts, including the power to heal. GIRLINTHETIARA.COM | IRINA YUSUPOVA VS. MGM RASPUTIN BY AN UNKNOWN PHOTOGRAPHER, PUBLIC DOMAIN VIA WIKIMEDIA COMMONS. But he wasn’t the type of holy man who led a chaste, austere life. Nope. He drank and he chased women. He was arrogant and he was coarse. -

David Lean: DR. ZHIVAGO (1965, 197 Min.)

March 12, 2019 (XXXVIII:7) David Lean: DR. ZHIVAGO (1965, 197 min.) DIRECTOR David Lean WRITING Robert Bolt screenplay adapted from the Boris Pasternak novel PRODUCER Carlo Ponti MUSIC Maurice Jarre CINEMATOGRAPHY Freddie Young EDITING Norman Savage PRODUCTION DESIGN John Box ART DIRECTION Terence Marsh SET DECORATION Dario Simoni COSTUME DESIGN Phyllis Dalton The film permeated the 1966 Academy Awards, winning Oscars for Best Writing, Screenplay Based on Material from Another Medium (Robert Bolt), Best Cinematography, Color (Freddie Young), Best Art Direction-Set Decoration, Color (John Box, Terence Marsh, and Dario Simoni), Best Costume Design, Color (Phyllis Dalton), and Best Music, Score (Maurice Jarre). The Mark Eden...Engineer at Dam film also received Oscar nominations for Best Picture (Carlo Erik Chitty...Old Soldier Ponti), Best Actor in a Supporting Role (Tom Courtenay), Best Roger Maxwell...Beef-Faced Colonel Director (David Lean), Best Sound (A.W. Watkins, Franklin Wolf Frees...Delegate Milton), and Best Film Editing (Norman Savage). The film was Gwen Nelson...Female Janitor also nominated for the Cannes Palm d’Or. Lucy Westmore...Katya Lili Muráti...The Train Jumper (as Lili Murati) CAST Peter Madden...Political Officer Omar Sharif...Yuri Julie Christie...Lara DAVID LEAN (b. March 25, 1908 in Croydon, Surrey, England, Geraldine Chaplin...Tonya UK—d. April 16, 1991 (age 83) in London, England, UK) was Rod Steiger...Komarovsky an English film director (19 credits), producer, screenwriter (10 Alec Guinness...Yevgraf credits)