Angola and the Democratic Republic of Congo's Border from a Place Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Hybridization Between the Megasubspecies Cailliautii and Permista of the Green-Backed Woodpecker, Campethera Cailliautii

Le Gerfaut 77: 187–204 (1987) HYBRIDIZATION BETWEEN THE MEGASUBSPECIES CAILLIAUTII AND PERMISTA OF THE GREEN-BACKED WOODPECKER, CAMPETHERA CAILLIAUTII Alexandre Prigogine The two woodpeckers, Campethera cailliautii (with races nyansae, “fuel leborni”, loveridgei) and C. permista (with races togoensis, kaffensis) were long regarded as distinct species (Sclater, 1924; Chapin 1939). They are quite dissimi lar: permista has a plain green mantle and barred underparts, while cailliautii is characterized by clear spots on the upper side and black spots on the underpart. The possibility that they would be conspecific was however considered by van Someren in 1944. Later, van Someren and van Someren (1949) found that speci mens of C. permista collected in the Bwamba Forest tended strongly toward C. cailliautii nyansae and suggested again that permista and cailliautii may be con specific. Chapin (1952) formally treated permista as a subspecies of C. cailliautii, noting two intermediates from the region of Kasongo and Katombe, Zaire, and referring to a correspondence of Schouteden who confirmed the presence of other intermediates from Kasai in the collection of the MRAC (see Annex 2). Hall (1960) reported two intermediates from the Luau River and from near Vila Luso, Angola. Traylor (1963) noted intermediates from eastern Lunda. Pinto (1983) mentioned seven intermediates from Dundo, Mwaoka, Lake Carumbo and Cafunfo (Luango). Thus the contact zone between permista and nyansae extends from the region north-west of Lake Tanganyika to Angola, crossing Kasai, in Zaire. A second, shorter, contact zone may exist near the eastern border of Zaire, not far from the Equator. The map published by Short and Tarbaton (in Snow 1978) shows cailliautii from the Semliki Valley, on the Equator but I know of no speci mens of this woodpecker from this region. -

Tracing the Linguistic Origins of Slaves Leaving Angola, 1811-1848

From beyond the Kwango - Tracing the Linguistic Origins of Slaves Leaving Angola, 1811-1848 DOI http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/2236-463320161203 Badi Bukas-Yakabuul Resumo Atlanta First Presbyterian Church, O Rio Quango tem sido visto há muito tempo como o limite do acesso Atlanta - EUA dos traficantes de escravos às principais fontes de cativos no interior [email protected] de Angola, a maior região de embarque de escravos para as Américas. Contudo, não há estimativas sobre o tamanho e a distribuição dessa Daniel B. Domingues da Silva enorme migração. Este artigo examina registros de africanos libertados de Cuba e Serra Leoa disponíveis no Portal Origens Africanas para estimar University of Missouri, Columbia - o número de escravos provenientes daquela região em particular durante EUA o século XIX além da sua distribuição etnolingüística. Ele demonstra [email protected] que cerca de 21 porcento dos escravos transportados de Angola naquele período vieram de além Quango, sendo a maioria oriunda dos povos luba, canioque, e suaíli. O artigo também analisa as causas dessa migração, que ajudou a transformar a diáspora africana para as Américas, especialmente para o Brasil e Cuba. Abstract The Kwango River has long been viewed as the limit of the transatlantic traders’ access to the main sources of slaves in the interior of Angola, the principal region of slave embarkation to the Americas. However, no estimates of the size and distribution of this huge migration exist. This article examines records of liberated Africans from Cuba and Sierra Leone available on the African Origins Portal to estimate how many slaves came from that particular region in the nineteenth century as well as their ethnolinguistic distribution. -

Statoil-Environment Impact Study for Block 39

Technical Sheet Title: Environmental Impact Study for the Block 39 Exploratory Drilling Project. Client: Statoil Angola Block 39 AS Belas Business Park, Edifício Luanda 3º e 4º andar, Talatona, Belas Telefone: +244-222 640900; Fax: +244-222 640939. E-mail: [email protected] www.statoil.com Contractor: Holísticos, Lda. – Serviços, Estudos & Consultoria Rua 60, Casa 559, Urbanização Harmonia, Benfica, Luanda Telefone: +244-222 006938; Fax: +244-222 006435. E-mail: [email protected] www.holisticos.co.ao Date: August 2013 Environmental Impact Study for the Block 39 Exploratory Drilling Project TABLE OF CONTENTS 1. INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................... 1-1 1.1. BACKGROUND ............................................................................................................................. 1-1 1.2. PROJECT SITE .............................................................................................................................. 1-4 1.3. PURPOSE AND SCOPE OF THE EIS .................................................................................................... 1-5 1.4. AREAS OF INFLUENCE .................................................................................................................... 1-6 1.4.1. Directly Affected area ...................................................................................................... 1-7 1.4.2. Area of direct influence .................................................................................................. -

2016 Corporate Responsibility Report

southern africa strategic business unit 2016 corporate responsibility report Cautionary statement relevant to forward-looking information This corporate responsibility report contains forward-looking statements relating to the manner in which Chevron intends to conduct certain of its activities, based on management’s current plans and expectations. These statements are not promises or guarantees of future conduct or policy and are subject to a variety of uncertainties and other factors, many of which are beyond our control. Therefore, the actual conduct of our activities, including the development, implementation or continuation of any program, policy or initiative discussed or forecast in this report may differ materially in the future. The statements of intention in this report speak only as of the date of this report. Chevron undertakes no obligation to publicly update any statements in this report. As used in this report, the term “Chevron” and such terms as “the Company,” “the corporation,” “their,” “our,” “its,” “we”and “us” may refer to one or more of Chevron’s consolidated subsidiaries or affiliates or to all of them taken as a whole. All these terms are used for convenience only and are not intended as a precise description of any of the separate entities, each of which manages its own affairs. Prevnar 13 is a federally registered trademark of Wyeth LLC. Front cover: First grade students get ready for class at São José do Cluny School in Viana Municipality – Luanda. Fisherman standing by his stationed boat at Fishermen beach in Cabinda province. table of contents 1 A message from our managing director 4 Chevron in southern Africa 6 Environmental stewardship 8 Social investment 16 Workforce health and development 20 Human rights The SSCV Hermod as it prepares to lift the Mafumeira Sul WHP topsides from a barge. -

Africa Notes

Number 137 June 1992 CSISAFRICA NOTES A publication of the Center for Strategic and International Studies , Washington, D.C. Angola in Transition: The Cabinda Factor by Shawn McCormick In accordance with the Portuguese-mediated agreement signed by leaders of the governing Movimento Popular de Libertac;:ao de Angola (MPLA) .and the Uniao Nacional para a Independencia Total de Angola (UNIT A) in May 1991, the 16-year civil war that erupted in Angola as the country achieved independent statehood in 1975 has ended. Efforts to implement the second priority mandated in the agreement-national elections by late 1992-are being assisted by a range of international actors, including the United Nations, the United States, Russia, and Portugal. More than 12 parties are likely to participate in the elections (scheduled for September 29 and 30, 1992). The process of achieving a third key element of the agreement-demobilization of three-fourths of the two armies and integration of the remaining soldiers into a 50,000-strong national force-seems unlikely to conclude before elections are held. Although media attention focuses on developments and major players in the capital city of Luanda, where UNIT A has officially established a presence, analysts of the Angolan scene are according new attention to tiny Cabinda province (where an increasingly active separatist movement is escalating its pursuit of independence from Luanda) as "possibly Angola's last and most important battlefield." The significance of Cabinda-a 2,807-square-mile enclave along the Atlantic Ocean separated from Angola's other 17 contiguous provinces by a 25-mile strip of Zaire-lies in the fact that current offshore oil production, including that from the Takula and Malanga fields, totals more than 310,000 barrels per day (bpd). -

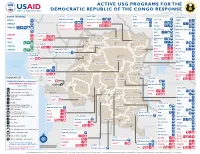

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS for the DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC of the CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20

ACTIVE USG PROGRAMS FOR THE DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO RESPONSE Last Updated 07/27/20 BAS-UELE HAUT-UELE ITURI S O U T H S U D A N COUNTRYWIDE NORTH KIVU OCHA IMA World Health Samaritan’s Purse AIRD Internews CARE C.A.R. Samaritan’s Purse Samaritan’s Purse IMA World Health IOM UNHAS CAMEROON DCA ACTED WFP INSO Medair FHI 360 UNICEF Samaritan’s Purse Mercy Corps IMA World Health NRC NORD-UBANGI IMC UNICEF Gbadolite Oxfam ACTED INSO NORD-UBANGI Samaritan’s WFP WFP Gemena BAS-UELE Internews HAUT-UELE Purse ICRC Buta SCF IOM SUD-UBANGI SUD-UBANGI UNHAS MONGALA Isiro Tearfund IRC WFP Lisala ACF Medair UNHCR MONGALA ITURI U Bunia Mercy Corps Mercy Corps IMA World Health G A EQUATEUR Samaritan’s NRC EQUATEUR Kisangani N Purse WFP D WFPaa Oxfam Boende A REPUBLIC OF Mbandaka TSHOPO Samaritan’s ATLANTIC NORTH GABON THE CONGO TSHUAPA Purse TSHOPO KIVU Lake OCEAN Tearfund IMA World Health Goma Victoria Inongo WHH Samaritan’s Purse RWANDA Mercy Corps BURUNDI Samaritan’s Purse MAI-NDOMBE Kindu Bukavu Samaritan’s Purse PROGRAM KEY KINSHASA SOUTH MANIEMA SANKURU MANIEMA KIVU WFP USAID/BHA Non-Food Assistance* WFP ACTED USAID/BHA Food Assistance** SA ! A IMA World Health TA N Z A N I A Kinshasa SH State/PRM KIN KASAÏ Lusambo KWILU Oxfam Kenge TANGANYIKA Agriculture and Food Security KONGO CENTRAL Kananga ACTED CRS Cash Transfers For Food Matadi LOMAMI Kalemie KASAÏ- Kabinda WFP Concern Economic Recovery and Market Tshikapa ORIENTAL Systems KWANGO Mbuji T IMA World Health KWANGO Mayi TANGANYIKA a KASAÏ- n Food Vouchers g WFP a n IMC CENTRAL y i k -

Colonialism and Its Socio-Politico and Economic Impact: a Case Study of the Colonized Congo Gulzar Ahmad & Muhamad Safeer Awan

Colonialism and its Socio-politico and Economic Impact: A Case study of the Colonized Congo Gulzar Ahmad & Muhamad Safeer Awan Abstract The exploitation of African Congo during colonial period is an interesting case study. From 1885 to 1908, it remained in the clutches of King Leopold II. During this period the Congo remained a victim of exploitation which has far sighted political, social and economic impacts. The Congo Free State was a large state in Central Africa which was in personal custody of King Leopold II. The socio-politico and economic study of the state reflects the European behaviour and colonial policy, a point of comparison with other colonial experiences. The analysis can be used to show that the abolition of the slave trade did not necessarily lead to a better experience for Africans at the hands of Europeans. It could also be used to illustrate the problems of our age. The social reformers, political leaders; literary writers and the champion of human rights have their own approaches and interpretations. Joseph Conrad is one of the writers who observed the situation and presented them in fictional and historical form in his books, Heart of Darkness, The Congo Diary, Notes on Life and Letters and Personal Record. In this paper a brief analysis is drawn about the colonialism and its socio-political and psychological impact in the historical perspectives. Keywords: Colonialism, Exploitation, Colonialism, Congo. Introduction The state of Congo, the heart of Africa, was colonized by Leopold II, king of the Belgium from 1885 to 1908. During this period it remained in the clutches of colonialism. -

Cycles Approved by OHRM for S

Consolidated list of duty stations approved by OHRM for rest and recuperation (R & R) (as of 1 July 2015) Duty Station Frequency R & R Destination AFGHANISTAN Entire country 6 weeks Dubai ALGERIA Tindouf 8 weeks Las Palmas BURKINA FASO Dori 12 weeks Ouagadougou BURUNDI Bujumbura, Gitega, Makamba, Ngozi 8 weeks Nairobi CENTRAL AFRICAN REPUBLIC Entire country 6 weeks Yaoundé CHAD Abeche, Farchana, Goré, Gozbeida, Mao, N’Djamena, Sarh 8 weeks Addis Ababa COLOMBIA Quibdo 12 weeks Bogota COTE D’IVOIRE Entire country except Abidjan and Yamoussoukro 8 weeks Accra DEMOCRATIC REPUBLIC OF THE CONGO Aru, Beni, Bukavu, Bunia, Butembo, Dungu, Goma, Kalemie, Mahagi, Uvira 6 weeks Entebbe Bili, Bandundu, Gemena, Kamina, Kananga, Kindu, Kisangani, Matadi, Mbandaka, Mbuji-Mayi 8 weeks Entebbe Lubumbashi 12 weeks Entebbe DEMOCRATIC PEOPLE’S REPUBLIC OF KOREA Pyongyang 8 weeks Beijing ETHIOPIA Kebridehar 6 weeks Addis Ababa Jijiga 8 weeks Addis Ababa GAZA Gaza (entire) 8 weeks Amman GUINEA Entire country 6 weeks Accra HAITI Entire country 8 weeks Santo Domingo INDONESIA Jayapura 12 weeks Jakarta IRAQ Baghdad, Basrah, Kirkuk, Dohuk 4 weeks Amman Erbil, Sulaymaniah 8 weeks Amman KENYA Dadaab, Wajir, Liboi 6 weeks Nairobi Kakuma 8 weeks Nairobi KYRGYZSTAN Osh 8 weeks Istanbul LIBERIA Entire country 8 weeks Accra LIBYA Entire country 6 weeks Malta MALI Gao, Kidal, Tesalit 4 weeks Dakar Tombouctou, Mopti 6 weeks Dakar Bamako, Kayes 8 weeks Dakar MYANMAR Sittwe 8 weeks Yangon Myitkyina (Kachin State) 12 weeks Yangon NEPAL Bharatpur, Bidur, Charikot, Dhunche, -

Inventário Florestal Nacional, Guia De Campo Para Recolha De Dados

Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais de Angola Inventário Florestal Nacional Guia de campo para recolha de dados . NFMA Working Paper No 41/P– Rome, Luanda 2009 Monitorização e Avaliação de Recursos Florestais Nacionais As florestas são essenciais para o bem-estar da humanidade. Constitui as fundações para a vida sobre a terra através de funções ecológicas, a regulação do clima e recursos hídricos e servem como habitat para plantas e animais. As florestas também fornecem uma vasta gama de bens essenciais, tais como madeira, comida, forragem, medicamentos e também, oportunidades para lazer, renovação espiritual e outros serviços. Hoje em dia, as florestas sofrem pressões devido ao aumento de procura de produtos e serviços com base na terra, o que resulta frequentemente na degradação ou transformação da floresta em formas insustentáveis de utilização da terra. Quando as florestas são perdidas ou severamente degradadas. A sua capacidade de funcionar como reguladores do ambiente também se perde. O resultado é o aumento de perigo de inundações e erosão, a redução na fertilidade do solo e o desaparecimento de plantas e animais. Como resultado, o fornecimento sustentável de bens e serviços das florestas é posto em perigo. Como resposta do aumento de procura de informações fiáveis sobre os recursos de florestas e árvores tanto ao nível nacional como Internacional l, a FAO iniciou uma actividade para dar apoio à monitorização e avaliação de recursos florestais nationais (MANF). O apoio à MANF inclui uma abordagem harmonizada da MANF, a gestão de informação, sistemas de notificação de dados e o apoio à análise do impacto das políticas no processo nacional de tomada de decisão. -

The Botanical Exploration of Angola by Germans During the 19Th and 20Th Centuries, with Biographical Sketches and Notes on Collections and Herbaria

Blumea 65, 2020: 126–161 www.ingentaconnect.com/content/nhn/blumea RESEARCH ARTICLE https://doi.org/10.3767/blumea.2020.65.02.06 The botanical exploration of Angola by Germans during the 19th and 20th centuries, with biographical sketches and notes on collections and herbaria E. Figueiredo1, *, G.F. Smith1, S. Dressler 2 Key words Abstract A catalogue of 29 German individuals who were active in the botanical exploration of Angola during the 19th and 20th centuries is presented. One of these is likely of Swiss nationality but with significant links to German Angola settlers in Angola. The catalogue includes information on the places of collecting activity, dates on which locations botanical exploration were visited, the whereabouts of preserved exsiccata, maps with itineraries, and biographical information on the German explorers collectors. Initial botanical exploration in Angola by Germans was linked to efforts to establish and expand Germany’s plant collections colonies in Africa. Later exploration followed after some Germans had settled in the country. However, Angola was never under German control. The most intense period of German collecting activity in this south-tropical African country took place from the early-1870s to 1900. Twenty-four Germans collected plant specimens in Angola for deposition in herbaria in continental Europe, mostly in Germany. Five other naturalists or explorers were active in Angola but collections have not been located under their names or were made by someone else. A further three col- lectors, who are sometimes cited as having collected material in Angola but did not do so, are also briefly discussed. Citation: Figueiredo E, Smith GF, Dressler S. -

UC Berkeley GAIA Books

UC Berkeley GAIA Books Title Crude Existence: The Politics of Oil in Northern Angola Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0n17g0n0 Journal GAIA Books, 12 Author Reed, Kristin Publication Date 2009-11-01 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Crude Existence: Environment and the Politics of Oil in Northern Angola Kristin Reed Published in association with University of California Press Description: After decades of civil war and instability, the African country of Angola is experiencing a spectacular economic boom thanks to its most valuable natural resource: oil. But oil extraction—both on and offshore—is a toxic remedy for the country’s economic ills, with devastating effects on both the environment and traditional livelihoods. Focusing on the everyday realities of people living in the extraction zones, Kristin Reed explores the exclusion, degradation, and violence that are the bitter fruits of petro-capitalism in Angola. She emphasizes the failure of corporate initiatives to offset the destructive effects of their activities. Author: Kristin Reed holds a Ph.D. in Environmental Science, Policy, and Management from the University of California, Berkeley. She is a program consultant to humanitarian and environmental nonprofit organizations. Review: “An absolutely necessary work of political ecology. Centering on the polluted, impoverished coastal communities of northwest Angola, Crude Existence convincingly shows how the ‘curse of oil’ in extractive regions is a curse of political -

Mobile Money in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Market Insights on Consumer Needs and Opportunities in Payments and Financial Services

Mobile Money in the Democratic Republic of Congo: Market insights on consumer needs and opportunities in payments and financial services July 2013 MMU_DRCongo_Report_200613.indd 1 20/06/2013 17:33 Contents 3 Executive Summary 5 Project overview and introduction 7 Key findings 7 Market context: use of financial services limited in the DRC 8 Preference and prevalence of financial services in the DRC 8 — Insights from household decision-makers 18 — Insight from small business owners 20 Opportunities and challenges for mobile operators moving into mobile money 27 Conclusions and recommendations 29 Appendix 1. Household decision-makers’ survey: sample demographics 31 Appendix 2: Research methodology Figures 8 Figure 1 – Percentage who received a transfer in each province 9 Figure 2 – Destination of transfers sent and origins of transfers received 10 Figure 3 – Percentage who sent money for each reason “most often” 10 Figure 4 – Percentage who received money for each reason “most often” 11 Figure 5 – Percentage who used each method to send money in previous three months 12 Figure 6 – Reasons for using each transfer service (Percentage for each) 13 Figure 7 – Percentage who paid each type of bill in the previous three months 14 Figure 8 – Of those who had paid a bill, the percentage who had paid each type of bill in the previous three months, by province 15 Figure 9 – Percentage of each sector who received a salary or wage payment in the previous three months 16 Figure 10 – Reasons respondents save money 16 Figure 11 – Of the households who