The Online Library of Liberty Classics in the History Of

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

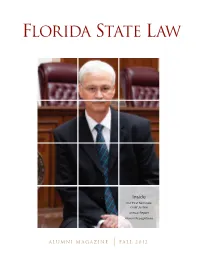

Fall 2012 Florida State Law Magazine

FLORIDA STATE LAW Inside Our First Seminole Chief Justice Annual Report Alumni Recognitions ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2012 Message from the Dean Jobs, Alumni, Students and Admissions Players in the Jobs Market Admissions and Rankings This summer, the Wall Street The national press has highlighted the related phenomena Journal reported that we are the of the tight legal job market and rising student indebtedness. nation’s 25th best law school when it More prospective applicants are asking if a law degree is worth comes to placing our new graduates the cost, and law school applications are down significantly. in jobs that require law degrees. Just Ours have fallen by approximately 30% over the past two years. this month, Law School Transparency Moreover, our “yield” rate has gone down, meaning that fewer ranked us the nation’s 26th best law students are accepting our offers of admission. Our research school in terms of overall placement makes clear: prime competitor schools can offer far more score, and Florida’s best. Our web generous scholarship packages. To attract the top students, page includes more detailed information on our placement we must limit our enrollment and increase scholarship awards. outcomes. In short, we rank very high nationally in terms We are working with our university administration to limit of the number of students successfully placed. Although our our enrollment, which of course has financial implications average starting salary of $58,650 is less than those at the na- both for the law school and for the central university. It is tion’s most elite private law schools, so is our average student also imperative to increase our endowment in a way that will indebtedness, which is $73,113. -

Reform of the Elected Judiciary in Boss Tweed’S New York

File: 3 Lerner - Corrected from Soft Proofs.doc Created on: 10/1/2007 11:25:00 PM Last Printed: 10/7/2007 6:34:00 PM 2007] 109 FROM POPULAR CONTROL TO INDEPENDENCE: REFORM OF THE ELECTED JUDICIARY IN BOSS TWEED’S NEW YORK Renée Lettow Lerner* INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 111 I. THE CONSTITUTION OF 1846: POPULAR CONTROL...................... 114 II. “THE THREAT OF HOPELESS BARBARISM”: PROBLEMS WITH THE NEW YORK JUDICIARY AND LEGAL SYSTEM AFTER THE CIVIL WAR .................................................. 116 A. Judicial Elections............................................................ 118 B. Abuse of Injunctive Powers............................................. 122 C. Patronage Problems: Referees and Receivers................ 123 D. Abuse of Criminal Justice ............................................... 126 III. THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1867-68: JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE............................................................. 130 A. Participation of the Bar at the Convention..................... 131 B. Natural Law Theories: The Law as an Apolitical Science ................................... 133 C. Backlash Against the Populist Constitution of 1846....... 134 D. Desire to Lengthen Judicial Tenure................................ 138 E. Ratification of the Judiciary Article................................ 143 IV. THE BAR’S REFORM EFFORTS AFTER THE CONVENTION ............ 144 A. Railroad Scandals and the Times’ Crusade.................... 144 B. Founding -

Project Gutenberg's a Popular History of Ireland V2, by Thomas D'arcy Mcgee #2 in Our Series by Thomas D'arcy Mcgee

Project Gutenberg's A Popular History of Ireland V2, by Thomas D'Arcy McGee #2 in our series by Thomas D'Arcy McGee Copyright laws are changing all over the world. Be sure to check the copyright laws for your country before downloading or redistributing this or any other Project Gutenberg eBook. This header should be the first thing seen when viewing this Project Gutenberg file. Please do not remove it. Do not change or edit the header without written permission. Please read the "legal small print," and other information about the eBook and Project Gutenberg at the bottom of this file. Included is important information about your specific rights and restrictions in how the file may be used. You can also find out about how to make a donation to Project Gutenberg, and how to get involved. **Welcome To The World of Free Plain Vanilla Electronic Texts** **eBooks Readable By Both Humans and By Computers, Since 1971** *****These eBooks Were Prepared By Thousands of Volunteers!***** Title: A Popular History of Ireland V2 From the earliest period to the emancipation of the Catholics Author: Thomas D'Arcy McGee Release Date: October, 2004 [EBook #6633] [Yes, we are more than one year ahead of schedule] [This file was first posted on January 6, 2003] Edition: 10 Language: English Character set encoding: ASCII *** START OF THE PROJECT GUTENBERG EBOOK A POPULAR HISTORY OF IRELAND *** This etext was produced by Gardner Buchanan with help from Charles Aldarondo and the Online Distributed Proofreading Team. A Popular History of Ireland: from the Earliest Period to the Emancipation of the Catholics by Thomas D'Arcy McGee In Two Volumes Volume II CONTENTS--VOL. -

The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof, 67 Fla

Florida Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 5 Article 2 March 2016 The urS prising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof John Leubsdorf Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation John Leubsdorf, The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof, 67 Fla. L. Rev. 1569 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol67/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leubsdorf: The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Pro THE SURPRISING HISTORY OF THE PREPONDERANCE STANDARD OF CIVIL PROOF John Leubsdorf * Abstract Although much has been written on the history of the requirement of proof of crimes beyond a reasonable doubt, this is the first study to probe the history of its civil counterpart, proof by a preponderance of the evidence. It turns out that the criminal standard did not diverge from a preexisting civil standard, but vice versa. Only in the late eighteenth century, after lawyers and judges began speaking of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, did references to the preponderance standard begin to appear. Moreover, U.S. judges did not start to instruct juries about the preponderance standard until the mid-nineteenth century, and English judges not until after that. The article explores these developments and their causes with the help of published trial transcripts and newspaper reports that have only recently become accessible. -

Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church Of

1 Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church of England in Restoration England, 1660-1688 David Kearns Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 2 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. David Kearns 29/06/2019 3 Authorship Attribution Statement This thesis contains material published in David Kearns, ‘Sovereignty and Common Law Judicial Office in Taylor’s Case (1675)’, Law and History Review, 37:2 (2019), 397-429, and material to be published in David Kearns and Ryan Walter, ‘Office, Political Theory, and the Political Theorist’, The Historical Journal (forthcoming). The research for these articles was undertaken as part of the research for this thesis. I am the sole author of the first article and sole author of section I of the co-authored article, and it is the research underpinning section I that appears in the thesis. David Kearns 29/06/2019 As supervisor for the candidature upon which this thesis is based, I can confirm that the authorship attribution statements above are correct. Andrew Fitzmaurice 29/06/2019 4 Acknowledgements Many debts have been incurred in the writing of this thesis, and these acknowledgements must necessarily be a poor repayment for the assistance that has made it possible. -

Cromwellian Anger Was the Passage in 1650 of Repressive Friends'

Cromwelliana The Journal of 2003 'l'ho Crom\\'.Oll Alloooluthm CROMWELLIANA 2003 l'rcoklcnt: Dl' llAlUW CO\l(IA1© l"hD, t'Rl-llmS 1 Editor Jane A. Mills Vice l'l'csidcnts: Right HM Mlchncl l1'oe>t1 l'C Profcssot·JONN MOlUUU.., Dl,llll, F.13A, FlU-IistS Consultant Peter Gaunt Professor lVAN ROOTS, MA, l~S.A, FlU~listS Professor AUSTIN WOOLll'YCH. MA, Dlitt, FBA CONTENTS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA PAT BARNES AGM Lecture 2003. TREWIN COPPLESTON, FRGS By Dr Barry Coward 2 Right Hon FRANK DOBSON, MF Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS 350 Years On: Cromwell and the Long Parliament. Honorary Secretary: MICHAEL BYRD By Professor Blair Worden 16 5 Town Farm Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEl 1 3SG Learning the Ropes in 'His Own Fields': Cromwell's Early Sieges in the East Honorary Treasurer: DAVID SMITH Midlands. 3 Bowgrave Copse, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 2NL By Dr Peter Gaunt 27 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Writings and Sources VI. Durham University: 'A Pious and laudable work'. By Jane A Mills · Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan 40 statesman, and to encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is neither political nor sectarian, its aims being The Revolutionary Navy, 1648-1654. essentially historical. The Association seeks to advance its aims in a variety of By Professor Bernard Capp 47 ways, which have included: 'Ancient and Familiar Neighbours': England and Holland on the eve of the a. -

John Sadler (1615-1674) Religion, Common Law, and Reason in Early Modern England

THE PETER TOMASSI ESSAY john sadler (1615-1674) religion, common law, and reason in early modern england pranav kumar jain, university of chicago (2015) major problems. First, religion—the pivotal force I. INTRODUCTION: RE-THINKING EARLY that shaped nearly every aspect of life in seventeenth- MODERN COMMON LAW century England—has received very little attention in ost histories of Early Modern English most accounts of common law. As I will show in the common law focus on a very specific set next section, either religion is not mentioned at all of individuals, namely Justices Edward or treated as parallel to common law. In other words, MCoke and Matthew Hale, Sir Francis Bacon, Sir Henry historians have generally assumed a disconnect Finch, Sir John Doddridge, and-very recently-John between religion and common law during this Selden.i The focus is partly explained by the immense period. Even works that have attempted to examine influence most of these individuals exercised upon the intersection of religion and common law have the study and practice of common law during the argued that the two generally existed in harmony seventeenth century.ii Moreover, according to J.W. or even as allies in service to political motives. Tubbs, such a focus is unavoidable because a great The possibility of tensions between religion and majority of common lawyers left no record of their common law has not been considered at all. Second, thoughts.1 It is my contention that Tubbs’ view is most historians have failed to consider emerging unwarranted. Even if it is impossible to reconstruct alternative ways in which seventeenth-century the thoughts of a vast majority of common lawyers, common lawyers conceptualized the idea of reason there is no reason to limit our studies of common as a foundational pillar of English common law. -

2018 Table of Contents I. Articles

AALS Law and Religion Section Annual Bibliography: 2018 Table of Contents I. Journal Articles ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 III. Special Journal Issues ............................................................................................................................................ 7 III. Monographs ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 IV. Edited Volumes ...................................................................................................................................................... 11 I. Articles Zoe Adams & John Olusegun Adenitire, Ideological Neutrality in the Workplace, 81 MODERN L. REV. 348 (2018) Ryan T. Anderson, A Brave New World of Transgender Policy, 41 HARV. J. L. & PUBLIC POLICY 309 (2018) Ruth Arlow, Kuteh v. Dartfod and Gravesham NHS Trust, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 113 (2018) Ruth Arlow, The Reverend J. Gould v. Trustees of St. John’s, Downshire Hill, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 241 (2018) Ruth Arlow, Scott v. Stevenson & Reid Ltd: Northern Ireland Fair Employment Tribunal, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 245 (2018) Giorgia Baldi, Re-conceptualizing Equality in the Work Place: A Reading of the Latest CJEU’s Opinions over the Practice of Veiling, 7 OXFORD J. L. & RELIG. 296 (2018) Luke Beck, The Role of Religion in the Law of Royal Succession in Canada and -

Piety, Sparkling Wit, and Dauntless Courage of Her People, Have at Last Brought Her Forth Like

A Popular History of Ireland: from the Earliest Period to the Emancipation of the Catholics by Thomas D'Arcy McGee In Two Volumes Volume I PUBLISHERS' PREFACE. Ireland, lifting herself from the dust, drying her tears, and proudly demanding her legitimate place among the nations of the earth, is a spectacle to cause immense progress in political philosophy. Behold a nation whose fame had spread over all the earth ere the flag of England had come into existence. For 500 years her life has been apparently extinguished. The fiercest whirlwind of oppression that ever in the wrath of God was poured upon the children of disobedience had swept over her. She was an object of scorn and contempt to her subjugator. Only at times were there any signs of life--an occasional meteor flash that told of her olden spirit--of her deathless race. Degraded and apathetic as this nation of Helots was, it is not strange that political philosophy, at all times too Sadducean in its principles, should ask, with a sneer, "Could these dry bones live?" The fulness of time has come, and with one gallant sunward bound the "old land" comes forth into the political day to teach these lessons, that Right must always conquer Might in the end--that by a compensating principle in the nature of things, Repression creates slowly, but certainly, a force for its overthrow. Had it been possible to kill the Irish Nation, it had long since ceased to exist. But the transmitted qualities of her glorious children, who were giants in intellect, virtue, and arms for 1500 years before Alfred the Saxon sent the youth of his country to Ireland in search of knowledge with which to civilize his people,--the legends, songs, and dim traditions of this glorious era, and the irrepressiblewww.genealogyebooks.com piety, sparkling wit, and dauntless courage of her people, have at last brought her forth like. -

Friends Though Divided a Tale of the Civil War by G

FRIENDS THOUGH DIVIDED A TALE OF THE CIVIL WAR BY G. A. HENTY AUTHOR OF "IN TIMES OF PERIL," "THE YOUNG FRANCTIREURS," "THE YOUNG BUGLERS," ETC, ETC. PREFACE My dear lads: Although so long a time has elapsed since the great civil war in England, men are still almost as much divided as they were then as to the merits of the quarrel, almost as warm partisans of the one side or the other. Most of you will probably have formed an opinion as to the rights of the case, either from your own reading, or from hearing the views of your elders. For my part, I have endeavored to hold the scales equally, to relate historical facts with absolute accuracy, and to show how much of right and how much of wrong there was upon either side. Upon the one hand, the king by his instability, bad faith, and duplicity alienated his best friends, and drove the Commons to far greater lengths than they had at first dreamed of. Upon the other hand, the struggle, begun only to win constitutional rights, ended—owing to the ambition, fanaticism, and determination to override all rights and all opinions save their own, of a numerically insignificant minority of the Commons, backed by the strength of the army—in the establishment of the most complete despotism England has ever seen. It may no doubt be considered a failing on my part that one of my heroes has a very undue preponderance of adventure over the other. This I regret; but after the scale of victory turned, those on the winning side had little to do or to suffer, and one's interest is certainly with the hunted fugitive, or the slave in the Bermudas, rather than with the prosperous and well-to-do citizen. -

Friends Acquisitions 1964-2018

Acquired with the Aid of the Friends Manuscripts 1964: Letter from John Dury (1596-1660) to the Evangelical Assembly at Frankfurt-am- Main, 6 August 1633. The letter proposes a general assembly of the evangelical churches. 1966: Two letters from Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Nicholas of Lucca, 1413. Letter from Robert Hallum, Bishop of Salisbury concerning Nicholas of Lucca, n.d. 1966: Narrative by Leonardo Frescobaldi of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1384. 1966: Survey of church goods in 33 parishes in the hundreds of Blofield and Walsham, Norfolk, 1549. 1966: Report of a debate in the House of Commons, 27 February 1593. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Petition to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners by Miles Coverdale and others, 1565. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Correspondence and papers of Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885), Bishop of Lincoln. 1968: Letter from John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, to John Boys, 1599. 1968: Correspondence and papers of William Howley (1766-1848), Archbishop of Canterbury. 1969: Papers concerning the divorce of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. 1970: Papers of Richard Bertie, Marian exile in Wesel, 1555-56. 1970: Notebook of the Nonjuror John Leake, 1700-35. Including testimony concerning the birth of the Old Pretender. 1971: Papers of Laurence Chaderton (1536?-1640), puritan divine. 1971: Heinrich Bullinger, History of the Reformation. Sixteenth century copy. 1971: Letter from John Davenant, Bishop of Salisbury, to a minister of his diocese [1640]. 1971: Letter from John Dury to Mr. Ball, Preacher of the Gospel, 1639. 1972: ‘The examination of Valentine Symmes and Arthur Tamlin, stationers, … the Xth of December 1589’. -

Oneillormondchap00coffuoft.Pdf

O'NEILL & ORMOND A CHAPTER IN IRISH HISTORY O'NEILL & ORMOND A CHAPTER IN IRISH HISTORY BY DIARMID COFFEY 1^ MAUNSEL & COMPANY, LTD. DUBLIN AND LONDON 1914 All rights reserved. TO ERSKINE GUILDERS PREFACE THE history of Ireland from 1641 to 1653 is divided into three great episodes: the rising of 1641, the Confederation of Kilkenny, and the Cromwellian Conquest of Ireland. Ireland has never been the fighting ground of more parties and factions than she was in this period. It is therefore difficult to preserve the unity of the narra- tive, which must embrace a body constantly changing its purpose, and to show some continuity in what is often an apparently aimless maze of intrigue. This will serve to explain the title I have chosen " for my book, O'Neill and Ormond." Owen Roe O'Neill and James, Earl of Ormond stand out clearly as the leading figures of the time. They are strongly contrasted. O'Neill, the leader of the Irish, con- stantly struggling against every kind of difficulty, a strong, determined man, whose only aim is the ad- vancement and freedom of his people, falls a victim to faction and self-interest. The history of Owen Roe O'Neill is like the history of every great Irishman who has worked for his country a desperate struggle against overwhelming odds, only to end in death when the cause for which he has been fighting is lost and every hope of helping his country seems extinguished. Ormond, on the other hand, is the great English governor. He may have cared for Ireland, but he certainly cared more for the King and all that he stood for.