Sir Matthew Hale

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

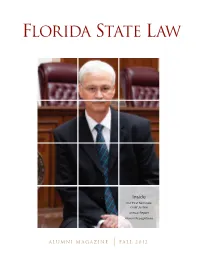

Fall 2012 Florida State Law Magazine

FLORIDA STATE LAW Inside Our First Seminole Chief Justice Annual Report Alumni Recognitions ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2012 Message from the Dean Jobs, Alumni, Students and Admissions Players in the Jobs Market Admissions and Rankings This summer, the Wall Street The national press has highlighted the related phenomena Journal reported that we are the of the tight legal job market and rising student indebtedness. nation’s 25th best law school when it More prospective applicants are asking if a law degree is worth comes to placing our new graduates the cost, and law school applications are down significantly. in jobs that require law degrees. Just Ours have fallen by approximately 30% over the past two years. this month, Law School Transparency Moreover, our “yield” rate has gone down, meaning that fewer ranked us the nation’s 26th best law students are accepting our offers of admission. Our research school in terms of overall placement makes clear: prime competitor schools can offer far more score, and Florida’s best. Our web generous scholarship packages. To attract the top students, page includes more detailed information on our placement we must limit our enrollment and increase scholarship awards. outcomes. In short, we rank very high nationally in terms We are working with our university administration to limit of the number of students successfully placed. Although our our enrollment, which of course has financial implications average starting salary of $58,650 is less than those at the na- both for the law school and for the central university. It is tion’s most elite private law schools, so is our average student also imperative to increase our endowment in a way that will indebtedness, which is $73,113. -

Reform of the Elected Judiciary in Boss Tweed’S New York

File: 3 Lerner - Corrected from Soft Proofs.doc Created on: 10/1/2007 11:25:00 PM Last Printed: 10/7/2007 6:34:00 PM 2007] 109 FROM POPULAR CONTROL TO INDEPENDENCE: REFORM OF THE ELECTED JUDICIARY IN BOSS TWEED’S NEW YORK Renée Lettow Lerner* INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 111 I. THE CONSTITUTION OF 1846: POPULAR CONTROL...................... 114 II. “THE THREAT OF HOPELESS BARBARISM”: PROBLEMS WITH THE NEW YORK JUDICIARY AND LEGAL SYSTEM AFTER THE CIVIL WAR .................................................. 116 A. Judicial Elections............................................................ 118 B. Abuse of Injunctive Powers............................................. 122 C. Patronage Problems: Referees and Receivers................ 123 D. Abuse of Criminal Justice ............................................... 126 III. THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1867-68: JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE............................................................. 130 A. Participation of the Bar at the Convention..................... 131 B. Natural Law Theories: The Law as an Apolitical Science ................................... 133 C. Backlash Against the Populist Constitution of 1846....... 134 D. Desire to Lengthen Judicial Tenure................................ 138 E. Ratification of the Judiciary Article................................ 143 IV. THE BAR’S REFORM EFFORTS AFTER THE CONVENTION ............ 144 A. Railroad Scandals and the Times’ Crusade.................... 144 B. Founding -

The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof, 67 Fla

Florida Law Review Volume 67 | Issue 5 Article 2 March 2016 The urS prising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof John Leubsdorf Follow this and additional works at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr Part of the Evidence Commons Recommended Citation John Leubsdorf, The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Proof, 67 Fla. L. Rev. 1569 (2016). Available at: http://scholarship.law.ufl.edu/flr/vol67/iss5/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by UF Law Scholarship Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Florida Law Review by an authorized administrator of UF Law Scholarship Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Leubsdorf: The Surprising History of the Preponderance Standard of Civil Pro THE SURPRISING HISTORY OF THE PREPONDERANCE STANDARD OF CIVIL PROOF John Leubsdorf * Abstract Although much has been written on the history of the requirement of proof of crimes beyond a reasonable doubt, this is the first study to probe the history of its civil counterpart, proof by a preponderance of the evidence. It turns out that the criminal standard did not diverge from a preexisting civil standard, but vice versa. Only in the late eighteenth century, after lawyers and judges began speaking of proof beyond a reasonable doubt, did references to the preponderance standard begin to appear. Moreover, U.S. judges did not start to instruct juries about the preponderance standard until the mid-nineteenth century, and English judges not until after that. The article explores these developments and their causes with the help of published trial transcripts and newspaper reports that have only recently become accessible. -

Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church Of

1 Common Law Judicial Office, Sovereignty, and the Church of England in Restoration England, 1660-1688 David Kearns Faculty of Arts and Social Sciences The University of Sydney A thesis submitted to fulfil requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy 2019 2 This is to certify that to the best of my knowledge, the content of this thesis is my own work. This thesis has not been submitted for any degree or other purposes. I certify that the intellectual content of this thesis is the product of my own work and that all the assistance received in preparing this thesis and sources have been acknowledged. David Kearns 29/06/2019 3 Authorship Attribution Statement This thesis contains material published in David Kearns, ‘Sovereignty and Common Law Judicial Office in Taylor’s Case (1675)’, Law and History Review, 37:2 (2019), 397-429, and material to be published in David Kearns and Ryan Walter, ‘Office, Political Theory, and the Political Theorist’, The Historical Journal (forthcoming). The research for these articles was undertaken as part of the research for this thesis. I am the sole author of the first article and sole author of section I of the co-authored article, and it is the research underpinning section I that appears in the thesis. David Kearns 29/06/2019 As supervisor for the candidature upon which this thesis is based, I can confirm that the authorship attribution statements above are correct. Andrew Fitzmaurice 29/06/2019 4 Acknowledgements Many debts have been incurred in the writing of this thesis, and these acknowledgements must necessarily be a poor repayment for the assistance that has made it possible. -

Cromwellian Anger Was the Passage in 1650 of Repressive Friends'

Cromwelliana The Journal of 2003 'l'ho Crom\\'.Oll Alloooluthm CROMWELLIANA 2003 l'rcoklcnt: Dl' llAlUW CO\l(IA1© l"hD, t'Rl-llmS 1 Editor Jane A. Mills Vice l'l'csidcnts: Right HM Mlchncl l1'oe>t1 l'C Profcssot·JONN MOlUUU.., Dl,llll, F.13A, FlU-IistS Consultant Peter Gaunt Professor lVAN ROOTS, MA, l~S.A, FlU~listS Professor AUSTIN WOOLll'YCH. MA, Dlitt, FBA CONTENTS Professor BLAIR WORDEN, FBA PAT BARNES AGM Lecture 2003. TREWIN COPPLESTON, FRGS By Dr Barry Coward 2 Right Hon FRANK DOBSON, MF Chairman: Dr PETER GAUNT, PhD, FRHistS 350 Years On: Cromwell and the Long Parliament. Honorary Secretary: MICHAEL BYRD By Professor Blair Worden 16 5 Town Farm Close, Pinchbeck, near Spalding, Lincolnshire, PEl 1 3SG Learning the Ropes in 'His Own Fields': Cromwell's Early Sieges in the East Honorary Treasurer: DAVID SMITH Midlands. 3 Bowgrave Copse, Abingdon, Oxon, OX14 2NL By Dr Peter Gaunt 27 THE CROMWELL ASSOCIATION was founded in 1935 by the late Rt Hon Writings and Sources VI. Durham University: 'A Pious and laudable work'. By Jane A Mills · Isaac Foot and others to commemorate Oliver Cromwell, the great Puritan 40 statesman, and to encourage the study of the history of his times, his achievements and influence. It is neither political nor sectarian, its aims being The Revolutionary Navy, 1648-1654. essentially historical. The Association seeks to advance its aims in a variety of By Professor Bernard Capp 47 ways, which have included: 'Ancient and Familiar Neighbours': England and Holland on the eve of the a. -

John Sadler (1615-1674) Religion, Common Law, and Reason in Early Modern England

THE PETER TOMASSI ESSAY john sadler (1615-1674) religion, common law, and reason in early modern england pranav kumar jain, university of chicago (2015) major problems. First, religion—the pivotal force I. INTRODUCTION: RE-THINKING EARLY that shaped nearly every aspect of life in seventeenth- MODERN COMMON LAW century England—has received very little attention in ost histories of Early Modern English most accounts of common law. As I will show in the common law focus on a very specific set next section, either religion is not mentioned at all of individuals, namely Justices Edward or treated as parallel to common law. In other words, MCoke and Matthew Hale, Sir Francis Bacon, Sir Henry historians have generally assumed a disconnect Finch, Sir John Doddridge, and-very recently-John between religion and common law during this Selden.i The focus is partly explained by the immense period. Even works that have attempted to examine influence most of these individuals exercised upon the intersection of religion and common law have the study and practice of common law during the argued that the two generally existed in harmony seventeenth century.ii Moreover, according to J.W. or even as allies in service to political motives. Tubbs, such a focus is unavoidable because a great The possibility of tensions between religion and majority of common lawyers left no record of their common law has not been considered at all. Second, thoughts.1 It is my contention that Tubbs’ view is most historians have failed to consider emerging unwarranted. Even if it is impossible to reconstruct alternative ways in which seventeenth-century the thoughts of a vast majority of common lawyers, common lawyers conceptualized the idea of reason there is no reason to limit our studies of common as a foundational pillar of English common law. -

2018 Table of Contents I. Articles

AALS Law and Religion Section Annual Bibliography: 2018 Table of Contents I. Journal Articles ........................................................................................................................................................... 1 III. Special Journal Issues ............................................................................................................................................ 7 III. Monographs ............................................................................................................................................................... 9 IV. Edited Volumes ...................................................................................................................................................... 11 I. Articles Zoe Adams & John Olusegun Adenitire, Ideological Neutrality in the Workplace, 81 MODERN L. REV. 348 (2018) Ryan T. Anderson, A Brave New World of Transgender Policy, 41 HARV. J. L. & PUBLIC POLICY 309 (2018) Ruth Arlow, Kuteh v. Dartfod and Gravesham NHS Trust, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 113 (2018) Ruth Arlow, The Reverend J. Gould v. Trustees of St. John’s, Downshire Hill, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 241 (2018) Ruth Arlow, Scott v. Stevenson & Reid Ltd: Northern Ireland Fair Employment Tribunal, 20 ECCLESIASTICAL L. J. 245 (2018) Giorgia Baldi, Re-conceptualizing Equality in the Work Place: A Reading of the Latest CJEU’s Opinions over the Practice of Veiling, 7 OXFORD J. L. & RELIG. 296 (2018) Luke Beck, The Role of Religion in the Law of Royal Succession in Canada and -

Friends Acquisitions 1964-2018

Acquired with the Aid of the Friends Manuscripts 1964: Letter from John Dury (1596-1660) to the Evangelical Assembly at Frankfurt-am- Main, 6 August 1633. The letter proposes a general assembly of the evangelical churches. 1966: Two letters from Thomas Arundel, Archbishop of Canterbury, to Nicholas of Lucca, 1413. Letter from Robert Hallum, Bishop of Salisbury concerning Nicholas of Lucca, n.d. 1966: Narrative by Leonardo Frescobaldi of a pilgrimage to the Holy Land in 1384. 1966: Survey of church goods in 33 parishes in the hundreds of Blofield and Walsham, Norfolk, 1549. 1966: Report of a debate in the House of Commons, 27 February 1593. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Petition to the Ecclesiastical Commissioners by Miles Coverdale and others, 1565. From the Fairhurst Papers. 1967: Correspondence and papers of Christopher Wordsworth (1807-1885), Bishop of Lincoln. 1968: Letter from John Whitgift, Archbishop of Canterbury, to John Boys, 1599. 1968: Correspondence and papers of William Howley (1766-1848), Archbishop of Canterbury. 1969: Papers concerning the divorce of Henry VIII and Catherine of Aragon. 1970: Papers of Richard Bertie, Marian exile in Wesel, 1555-56. 1970: Notebook of the Nonjuror John Leake, 1700-35. Including testimony concerning the birth of the Old Pretender. 1971: Papers of Laurence Chaderton (1536?-1640), puritan divine. 1971: Heinrich Bullinger, History of the Reformation. Sixteenth century copy. 1971: Letter from John Davenant, Bishop of Salisbury, to a minister of his diocese [1640]. 1971: Letter from John Dury to Mr. Ball, Preacher of the Gospel, 1639. 1972: ‘The examination of Valentine Symmes and Arthur Tamlin, stationers, … the Xth of December 1589’. -

The Origins of Historical Jurisprudence: Coke, Selden, Hale

Articles The Origins of Historical Jurisprudence: Coke, Selden, Hale Harold J. Berman CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ............................................. 1652 I. T HISTORICAL BACKGROUND OF ENGLISH LEGAL PHILOSOPHY, TWELFTH TO SEVENTEENTH CENTURIES ......................... 1656 A. Scholastic Jurisprudenceand Its Sixteenth-Century Rivals ......... 1656 B. Richard Hooker's "Comprehensive" Legal Philosophy ........... 1664 C. The Legal Theory of Absolute Monarchy: James I and Bodin ...... 1667 II. SIR EDWARD COKE: HIS MAJESTY'S LOYAL OPPONENT .............. 1673 A. Coke's Acceptance of James' Premises and the Sources of His Opposition to James' Conclusions ...................... 1673 B. Coke's Philosophy of English Law ......................... 1678 C. Coke's Historicism .................................... 1687 D. Coke's Concept of the English Common Law as Artificial Reason .... 1689 III. JOHN SELDEN'S LEGAL PHILOSOPHY .......................... 1694 t Robert NV.Woodruff Professor of Law, Emory Law School; James Barr Ames Professor of Law, Emeritus, Harvard Law School. The valuable collaboration of Charles J. Reid, Jr., Research Associate in Law and History, Emory Law School, is gratefully acknowledged. 1651 1652 The Yale Law Journal [Vol. 103: 1651 A. Coke to Selden to Hale ................................. 1694 B. Selden ' Historicity Versus Coke's Historicism ................. 1695 C. The Consensual Characterof Moral Obligations ............... 1698 D. The Origins of Positive Law in Customary Law ................ 1699 E. Magna Cartaand -

In Accordance with Usage: the Authority of Custom, the Stamp Act Debate, and the Coming of the American Revolution

Fordham Law Review Volume 45 Issue 2 Article 2 1976 In Accordance With Usage: The Authority of Custom, the Stamp Act Debate, and the Coming of the American Revolution John Phillip Reid Follow this and additional works at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation John Phillip Reid, In Accordance With Usage: The Authority of Custom, the Stamp Act Debate, and the Coming of the American Revolution , 45 Fordham L. Rev. 335 (1976). Available at: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol45/iss2/2 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. It has been accepted for inclusion in Fordham Law Review by an authorized editor of FLASH: The Fordham Law Archive of Scholarship and History. For more information, please contact [email protected]. In Accordance With Usage: The Authority of Custom, the Stamp Act Debate, and the Coming of the American Revolution Cover Page Footnote Professor, New York University Law School. B.S.S., 1952, Georgetown; LL.B., 1955, Harvard; LL.M., 1960, J.S.D., 1962, New York University. This article is available in Fordham Law Review: https://ir.lawnet.fordham.edu/flr/vol45/iss2/2 IN ACCORDANCE WITH USAGE: THE AUTHORITY OF CUSTOM, THE STAMP ACT DEBATE, AND THE COMING OF THE AMERICAN REVOLUTION JOHN PHILLIP REID* I. INTRODUCTION A s we mark the bicentennial of the American Revolution, it is time for lawyers to defend their own and demand their due. If jingoism in the writing of legal history is now under attack,' surely professional pride remains in fashion. -

The Ideology of Jury Law-Finding in the Interregnum

Conscience and the True Law: 5 The Ideology of Jury Law-Finding in the Interregnum The government that tried and condemned Charles I in January, 1649, found later the same year that it was unable to have its way with John Lilburne. As leader of the Levellers, the most imposing of the groups that clashed with the Cromwellian regime, Lilburne appealed to his jurors, in a celebrated phrase, "as judges of law as well as fact. " 1 When the jury acquitted him of treason, this claim to a "jury right"-a right of the jury to decide the law-brought the criminal trial jury for the first time into the forefront of English constitutional and political debate.2 The emergence of a theory of the jury's right to decide the law was not in any simple way a reaction to the transformation of criminal process in early modern England. On the one hand, much of what the radical reformers attacked predated the Tudor period; on the other, much of their program was inspired by the political crisis that accompanied the struggle against the Stuart monarchy .3 Nevertheless, the Leveller attack on the judiciary in criminal cases was a response to the power and behavior of the bench, and that power and behavior were largely owing to new forms of criminal procedure. 1. See below, text at nn. 67-77. On the Levellers see e.g. H. N. Brailsford, The Levellers and the English Revolution (London, 1961); Joseph Frank, The Levellers (Cambridge, Mass., 1955); G. E. Aylmer, ed., The Levellers in the English Revolution (London, 1975), pp. -

Historical Development of the Offence of Rape

HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE OFFENCE OF RAPE Bruce A. MacFarlane, Q.C. Deputy Minister of Justice Deputy Attorney General for the Province of Manitoba [Originally published by the Canadian Bar Association in a book commemorating the 100th anniversary of Canada’s criminal code, titled: “100 years of the criminal code in Canada; essays commemorating the centenary of the Canadian criminal code”, edited by Wood and Peck (1993)] HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE OFFENCE OF RAPE PAGE Introduction 1 Ancient Law 2 Medieval Saxon Laws 5 Thirteenth Century Legislation: The Statutes of Westminster 10 The Interlude 14 Rape Prosecutions in Eighteenth and Nineteenth Century England 17 (a) The Element of Force 18 (b) The Pregnant Complainant 30 (c) The Marital Rape Exemption 33 (d) Proof of Emission of Semen 41 (e) The Moral Character of the Complainant 48 (i) Birth of a Myth 50 (ii) The Legal Context 52 (a) Where the Complainant Had Previous Sexual Relations With the Accused 54 (b) Where The Complainant Had Sexual- Relations With Other Men 55 (c) Where the Complainant is a Prostitute 62 Development of the Law in Canada 67 Concluding Observations 76 ii HISTORICAL DEVELOPMENT OF THE OFFENCE OF RAPE Introduction Sexual assault is not like any other crime. Almost all perpetrators are male. Unlike other violent crimes, most incidents go unreported despite evidence suggesting that the rate of sexual assault is on the increase. While many forms of sexual activity are not in themselves illegal, the circumstances prevailing at the time -- such as an absence of consent or the youthfulness of a participant -- can make the activity illegal and expose one of the participants to a lengthy term of imprisonment.