The Suspension Clause: English Text, Imperial Contexts, and American Implications

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

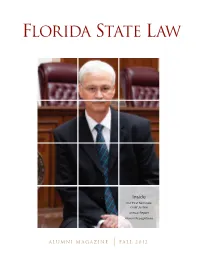

Fall 2012 Florida State Law Magazine

FLORIDA STATE LAW Inside Our First Seminole Chief Justice Annual Report Alumni Recognitions ALUMNI MAGAZINE FALL 2012 Message from the Dean Jobs, Alumni, Students and Admissions Players in the Jobs Market Admissions and Rankings This summer, the Wall Street The national press has highlighted the related phenomena Journal reported that we are the of the tight legal job market and rising student indebtedness. nation’s 25th best law school when it More prospective applicants are asking if a law degree is worth comes to placing our new graduates the cost, and law school applications are down significantly. in jobs that require law degrees. Just Ours have fallen by approximately 30% over the past two years. this month, Law School Transparency Moreover, our “yield” rate has gone down, meaning that fewer ranked us the nation’s 26th best law students are accepting our offers of admission. Our research school in terms of overall placement makes clear: prime competitor schools can offer far more score, and Florida’s best. Our web generous scholarship packages. To attract the top students, page includes more detailed information on our placement we must limit our enrollment and increase scholarship awards. outcomes. In short, we rank very high nationally in terms We are working with our university administration to limit of the number of students successfully placed. Although our our enrollment, which of course has financial implications average starting salary of $58,650 is less than those at the na- both for the law school and for the central university. It is tion’s most elite private law schools, so is our average student also imperative to increase our endowment in a way that will indebtedness, which is $73,113. -

The Political Effects of the Addition of Judgeships to the United States Supreme Court Following Electoral Realignments

A Compliant Court: The Political Effects of the Addition of Judgeships to the United States Supreme Court Following Electoral Realignments Lauren Paige Joyce Judson Thesis submitted to the faculty of the Virginia Polytechnic Institute and State University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of: Master of Arts In Political Science Jason P. Kelly, Chair Wayne D. Moore Karen M. Hult August 7, 2014 Blacksburg, Virginia Keywords: Judicial Politics, Electoral Realignment, Alteration to the Supreme Court Copyright 2014, Lauren J. Judson A Compliant Court: The Political Effects of the Addition of Judgeships to the United States Supreme Court Following Electoral Realignments Lauren J. Judson ABSTRACT During periods of turmoil when ideological preferences between the federal branches of government fail to align, the relationship between the three quickly turns tumultuous. Electoral realignments especially have the potential to increase tension between the branches. When a new party replaces the “old order” in both the legislature and the executive branches, the possibility for conflict emerges with the Court. Justices who make decisions based on old regime preferences of the party that had appointed them to the bench will likely clash with the new ideological preferences of the incoming party. In these circumstances, the president or Congress may seek to weaken the influence of the Court through court-curbing methods. One example Congress may utilize is changing the actual size of the Supreme The size of the Supreme Court has increased four times in United States history, and three out of the four alterations happened after an electoral realignment. Through analysis of Supreme Court cases, this thesis seeks to determine if, after an electoral realignment, holdings of the Court on issues of policy were more congruent with the new party in power after the change in composition as well to examine any change in individual vote tallies of the justices driven by the voting behavior of the newly appointed justice(s). -

Reform of the Elected Judiciary in Boss Tweed’S New York

File: 3 Lerner - Corrected from Soft Proofs.doc Created on: 10/1/2007 11:25:00 PM Last Printed: 10/7/2007 6:34:00 PM 2007] 109 FROM POPULAR CONTROL TO INDEPENDENCE: REFORM OF THE ELECTED JUDICIARY IN BOSS TWEED’S NEW YORK Renée Lettow Lerner* INTRODUCTION.......................................................................................... 111 I. THE CONSTITUTION OF 1846: POPULAR CONTROL...................... 114 II. “THE THREAT OF HOPELESS BARBARISM”: PROBLEMS WITH THE NEW YORK JUDICIARY AND LEGAL SYSTEM AFTER THE CIVIL WAR .................................................. 116 A. Judicial Elections............................................................ 118 B. Abuse of Injunctive Powers............................................. 122 C. Patronage Problems: Referees and Receivers................ 123 D. Abuse of Criminal Justice ............................................... 126 III. THE CONSTITUTIONAL CONVENTION OF 1867-68: JUDICIAL INDEPENDENCE............................................................. 130 A. Participation of the Bar at the Convention..................... 131 B. Natural Law Theories: The Law as an Apolitical Science ................................... 133 C. Backlash Against the Populist Constitution of 1846....... 134 D. Desire to Lengthen Judicial Tenure................................ 138 E. Ratification of the Judiciary Article................................ 143 IV. THE BAR’S REFORM EFFORTS AFTER THE CONVENTION ............ 144 A. Railroad Scandals and the Times’ Crusade.................... 144 B. Founding -

The Great Writ: Article I Habeas Corpus

The Great Writ Article I, Section 9, Clause 2: Habeas Corpus RECOMMENDED GRADE/ABILITY LEVEL: 11th-12th Grade RECOMMENDED LESSON LENGTH: One 50 minute class period ESSENTIAL QUESTION: When does a negative right become a right and, in the case of Habeas Corpus, to whom and in what cases does this right extend? OVERVIEW: In addition to the rights protected by the Bill of Rights, there are also a great deal of rights inherent to the Constitution itself, including the right to Habeas Corpus relief, created via a negative right. In this lesson, students will explore the history and purpose of the Habeas Corpus clause in the Constitution. In consideration of past and present caselaw concerning the application of Habeas Corpus (emphasizing issues of national security and separation of powers), students are tasked with the job of considering the question: When is a writ a right? To whom and in what cases can it extend? MATERIALS: 1. Article: You Should Have the Body: 5. Document: United States Circuit Court of Understanding Habeas Corpus by James Appeals, Second Circuit Decision: Bradley v. Landman (Appendix A) Watkins (Appendix D) [Middle challenge text] 2. Worksheet: 5 Ws of the Writ of Habeas 6. Document: Ex. Parte Merryman (Appendix Corpus (Appendix B) E) [Challenge text] 3. Prezi: The Great Writ: Habeas Corpus Prezi 7. Article: Constitution Check: Is the (found at: http://prezi.com/atlq7huw-adq/? president’s power to detain terrorism utm_campaign=share&utm_medium=copy) suspects about to lapse? by Lyle Denniston (Appendix F) 4. Document: Supreme Court Decision of 8. Protocol: Decoding a Court Opinion Boumediene v. -

16-1423 Ortiz V. United States (06/22/2018)

Summary 6/25/2018 1:41:01 PM Differences exist between documents. New Document: Old Document: 16-1423_new 16-1423 71 pages (394 KB) 71 pages (394 KB) 6/25/2018 1:40:53 PM 6/25/2018 1:40:53 PM Used to display results. Get started: first change is on page 43. No pages were deleted How to read this report Highlight indicates a change. Deleted indicates deleted content. indicates pages were changed. indicates pages were moved. file://NoURLProvided[6/25/2018 1:41:22 PM] (Slip Opinion) OCTOBER TERM, 2017 1 Syllabus NOTE: Where it is feasible, a syllabus (headnote) will be released, as is being done in connection with this case, at the time the opinion is issued. The syllabus constitutes no part of the opinion of the Court but has been prepared by the Reporter of Decisions for the convenience of the reader. See United States v. Detroit Timber & Lumber Co., 200 U. S. 321, 337. SUPREME COURT OF THE UNITED STATES Syllabus ORTIZ v. UNITED STATES CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ARMED FORCES No. 16–1423. Argued January 16, 2018—Decided June 22, 2018 Congress has long provided for specialized military courts to adjudicate charges against service members. Today, courts-martial hear cases involving crimes unconnected with military service. They are also subject to several tiers of appellate review, and thus are part of an in- tegrated “court-martial system” that resembles civilian structures of justice. That system begins with the court-martial itself, a tribunal that determines guilt or innocence and levies punishment, up to life- time imprisonment or execution. -

Volume II: Rights and Liberties Howard Gillman, Mark A. Graber

AMERICAN CONSTITUTIONALISM Volume II: Rights and Liberties Howard Gillman, Mark A. Graber, and Keith E. Whittington INDEX OF MATERIALS ARCHIVE 1. Introduction 2. The Colonial Era: Before 1776 I. Introduction II. Foundations A. Sources i. The Massachusetts Body of Liberties B. Principles i. Winthrop, “Little Speech on Liberty” ii. Locke, “The Second Treatise of Civil Government” iii. The Putney Debates iv. Blackstone, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” v. Judicial Review 1. Bonham’s Case 2. Blackstone, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” C. Scope i. Introduction III. Individual Rights A. Property B. Religion i. Establishment 1. John Witherspoon, The Dominion of Providence over the Passions of Man ii. Free Exercise 1. Ward, The Simple Cobler of Aggawam in America 2. Penn, “The Great Case of Liberty of Conscience” C. Guns i. Guns Introduction D. Personal Freedom and Public Morality i. Personal Freedom and Public Morality Introduction ii. Blackstone, “Commentaries on the Laws of England” IV. Democratic Rights A. Free Speech B. Voting i. Voting Introduction C. Citizenship i. Calvin’s Case V. Equality A. Equality under Law i. Equality under Law Introduction B. Race C. Gender GGW 9/5/2019 D. Native Americans VI. Criminal Justice A. Due Process and Habeas Corpus i. Due Process Introduction B. Search and Seizure i. Wilkes v. Wood ii. Otis, “Against ‘Writs of Assistance’” C. Interrogations i. Interrogations Introduction D. Juries and Lawyers E. Punishments i. Punishments Introduction 3. The Founding Era: 1776–1791 I. Introduction II. Foundations A. Sources i. Constitutions and Amendments 1. The Ratification Debates over the National Bill of Rights a. -

DATES of TRIALS Until October 1775, and Again from December 1816

DATES OF TRIALS Until October 1775, and again from December 1816, the printed Proceedings provide both the start and the end dates of each sessions. Until the 1750s, both the Gentleman’s and (especially) the London Magazine scrupulously noted the end dates of sessions, dates of subsequent Recorder’s Reports, and days of execution. From December 1775 to October 1816, I have derived the end dates of each sessions from newspaper accounts of the trials. Trials at the Old Bailey usually began on a Wednesday. And, of course, no trials were held on Sundays. ***** NAMES & ALIASES I have silently corrected obvious misspellings in the Proceedings (as will be apparent to users who hyper-link through to the trial account at the OBPO), particularly where those misspellings are confirmed in supporting documents. I have also regularized spellings where there may be inconsistencies at different appearances points in the OBPO. In instances where I have made a more radical change in the convict’s name, I have provided a documentary reference to justify the more marked discrepancy between the name used here and that which appears in the Proceedings. ***** AGE The printed Proceedings almost invariably provide the age of each Old Bailey convict from December 1790 onwards. From 1791 onwards, the Home Office’s “Criminal Registers” for London and Middlesex (HO 26) do so as well. However, no volumes in this series exist for 1799 and 1800, and those for 1828-33 inclusive (HO 26/35-39) omit the ages of the convicts. I have not comprehensively compared the ages reported in HO 26 with those given in the Proceedings, and it is not impossible that there are discrepancies between the two. -

The Uncrowned Lion: Rank, Status, and Identity of The

Robert Kurelić THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI MA Thesis in Medieval Studies Central European University Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ Chair, Examination Committee ____________________________________________ Thesis Supervisor ____________________________________________ Examiner Budapest May 2005 THE UNCROWNED LION: RANK, STATUS, AND IDENTITY OF THE LAST CILLI by Robert Kurelić (Croatia) Thesis submitted to the Department of Medieval Studies, Central European University, Budapest, in partial fulfillment of the requirements of the Master of Arts degree in Medieval Studies Accepted in conformance with the standards of the CEU ____________________________________________ External Examiner Budapest May 2005 I, the undersigned, Robert Kurelić, candidate for the MA degree in Medieval Studies declare herewith that the present thesis is exclusively my own work, based on my research and only such external information as properly credited in notes and bibliography. I declare that no unidentified and illegitimate use was made of the work of others, and no part of the thesis infringes on any person’s or institution’s copyright. I also declare that no part of the thesis has been submitted in this form to any other institution of higher education for an academic degree. Budapest, 27 May 2005 __________________________ Signature TABLE OF CONTENTS INTRODUCTION ____________________________________________________1 ...heind graffen von Cilli und nyemermer... _______________________________ 1 ...dieser Hunadt Janusch aus dem landt Walachey pürtig und eines geringen rittermessigen geschlechts was.. -

Just Because John Marshall Said It, Doesn't Make It So: Ex Parte

Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship 2000 Just Because John Marshall Said it, Doesn't Make it So: Ex Parte Bollman and the Illusory Prohibition on the Federal Writ of Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners in the Judiciary Act of 1789 Eric M. Freedman Maurice A. Deane School of Law at Hofstra University Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship Recommended Citation Eric M. Freedman, Just Because John Marshall Said it, Doesn't Make it So: Ex Parte Bollman and the Illusory Prohibition on the Federal Writ of Habeas Corpus for State Prisoners in the Judiciary Act of 1789, 51 Ala. L. Rev. 531 (2000) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.hofstra.edu/faculty_scholarship/53 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. It has been accepted for inclusion in Hofstra Law Faculty Scholarship by an authorized administrator of Scholarly Commons at Hofstra Law. For more information, please contact [email protected]. MILESTONES IN HABEAS CORPUS: PART I JUST BECAUSE JOHN MARSHALL SAID IT, DOESN'T MAKE IT So: Ex PARTE BoLLMAN AND THE ILLUSORY PROHIBITION ON THE FEDERAL WRIT OF HABEAS CORPUS FOR STATE PRISONERS IN THE JUDIcIARY ACT OF 1789 Eric M. Freedman* * Professor of Law, Hofstra University School of Law ([email protected]). BA 1975, Yale University;, MA 1977, Victoria University of Wellington (New Zea- land); J.D. 1979, Yale University. This work is copyrighted by the author, who retains all rights thereto. -

G:\OSG\Desktop

No. 08-267 In the Supreme Court of the United States UNITED STATES OF AMERICA, PETITIONER v. JACOB DENEDO ON PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI TO THE UNITED STATES COURT OF APPEALS FOR THE ARMED FORCES PETITION FOR A WRIT OF CERTIORARI GREGORY G. GARRE Acting Solicitor General LOUIS J. PULEO Counsel of Record Col., USMC MATTHEW W. FRIEDRICH Director Acting Assistant Attorney BRIAN K. KELLER General Deputy Director MICHAEL R. DREEBEN Deputy Solicitor General TIMOTHY H. DELGADO Lt., JAGC, USN ERIC D. MILLER Navy-Marine Corps Assistant to the Solicitor Appellate Government General Division JOHN F. DE PUE Department of the Navy Attorney Washington, D.C. 20374 Department of Justice Washington, D.C. 20530-0001 (202) 514-2217 QUESTION PRESENTED Whether an Article I military appellate court has ju- risdiction to entertain a petition for a writ of error co- ram nobis filed by a former service member to review a court-martial conviction that has become final under the Uniform Code of Military Justice, 10 U.S.C. 801 et seq. (I) TABLE OF CONTENTS Page Opinions below........................................ 1 Jurisdiction........................................... 1 Statutes involved...................................... 2 Statement............................................ 2 Reasons for granting the petition........................ 8 A. Collateral review of a final court-martial judgment is not “in aid of” the jurisdiction of a military appellate court.................................. 10 B. Coram nobis review is neither necessary nor appropriate in light of the alternative remedies available to former members of the armed forces.... 17 C. The question presented is important and warrants this Court’s review .............................. 21 Conclusion .......................................... 25 Appendix A — Court of appeals opinion (Mar. -

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II a Master's Thesis Presented to College of Arts & Sciences Departmen

COMIC BOOKS AS AMERICAN PROPAGANDA DURING WORLD WAR II A Master’s Thesis Presented To College of Arts & Sciences Department of Communications and Humanities _______________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Master of Science Degree _______________________________ SUNY Polytechnic Institute By David Dellecese May 2018 © 2018 David Dellecese Approval Page SUNY Polytechnic Institute DEPARTMENT OF COMMUNICATIONS AND HUMANITIES INFORMATION DESIGN AND TECHNOLOGY MS PROGRAM Approved and recommended for acceptance as a thesis in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Science in Information Design + Technology. _________________________ DATE ________________________________________ Kathryn Stam Thesis Advisor ________________________________________ Ryan Lizardi Second Reader ________________________________________ Russell Kahn Instructor 1 ABSTRACT American comic books were a relatively, but quite popular form of media during the years of World War II. Amid a limited media landscape that otherwise consisted of radio, film, newspaper, and magazines, comics served as a useful tool in engaging readers of all ages to get behind the war effort. The aims of this research was to examine a sampling of messages put forth by comic book publishers before and after American involvement in World War II in the form of fictional comic book stories. In this research, it is found that comic book storytelling/messaging reflected a theme of American isolation prior to U.S. involvement in the war, but changed its tone to become a strong proponent for American involvement post-the bombing of Pearl Harbor. This came in numerous forms, from vilification of America’s enemies in the stories of super heroics, the use of scrap, rubber, paper, or bond drives back on the homefront to provide resources on the frontlines, to a general sense of patriotism. -

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform

English Radicalism and the Struggle for Reform The Library of Sir Geoffrey Bindman, QC. Part I. BERNARD QUARITCH LTD MMXX BERNARD QUARITCH LTD 36 Bedford Row, London, WC1R 4JH tel.: +44 (0)20 7297 4888 fax: +44 (0)20 7297 4866 email: [email protected] / [email protected] web: www.quaritch.com Bankers: Barclays Bank PLC 1 Churchill Place London E14 5HP Sort code: 20-65-90 Account number: 10511722 Swift code: BUKBGB22 Sterling account: IBAN: GB71 BUKB 2065 9010 5117 22 Euro account: IBAN: GB03 BUKB 2065 9045 4470 11 U.S. Dollar account: IBAN: GB19 BUKB 2065 9063 9924 44 VAT number: GB 322 4543 31 Front cover: from item 106 (Gillray) Rear cover: from item 281 (Peterloo Massacre) Opposite: from item 276 (‘Martial’) List 2020/1 Introduction My father qualified in medicine at Durham University in 1926 and practised in Gateshead on Tyne for the next 43 years – excluding 6 years absence on war service from 1939 to 1945. From his student days he had been an avid book collector. He formed relationships with antiquarian booksellers throughout the north of England. His interests were eclectic but focused on English literature of the 17th and 18th centuries. Several of my father’s books have survived in the present collection. During childhood I paid little attention to his books but in later years I too became a collector. During the war I was evacuated to the Lake District and my school in Keswick incorporated Greta Hall, where Coleridge lived with Robert Southey and his family. So from an early age the Lake Poets were a significant part of my life and a focus of my book collecting.