West of England Learning and Skills Research Nextwork

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Strode College

REPORT FROM THE INSPECTORATE Strode College February 1994 THE FURTHER EDUCATION FUNDING COUNCIL THE FURTHER EDUCATION FUNDING COUNCIL The Further Education Funding Council (FEFC) has a statutory duty to ensure that there are satisfactory arrangements to assess the quality of provision in the further education sector. It discharges the duty in part through its inspectorate, which reports on each college in the sector every four years. The Council’s inspectorate also assesses and reports on a national basis on specific curriculum areas and advises the Council’s quality assessment committee. College inspections involve both full-time inspectors and registered part- time inspectors who have specialist knowledge and experience in the areas they inspect. Inspection teams normally include at least one member from outside the world of education and a nominated member of staff from the college being inspected. GRADE DESCRIPTORS The procedures for assessing quality are described in Council Circular 93/28. In the course of inspecting colleges, inspectors assess the strengths and weaknesses of each aspect of provision they inspect. Assessments are set out in their reports. They also summarise their judgements on the balance between strengths and weaknesses using a five-point scale. Each grade on the scale has the following descriptor: • grade 1 – provision which has many strengths and very few weaknesses • grade 2 – provision in which the strengths clearly outweigh the weaknesses • grade 3 – provision with a balance of strengths and weaknesses • -

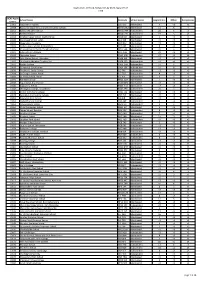

FOI 114/11 Crimes in Schools September 2010 – February 2011

FOI 114/11 Crimes in Schools September 2010 – February 2011 Incident Premisies Name Town / City Current Offence Group Count Abbeywood Community School Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 4 Alexandra Park Beechen Cliff School Bath Criminal Damage 1 Alexandra Park Beechen Cliff School Bath Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 4 Alexandra Park Beechen Cliff School Bath Violence Against The Person 1 Allen School House Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 0 Archbishop Cranmer Community C Of E School Taunton Burglary 1 Ashcombe Cp School Weston-Super-Mare Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 2 Ashcombe Primary School Weston-Super-Mare Violence Against The Person 0 Ashcott Primary School Bridgwater Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 0 Ashill Primary School Ilminster Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 1 Ashley Down Infant School Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 2 Ashton Park School Bristol Other Offences 1 Ashton Park School Bristol Sexual Offences 1 Ashton Park School Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 1 Avon Primary School Bristol Burglary 2 Backwell School Bristol Burglary 3 Backwell School Bristol Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 1 Backwell School Bristol Violence Against The Person 1 Badminton School Bristol Violence Against The Person 0 Banwell Primary School Banwell Theft And Handling Stolen Goods 1 Bartletts Elm School Langport Criminal Damage 0 Barton Hill County Infant School & Nursery Bristol Burglary 1 Barton Hill Primary School Bristol Violence Against The Person 0 Barwick Stoford Pre School Yeovil Fraud Forgery 1 Batheaston Primary -

Art & Design End of Year Catalogue 2020

End of year show Art & Design Student Show Catalogue June 2020 Cover photo credit Photographer: Catherine Hyde Fashon designer: Ellen Kinder Katy Quinn Principal, Strode College Welcome to Strode College’s End of Year Show 2020 Strode has held an end of year Art Show for several decades and the staff and students were determined to not let Covid-19 stand in the way of this well- established tradition. So the 2020 End of Year Show marks another innovative and creative approach through an E-book, building on the more traditional, historical venues such as Crispin Hall and Moorlands Factory. Typically, I’d be welcoming you in person to our End of Year Show, an annual event that is pivotal in the Art and Design calendar. But this year I am welcoming you virtually and am delighted that we can still showcase the amazing artwork that is tes- tament to the efforts and skills of students and staff from Creative Arts and Design. Quite clearly, this year we needed to reconsider how to celebrate and share the work undertaken in the visual arts; hopefully you will enjoy the work that is presented in this book and even recognise some of our artists and their work. It is pleasing to see that range of disciplines have been explored and are well represented by the students in Art and Design. I hope you enjoy the references in props and set design to ‘The Little Shop of Horrors’ which was a joint venture between our visual and performing arts team. We now need to find a suitable space in the college to showcase “Audrey!” Other positive collaborations include the live shoe design brief undertaken with Clarks design and innovation team, which provides our students with a wonderful insight into corporate design. -

2010 Somerset County Aa Championships

Yeovil Olympiads Athletic Club Hy-Tek's MEET MANAGER 11:10 AM 09/05/2010 Page 1 2010 SOMERSET COUNTY AA CHAMPIONSHIPS - 24/04/2010 to 08/05/2010 Results Girls 11-12 100 Meter Sprint HEATS ===================================================================== CBP: R 13.70 1988 J.Brown, YOAC Name Age Team Prelims Wind ===================================================================== Preliminaries 1 20 Sheves, Harriet 12 BRUTON SCHOOL FO 14.55Q 3.7 1 339 Bryant, Alicia 12 TAUNTON AC 14.55Q 3.7 3 194 Nanton, Hannah 12 MILLPREP 14.67q 3.7 3 338 Brown, Maisie 12 TAUNTON AC 14.67q 3.7 5 146 Allen, Eleanor 12 MENDIP AC 14.95q 3.7 6 306 Hoskins, Olivia 12 QUEENS COLLEGE,T 14.97q 3.7 7 345 Lincoln, Beth 12 TAUNTON AC 15.06q 3.7 8 407 Bell, Emily 12 WELLS CATHEDRAL 15.26q 3.7 9 153 Lavender, Claudia 12 MENDIP AC 15.36 3.7 10 154 Loosemore, Hannah 11 MENDIP AC 15.44 3.7 11 440 Azariah, Cara 11 YEOVIL AND WELLS AC 15.51 3.7 12 286 Conroy, Hannah 11 QUEENS COLLEGE J 15.63 3.7 13 329 Petrovic, Hannah 12 SEXEYS 15.86 3.7 14 276 Denham, Emma 11 PARK SCHOOL YEOVIL 16.00 3.7 15 185 Casterton, Poppy 12 MILLPREP 16.54 3.7 16 411 Manning, M 12 WELLS CATHEDRAL 17.04 3.7 Girls 11-12 100 Meter Sprint FINAL ============================================================================ CBP: R 13.70 1988 J.Brown, YOAC Name Age Team Finals Wind Points ============================================================================ Finals 1 20 Sheves, Harriet 12 BRUTON SCHOOL FO 14.10 1.4 2 338 Brown, Maisie 12 TAUNTON AC 14.30 1.4 3 306 Hoskins, Olivia 12 QUEENS COLLEGE,T -

Copy of NNDR Assessments Exceeding 30000 20 06 11

Company name Full Property Address inc postcode Current Rateable Value Eriks Uk Ltd Ber Ltd, Brassmill Lane, Bath, BA1 3JE 69000 Future Publishing Ltd 1st & 2nd Floors, 5-10, Westgate Buildings, Bath, BA1 1EB 163000 Nationwide Building Society Nationwide Building Society, 3-4, Bath Street, Bath, BA1 1SA 112000 The Eastern Eye Ltd 1st & 2nd Floors, 8a, Quiet Street, Bath, BA1 2JU 32500 Messers A Jones & Sons Ltd 19, Cheap Street, Bath, BA1 1NA 66000 Bath & N E Somerset Council 12, Charlotte Street, Bath, BA1 2NE 41250 Carr & Angier Levels 6 & Part 7, The Old Malthouse, Clarence Street, Bath, BA1 5NS 30500 Butcombe Brewery Ltd Old Crown (The), Kelston, Bath, BA1 9AQ 33000 Shaws (Cardiff) Ltd 19, Westgate Street, Bath, BA1 1EQ 50000 Lifestyle Pharmacy Ltd 14, New Bond Street, Bath, BA1 1BE 84000 Bath Rugby Ltd Club And Prems, Bath Rfc, Pulteney Mews, Bath, BA2 4DS 110000 West Of England Language Services Ltd International House Language S, 5, Trim Street, Bath, BA1 1HB 43250 O'Hara & Wood 29, Gay Street, Bath, BA1 2PD 33250 Wellsway (Bath) Ltd Wellsway B.M.W., Lower Bristol Road, Bath, BA2 3DR 131000 Bath & N E Somerset Council Lewis House, Manvers Street, Bath, BA1 1JH 252500 Abbey National Bldg Society Abbey National Bldg Society, 5a-6, Bath Street, Bath, BA1 1SA 84000 Paradise House Hotel, 86-88, Holloway, Bath, BA2 4PS 42000 12, Upper Borough Walls, Bath, BA1 1RH 35750 Moss Electrical Ltd 45-46 St James Parade, Lower Borough Walls, Bath, BA1 1UQ 49000 Claire Accessories Uk Ltd 23, Stall Street, Bath, BA1 1QF 100000 Thorntons Plc 1st Floor -

INSPECTION REPORT NORTON HILL SCHOOL Midsomer Norton

INSPECTION REPORT NORTON HILL SCHOOL Midsomer Norton, N E Somerset LEA area: Bath and N E Somerset Unique reference number: 109301 Headteacher: Mr P Beaven Reporting inspector: Mr John Rowley 18648 Dates of inspection: 31 March – 4 April 2003 Inspection number: 249844 Short inspection carried out under section 10 of the School Inspections Act 1996 © Crown copyright 2003 This report may be reproduced in whole or in part for non-commercial educational purposes, provided that all extracts quoted are reproduced verbatim without adaptation and on condition that the source and date thereof are stated. Further copies of this report are obtainable from the school. Under the School Inspections Act 1996, the school must provide a copy of this report and/or its summary free of charge to certain categories of people. A charge not exceeding the full cost of reproduction may be made for any other copies supplied. INFORMATION ABOUT THE SCHOOL Type of school: Comprehensive School category: Community Age range of pupils: 11-18 Gender of pupils: Mixed School address: Charlton Road Midsomer Norton Radstock Postcode: BA3 4AD Telephone number: 01761 412557 Fax number: 01761 410622 Appropriate authority: Governing Body Name of chair of governors: Mr Terry Fussell Date of previous inspection: April 1997 Norton Hill School - 4 INFORMATION ABOUT THE INSPECTION TEAM Subject responsibilities Aspect responsibilities Team members (sixth form) (sixth form) 18648 John Rowley Registered Psychology What sort of school is it? inspector The school’s results and achievements. How well are students taught? How good are the curricular and other opportunities? 11072 Shirley Elomari Lay inspector Students’ attitudes, values and persona development. -

Issue 1, Monday 1St June 2015

Issue 1, Monday 1st June 2015 BET NEWS A newsletter for all our colleagues and partners Welcome to our first edition Bath Education Trust (BET) is a schools and colleges and prepare them The articles in this first newsletter reflect partnership and collaboration of key for the opportunities, responsibilities and the work of all partners in the Trust. education providers and businesses in experiences of later life. We plan to produce two newsletters per Bath and North East Somerset. Further information about BET year and future editions will be designed Our aim is to improve the educational can be found on our website www. and produced by students from our experience of young people in our batheducationtrust.com schools and college. Three Ways School Three Ways School has worked and what fire personnel do to adapt the Award to enhance on a day to day basis. the development of lifeskills and Students, not only employability skills for their sixth enjoyed the day but, they form students. responded, listened intently The award has helped to develop and acted positively on general social skills and the information presented to students understanding that them by White watch in a the wider world will have a wide hugely encouraging way. variety of expectations. The class teacher, Kirsten Workshops, work experience Hafford said, ‘Our pupils and volunteering outside school had a fantastic time, white has hugely benefited students watch made quite an confidence and experience of impression on them! It was the working world. One student great that the activities were has worked in a party shop on a in Walcot St, Bath Party Shop and the all practical, and will be really helpful for independent living.’ weekly basis, developing interpersonal Roman Baths. -

Progress on Strategic Goals and Impact Report 2019

The Alcohol Education Trust Progress On Strategic Goals And Impact Report 2019 Progress on strategic goals and impact report 2019 - page 1 Progress on strategic goals and impact report 2019 - page 2 Introduction from Vicky McDonaugh, Chair of Trustees Thanks to the dedication of our staff, Trustees and volunteers, together with the energy of Helena, we have had 3 very successful 10th anniversary celebrations in 2019 and have reflected on our not inconsiderable achievements over the decade. It is now time to look forward to our next 10 years. In this report, you will see how the Alcohol Eduction Trust (AET) expects to deepen and expand its remit. Both in terms of geography, outreaches to more vulnerable young people and in the number of schools and settings using our highly evaluated materials. One of the main reasons I joined the AET was to try and reduce levels of drunkenness among young people, a key contributing factor to unwanted pregnancies and STDs. In its 2018 report, the BPAS (British Pregnancy Advisory Service) identifies low levels of alcohol consumption as one of the main reasons why teenage pregnancy rates have fallen by 55% in the last decade, to the lowest ever level. I have no doubt that the AET, in providing the only evidence based alcohol education programme used in schools, has contributed to this decline. In 2020 we move into a new office with a cafe attached, which will bring a regular income to the charity. 2020 will also see AET materials being used in an increasing number of schools as elements of PSHE, including alcohol education, become statutory. -

2014 Admissions Cycle

Applications, Offers & Acceptances by UCAS Apply Centre 2014 UCAS Apply School Name Postcode School Sector Applications Offers Acceptances Centre 10002 Ysgol David Hughes LL59 5SS Maintained 4 <3 <3 10008 Redborne Upper School and Community College MK45 2NU Maintained 11 5 4 10011 Bedford Modern School MK41 7NT Independent 20 5 3 10012 Bedford School MK40 2TU Independent 19 3 <3 10018 Stratton Upper School, Bedfordshire SG18 8JB Maintained 3 <3 <3 10020 Manshead School, Luton LU1 4BB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10022 Queensbury Academy LU6 3BU Maintained <3 <3 <3 10024 Cedars Upper School, Bedfordshire LU7 2AE Maintained 4 <3 <3 10026 St Marylebone Church of England School W1U 5BA Maintained 20 6 5 10027 Luton VI Form College LU2 7EW Maintained 21 <3 <3 10029 Abingdon School OX14 1DE Independent 27 13 13 10030 John Mason School, Abingdon OX14 1JB Maintained <3 <3 <3 10031 Our Lady's Abingdon Trustees Ltd OX14 3PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10032 Radley College OX14 2HR Independent 10 4 4 10033 St Helen & St Katharine OX14 1BE Independent 14 8 8 10036 The Marist Senior School SL5 7PS Independent <3 <3 <3 10038 St Georges School, Ascot SL5 7DZ Independent 4 <3 <3 10039 St Marys School, Ascot SL5 9JF Independent 6 3 3 10041 Ranelagh School RG12 9DA Maintained 7 <3 <3 10043 Ysgol Gyfun Bro Myrddin SA32 8DN Maintained <3 <3 <3 10044 Edgbarrow School RG45 7HZ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10045 Wellington College, Crowthorne RG45 7PU Independent 20 6 6 10046 Didcot Sixth Form College OX11 7AJ Maintained <3 <3 <3 10048 Faringdon Community College SN7 7LB Maintained -

237 Colleges in England.Pdf (PDF,196.15

This is a list of the formal names of the Corporations which operate as colleges in England, as at 3 February 2021 Some Corporations might be referred to colloquially under an abbreviated form of the below College Type Region LEA Abingdon and Witney College GFEC SE Oxfordshire Activate Learning GFEC SE Oxfordshire / Bracknell Forest / Surrey Ada, National College for Digital Skills GFEC GL Aquinas College SFC NW Stockport Askham Bryan College AHC YH York Barking and Dagenham College GFEC GL Barking and Dagenham Barnet and Southgate College GFEC GL Barnet / Enfield Barnsley College GFEC YH Barnsley Barton Peveril College SFC SE Hampshire Basingstoke College of Technology GFEC SE Hampshire Bath College GFEC SW Bath and North East Somerset Berkshire College of Agriculture AHC SE Windsor and Maidenhead Bexhill College SFC SE East Sussex Birmingham Metropolitan College GFEC WM Birmingham Bishop Auckland College GFEC NE Durham Bishop Burton College AHC YH East Riding of Yorkshire Blackburn College GFEC NW Blackburn with Darwen Blackpool and The Fylde College GFEC NW Blackpool Blackpool Sixth Form College SFC NW Blackpool Bolton College FE NW Bolton Bolton Sixth Form College SFC NW Bolton Boston College GFEC EM Lincolnshire Bournemouth & Poole College GFEC SW Poole Bradford College GFEC YH Bradford Bridgwater and Taunton College GFEC SW Somerset Brighton, Hove and Sussex Sixth Form College SFC SE Brighton and Hove Brockenhurst College GFEC SE Hampshire Brooklands College GFEC SE Surrey Buckinghamshire College Group GFEC SE Buckinghamshire Burnley College GFEC NW Lancashire Burton and South Derbyshire College GFEC WM Staffordshire Bury College GFEC NW Bury Calderdale College GFEC YH Calderdale Cambridge Regional College GFEC E Cambridgeshire Capel Manor College AHC GL Enfield Capital City College Group (CCCG) GFEC GL Westminster / Islington / Haringey Cardinal Newman College SFC NW Lancashire Carmel College SFC NW St. -

Norton Radstock College

Norton Radstock College REPORT FROM THE INSPECTORATE 1998-99 THE FURTHER EDUCATION FUNDING COUNCIL THE FURTHER EDUCATION FUNDING COUNCIL The Further Education Funding Council (FEFC) has a legal duty to make sure further education in England is properly assessed. The FEFC’s inspectorate inspects and reports on each college of further education according to a four-year cycle. It also inspects other further education provision funded by the FEFC. In fulfilling its work programme, the inspectorate assesses and reports nationally on the curriculum, disseminates good practice and advises the FEFC’s quality assessment committee. College inspections are carried out in accordance with the framework and guidelines described in Council Circulars 97/12, 97/13 and 97/22. Inspections seek to validate the data and judgements provided by colleges in self-assessment reports. They involve full-time inspectors and registered part-time inspectors who have knowledge of, and experience in, the work they inspect. A member of the Council’s audit service works with inspectors in assessing aspects of governance and management. All colleges are invited to nominate a senior member of their staff to participate in the inspection as a team member. Cheylesmore House Quinton Road Coventry CV1 2WT Telephone 01203 863000 Fax 01203 863100 Website http://www.fefc.ac.uk © FEFC 1999 You may photocopy this report and use extracts in promotional or other material provided quotes are accurate, and the findings are not misrepresented. Contents Paragraph Summary Context The college and its mission 1 The inspection 6 Curriculum areas Engineering 9 Business administration 16 Health and social care 23 Humanities 29 Cross-college provision Support for students 33 General resources 40 Quality assurance 47 Governance 57 Management 64 Conclusions 74 College statistics Norton Radstock College Grade Descriptors Student Achievements Inspectors assess the strengths and weaknesses Where data on student achievements appear in of each aspect of provision they inspect. -

Post 16 Options for Pupils in Transitions (Years 11-14

What happens if a young person with SEN stays at school post-16? If the pupil is staying at school, they will maintain their statement of special educational need until the end of the Post 16 Options for Pupils in academic year in which they reach the age of 19 or until they leave statutory education. Transitions (Years 11-14) Connexions West is commissioned by the Local Authority to Information for support young people and their parents/carers in looking at Parents and Carers the options throughout their time at school and beyond. What other educational options are available post-16? A young person’s statement will lapse when leaving school, and be replaced by an S139A assessment, which assesses educational need in a similar way to the Statement. The S139A is completed by a Personal Advisor from the Connexions Service, who will assess the best option for the young person, which can include apprenticeships with a work-based learning provider or supported employment. For pupils wishing to continue in education: Further Education College in the West of England area – the Connexions service will help identify the best College, course and additional support required for the young person. The LA believe that local education is best No offer of local FE College – an application for a place at a specialist residential college made through Connexions. This will then be considered by a LA panel. When do college applications have to be in? By the April prior to the young person is attending college, in line with the S139a assessment completed by Connexions and any Social Services input that may be required.