To Make Their Own Way in the World

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

How to Use This Guide

How to Use this Guide The New-York Historical Society, one of America’s pre-eminent cultural institutions, is dedicated to fostering research, presenting history and art exhibitions, and public programs that reveal the dynamism of history and its influence on the world of today. Founded in 1804, New-York Historical has a mission to explore the richly layered political, cultural and social history of New York City and State and the nation, and to serve as a national forum for the discussion of issues surrounding the making and meaning of history. Student Historians are high school interns at New-York Historical who explore our museum and library collection and conduct research using the resources available to them within a museum setting. Their project this academic year was to create a guide for fellow high school students preparing for U.S. History Exams, particularly the U.S. History & Government Regents Exam. Each Student Historian chose a piece from our collection that represents a historical event or theme often tested on the exam, collected and organized their research, and wrote about their piece within its historic context. The intent is that this catalog will provide a valuable supplemental review material for high school students preparing for U.S. History Exams. The following summative essays are all researched and written by the 2015-16 Student Historians, compiled in chronological order, and organized by unit. Each essay includes an image of the object or artwork from the N-YHS collection that serves as the foundation for the U.S. History content reviewed. Additional educational supplementary materials include a glossary of frequently used terms, review activities including a crossword puzzle as well as questions and answers taken from past U.S. -

Race and Membership in American History: the Eugenics Movement

Race and Membership in American History: The Eugenics Movement Facing History and Ourselves National Foundation, Inc. Brookline, Massachusetts Eugenicstextfinal.qxp 11/6/2006 10:05 AM Page 2 For permission to reproduce the following photographs, posters, and charts in this book, grateful acknowledgement is made to the following: Cover: “Mixed Types of Uncivilized Peoples” from Truman State University. (Image #1028 from Cold Spring Harbor Eugenics Archive, http://www.eugenics archive.org/eugenics/). Fitter Family Contest winners, Kansas State Fair, from American Philosophical Society (image #94 at http://www.amphilsoc.org/ library/guides/eugenics.htm). Ellis Island image from the Library of Congress. Petrus Camper’s illustration of “facial angles” from The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. Inside: p. 45: The Works of the Late Professor Camper by Thomas Cogan, M.D., London: Dilly, 1794. 51: “Observations on the Size of the Brain in Various Races and Families of Man” by Samuel Morton. Proceedings of the Academy of Natural Sciences, vol. 4, 1849. 74: The American Philosophical Society. 77: Heredity in Relation to Eugenics, Charles Davenport. New York: Henry Holt &Co., 1911. 99: Special Collections and Preservation Division, Chicago Public Library. 116: The Missouri Historical Society. 119: The Daughters of Edward Darley Boit, 1882; John Singer Sargent, American (1856-1925). Oil on canvas; 87 3/8 x 87 5/8 in. (221.9 x 222.6 cm.). Gift of Mary Louisa Boit, Julia Overing Boit, Jane Hubbard Boit, and Florence D. Boit in memory of their father, Edward Darley Boit, 19.124. -

“A Greater Compass of Voice”: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary Navigate Black Performance Kristin Moriah

Document generated on 10/01/2021 9:01 a.m. Theatre Research in Canada Recherches théâtrales au Canada “A Greater Compass of Voice”: Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary Navigate Black Performance Kristin Moriah Volume 41, Number 1, 2020 Article abstract The work of Elizabeth Taylor Greenfield and Mary Ann Shadd Cary URI: https://id.erudit.org/iderudit/1071754ar demonstrate how racial solidarity between Black Canadians and African DOI: https://doi.org/10.3138/tric.41.1.20 Americans was created through performance and surpassed national boundaries during the nineteenth century. Taylor Greenfield’s connection to See table of contents Mary Ann Shadd Cary, the prominent feminist abolitionist, and the first Black woman to publish a newspaper in North America, reveals the centrality of peripatetic Black performance, and Black feminism, to the formation of Black Publisher(s) Canada’s burgeoning community. Her reception in the Black press and her performance work shows how Taylor Greenfield’s performances knit together Graduate Centre for the Study of Drama, University of Toronto various ideas about race, gender, and nationhood of mid-nineteenth century Black North Americans. Although Taylor Greenfield has rarely been recognized ISSN for her role in discourses around race and citizenship in Canada during the mid-nineteenth century, she was an immensely influential figure for both 1196-1198 (print) abolitionists in the United States and Blacks in Canada. Taylor Greenfield’s 1913-9101 (digital) performance at an event for Mary Ann Shadd Cary’s benefit testifies to the longstanding porosity of the Canadian/ US border for nineteenth century Black Explore this journal North Americans and their politicized use of Black women’s voices. -

Copyright by Jacob Charles Maguire 2011

Copyright by Jacob Charles Maguire 2011 The Report Committee for Jacob Charles Maguire Certifies that this is the approved version of the following report: “Though It Blasts Their Eyes”: Slavery and Citizenship in New York City, 1790-1821 APPROVED BY SUPERVISING COMMITTEE: Supervisor: Shirley Thompson Jeffrey Meikle “Though It Blasts Their Eyes”: Slavery and Citizenship in New York City, 1790-1821 by Jacob Charles Maguire, B.A. Report Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Master of Arts The University of Texas at Austin May 2011 Dedication For my dad, who always taught me about citizenship Abstract “Thought It Blasts Their Eyes”: Slavery and Citizenship in New York City, 1790-1821 Jacob Charles Maguire, M.A. The University of Texas at Austin, 2011 Supervisor: Shirley Thompson Between 1790 and 1821, New York City underwent a dramatic transformation as slavery slowly died. Throughout the 1790s, a massive influx of runaways from the hinterland and black refugees from the Caribbean led to the rapid expansion of the city’s free black population. At the same time, white agitation for abolition reached a fever pitch. The legislature’s decision in 1799 to enact a program of gradual emancipation set off a wave of arranged manumissions that filled city streets with black bodies at all stages of transition from slavery to freedom. As blacks began to organize politically and develop a distinct social, economic and cultural life, they both conformed to and defied white expectations of republican citizenship. -

Diplomacy and the American Civil War: the Impact on Anglo- American Relations

James Madison University JMU Scholarly Commons Masters Theses, 2020-current The Graduate School 5-8-2020 Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo- American relations Johnathan Seitz Follow this and additional works at: https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029 Part of the Diplomatic History Commons, Public History Commons, and the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Seitz, Johnathan, "Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The impact on Anglo-American relations" (2020). Masters Theses, 2020-current. 56. https://commons.lib.jmu.edu/masters202029/56 This Thesis is brought to you for free and open access by the The Graduate School at JMU Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Masters Theses, 2020-current by an authorized administrator of JMU Scholarly Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Diplomacy and the American Civil War: The Impact on Anglo-American Relations Johnathan Bryant Seitz A thesis submitted to the Graduate Faculty of JAMES MADISON UNIVERSITY In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the degree of Master of Arts Department of History May 2020 FACULTY COMMITTEE: Committee Chair: Dr. Steven Guerrier Committee Members/ Readers: Dr. David Dillard Dr. John Butt Table of Contents List of Figures..................................................................................................................iii Abstract............................................................................................................................iv Introduction.......................................................................................................................1 -

Hyde Park Historical Record (Vol

' ' HYDE PARK ' ' HISTORICAL RECORD ^ ^ VOLUME IV : 1904 ^ ^ ISe HYDE PARK HISTORICAL SOCIETY j< * HYDE PARK, MASSACHUSETTS * * HYDE PARK HISTORICAL RECORD Volume IV— 1904 PUBLISHED BY THE HYDE PARK HISTORICAL SOCIETY HYDE PARK, MASS. PRESS OF . THE HYDE PARK GAZETTE . 1904 . OFFICERS FOR J904 President Charles G. Chick Recording Secretary Fred L. Johnson Corresponding Secretary and Librarian Henry B. Carrington, 19 Summer Street, Hyde Park, Mass. Treasurer Henry B. Humphrey Editor William A. Mowry, 17 Riverside Square, Hyde Park, Mass. Curators Amos H. Brainard Frank B. Rich George L. Richardson J. Roland Corthell. George L. Stocking Alfred F. Bridgman Charles F. Jenney Henry B, Carrington {ex ofido) CONTENTS OF VOLUME IV. THEODORE DWIGHT WELD 5-32 IVi'lliam Lloyd Garrison, "J-r., Charles G. Chick, Henry B. Carrington, Mrs. Albert B. Bradley, Mrs. Cordelia A. Pay- son, Wilbur H. Po'vers, Francis W. Darling; Edtvard S. Hathazvay. JOHN ELIOT AND THE INDIAN VILLAGE AT NATICK . 33-48 Erastus Worthington. GOING WEST IN 1820. George L. Richardson .... 49-67 EDITORIAL. William A. Mowry 68 JACK FROST (Poem). William A. Mo-vry 69 A HYDE PARK MEMORIAL, 18SS (with Ode) .... 70-75 Henry B- Carrington. HENRY A. RICH 76, 77 William y. Stuart, Robert Bleakie, Henry S. Bunton. DEDICATION OF CAMP MEIGS (1903) 78-91 Henry B. Carrington, Augustus S. Lovett, BetiJ McKendry. PROCEEDINGS OF THE SOCIETY SINCE 1892 . 92-100 Fred L. 'Johnso7i. John B. Bachelder. Henry B- Carrington, Geo. M. Harding, yohn y. E7ineking ..... 94, 95 Gov. F. T. Greenhalge. C. Fred Allen, John H. ONeil . 96 Annual Meeting, 1897. Charles G. -

Physiognomy in Ancient Science and Medicine

Physiognomy Mariska Leunissen The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Introduction Physiognomy(fromthelaterGreek physiognōmia ,whichisacontractionoftheclassicalform physiognōmonia )referstotheancientscienceofdeterminingsomeone’sinnatecharacteronthe basisoftheiroutward,andhenceobservable,bodilyfeatures.Forinstance,Socrates’famous snubnosewasuniversallyinterpretedbyancientphysiognomistsasaphysiognomicalsignof hisinnatelustfulness,whichheonlyovercamethroughphilosophicaltraining.Thediscipline initstechnicalformwithitsownspecializedpractitionersfirstsurfacesinGreeceinthefifth century BCE ,possiblythroughconnectionswiththeNearEast,wherebodilysignswere takenasindicatorsofsomeone’sfutureratherthanhischaracter.Theshifttocharacter perhapsarisesfromthewidespreadculturalpracticeintheancientGreekandRomanworld oftreatingsomeone’soutwardappearanceasindicativeforhispersonality,whichisalready visibleinHomer(eighthcentury BCE ).Inthe Iliad ,forinstance,adescriptionofThersites’ quarrelsomeandrepulsivecharacterisfollowedbyadescriptionofhisequallyuglybody(see Iliad 2.211–219),suggestingthatthiscorrespondencebetweenbodyandcharacterisno accident.ThersitesisthustheperfectfoilfortheGreekidealofthe kaloskagathos –theman whoisbothbeautifulandgood.Thesameholdsforthepracticeofattributingcharacter traitsassociatedwithaparticularanimalspeciestoapersonbasedonsimilaritiesintheir physique:itisfirstformalizedinphysiognomy,butwasalreadywidelyusedinanon- 1 technicalwayinancientliterature.Themostfamousexampleofthelatterisperhaps SemonidesofAmorgos’satireofwomen(fragment7 -

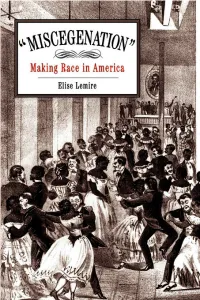

Miscegenation” This Page Intentionally Left Blank “Miscegenation” Making Race in America

“Miscegenation” This page intentionally left blank “Miscegenation” Making Race in America ELISE LEMIRE PENN UNIVERSITY OF PENNSYLVANIA PRESS Philadelphia Copyright © 2002 University of Pennsylvania Press All rights reserved Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper 10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 Published by University of Pennsylvania Press Philadelphia, Pennsylvania 19104-4011 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Lemire, Elise Virginia. “Miscegenation” : making race in America / Elise Lemire. p. cm. Includes bibliographical references (p. ) and index. ISBN 0-8122-2064-3 (alk. paper) 1. American literature—19th century—History and criticism. 2. Miscegenation in literature. 3. Literature and society—United States—History—19th century. 4. Jeff erson, Th omas, 1743–1826—In literature. 5. Racially mixed people in literature. 6. Race relations in literature. 7. Racism in literature. 8. Race in literature. I. Title. PS217.M57 L46 2002 810.9'355—dc21 2002018048 For Jim This page intentionally left blank Contents List of Illustrations ix Introduction: The Rhetorical Wedge Between Preference and Prejudice 1 1. Race and the Idea of Preference in the New Republic: The Port Folio Poems About Thomas Jefferson and Sally Hemings 11 2. The Rhetoric of Blood and Mixture: Cooper’s “Man Without a Cross” 35 3. The Barrier of Good Taste: Avoiding A Sojourn in the City of Amalgamation in the Wake of Abolitionism 53 4. Combating Abolitionism with the Species Argument: Race and Economic Anxieties in Poe’s Philadelphia 87 5. Making “Miscegenation”: Alcott’s Paul Frere and the Limits of Brotherhood After Emancipation 115 Epilogue: “Miscegenation” Today 145 Notes 149 Bibliography 179 Index 191 Acknowledgments 203 This page intentionally left blank Illustrations 1. -

The African Free School Page 1 of 7

The African Free School Page 1 of 7 Relevant Unit Objectives Module 1: African American Community and Culture This lesson addresses the following Essential Questions: . How did the existence of slavery shape African American communal life and cultural expression? . How is community defined? . How was the African American community defined? Objectives of the Lesson Aim How did the establishment of free schools for African Americans in 18th- and 19th-century New York help transform the lives and identities of its students? At the conclusion of this lesson, students will be able to: . Evaluate the significance of education and literacy to the larger African American community in New York City . Situate the development of schools for African American students within the larger development of public education in New York City . Assess how the education received at the African Free School helped create a class of important African American leaders . Evaluate the importance of education and literacy to democratic participation . Identify some of the literary contributions of James Weldon Johnson and Frances E.W. Harper Introduction Distribute Handout 1, the poem “Learning to Read” by Frances E. W. Harper, an abolitionist and poet born in Maryland in 1825. The poem describes the experience of a freedwoman who was taught to read during Reconstruction. Ask students to consider the following in terms of the poem: 1. Why did southern slaveholders try to prevent slaves from learning to read? 2. What were some of the strategies slaves used to try to learn to read? 3. Why was it so important to the slaves and freedmen to learn to read? What did literacy represent to them? 4. -

Using Facial Angle to Prove Evolution and the Human Race Hierarchy Jerry Bergman

Papers Using facial angle to prove evolution and the human race hierarchy Jerry Bergman A measurement technique called facial angle has a history of being used to rank the position of animals and humans on the evolutionary hierarchy. The technique was exploited for several decades in order to prove evolution and justify racism. Extensive research on the correlation of brain shapes with mental traits and also the falsification of the whole field of phrenology, an area to which the facial angle theory was strongly linked, caused the theory’s demise. he use of the facial angle, a method of measuring but also the difference between the human “races”.8 Science Tthe forehead-to-jaw relationship, has a long history historian John Haller concluded that the “facial angle was and was often used to make judgments of inferiority and the most extensively elaborated and artlessly abused criteria superiority of certain human races. University of Chicago for racial somatology.”2 zoology professor Ransom Dexter wrote that the “subject of Supporters of this theory cited as proof convincing, the facial angle has occupied the attention of philosophers but very distorted, drawings of an obvious black African or from earliest antiquity.”1 Aristotle used it to help determine Australian Aborigine as being the lowest type of human and a person’s intelligence and to rank humans from inferior a Caucasian as the highest racial type. The slanting African to superior.2 It was first used in modern times to compare forehead shown in the pictures indicates a smaller frontal human races by Petrus Camper (1722–1789), and it became cortex, such as is typical of an ape, demonstrating to naïve widely popular until disproved in the early 20th century.2 observers their inferiority. -

Kaltz Text Final Eingebettet

Fremdsprachen in Geschichte und Gegenwart Herausgegeben von Helmut Glück und Konrad Schröder Band 11,1 2013 Harrassowitz Verlag . Wiesbaden Paul Lévy Die deutsche Sprache in Frankreich Band 1: Von den Anfängen bis 1830 Aus dem Französischen übersetzt und bearbeitet von Barbara Kaltz 2013 Harrassowitz Verlag . Wiesbaden Gedruckt mit freundlicher Unterstützung der Stiftung Deutsche Sprache. Wissenschaftlicher Beirat: Csaba Földes, Mark Häberlein, Hilmar Hoffmann, Barbara Kaltz, Jochen Pleines, Libuše Špácˇilová, Harald Weinrich, Vibeke Winge. Titel der frz. Originalausgabe: Paul Lévy, La Langue allemande en France. Pénétration et diffusion des origines à nos jours: IAC, Lyon-Paris 1950-1952. Abbildung auf dem Umschlag: Straßburg um 1750 © akg-images. Bibliografische Information der Deutschen Nationalbibliothek Die Deutsche Nationalbibliothek verzeichnet diese Publikation in der Deutschen Nationalbibliografie; detaillierte bibliografische Daten sind im Internet über http://dnb.dnb.de abrufbar. Bibliographic information published by the Deutsche Nationalbibliothek The Deutsche Nationalbibliothek lists this publication in the Deutsche Nationalbibliografie; detailed bibliographic data are available in the internet at http://dnb.dnb.de Informationen zum Verlagsprogramm finden Sie unter http://www.harrassowitz-verlag.de © Otto Harrassowitz GmbH & Co. KG, Wiesbaden 2013 Das Werk einschließlich aller seiner Teile ist urheberrechtlich geschützt. Jede Verwertung außerhalb der engen Grenzen des Urheberrechtsgesetzes ist ohne Zustimmung des Verlages -

Handout 3 - Café Conversation Activity

Handout 3 - Café Conversation Activity Instructions: 1. Spread out the following eight pages on a desk, face down, and have every member of the group choose one page at random (it’s ok if there are pages remaining). 2. Each group member has 8-10 minutes to read about the person on the page they chose. Try to memorize the person’s name, their biography, and their major accomplishments. 3. After everyone is done reading, hold a conversation, as if you were meeting each person in the group for the first time at a party. Role play as the historical figure featured on the page chosen. Introduce yourself to the others in the group, and try to hold a conversation while considering how the historical figure you are representing might talk and respond. 4. Be prepared to share what you learned about one person you talked to during the café conversa- tion with the rest of the class. Name: Lyman Beecher Profession: Presbyterian Minister Dates: 1775-1863 Bio: Lyman Beecher was born in New Haven, Connecticut. He was raised by his uncle, who worked as a blacksmith and farmer. Beecher was an intellec- tually curious adolescent, and entered Yale University in 1793. After grad- uating, he studied at Yale Divinity School, and soon became an ordained minister. From there, Beecher worked in churches throughout New England before settling in Cincinnati, Ohio, in 1832. While Beecher did not participate in the camp meetings characteristic of the Second Great Awakening, he was involved in many of the social causes related to the revivals.