Recovery Spring Revisions EEH Final

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

SURVEY of CURRENT BUSINESS September 1935

SEPTEMBER 1935 OF CURRENT BUSINE UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF COMMERCE BUREAU OF FOREIGN AND DOMESTIC COMMERCE WASHINGTON VOLUME 15 NUMBER 9 Digitized for FRASER http://fraser.stlouisfed.org/ Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis UNITED STATES BUREAU OF MINES MINERALS YEARBOOK 1935 The First Complete Official Record Issued in 1935 A LIBRARY OF CURRENT DEVELOPMENTS IN THE MINERAL INDUSTRY (In One Volume) Survey of gold and silver mining and markets Detailed State mining reviews Current trends in coal and oil Analysis of the extent of business recovery for vari- ous mineral groups 75 Chapters ' 59 Contributors ' 129 Illustrations - about 1200 Pages THE STANDARD AUTHENTIC REFERENCE BOOK ON THE MINING INDUSTRY CO NT ENTS Part I—Survey of the mineral industries: Secondary metals Part m—Konmetals- Lime Review of the mineral industry Iron ore, pig iron, ferro'alloys, and steel Coal Clay Coke and byproducts Abrasive materials Statistical summary of mineral production Bauxite e,nd aluminum World production of minerals and economic Recent developments in coal preparation and Sulphur and pyrites Mercury utilization Salt, bromine, calcium chloride, and iodine aspects of international mineral policies Mangane.se and manganiferous ores Fuel briquets Phosphate rock Part 11—Metals: Molybdenum Peat Fuller's earth Gold and silver Crude petroleum and petroleum products Talc and ground soapstone Copper Tungsten Uses of petroleum fuels Fluorspar and cryolite Lead Tin Influences of petroleum technology upon com- Feldspar posite interest in oil Zinc ChroHHtt: Asbestos -

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany

Radio and the Rise of the Nazis in Prewar Germany Maja Adena, Ruben Enikolopov, Maria Petrova, Veronica Santarosa, and Ekaterina Zhuravskaya* May 10, 2014 How far can the media protect or undermine democratic institutions in unconsolidated democracies, and how persuasive can they be in ensuring public support for dictator’s policies? We study this question in the context of Germany between 1929 and 1939. Radio slowed down the growth of political support for the Nazis, when Weimar government introduced pro-government political news in 1929, denying access to the radio for the Nazis up till January 1933. This effect was reversed in 5 weeks after the transfer of control over the radio to the Nazis following Hitler’s appointment as chancellor. After full consolidation of power, radio propaganda helped the Nazis to enroll new party members and encouraged denunciations of Jews and other open expressions of anti-Semitism. The effect of Nazi radio propaganda varied depending on the listeners’ predispositions toward the message. Nazi radio was most effective in places where anti-Semitism was historically high and had a negative effect on the support for Nazi messages in places with historically low anti-Semitism. !!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!! * Maja Adena is from Wissenschaftszentrum Berlin für Sozialforschung. Ruben Enikolopov is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School, Moscow. Maria Petrova is from Barcelona Institute for Political Economy and Governance, Universitat Pompeu Fabra, Barcelona GSE, and the New Economic School. Veronica Santarosa is from the Law School of the University of Michigan. Ekaterina Zhuravskaya is from Paris School of Economics (EHESS) and the New Economic School. -

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945

Records of the Immigration and Naturalization Service, 1891-1957, Record Group 85 New Orleans, Louisiana Crew Lists of Vessels Arriving at New Orleans, LA, 1910-1945. T939. 311 rolls. (~A complete list of rolls has been added.) Roll Volumes Dates 1 1-3 January-June, 1910 2 4-5 July-October, 1910 3 6-7 November, 1910-February, 1911 4 8-9 March-June, 1911 5 10-11 July-October, 1911 6 12-13 November, 1911-February, 1912 7 14-15 March-June, 1912 8 16-17 July-October, 1912 9 18-19 November, 1912-February, 1913 10 20-21 March-June, 1913 11 22-23 July-October, 1913 12 24-25 November, 1913-February, 1914 13 26 March-April, 1914 14 27 May-June, 1914 15 28-29 July-October, 1914 16 30-31 November, 1914-February, 1915 17 32 March-April, 1915 18 33 May-June, 1915 19 34-35 July-October, 1915 20 36-37 November, 1915-February, 1916 21 38-39 March-June, 1916 22 40-41 July-October, 1916 23 42-43 November, 1916-February, 1917 24 44 March-April, 1917 25 45 May-June, 1917 26 46 July-August, 1917 27 47 September-October, 1917 28 48 November-December, 1917 29 49-50 Jan. 1-Mar. 15, 1918 30 51-53 Mar. 16-Apr. 30, 1918 31 56-59 June 1-Aug. 15, 1918 32 60-64 Aug. 16-0ct. 31, 1918 33 65-69 Nov. 1', 1918-Jan. 15, 1919 34 70-73 Jan. 16-Mar. 31, 1919 35 74-77 April-May, 1919 36 78-79 June-July, 1919 37 80-81 August-September, 1919 38 82-83 October-November, 1919 39 84-85 December, 1919-January, 1920 40 86-87 February-March, 1920 41 88-89 April-May, 1920 42 90 June, 1920 43 91 July, 1920 44 92 August, 1920 45 93 September, 1920 46 94 October, 1920 47 95-96 November, 1920 48 97-98 December, 1920 49 99-100 Jan. -

Presentation Slides

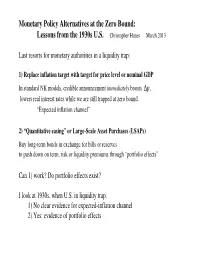

Monetary Policy Alternatives at the Zero Bound: Lessons from the 1930s U.S. Christopher Hanes March 2013 Last resorts for monetary authorities in a liquidity trap: 1) Replace inflation target with target for price level or nominal GDP In standard NK models, credible announcement immediately boosts ∆p, lowers real interest rates while we are still trapped at zero bound. “Expected inflation channel” 2) “Quantitative easing” or Large-Scale Asset Purchases (LSAPs) Buy long-term bonds in exchange for bills or reserves to push down on term, risk or liquidity premiums through “portfolio effects” Can 1) work? Do portfolio effects exist? I look at 1930s, when U.S. in liquidity trap. 1) No clear evidence for expected-inflation channel 2) Yes: evidence of portfolio effects Expected-inflation channel: theory Lessons from the 1930s U.S. β New-Keynesian Phillips curve: ∆p ' E ∆p % (y&y n) t t t%1 γ t T β a distant horizon T ∆p ' E [∆p % (y&y n) ] t t t%T λ j t%τ τ'0 n To hit price-level or $AD target, authorities must boost future (y&y )t%τ For any given path of y in near future, while we are still in liquidity trap, that raises current ∆pt , reduces rt , raises yt , lifts us out of trap Why it might fail: - expectations not so forward-looking, rational - promise not credible Svensson’s “Foolproof Way” out of liquidity trap: peg to depreciated exchange rate “a conspicuous commitment to a higher price level in the future” Expected-inflation channel: 1930s experience Lessons from the 1930s U.S. -

A Prairie Parable the 1933 Bates Tragedy

University of Nebraska - Lincoln DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln Great Plains Quarterly Great Plains Studies, Center for 2009 A Prairie Parable The 1933 Bates Tragedy Bill Walser University of Saskatchewan Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly Part of the Other International and Area Studies Commons Walser, Bill, "A Prairie Parable The 1933 Bates Tragedy" (2009). Great Plains Quarterly. 1235. https://digitalcommons.unl.edu/greatplainsquarterly/1235 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Great Plains Studies, Center for at DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. It has been accepted for inclusion in Great Plains Quarterly by an authorized administrator of DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska - Lincoln. A PRAIRIE PARABLE THE 1933 BATES TRAGEDY BILL WAlSER It was one of the more harrowing episodes of as a relief case. But it was only the child who the Great Depression. Ted and Rose Bates had died when the suicide plan went terribly wrong, failed in business in Glidden, Saskatchewan, in and the parents were charged with murder and 1932 and again on the west coast of Canada the brought to trial in the spring of 1934. following year. When they were subsequently The sorry tale of the Bates family has come turned down for relief assistance twice, first to epitomize the collateral damage wrought in Vancouver and then in Saskatoon, because by the collapse of rural Saskatchewan during they did not meet the local residency require the Great Depression of the 1930s. A popu ments, the couple decided to end their lives in lar Canadian university-level textbook, for a remote rural schoolyard, taking their eight example, uses the tragedy to open the chapter year-old son, Jackie, with them rather than on the Depression.1 Trent University historian face the shame of returning home to Glidden James Struthers, on other hand, employs the incident as an exclamation point. -

The Political Economy of Argentina's Abandonment

Going through the labyrinth: the political economy of Argentina’s abandonment of the gold standard (1929-1933) Pablo Gerchunoff and José Luis Machinea ABSTRACT This article is the short but crucial history of four years of transition in a monetary and exchange-rate regime that culminated in 1933 with the final abandonment of the gold standard in Argentina. That process involved decisions made at critical junctures at which the government authorities had little time to deliberate and against which they had no analytical arsenal, no technical certainties and few political convictions. The objective of this study is to analyse those “decisions” at seven milestone moments, from the external shock of 1929 to the submission to Congress of a bill for the creation of the central bank and a currency control regime characterized by multiple exchange rates. The new regime that this reordering of the Argentine economy implied would remain in place, in one form or another, for at least a quarter of a century. KEYWORDS Monetary policy, gold standard, economic history, Argentina JEL CLASSIFICATION E42, F4, N1 AUTHORS Pablo Gerchunoff is a professor at the Department of History, Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected] José Luis Machinea is a professor at the Department of Economics, Torcuato Di Tella University, Buenos Aires, Argentina. [email protected] 104 CEPAL REVIEW 117 • DECEMBER 2015 I Introduction This is not a comprehensive history of the 1930s —of and, if they are, they might well be convinced that the economic policy regarding State functions and the entrance is the exit: in other words, that the way out is production apparatus— or of the resulting structural to return to the gold standard. -

Inflation Expectations and Recovery from the Depression in the Spring of 1933: Evidence from the Narrative Record

Inflation Expectations and Recovery from the Depression in the Spring of 1933: Evidence from the Narrative Record Andrew J. Jalil and Gisela Rua* January 2016 Abstract This paper uses the historical narrative record to determine whether inflation expectations shifted during the second quarter of 1933, precisely as the recovery from the Great Depression took hold. First, by examining the historical news record and the forecasts of contemporary business analysts, we show that inflation expectations increased dramatically. Second, using an event- studies approach, we identify the impact on financial markets of the key events that shifted inflation expectations. Third, we gather new evidence—both quantitative and narrative—that indicates that the shift in inflation expectations played a causal role in stimulating the recovery. JEL Classification: E31, E32, E12, N42 Keywords: inflation expectations, Great Depression, narrative evidence, liquidity trap, regime change * Andrew Jalil: Department of Economics, Occidental College, 1600 Campus Road, Los Angeles, CA 90041 (email: [email protected]). Gisela Rua: Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System, Mail Stop 82, 20th St. and Constitution Ave. NW, Washington, D.C. 20551 (email: [email protected]). We are grateful to Pamfila Antipa, Alan Blinder, Michael Bryan, Chia-Ying Chang, Tracy Dennison, Barry Eichengreen, Joshua Hausman, Philip Hoffman, John Leahy, David Lopez-Salido, Christopher Meissner, Edward Nelson, Marty Olney, Jonathan Rose, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, Jeremy Rudd, Eugene White, our discussants Carola Binder and Hugh Rockoff, and seminar participants at the Federal Reserve Board, the Federal Reserve Bank of San Francisco, the Reserve Bank of New Zealand, the California Institute of Technology, American University, and Occidental College for thoughtful comments. -

The Frontier, May 1933

University of Montana ScholarWorks at University of Montana The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 University of Montana Publications 5-1933 The Frontier, May 1933 Harold G. Merriam Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier Let us know how access to this document benefits ou.y Recommended Citation Merriam, Harold G., "The Frontier, May 1933" (1933). The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939. 44. https://scholarworks.umt.edu/frontier/44 This Journal is brought to you for free and open access by the University of Montana Publications at ScholarWorks at University of Montana. It has been accepted for inclusion in The Frontier and The Frontier and Midland Literary Magazines, 1920-1939 by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks at University of Montana. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ■ MAY, 1933 ■ H R 9 MAGAZINE O f THE NORTHWE ST BLACK ■ | M O T H ER A Story by Elma Godchaux RING-TAILED R fA R ER S H f i ■ V. L. O, CKittick ! ■ !-------------- , WE TALK ABOUT REGIONALISM: NORTH, EAST, SOUTH, AND WEST I Ben A . Botkin FORTY CENTS WESTERN MONTANA t f S R t f i e Scenic Empire ^ Sitoated approximately midway between tbe two great National Glacier, Missoula literally may be said to b e m me heart of tbe Scenic Empire of theNorfchwest In H directions out of B Garden City of Montana are places of marvelous. beauty. Entering Missoula from the Bast, tbe pas- s e ^ e r on either of the two great transconiahental lines/ Milwaukee R B Pacific, or the automobile, tourist winds "for miles through Hellgate Oanypu. -

Commodity Price Movements in 1936 by Roy G

March 1937 March 1937 SURVEY OF CURRENT BUSINESS 15 Commodity Price Movements in 1936 By Roy G. Blakey, Chief, Division of Economic Research HANGES in the general level of wholesale prices to 1933 also rose most rapidly during 1936 as they did C during the first 10 months of 1936 were influenced in the preceding 3 years. (See fig. 1.) mostly by the fluctuations of agricultural prices, with The annual index of food prices was 1.9 percent lower nonagricultural prices moving approximately horizon- for 1936 than for 1935, but the index of farm products tally. Agricultural prices, after having risen sharply as was 2.7 percent and the index of prices of all commodi- a result of the 1934 drought, moved lower during the ties other than farm products and foods was 2.2 per- first 4% months of 1936 on prospects for increased INDEX NUMBERS (Monthly average, 1926= lOO) supplies. When the 1936 trans-Mississippi drought 1201 • • began to appear serious, however, agricultural prices turned up sharply and carried the general price average -Finished Products with them. The rapid rise during the summer was suc- / ceeded by a lull in September and October, but imme- 60 diately following the November election there was a -Row Maferia/s sharp upward movement of most agricultural prices at the same time that a marked rise in nonagricultural products was experienced. The net result of these 1929 1930 1952 1934 I9?6 divergent movements was a 1-percent increase in the Figure 1.—Wholesale Prices by Economic Classes, 1929-36 (United 1936 annual average of the Bureau of Labor Statistics States Department of Labor). -

1933–1941, a New Deal for Forest Service Research in California

The Search for Forest Facts: A History of the Pacific Southwest Forest and Range Experiment Station, 1926–2000 Chapter 4: 1933–1941, A New Deal for Forest Service Research in California By the time President Franklin Delano Roosevelt won his landslide election in 1932, forest research in the United States had grown considerably from the early work of botanical explorers such as Andre Michaux and his classic Flora Boreali- Americana (Michaux 1803), which first revealed the Nation’s wealth and diversity of forest resources in 1803. Exploitation and rapid destruction of forest resources had led to the establishment of a federal Division of Forestry in 1876, and as the number of scientists professionally trained to manage and administer forest land grew in America, it became apparent that our knowledge of forestry was not entirely adequate. So, within 3 years after the reorganization of the Bureau of Forestry into the Forest Service in 1905, a series of experiment stations was estab- lished throughout the country. In 1915, a need for a continuing policy in forest research was recognized by the formation of the Branch of Research (BR) in the Forest Service—an action that paved the way for unified, nationwide attacks on the obvious and the obscure problems of American forestry. This idea developed into A National Program of Forest Research (Clapp 1926) that finally culminated in the McSweeney-McNary Forest Research Act (McSweeney-McNary Act) of 1928, which authorized a series of regional forest experiment stations and the undertaking of research in each of the major fields of forestry. Then on March 4, 1933, President Roosevelt was inaugurated, and during the “first hundred days” of Roosevelt’s administration, Congress passed his New Deal plan, putting the country on a better economic footing during a desperate time in the Nation’s history. -

Special Libraries, August 1933

San Jose State University SJSU ScholarWorks Special Libraries, 1933 Special Libraries, 1930s 8-1-1933 Special Libraries, August 1933 Special Libraries Association Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1933 Part of the Cataloging and Metadata Commons, Collection Development and Management Commons, Information Literacy Commons, and the Scholarly Communication Commons Recommended Citation Special Libraries Association, "Special Libraries, August 1933" (1933). Special Libraries, 1933. 7. https://scholarworks.sjsu.edu/sla_sl_1933/7 This Book is brought to you for free and open access by the Special Libraries, 1930s at SJSU ScholarWorks. It has been accepted for inclusion in Special Libraries, 1933 by an authorized administrator of SJSU ScholarWorks. For more information, please contact [email protected]. "PUTTING KNOWLEDGE TO WORK" VOLUME24 AUGUST, 1933 &UMBER..7 Some Problems Raised by NRA BY CHARLESR. ERDMAN, JR. ...................139 University Research in Public Administration BY /ONE M. ELY ..........................141 Public Administration-Its Significance to Research Workers By REBECCARANKIN ....................... .I44 The Princeton Survey .........................I45 Responsibility of the Library for Con- . servation of Local Documents By JOSEPH~NEB. HOLLINGSWORTH............... 146 Municipal Finance Research I By EDNA TRULL............................ 148 I President's Page ............................ .I49 Snips and Snipes ........................... .I49 What to Read ..............................151 SPECIAL LIBRARIES published monthly March to October, with bi-monthly issuer January- February and November-December, by The Special Libraries Association at-10 Ferry Street, Concord, N. H. Editorial, Advertis~ng and Subscription Offices at 345 Hudson Street, New York, N. Y. Subscription price: $5.00 a year; foreign $5.50, s~nglecopter, 50 cents. Entered as second-clasr matter at the Post Oheat Concord, N. -

University Archives Inventory

University Archives Inventory Record Group Number: UR001.03 Title: Burney Lynch Parkinson Presidential Records Date: 1926-1969 Bulk Date: 1932-1952 Extent: 42 boxes Creator: Burney Lynch Parkinson Administrative/Biographical Notes: Burney Lynch Parkinson (1887-1972) was an educator from Lincoln, Tennessee. He received his B.S. from Erskine College in 1909, and rose up the administrative ranks from English teacher in Laurens, South Carolina public schools. He received his M.A. from Peabody College in 1920, and Ph.D. from Peabody in 1926, after which he became president of Presbyterian College in Clinton, SC in 1927. He was employed as Director of Teacher Training, Certification, and Elementary Education at the Alabama Dept. of Education just before coming to MSCW to become president in 1932. In December 1932, the university was re-accredited by the Southern Association of Colleges and Schools, ending the crisis brought on the purge of faculty under Governor Theodore Bilbo, but appropriations to the university were cut by 54 percent, and faculty and staff were reduced by 33 percent, as enrollment had declined from 1410 in 1929 to 804 in 1932. Parkinson authorized a study of MSCW by Peabody college, ultimately pursuing its recommendations to focus on liberal arts at the cost of its traditional role in industrial, vocational, and technical education. Building projects were kept to a minimum during the Parkinson years. Old Main was restored and named for Mary Calloway in 1938. Franklin Hall was converted to a dorm, and the Whitfield Gymnasium into a student center with the Golden Goose Tearoom inside. Parkinson Hall was constructed in 1951 and named for Dr.