Defense Planning in a Time of Conflict a Comparative Analysis of the 2001–2014 Quadrennial Defense Reviews, and Implications for the Army

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Defense 2020 “Covid-19 and the U.S. Military”

Center for Strategic and International Studies TRANSCRIPT Defense 2020 “Covid-19 and the U.S. Military” RECORDING DATE Wednesday, April 1, 2020 GUESTS Steve Morrison Senior Vice President, and Director, Global Health Policy Center, CSIS Mark Cancian Senior Advisor, International Security Program, CSIS Christine Wormuth Director, International Security and Defense Policy Center, RAND Corporation Christine Wormuth Director, International Security and Defense Policy Center, RAND Corporation HOST Rear Admiral (Ret.) Tom Cullison Former Deputy Surgeon General of the U.S. Navy, and Adjunct Fellow, Global Health Policy Center, CSIS Transcript by Rev.com Kathleen Hicks: Hi, I'm Kathleen Hicks, Senior Vice President and Director of the International Security Program at the Center for Strategic and International Studies, and this is Defense 2020 a CSIS podcast examining critical defense issues in the United States is 2020 election cycle. We bring in defense experts from across the political spectrum to survey the debates over the US military strategy, missions and funding. This podcast is made possible by contributions from BAE systems, Lockheed Martin, Northrop Grumman, and the Thales Group. Kathleen Hicks: On this episode of Defense 2020, I hosted discussion with four experts on COVID-19 and the US military. Steve Morrison, Senior Vice President and Director of Global Health Policy at CSIS, Mark Cancian, Senior Advisor in the International Security Program at CSIS, Christine Wormuth, Director of the International Security and Defense Policy Center at the RAND Corporation and Rear Admiral (Ret.), Tom Cullison Former Deputy Surgeon General of the US Navy and an Adjunct Fellow in the Global Health Policy Center at CSIS. -

United States Policy and Military Strategy in the Middle East

S. HRG. 114–350 UNITED STATES POLICY AND MILITARY STRATEGY IN THE MIDDLE EAST HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 24; SEPTEMBER 22; OCTOBER 27, 2015 ( Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:53 Sep 08, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00001 Fmt 6011 Sfmt 6011 C:\USERS\WR47328\DESKTOP\21401.TXT WILDA UNITED STATES POLICY AND MILITARY STRATEGY IN THE MIDDLE EAST VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:53 Sep 08, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00002 Fmt 6019 Sfmt 6019 C:\USERS\WR47328\DESKTOP\21401.TXT WILDA S. HRG. 114–350 UNITED STATES POLICY AND MILITARY STRATEGY IN THE MIDDLE EAST HEARINGS BEFORE THE COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES UNITED STATES SENATE ONE HUNDRED FOURTEENTH CONGRESS FIRST SESSION MARCH 24; SEPTEMBER 22; OCTOBER 27, 2015 Printed for the use of the Committee on Armed Services ( Available via the World Wide Web: http://www.fdsys.gov/ U.S. GOVERNMENT PUBLISHING OFFICE 21–401 PDF WASHINGTON : 2016 For sale by the Superintendent of Documents, U.S. Government Publishing Office Internet: bookstore.gpo.gov Phone: toll free (866) 512–1800; DC area (202) 512–1800 Fax: (202) 512–2104 Mail: Stop IDCC, Washington, DC 20402–0001 VerDate Nov 24 2008 10:53 Sep 08, 2016 Jkt 000000 PO 00000 Frm 00003 Fmt 5011 Sfmt 5011 C:\USERS\WR47328\DESKTOP\21401.TXT WILDA COMMITTEE ON ARMED SERVICES JOHN MCCAIN, Arizona, Chairman JAMES M. INHOFE, Oklahoma JACK REED, Rhode Island JEFF SESSIONS, Alabama BILL NELSON, Florida ROGER F. -

Whither America? a Strategy for Repairing America’S Political Culture

Whither America? A Strategy for Repairing America’s Political Culture John Raidt Foreword by Ellen O. Tauscher Whither America? A Strategy for Repairing America’s Political Culture Atlantic Council Strategy Paper No. 13 © 2017 The Atlantic Council of the United States. All rights reserved. No part of this publi- cation may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means without permission in writing from the Atlantic Council, except in the case of brief quotations in news articles, critical articles, or reviews. Please direct inquiries to: Atlantic Council 1030 15th Street, NW, 12th Floor Washington, DC 20005 ISBN: 978-1-61977-383-7 Cover art credit: Abraham Lincoln by George Peter Alexander Healy, 1869 This report is written and published in accordance with the Atlantic Council Policy on Intel- lectual Independence. The authors are solely responsible for its analysis and recommenda- tions. The Atlantic Council, its partners, and funders do not determine, nor do they necessari- ly endorse or advocate for, any of this report’s particular conclusions. November 2017 Atlantic Council Strategy Papers Editorial Board Executive Editors Mr. Frederick Kempe Dr. Alexander V. Mirtchev Editor-in-Chief Mr. Barry Pavel Managing Editor Dr. Mathew Burrows Table of Contents FOREWORD ....................................................................................................................i EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................2 WHITHER AMERICA? ...............................................................................................10 -

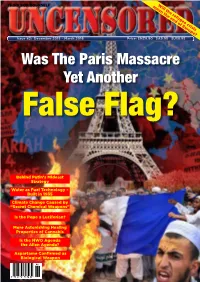

Was the Paris Massacre Yet Another False Flag?

mean Will the the end refugee of Europe? crisis THINK FOR YOURSELF Issue 42: December 2015 – March 2016 Price: $NZ9.90 $A9.95 $US8.95 Was The Paris Massacre Yet Another False Flag? Behind Putin’s Mideast Strategy Water as Fuel Technology – Built in 1935 Climate Change Caused by “Secret Chemical Weapons” Is the Pope a Luciferian? More Astonishing Healing Properties of Cannabis Is the NWO Agenda the Alien Agenda? ALSOAspartame IN THIS ConfirmedISSUE ... as Biological Weapon 42 REALITY GOT YOU DOWN? Issue 1: COLLECTOR’S EDITION “I’d rather have a free bottle in If you start feeling front of me better about yourself, than a prefrontal you’re not thinking. lobotomy.” “Why spend good money on candles, when it’s cheaper to curse the darkness?” A woman’s place is in the home. A man’s place is in a vicious, inhumane, totalitarian corporation. “If it weren’t for pickpockets I’d have no sex life at all.” NOW! WITH EXTRA SARCASM AT NO EXTRA COST!!! Price: $5.95 The Pessimist’s Book of Wisdom By Jonathan Eisen (Editor of Uncensored) Only $10 (includes P/H to NZ and Australia). Please post your order (cheques or credit card details) to: The Full Court Press Ltd. PO Box 44-128, Pt Chevalier, Auckland 1246, NZ “If people in the media cannot de- cide whether they are in the busi- “Instead of the triumph of democracy and progress, we got violence, poverty and social disaster. Nobody cares a bit about ness of reporting news or manu- human rights, including the right to life. -

Senate Passes Garment.Liabilt Mean AFL-CIO to His Opposition to Make Entie Health Plan

Labor Calls on LegislatuirE00posi elegates from throughout D the state convene at Sacra- mento Monday to review the cur- rent session of.the Legislature in the light of needs and aspirations of the two million California wage earners represented by urnons of the AFL-CIO. The annual Legislative Confer- ence opens at 9:30 a.m. Monday at Vol 37-No. 19 -My2,19 the -Sacramento Radisson Hotel with a review of pending bills inter- mixed with remarks by key political leaders. Health .A highlight will be an address by Martin Manley, Assistant U.S. Sec- retary of Labor, during the confer- Crisis. ence dinner Tuesday evening at the hotel. Monday's discussions of bills will T,aAx on be led by Jack Henning, executive secretary-treasurer of, the California Labor Federation, and Bob Bal- Benefits genorth, president of the State The labor movement has launch- Building and Construction Trades ed a grass-roots lobbying campaign Council of California. The two or- against a proposal to attach taxes on ganizations jointly sponsor the current employee health benefits to conference. the national health care refonn now State Treasurer Kathleen Brown, being debated in Congress. labor's endorsed candidate for gov- The problem is in the House ernor, will speak to the delegates Ways and Means Committee where during the opening session. Others Republicans and some conservative who will speak are Lieutenant Gov- Democrats are trying to impose ernor Leo McCarthy, Senate Presi- such a tax, Executive Secretary- dent Pro-Tem Bill Lockyer, Assem- Treasurer Jack Henning warned bly Speaker Willie L. -

Key Officials September 1947–July 2021

Department of Defense Key Officials September 1947–July 2021 Historical Office Office of the Secretary of Defense Contents Introduction 1 I. Current Department of Defense Key Officials 2 II. Secretaries of Defense 5 III. Deputy Secretaries of Defense 11 IV. Secretaries of the Military Departments 17 V. Under Secretaries and Deputy Under Secretaries of Defense 28 Research and Engineering .................................................28 Acquisition and Sustainment ..............................................30 Policy ..................................................................34 Comptroller/Chief Financial Officer ........................................37 Personnel and Readiness ..................................................40 Intelligence and Security ..................................................42 VI. Specified Officials 45 Cost Assessment and Program Evaluation ...................................45 General Counsel of the Department of Defense ..............................47 Inspector General of the Department of Defense .............................48 VII. Assistant Secretaries of Defense 50 Acquisition ..............................................................50 Health Affairs ...........................................................50 Homeland Defense and Global Security .....................................52 Indo-Pacific Security Affairs ...............................................53 International Security Affairs ..............................................54 Legislative Affairs ........................................................56 -

Annual Report

ANNUAL REPORT January 2020 740 15th Street, NW Suite 900 Washington, D.C. 20005 [email protected] http://presidentsalliance.org/ Cover photo: Rally for DACA at the Supreme Court, November 12, 2019 Credit: Scott Henrichsen/University of California Presidents’ Alliance | Annual Report 2 Table of Contents A Message from Our Steering Committee Our Mission Presidents’ Alliance at a Glance Activities & Impact Our Supporters & Funders Our Alliance Steering Committee Members Staff Legal Advisory Council Federal Policy Advisory Table Presidents’ Alliance | Annual Report 3 A Message from Our Steering Committee Dear colleagues and friends, Greetings! We are pleased to report in these pages on the progress of our Alliance and its accomplishments in the past year. In only its second year of operation, the Alliance is doing exceptional work helping presidents and campuses bring their voices and perspectives to bear on immigration issues playing out in the courts, Congress and the administration -- matters that directly impact our students, campuses and communities. With your support, the Alliance is able to help campus leaders and our many allies stay up to date on these fast-changing developments in immigration policies and practices, coordinate actions and activities in response, and plan for future opportunities to engage on these matters. It is a true privilege to be able to work together with you to build this Alliance as part of our shared commitment to supporting immigrant and international students. The growing roll of college and university presidents who are part of the Alliance attests to the importance of these issues for our campuses and communities and to the value presidents find in being part of the Alliance. -

U.S.-China Military Contacts: Issues for Congress

U.S.-China Military Contacts: Issues for Congress Shirley A. Kan Specialist in Asian Security Affairs October 27, 2014 Congressional Research Service 7-5700 www.crs.gov RL32496 U.S.-China Military Contacts: Issues for Congress Summary This CRS Report, updated through the 113th Congress, discusses policy issues regarding military- to-military (mil-to-mil) contacts with the People’s Republic of China (PRC) and records major contacts and crises since 1993. The United States suspended military contacts with China and imposed sanctions on arms sales in response to the Tiananmen Crackdown in 1989. In 1993, President Clinton reengaged with the top PRC leadership, including China’s military, the People’s Liberation Army (PLA). Renewed military exchanges with the PLA have not regained the closeness reached in the 1980s, when U.S.-PRC strategic alignment against the Soviet Union included U.S. arms sales to China. Improvements and deteriorations in overall bilateral engagement have affected military contacts, which were close in 1997-1998 and 2000, but marred by the 1995-1996 Taiwan Strait crisis, mistaken NATO bombing of a PRC embassy in 1999, the EP-3 aircraft collision crisis in 2001, and the PLA’s aggressive maritime and air confrontations. Issues for Congress include whether the Administration complies with legislation overseeing dealings with the PLA and pursues contacts with the PLA that advance a prioritized set of U.S. security interests, especially the operational safety of U.S. military personnel. Oversight legislation includes the Foreign Relations Authorization Act for FY1990-FY1991 (P.L. 101-246) and National Defense Authorization Act (NDAA) for FY2000 (P.L. -

Program Guide Sponsored By

AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION Program Guide sponsored by EXPANDING THE COMPETITIVE EDGE September 16-18, 2019 | National Harbor, MD | AFA.org Cover outer gatefold (in PDF only, this page intentionally left blank) AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION It takes collaboration and innovation to win in the multi-domain battlespace Program Guide sponsored by of the future. In the battlespace of tomorrow, success will depend on synchronized networks that rapidly EXPANDING integrate data sources and weapon systems across domains. Working together to outpace, disrupt and paralyze your adversary, multi-domain superiority is closer than you think. THE COMPETITIVE EDGE Learn more at lockheedmartin.com. September 16-18, 2019 | National Harbor, MD | AFA.org © 2019 Lockheed Martin Corporation Live: N/A Trim: W: 7.9375in H: 10.875in Job Number: FG18-23208_044b Bleed: H: .125in all sides Designer: Kevin Gray Publication: AFA Program Guide Gutter: None Communicator: Ryan Alford Visual: F-35C Resolution: 300 DPI Due Date: 7/22/19 Country: USA Density: 300 Color Space: CMYK Lethal. Survivable. Connected. The U.S. Air Force’s combat proven F-35A is the most lethal, survivable and connected fighter in the world. With stealth, advanced sensors, and networked data links, the F-35 can go where no fighter can go, see what no fighter can see and share unprecedented information with the joint, multi-domain fighting force. Supersonic speed. Fighter agility. Increased range. Extended mission persistence. Flexible weapons capacity. From the highest-end, sensitive missions to permissive battlespace. On the first day to the last. The F-35 gives the U.S. Air Force a decisive advantage, ensuring our men and women in uniform can execute their mission and return home safe every time, no matter the threat. -

Remembering Holy Cross Hall Former Residents, Rectors Reflect on Life by St

.-------------------------------~------·~--------·--~~----------------------~~ Sooner or later one of us must go Picking up steam The Irish take on the Oklahoma Sooners Former ND visiting professor Bill Bradley's Friday Saturday. Check out the Irish Insider for presidential campaign gets another boost after predictions, starting lineups and the lowdown Thursday's fundraising report. OCTOBER!, on both teams. News+ page 10 Irish Insider 1999 THE The Independent Newspaper Serving Notre Dame and Saint Mary's VOL XXXIII NO. 28 HTTP://OBSERVER.ND.EDU Dust to Dust: Remembering Holy Cross Hall Former residents, rectors reflect on life by St. Marys Lake They were into protesting the Vietnam By FINN PRESSLY War and into the peace movement, so they Assistant News Editor liked the setting and the fact that they had their own environment," said Pete A father brought his family to the shore LaFleur, who was the last president of the of St. Mary's Lake one fall morning, intent hall. on showing them the building where he Holy Cross developed a reputation for spent his four years at Notre Da'me. being a close-knit community on the fringe Thinking he had lost his way, he sheepish of Notre Dame's residence life - a reputa ly asked a passing student for directions to tion enhanced by its secluded location his former residence hall. between the lakes. He left that day without pictures of his "When you consider how close the other old dorm, his old room, and his old hang residence halls are to each other and to outs, but rather with a picture of a barren the dining halls . -

The Evolution of the Civil Affairs Force

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Calhoun, Institutional Archive of the Naval Postgraduate School Calhoun: The NPS Institutional Archive Theses and Dissertations Thesis Collection 2013-12 The evolution of the Civil Affairs force Ferry, John V. Monterey, California: Naval Postgraduate School http://hdl.handle.net/10945/38928 NAVAL POSTGRADUATE SCHOOL MONTEREY, CALIFORNIA THESIS THE EVOLUTION OF THE CIVIL AFFAIRS FORCE by John V. Ferry Benny H. Romero December 2013 Thesis Co-advisors: George Lober Camber Warren Approved for public release; distribution is unlimited THIS PAGE INTENTIONALLY LEFT BLANK REPORT DOCUMENTATION PAGE Form Approved OMB No. 0704–0188 Public reporting burden for this collection of information is estimated to average 1 hour per response, including the time for reviewing instruction, searching existing data sources, gathering and maintaining the data needed, and completing and reviewing the collection of information. Send comments regarding this burden estimate or any other aspect of this collection of information, including suggestions for reducing this burden, to Washington headquarters Services, Directorate for Information Operations and Reports, 1215 Jefferson Davis Highway, Suite 1204, Arlington, VA 22202–4302, and to the Office of Management and Budget, Paperwork Reduction Project (0704–0188) Washington, DC 20503. 1. AGENCY USE ONLY (Leave blank) 2. REPORT DATE 3. REPORT TYPE AND DATES COVERED December 2013 Master’s Thesis 4. TITLE AND SUBTITLE 5. FUNDING NUMBERS THE EVOLUTION OF THE CIVIL AFFAIRS FORCE 6. AUTHOR(S) John V. Ferry and Benny H. Romero 7. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION NAME(S) AND ADDRESS(ES) 8. PERFORMING ORGANIZATION Naval Postgraduate School REPORT NUMBER Monterey, CA 93943–5000 9. -

Aerospace Nation Air, Space & Cyber Forces in the Fight

AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION Attendee Guide sponsored by AEROSPACE NATION AIR, SPACE & CYBER FORCES IN THE FIGHT September 14-16, 2020 | AFA.org Together we are transforming the battlespace and the business. In the battlespace of tomorrow, success depends on synchronized networks that rapidly integrate data and systems across all domains. At Lockheed Martin, DevSecOps software development, modular open systems architectures and digital engineering are making this future possible. So that together, we outpace and paralyze our adversaries. Learn more at lockheedmartin.com/afa-2020 ©2020 Lockheed Martin Corporation FG19-23960_031 AFA_JADO.indd 1 Live: n/a 8/25/20 5:31 PM Trim: W: 10.875 H: 8.125 Job Number: FG19-23960_031 Designer: Sam Coplen Bleed: H: 0.125 Publication: AFA Communicator: Carla Gutter: None Visual: Multi-Domain-Operations Krivanek Resolution: 300 DPI Country: USA Due Date: 8/25/20 Density: 300 Color Space: CMYK AIR FORCE ASSOCIATION I. Introduction Welcome _________________________________________________________________2 Welcome Messages from vASC Platinum Sponsors ________________________________3 List of Exhibitors ___________________________________________________________5 Individual Benefactors ______________________________________________________13 II. Air, Space & Cyber Conference Schedule of Events _________________________________________________________17 Speaker Biographies _______________________________________________________21 AFA Supporting Partners ____________________________________________________39 In Memoriam