Paper + Appendix

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empty Tomb

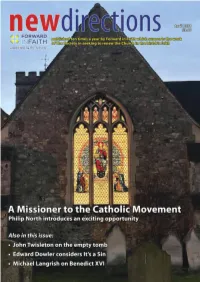

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

7 X 11.5 Three Lines.P65

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-19744-1 - The Jew, the Cathedral, and the Medieval City: Synagoga and Ecclesia in the Thirteenth Century Nina Rowe Index More information S Index Aachen, 152, 162 Ekbert von Andechs-Meran, bishop, 150, 151, Alan of Lille, 216, 225 152–3, 161, 162–3, 164, 165, 175, 185, Albigensian Crusade, 123 187–9, 274n14, 275n25, 276n46, 277n50 Albrecht I, emperor, 226 Otto II von Andechs-Meran, bishop, 152, 188 Albrecht von Käferberg, archbishop of Magdeburg, Poppo von Andechs-Meran, provost and 187 bishop, 150–1, 163, 175, 185, 188, 189, Alexander II, pope, 25 274n14 Alsace, 166, 214, 219, 229–30, 231, 247, 288n111 structure and adornment Altercatio Ecclesiae et Synagogae. See pseudo-Augustine Adamspforte, 146, 155 Amiens angel installed at eastern choir, 160 cathedral of, 99 Bamberg Rider, 2, 10, 147, 148, 155, 156, 160, diocese of, 120 162, 164, 165, 176, 179, 182–3, 187–90, Andechs-Meran family, 152–3, 188 281n111, 281n112 Andlau, imperial castle at, 230 construction history of building, 153, 162–3 Andrew, king of Hungary, 152 Devil blinding Jew, 140, 146, 172, 176, 178 Annales marbacenses, 231 Ecclesia and Synagoga at, 2–6, 10, 15, 39, 40, antiquity, medieval interest in, 5, 9, 52, 55–8, 82–4, 81–4, 140, 147–8, 155–9, 162, 164–5, 169, 98–103, 159–62, 164, 185, 211–12 172, 176, 178, 179–85, 187–8, 189–90, 191, Aphrodisias, Sebasteion at, 42–4 211, 213, 229, 236, 239, 241, 242, 243 Armleder massacres. See Jews, attacks on Fürstenportal, 140–1, 146–7, 150, 153–6, Assizes of Messina, 166 158–9, 162, 163–5, 169–72, -

Building of Christendom Pdf, Epub, Ebook

BUILDING OF CHRISTENDOM PDF, EPUB, EBOOK Warren H. Carroll | 616 pages | 15 Nov 2004 | Christendom Press Books | 9780931888243 | English | Front Royal, United States Building of Christendom PDF Book As the Western Roman Empire disintegrated into feudal kingdoms and principalities , the concept of Christendom changed as the western church became one of five patriarchates of the Pentarchy and the Christians of the Eastern Roman Empire developed. Main articles: History of science in the Renaissance and Renaissance technology. Developments in western philosophy and European events brought change to the notion of the Corpus Christianum. In Protestant churches , where the proclamation of God's Word is of special importance, the visitor's line of view is directed towards the pulpit. Christendom at Wikipedia's sister projects. The Church gradually became a defining institution of the Empire. Main article: Basilica. But thanks to the Church scholars such as Aquinas and Buridan , the West carried on at least the spirit of scientific inquiry which would later lead to Europe's taking the lead in science during the Scientific Revolution using translations of medieval works. Rachel rated it it was amazing May 31, Archived from the original on 2 February This is a story of faith, of failure, and of ultimate salvation. Joseph Scott Amis rated it really liked it Jan 13, CIA world facts. The notion of "Europe" and the " Western World " has been intimately connected with the concept of "Christianity and Christendom"; many even attribute Christianity for being the link that created a unified European identity. Random House Publishing Group. February Andrew Dickson White Eric Jackson rated it it was amazing Oct 08, Harcourt, Brace and Company. -

ST. HENRY CATHOLIC CHURCH 24750 W. Lower Buckeye Rd

ST. HENRY CATHOLIC CHURCH 24750 W. Lower Buckeye Rd. Buckeye, AZ 85326 July 12, 2020 CLERGY SUNDAY MASS SCHEDULE Fr. William J. Kosco, Pastor Saturday Vigil . 5:00pm Fr. Kevin Penkalski, Sábado (Español) . 7:00pm Parochial Vicar Sunday . 8:00am Dcn. Mark Gribowski 10:00am Dcn. Victor León Domingo (Español) . 12:00pm Dcn. Nick Bonaiuto Prayer For a New . (Español) . 6:00pm Parish Home Receptionist Lord, help us in our endeavor to Flor de liz López build a new home. Enlighten us to DAILY MASS see how You are leading us, both SCHEDULE Secretary as a Church and as a family. Nancy Vela Through the intercession of Mon. Tue. Thurs. Fri. 8:30am St. Henry, we ask for guidance and Wednesday . 12:00pm noon inspiration during this journey of faith so that the fruit of our labor may live on for many CONFESSIONS generations. OFFICE HOURS Amen Wednesday 3:00 - 5:00pm Oración Por un Nuevo Hogar Monday - Friday Parroquial ADORATION 9:00am - 12:00pm Señor, ayúdanos en nuestro es- fuerzo de construir un nuevo ho- Wednesday 1:00 - 5:00pm gar. Ilumínanos, para ver como Tú Parish Office: nos guías como Iglesia y como fa- www.sthenrybuckeye.com milia. Por medio de la intercesión de San Enrique, Te pedimos nos Facebook: (623) 386-0175 guíes y nos inspires durante esta jornada de fe, a fin de que el fruto St. Henry Catholic Church E-mail: de nuestra labor perdure para mu- chas generaciones. Buckeye, AZ [email protected] Amen July 12, 2020 Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Our Patron: St. -

Management Plan for the UNESCO World Heritage Site “Town of Bamberg”

Management Plan for the UNESCO World Heritage site “Town of Bamberg” 1 PUBLISHING INFORMATION Commissioned by City of Bamberg World Heritage Office Untere Mühlbrücke 5 96047 Bamberg Germany www.welterbe.bamberg.de/en Conceptual Development Bamberg World Heritage Office Patricia Alberth M.Sc. (Editor-in-Chief) Hannah Röhlen M.A. Diana Büttner, Dipl.Ing.(FH), M.A.(Univ.) Hannah Gröner M.A. Process Design and Support michael kloos planning and heritage consultancy Prof. Dr-Ing. Michael Kloos Baharak Seyedashrafi M.A. Philipp Tebart, Dipl.-Ing. Lothringerstrasse 95 52070 Aachen Germany www.michaelkloos.de Visual Space Analysis Peter Eisenlauer, Dipl.-Ing. Architektur & Stadtplanung Tengstrasse 32 80796 Munich Germany www.eisenlauer-muenchen.de Layout _srgmedia Stefan Gareis Translation Rachel Swift © 2019 2 FOREWORD Unique, authentic, deserving of preservation – for 26 years now the Town of Bamberg has been a designated UNESCO World Heritage site. Alongside the Great Wall of China, Machu Picchu and other important sites, it numbers among the over one thousand cultural and natural sites worldwide which have been acknowledged as having an Outstanding Universal Value by UNESCO the cultural organization of the United Nations. In order to improve the communication, decision-making and operational processes in all matters related to our World Heritage, Bamberg City Council resolved in 2014 to commission a new Management Plan for the UNESCO World Heritage site “Town of Bamberg”. This plan is now complete. It is an important planning instrument, vital for the protection, use, maintenance and sustainable development of the Bamberg World Heritage site. The World Heritage Manage- ment Plan is also a requirement of UNESCO. -

Iv G Kili Iz Chimera of Arezzo

G kili iz Chimera of Arezzo iv ABSTRACT Gothic sculpture in the understanding of art was arranged in arrays solemn church next to the main door. The church was decorated with sculptures describing the outer surface of the subjects received the Torah and the Bible. Artists, they have achieved a mastery Perceiving the structure of the body underneath clothes folds gradually. In the 12th century the main task of the sculptor was to try to northern cathedrals. The best examples of 14th century sculpture sculptures were made from precious metals and ivory to private chapels. to avoid the inclination to figure giving the impression stiffness was also achieved in this century. Although the statue after the first listen associated with mortals only began to be described; It passed from one figure to many figures. 13 sculptures tended to look like mortal men after century. Mary, just as a holy woman, he played as a host. British gothic architecture depends on the statue but was given after the 13th century. In Germany, the sculpture was always starting from Bamberg Cathedral weight. German sculpture increasingly more connected to nature, took an independent direction. The most important of Gothic sculpture made in understanding art and alarm Gargoyle Chimera. In this study, it has spread to the branches of which were the subject of understanding and Gothic art, which means that the load times have also been told that in our culture works remaining from the Ottoman period and that period. In the last chapter " Chimera of Arezzo " sculpture is also studied . This statue, which is a people who migrated from Italy has been a major factor in both the Greek and Italian selected to host the Asian culture and craftsmanship. -

Gothic Europe 12-15Th C

Gothic Europe 12-15th c. The term “Gothic” was popularized by the 16th c. artist and historian Giorgio Vasari who attributed the style to the Goths, Germanic invaders who had “destroyed” the classical civilization of the Roman empire. In it’s own day the Gothic style was simply called “modern art” or “The French style” Gothic Age: Historical Background • Widespread prosperity caused by warmer climate, technological advances such as the heavy plough, watermills and windmills, and population increase . • Development of cities. Although Europe remained rural, cities gained increasing prominence. They became centers of artistic patronage, fostering communal identity by public projects and ceremonies. • Guilds (professional associations) of scholars founded the first universities. A system of reasoned analysis known as scholasticism emerged from these universities, intent on reconciling Christian theology and Classical philosophy. • Age of cathedrals (Cathedral = a church that is the official seat of a bishop) • 11-13th c - The Crusades bring Islamic and Byzantine influences to Europe. • 14th c. - Black Death killing about one third of population in western Europe and devastating much of Europe’s economy. Europe About 1200 England and France were becoming strong nation-states while the Holy Roman Empire was weakened and ceased to be a significant power in the 13th c. French Gothic Architecture The Gothic style emerged in the Ile- de-France region (French royal domain around Paris) around 1140. It coincided with the emergence of the monarchy as a powerful centralizing force. Within 100 years, an estimate 2700 Gothic churches were built in the Ile-de-France alone. Abbot Suger, 1081-1151, French cleric and statesman, abbot of Saint- Denis from 1122, minister of kings Louis VI and Louis VII. -

Franconia Art and Architecture in Germany’S Medieval Heartland

MARTIN RANDALL TRAVEL ART • ARCHITECTURE • GASTRONOMY • ARCHAEOLOGY • HISTORY • MUSIC • LITERATURE Franconia Art and architecture in Germany’s medieval heartland 20–27 June 2022 (mi 400) 8 days • £2,960 Lecturer: Dr Jarl Kremeier A neglected region of southern Germany which has an exceptional heritage of art and architecture, enchanting streetscape and natural beauty. Medieval art including Romanesque sculpture (the Bamberg Rider) and late medieval wood carving by Tilman Riemenschneider. Baroque and Rococo palaces, churches and paintings, including Tiepolo’s masterpiece. Once the very heart of the medieval German kingdom, Franconia possesses some of the loveliest towns and villages in Germany, beautiful countryside and a variety of art and architecture of the highest quality. Yet remarkably few Britons find their way here – or could even point to the region on a map. Coburg Castle and Park, from Germany, by E T & E Harrison Compton, 1912 Würzburg, with its vine-clad riverbanks and Baroque palaces, is a delight. The tour stays here for two nights. One of the loveliest and Itinerary changed in appearance for hundreds of years; least spoilt of German towns, Bamberg has fine the church of St James has Riemenschneider’s streetscape, riverside walks and picturesque Day 1: Würzburg. Fly at c. 9.30am from Last Supper. Visit Schloss Weissenstein in upper town around the Romanesque cathedral. London Heathrow to Frankfurt (Lufthansa). Pommersfelden, an early 18th-century country Nuremberg, the home of Dürer, was one of the Drive to Würzburg, and check in to the hotel. house with one of the grandest of Baroque great cities of the Middle Ages, and its churches An afternoon walk to the oldest medieval staircases. -

What the Middle Ages Knew Gothic Art Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018

What the Middle Ages knew Gothic Art Piero Scaruffi Copyright 2018 http://www.scaruffi.com/know 1 What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Economic prosperity – Growing independence of towns from feudal lords – Intellectual fervor of cathedral schools and scholastics – Birth of the French nation-state 2 What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Pointed arch (creative freedom in designing bays) – Rib vault (St Denis, Paris) – Flying buttress (Chartres, France) 3 (Suger’s choir, St Denis, Paris) What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Consequences: • High naves • Campaniles, towers, spires: vertical ascent • Large windows (walls not needed for support) • Stained glass windows • Light 4 What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Consequences: • The painting (and its biblical iconography) moves from the church walls to the glass windows 5 What the Middle Ages knew • Architectural styles of the Middle Ages 6 Lyon-Rowen- Hameroff: A History of the Western World What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic architecture – Consequences: • Stained glass windows (Chartres, France) 7 What the Middle Ages knew • Gothic – 1130: the most royal church is a monastery (St Denis), not a cathedral – Suger redesigns it on thelogical bases (St Denis preserved the mystical manuscript attributed to Dionysus the Aeropagite) – St Denis built at the peak of excitement for the conquest of Jerusalem (focus on Jesus, the one of the three persons that most mattered to the crusaders) – St Denis built on geometry and arithmetics (influence of Arab -

Romanesque Architecture and Its Artistry in Central Europe, 900-1300

Romanesque Architecture and its Artistry in Central Europe, 900-1300 Romanesque Architecture and its Artistry in Central Europe, 900-1300: A Descriptive, Illustrated Analysis of the Style as it Pertains to Castle and Church Architecture By Herbert Schutz Romanesque Architecture and its Artistry in Central Europe, 900-1300: A Descriptive, Illustrated Analysis of the Style as it Pertains to Castle and Church Architecture, by Herbert Schutz This book first published 2011 Cambridge Scholars Publishing 12 Back Chapman Street, Newcastle upon Tyne, NE6 2XX, UK British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library Copyright © 2011 by Herbert Schutz All rights for this book reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise, without the prior permission of the copyright owner. ISBN (10): 1-4438-2658-8, ISBN (13): 978-1-4438-2658-7 To Barbara TABLE OF CONTENTS List of Illustrations ..................................................................................... ix List of Maps........................................................................................... xxxv Acknowledgements ............................................................................. xxxvii Introduction ................................................................................................. 1 Chapter One................................................................................................ -

ST. HENRY CATHOLIC CHURCH 24750 W. Lower

ST. HENRY CATHOLIC CHURCH 24750 W. Lower Buckeye Rd. Buckeye, AZ 85326 July 15, 2018 St. Henry, MASS SCHEDULE King of Germany Saturday Vigil . 5:00pm Emperor of the Sábado (Español) . 7:00pm Holy Roman Empire Sunday . 8:00am Feast Day, July 13th 10:00am Domingo (Español) . 12:00pm Born in 972 CONFESSIONS Bavaria, Germany Wednesday 4:00 5:00pm Died in 1024 Saturday 3:00 4:30pm ADORATION Wednesday 1:00 5:00pm San Enrique, OFFICE HOURS Rey de Alemania Monday Thursday 9:00am 5:00pm Emperador del Santo CLERGY Imperio Romano Fr. William J. Kosco, Pastor Día Festivo, julio 13 Fr. Ryan Lee, Parochial Vicar Nació el año 972 Dcn. Mark Gribowski Bavaria, Alemania Dcn. Victor León Dcn. Nick Bonaiuto Falleció en 1024 Receptionist Parish Office: (623) 3860175 Flor de liz López, x 101 Email: [email protected] www.sthenrybuckeye.com Secretary Facebook: St. Henry Catholic Church, Buckeye, AZ Nancy Vela, x 102 DAILY MASS SCHEDULE Monday, Thursday & Friday 8:30am Tuesday 5:00pm & Wednesday 12Noon July 15, 2018 Fifteenth Sunday in Ordinary Time Sacramental Preparation for Children and Teenagers FOUNDATIONS COURSE AGE: 17 grade ENROLLMENT: October 2018 Enrollment for children currently in 17 grade in the “Foundations” Sacramen- tal Preparation class begins with a 12week course for parents only in the Spring of 2019. Children enter the program in the Fall of 2019 upon the par- Saturday July 14 ents’ completion of the adult course. Children will receive their Sacraments of 5:00 pm Elisa Ott Confirmation & Holy Communion in the Spring of 2020. The course is free of 7:00 pm +Maria Luisa Sanchez charge.