Booklet for the State Exhibition

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Empty Tomb

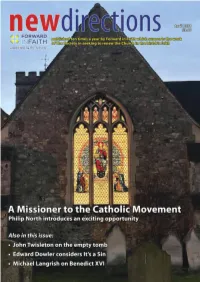

content regulars Vol 24 No 299 April 2021 6 gHOSTLy cOunSEL 3 LEAD STORy 20 views, reviews & previews AnDy HAWES A Missioner to the catholic on the importance of the church Movement BOOkS: Christopher Smith on Philip North introduces this Wagner 14 LOST SuffOLk cHuRcHES Jack Allen on Disability in important role Medieval Christianity EDITORIAL 18 Benji Tyler on Being Yourself BISHOPS Of THE SOcIETy 35 4 We need to talk about Andy Hawes on Chroni - safeguarding cles from a Monastery A P RIEST 17 APRIL DIARy raises some important issues 27 In it from the start urifer emerges 5 The Empty Tomb ALAn THuRLOW in March’s New Directions 19 THE WAy WE LIvE nOW JOHn TWISLETOn cHRISTOPHER SMITH considers the Resurrection 29 An earthly story reflects on story and faith 7 The Journal of Record DEnIS DESERT explores the parable 25 BOOk Of THE MOnTH WILLIAM DAvAgE MIcHAEL LAngRISH writes for New Directions 29 Psachal Joy, Reveal Today on Benedict XVI An Easter Hymn 8 It’s a Sin 33 fAITH Of OuR fATHERS EDWARD DOWLER 30 Poor fred…Really? ARTHuR MIDDLETOn reviews the important series Ann gEORgE on Dogma, Devotion and Life travels with her brother 9 from the Archives 34 TOucHIng PLAcE We look back over 300 editions of 31 England’s Saint Holy Trinity, Bosbury Herefordshire New Directions JOHn gAyfORD 12 Learning to Ride Bicycles at champions Edward the Confessor Pusey House 35 The fulham Holy Week JAck nIcHOLSOn festival writes from Oxford 20 Still no exhibitions OWEn HIggS looks at mission E R The East End of St Mary's E G V Willesden (Photo by Fr A O Christopher Phillips SSC) M I C Easter Chicks knitted by the outreach team at Articles are published in New Directions because they are thought likely to be of interest to St Saviour's Eastbourne, they will be distributed to readers. -

Herzlich Willkommen

Welcome Paul Bomke Chief Executive Officer (CEO) Pfalzklinikum Agenda The special status… …who we are… …what is important for us and how it continues? Our mission… Mental health services in the Palatinate, Germany …the special status difficult conditions for taboos stigmatization social exclusion prevention information of the public Who we are community services/ inclusion as a mission patient resident inpatient outpatient and day- services people care services client guest participation, rehabilitation and work Where we are Rockenhausen Kusel Kaiserslautern Maikammer Speyer Rodalben Annweiler Pirmasens Landau Bellheim Dahn Klingenmünster Bad Bergzabern Wörth Numbers and facts: 2199 employees, turnover 110,8 Mio. € (2017), 1.134 beds and places Mental health services and prevention departments psychiatry, psychotherapy, psychosomatics (children, adolescents, adults) neurology, forensic treatment for psychiatric offenders, outpatient services, psychiatric community services, “The Palatinate makes itself/you strong – ways to resilience”) status as of 06/2018 Our services of psychiatry, psychotherapy, psychosomatics and neurology in the Palatinate Kusel Day-care clinic and psychiatric institutional outpatients' department (PIA), mental health group North-West Palatinate; outpatient psychiatric care Rockenhausen Rockenhausen (Day-care) clinic and psychiatric institutional outpatients' department (PIA), mental health group Kusel North-West Palatinate; outpatient psychiatric care Kaiserslautern (Day-care) clinic and psychiatric institutional -

Welche Politiker Sind Die Größten Klimasünder?

Welche Politiker sind die größten Klimasünder? CO2-Ausstoß, Motorisierung und Spritverbrauch der Dienstwagen der Bundesminister "Gelbe Karte" für positive Ansätze bei CO2-Reduktion CO - Verbrauch Verbrauch Höchstge- 2 Motorleistung Rang Ministerium Bundesminister Fahrzeug Ausstoß innerstädtisch kombiniert Baujahr schwindigkeit [PS] [g/km] [l/100km] [l/100km] [km/h] Sabine Leutheusser- 1 BMJ Audi A6 3.0 TDI quattro (Diesel) 149 6,7 5,7 204 2012 240 Schnarrenberger 2 BMAS Dr. Ursula von der Leyen Audi A8 L 3.0 TDI quattro (Diesel) 171 7,9 6,5 250 2012 250 2 BMVBS Dr. Peter Ramsauer Audi A8 L 3.0 TDI quattro (Diesel) 171 7,9 6,5 250 2012 250 4 BMU Dr. Norbert Röttgen Audi A8 L 3.0 TDI quattro (Diesel) 176 8,0 6,6 250 2011 250 4 BMFSFJ Dr. Kristina Schröder Audi A8 L 3.0 TDI quattro (Diesel) 176 8,0 6,6 250 2011 250 4 BMBF Prof. Dr. Annette Schavan Audi A8 L 3.0 TDI quattro (Diesel) 176 8,0 6,6 250 2011 250 4 BMWi Dr. Philipp Rösler Audi A8 L 3.0 TDI quattro (Diesel) 176 8,0 6,6 250 2011 250 8 BMELV Ilse Aigner BMW 730Ld (Diesel) 180 9,1 6,9 245 2011 245 8 BMZ Dirk Niebel BMW 730Ld (Diesel) 180 9,1 6,9 245 2011 245 10 BMG Daniel Bahr BMW 740d xDrive (Diesel) 183 8,8 7,0 306 2011 250 Quelle: DUH-Recherche Februar bis April 2012. Bei mehreren Dienstfahrzeugen wurde das Fahrzeug mit dem höchsten CO2-Ausstoß gewertet. -

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and The

The Capital Sculpture of Wells Cathedral: Masons, Patrons and the Margins of English Gothic Architecture MATTHEW M. REEVE For Eric Fernie This paper considers the sculpted capitals in Wells cathedral. Although integral to the early Gothic fabric, they have hitherto eluded close examination as either a component of the building or as an important cycle of ecclesiastical imagery in their own right. Consideration of the archaeological evidence suggests that the capitals were introduced mid-way through the building campaigns and were likely the products of the cathedral’s masons rather than part of an original scheme for the cathedral as a whole. Possible sources for the images are considered. The distribution of the capitals in lay and clerical spaces of the cathedral leads to discussion of how the imagery might have been meaningful to diCerent audiences on either side of the choir screen. introduction THE capital sculpture of Wells Cathedral has the dubious honour of being one of the most frequently published but least studied image cycles in English medieval art. The capitals of the nave, transepts, and north porch of the early Gothic church are ornamented with a rich array of figural sculptures ranging from hybrid human-animals, dragons, and Old Testament prophets, to representations of the trades that inhabit stiC-leaf foliage, which were originally highlighted with paint (Figs 1, 2).1 The capitals sit upon a highly sophisticated pier design formed by a central cruciform support with triple shafts at each termination and in the angles, which oCered the possibility for a range of continuous and individual sculpted designs in the capitals above (Fig. -

Obtaining World Heritage Status and the Impacts of Listing Aa, Bart J.M

University of Groningen Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing Aa, Bart J.M. van der IMPORTANT NOTE: You are advised to consult the publisher's version (publisher's PDF) if you wish to cite from it. Please check the document version below. Document Version Publisher's PDF, also known as Version of record Publication date: 2005 Link to publication in University of Groningen/UMCG research database Citation for published version (APA): Aa, B. J. M. V. D. (2005). Preserving the heritage of humanity? Obtaining world heritage status and the impacts of listing. s.n. Copyright Other than for strictly personal use, it is not permitted to download or to forward/distribute the text or part of it without the consent of the author(s) and/or copyright holder(s), unless the work is under an open content license (like Creative Commons). Take-down policy If you believe that this document breaches copyright please contact us providing details, and we will remove access to the work immediately and investigate your claim. Downloaded from the University of Groningen/UMCG research database (Pure): http://www.rug.nl/research/portal. For technical reasons the number of authors shown on this cover page is limited to 10 maximum. Download date: 23-09-2021 Appendix 4 World heritage site nominations Listed site in May 2004 (year of rejection, year of listing, possible year of extension of the site) Rejected site and not listed until May 2004 (first year of rejection) Afghanistan Península Valdés (1999) Jam, -

A Historical Review and Quantitative Analysis of International Criminal Justice

CHAPTER TWELVE A HISTORICAL REVIEW AND QUANTITATIVE ANALYSIS OF INTERNATIONAL CRIMINAL JUSTICE Section 1. The Historical Stages of International Criminal Justice ICJ made its way into international practice in several stages. The first period ranges from 1268 until 1815, effectively from the first international criminal pros- ecution of Conradin von Hohenstaufen in Naples through the end of World War I. The second stage begins with the signing of the Treaty of Versailles and ranges from 1919 until 2014, when it is expected that all of the existing direct and mixed model tribunals will have closed, leaving only the International Criminal Court (ICC). The third impending stage will begin in January 2015, when the ICC will be the primary international criminal tribunal. 1.1. The Early Historic Period—Thirteenth to Nineteenth Centuries The first period, which could prosaically be called the early historic period, is characterized by three major events occurring in 1268, 1474, and 1815, respectively. In 1268, the trial of Conradin von Hohenstaufen, a German nobleman, took place in Italy when Conradin was sixteen years of age.1 He was tried and exe- cuted for transgressing the Pope’s dictates by attacking a fellow noble French ruler, wherein he pillaged and killed Italian civilians at Tagliacozzo, near Naples. The killings were deemed to constitute crimes “against the laws of God and Man.” The trial was essentially a political one. In fact, it was a perversion of ICJ and demonstrated how justice could be used for political ends. The crime— assuming it can be called that—was in the nature of a “crime against peace,” as that term came to be called in the Nuremberg Charter’s Article 6(a), later to be called aggression under the UN Charter. -

Treasures of Mankind in Hessen

Hessen State Ministry of Higher Education, Research and the Arts United Nations World Heritage Educational, Scientific and in Germany Cultural Organization Treasures of Mankind in Hessen UNESCO World Cultural Heritage · World Natural Heritage · World Documentary Heritage Hessisches Ministerium für Wissenschaft und Kunst Hessen State Ministry of Higher Education, Research and the Arts Mark Kohlbecher Presse- und Öffentlichkeitsarbeit Rheinstraße 23 – 25 65185 Wiesbaden Germany www.hmwk.hessen.de Landesamt für Denkmalpflege Hessen Hessen State Office for the Preservation of Historic Monuments Prof. Dr. Gerd Weiß UNESCO-Welterbebeauftragter des Landes Präsident des Landesamtes für Denkmalpflege in Hessen Schloss Biebrich Rheingaustraße 140 65203 Wiesbaden Germany www.denkmalpflege-hessen.de CONTENTS 1 Editorial · Boris Rhein 2 Heritage is a commitment Introduction · Prof. Dr. Gerd Weiß 4 Protecting and preserving WORLD CULTURAL HERITAGE Gateway to the Early Middle Ages 6 Lorsch Abbey A romantic river 10 Upper Middle Rhine Valley The frontier of the Roman Empire 14 Upper German-Raetian Limes The primeval force of water 18 Bergpark Wilhelmshöhe WORLD NATURAL HERITAGE The Pompeii of Palaeontology 22 Messel Pit Fossil Site Publication details: Leaving nature to its own devices 26 Published by: The Hessen Ministry of Higher Education, Research and the Arts • Rheinstraße 23 – 25 • Ancient Beech Forests of Germany: the Kellerwald 65185 Wiesbaden • Germany • Editor: Gabriele Amann-Ille • Authors: Gabriele Amann-Ille, Dr. Ralf Breyer, Dr. Reinhard Dietrich, Kathrin Flor, Dr. Michael Matthäus, Dr. Hermann Schefers, Jutta Seuring, Dr. Silvia WORLD DOCUMENTARY HERITAGE Uhlemann, Dr. Jennifer Verhoeven, Jutta Zwilling • Layout: Christiane Freitag, Idstein • Illustrations: Title A modern classic 30 page: top row, from left to right: Saalburg: Saalburg archive; Messel Fossil Pit: Darmstadt State Museum; Burg Fritz Lang’s silent film “Metropolis” Ehrenfels: Rüdesheim Tourist AG, photo: K. -

Human Rights and History a Challenge for Education

edited by Rainer Huhle HUMAN RIGHTS AND HISTORY A CHALLENGE FOR EDUCATION edited by Rainer Huhle H UMAN The Universal Declaration of Human Rights and the Genocide Convention of 1948 were promulgated as an unequivocal R response to the crimes committed under National Socialism. Human rights thus served as a universal response to concrete IGHTS historical experiences of injustice, which remains valid to the present day. As such, the Universal Declaration and the Genocide Convention serve as a key link between human rights education and historical learning. AND This volume elucidates the debates surrounding the historical development of human rights after 1945. The authors exam- H ine a number of specific human rights, including the prohibition of discrimination, freedom of opinion, the right to asylum ISTORY and the prohibition of slavery and forced labor, to consider how different historical experiences and legal traditions shaped their formulation. Through the examples of Latin America and the former Soviet Union, they explore the connections · A CHALLENGE FOR EDUCATION between human rights movements and human rights education. Finally, they address current challenges in human rights education to elucidate the role of historical experience in education. ISBN-13: 978-3-9810631-9-6 © Foundation “Remembrance, Responsibility and Future” Stiftung “Erinnerung, Verantwortung und Zukunft” Lindenstraße 20–25 10969 Berlin Germany Tel +49 (0) 30 25 92 97- 0 Fax +49 (0) 30 25 92 -11 [email protected] www.stiftung-evz.de Editor: Rainer Huhle Translation and Revision: Patricia Szobar Coordination: Christa Meyer Proofreading: Julia Brooks and Steffi Arendsee Typesetting and Design: dakato…design. David Sernau Printing: FATA Morgana Verlag ISBN-13: 978-3-9810631-9-6 Berlin, February 2010 Photo Credits: Cover page, left: Stèphane Hessel at the conference “Rights, that make us Human Beings” in Nuremberg, November 2008. -

The ECSC Common Assembly's Decision to Create Political Groups Writing a New Chapter in Transnational Parliamentary History

BRIEFING European Parliament History Series The ECSC Common Assembly's decision to create political groups Writing a new chapter in transnational parliamentary history SUMMARY Political groups in the European Parliament contribute greatly to the institution's supranational character and are a most important element of its parliamentary work. Moreover, the Parliament's political groups have proven to be crucial designers of EU politics and policies. However, when the forerunner of today's Parliament, the Common Assembly of the Coal and Steel Community (ECSC), was established in 1952, the creation of political groups was not envisaged at all. Making use of its autonomy with regard to writing its rules of procedures, the ECSC Common Assembly unanimously decided, at its plenary session in June 1953, to allow the creation of political groups. With this decision, the ECSC Common Assembly became the world's first international assembly organised in political groups. This briefing analyses the decision of the ECSC Common Assembly to create political groups by bringing together political and historical science literature on the topic, as well as original sources from the Parliament's Historical Archives that record considerations and motives for the decision to create political groups. It will illustrate the complementary cultural, historical, organisational and financial reasons for this decision. Furthermore, it will demonstrate that, for the first ECSC Common Assembly members, it was highly important to take account of political affiliations in order to highlight the supranational character of the newly emerging Assembly. Finally, the briefing highlights that common work within the political groups was essential in helping to overcome early difficulties between the Assembly's members with different national backgrounds. -

Theories and Images of Creation in Northern Europe in the Twelfth Century

Art History ISSN 0141-6790 Vol. 22 No. 1 March 1999 pp. 3-55 In the Beginning: Theories and images of creation in Northern Europe in the twelfth century Conrad Rudolph 'Logic has made me hated by the world!' So Peter Abelard thought and wrote to his former lover, the brilliant Heloise, in probably his last letter to her before his death in 1142, after having been virtually driven from Paris by Bernard of Clairvaux, the austere Cistercian mystic and perhaps the most powerful ecclesiastical politician of Western Europe.1 Characteristically for Abelard in matters of self-conception, he was exaggerating. Logic had made him hated not by the world but by only a portion of it. While this was certainly an influential portion and one that had almost succeeded in destroying him, it could never do so entirely. In fact, logic had made Abelard 'the Socrates of the Gauls, the great Plato of the West, our Aristotle ... the prince of scholars'2- and this, this great fame and the almost unprecedented influence that accompanied it, was as much the problem as logic was. In a word, Abelard had been caught up in the politics of theology. The time was one of great theological inquiry, challenging, as it did, the very authority of divine revelation on the most fundamental level, and at a moment when both interest in secular learning and the number of students were dramatically increasing - all factors that can hardly be over-emphasized. But for certain elements within the Church, more still was at stake. And this was nothing less than a perceived assault on one of the basic underpinnings of the complex relationship between religion, theology, society and political power. -

The First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux

CISTERCIAN FATHERS SERIES: NUMBER SEVENTY-SIX THE FIRST LIFE OF BERNARD OF CLAIRVAUX CISTERCIAN FATHERS SERIES: NUMBER SEVENTY-SIX The First Life of Bernard of Clairvaux by William of Saint-Thierry, Arnold of Bonneval, and Geoffrey of Auxerre Translated by Hilary Costello, OCSO Cistercian Publications www.cistercianpublications.org LITURGICAL PRESS Collegeville, Minnesota www.litpress.org A Cistercian Publications title published by Liturgical Press Cistercian Publications Editorial Offices 161 Grosvenor Street Athens, Ohio 45701 www.cistercianpublications.org In the absence of a critical edition of Recension B of the Vita Prima Sancti Bernardi, this translation is based on Mount Saint Bernard MS 1, with section numbers inserted from the critical edition of Recension A (Vita Prima Sancti Bernardi Claraevallis Abbatis, Liber Primus, ed. Paul Verdeyen, CCCM 89B [Turnhout: Brepols Publishers, 2011]). Scripture texts in this work are translated by the translator of the text. The image of Saint Bernard on the cover is a miniature from Mount Saint Bernard Abbey, fol. 1, reprinted with permission from Mount Saint Bernard Abbey. © 2015 by Order of Saint Benedict, Collegeville, Minnesota. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form, by print, microfilm, microfiche, mechanical recording, photocopying, translation, or any other means, known or yet unknown, for any purpose except brief quotations in reviews, without the previous written permission of Liturgical Press, Saint John’s Abbey, PO Box 7500, College- ville, Minnesota 56321-7500. Printed in the United States of America. 123456789 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Vita prima Sancti Bernardi. English The first life of Bernard of Clairvaux / by William of Saint-Thierry, Arnold of Bonneval, and Geoffrey of Auxerre ; translated by Hilary Costello, OCSO. -

Holy Roman Emperors

Holy Roman Emperors 791 818 846 873 901 928 955 983 1010 1038 1065 1092 1120 1147 1174 1202 1229 1257 1284 1311 1339 1366 1393 1421 1448 1476 1503 1530 1558 1585 1612 1640 1667 1695 1722 1749 1777 1804 Lothair I, Carolingian Henry II of Saxony, holy Great Interregnum, Holy Habsburg dynasty of the Francis I, Habsburg holy holy roman emperor roman emperor Roman Empire Holy Roman Empire roman emperor Guy of Spoleto, holy Henry IV, Salian holy Adolf of Nassau, holy Charles V, Habsburg holy roman emperor roman emperor roman emperor roman emperor Conrad III of Conrad I of Franconia, Frederick III, Habsburg Matthias, Habsburg holy Hohenstaufen, holy roman holy roman emperor holy roman emperor roman emperor emperor Carolingian dynasty of Otto I of Saxony, holy Otto IV, Welf holy roman Rupert of Wittelsbach, Joseph I, Habsburg holy the Holy Roman Empire roman emperor emperor holy roman emperor roman emperor Richard, Earl of Louis II, Carolingian Salian dynasty of the Albert II, Habsburg holy Joseph II, Habsburg holy Cornwall, holy roman holy roman emperor Holy Roman Empire roman emperor roman emperor emperor Lambert of Spoleto, holy Henry V, Salian holy Albert I, Habsburg holy Ferdinand I, Habsburg roman emperor roman emperor roman emperor holy roman emperor Frederick I (Barbarossa) Berengar, Carolingian Louis IV of Wittelsbach, Ferdinand II, Habsburg of Hohenstaufen, holy holy roman emperor holy roman emperor holy roman emperor roman emperor Charlemagne (Charles I), Frederick II of Otto II of Saxony, holy Jobst of Luxembourg, Charles VI, Habsburg