Structure from Motion Photogrammetry Enhances Paleontological Resource Documentation, Research, Preservation and Education Efforts for National Park Service Areas

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

And Early Jurassic Sediments, and Patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic

and Early Jurassic sediments, and patterns of the Triassic-Jurassic PAUL E. OLSEN AND tetrapod transition HANS-DIETER SUES Introduction parent answer was that the supposed mass extinc- The Late Triassic-Early Jurassic boundary is fre- tions in the tetrapod record were largely an artifact quently cited as one of the thirteen or so episodes of incorrect or questionable biostratigraphic corre- of major extinctions that punctuate Phanerozoic his- lations. On reexamining the problem, we have come tory (Colbert 1958; Newell 1967; Hallam 1981; Raup to realize that the kinds of patterns revealed by look- and Sepkoski 1982, 1984). These times of apparent ing at the change in taxonomic composition through decimation stand out as one class of the great events time also profoundly depend on the taxonomic levels in the history of life. and the sampling intervals examined. We address Renewed interest in the pattern of mass ex- those problems in this chapter. We have now found tinctions through time has stimulated novel and com- that there does indeed appear to be some sort of prehensive attempts to relate these patterns to other extinction event, but it cannot be examined at the terrestrial and extraterrestrial phenomena (see usual coarse levels of resolution. It requires new fine- Chapter 24). The Triassic-Jurassic boundary takes scaled documentation of specific faunal and floral on special significance in this light. First, the faunal transitions. transitions have been cited as even greater in mag- Stratigraphic correlation of geographically dis- nitude than those of the Cretaceous or the Permian junct rocks and assemblages predetermines our per- (Colbert 1958; Hallam 1981; see also Chapter 24). -

Orbital Pacing and Secular Evolution of the Early Jurassic Carbon Cycle

Orbital pacing and secular evolution of the Early Jurassic carbon cycle Marisa S. Storma,b,1, Stephen P. Hesselboc,d, Hugh C. Jenkynsb, Micha Ruhlb,e, Clemens V. Ullmannc,d, Weimu Xub,f, Melanie J. Lengg,h, James B. Ridingg, and Olga Gorbanenkob aDepartment of Earth Sciences, Stellenbosch University, 7600 Stellenbosch, South Africa; bDepartment of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, OX1 3AN Oxford, United Kingdom; cCamborne School of Mines, University of Exeter, TR10 9FE Penryn, United Kingdom; dEnvironment and Sustainability Institute, University of Exeter, TR10 9FE Penryn, United Kingdom; eDepartment of Geology, Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland; fDepartment of Botany, Trinity College Dublin, The University of Dublin, Dublin 2, Ireland; gEnvironmental Science Centre, British Geological Survey, NG12 5GG Nottingham, United Kingdom; and hSchool of Biosciences, University of Nottingham, LE12 5RD Loughborough, United Kingdom Edited by Lisa Tauxe, University of California San Diego, La Jolla, CA, and approved January 3, 2020 (received for review July 14, 2019) Global perturbations to the Early Jurassic environment (∼201 to where they are recorded as individual shifts or series of shifts ∼174 Ma), notably during the Triassic–Jurassic transition and Toar- within stratigraphically limited sections. Some of these short-term cian Oceanic Anoxic Event, are well studied and largely associated δ13C excursions have been shown to represent changes in the with volcanogenic greenhouse gas emissions released by large supraregional to global carbon cycle, marked by synchronous igneous provinces. The long-term secular evolution, timing, and changes in δ13C in marine and terrestrial organic and inorganic pacing of changes in the Early Jurassic carbon cycle that provide substrates and recorded on a wide geographic extent (e.g., refs. -

The Global Stratotype Sections and Point (GSSP) for the Base of the Jurassic System at Kuhjoch (Karwendel Mountains, Northern Calcareous Alps, Tyrol, Austria)

162 162 Articles by Hillebrandt, A.v.1, Krystyn, L.2, Kürschner, W.M.3, Bonis, N.R.4, Ruhl, M.5, Richoz, S.6, Schobben, M. A. N.12, Urlichs, M.7, Bown, P.R.8, Kment, K.9, McRoberts, C.A.10, Simms, M.11, and Tomãsových, A13 The Global Stratotype Sections and Point (GSSP) for the base of the Jurassic System at Kuhjoch (Karwendel Mountains, Northern Calcareous Alps, Tyrol, Austria) 1 Institut für Angewandte Geowissenschaften, Technische Universität, Ernst-Reuter-Platz 1, 10587 Berlin, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 2 Department for Palaeontology, Vienna University, Geozentrum, Althansstr. 9, A-1090 Vienna, Austria. E-mail: [email protected] 3 Department of Geosciences and Centre of Earth Evolution and Dynamics (CEED), University of Oslo, PO box 1047, Blindern, 0316 Oslo, Norway. E-mail: [email protected] 4 Shell Global Solutions International B.V., Kessler Park 1, 2288 GS, Rijswijk, the Netherlands. E-mail: [email protected] 5 Department of Earth Sciences, University of Oxford, South Parks Road, Oxford OX1 3AN, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 6 Commission for the Palaeontological and Stratigraphical Research of Austria, Austrian Academy of Sciences c/o Institut of Earth Sciences, Graz University, Heinrichstraße 26, 8010 Graz, Austria. E-mail: [email protected] 7 Staatliches Museum für Naturkunde, Rosenstein 1, 70191 Stuttgart, Germany. E-mail: [email protected] 8 Department of Earth Sciences, University College London, Gower Street, London WC1E 6BT, UK. E-mail: [email protected] 9 Lenggrieser Str. -

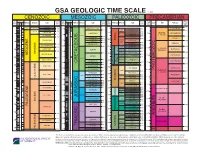

GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE V

GSA GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE v. 4.0 CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST HIST. ANOM. (Ma) ANOM. CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 66.0 541 CALABRIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE* 1.8 31 C31 MAASTRICHTIAN 252 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 Lopin- 254 32 C32 72.1 635 2A C2A PIACENZIAN WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 3.6 gian 33 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN CAPITANIAN NEOPRO- 5 C3 CAMPANIAN Guada- 265 750 CRYOGENIAN 5.3 80 C33 WORDIAN TEROZOIC 3A MESSINIAN LATE lupian 269 C3A 83.6 ROADIAN 272 850 7.2 SANTONIAN 4 KUNGURIAN C4 86.3 279 TONIAN CONIACIAN 280 4A Cisura- C4A TORTONIAN 90 89.8 1000 1000 PERMIAN ARTINSKIAN 10 5 TURONIAN lian C5 93.9 290 SAKMARIAN STENIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 296 SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 ASSELIAN 299 5A 100 100 300 GZHELIAN 1200 C5A 13.8 LATE 304 KASIMOVIAN 307 1250 MESOPRO- 15 LANGHIAN ECTASIAN 5B C5B ALBIAN MIDDLE MOSCOVIAN 16.0 TEROZOIC 5C C5C 110 VANIAN 315 PENNSYL- 1400 EARLY 5D C5D MIOCENE 113 320 BASHKIRIAN 323 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 1500 CALYMMIAN 6 C6 APTIAN LATE 20 120 331 6A C6A 20.4 EARLY 1600 M0r 126 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 MIDDLE VISEAN MISSIS- M3 BARREMIAN SIPPIAN STATHERIAN C6C 23.0 6C 130 M5 CRETACEOUS 131 347 1750 HAUTERIVIAN 7 C7 CARBONIFEROUS EARLY TOURNAISIAN 1800 M10 134 25 7A C7A 359 8 C8 CHATTIAN VALANGINIAN M12 360 140 M14 139 FAMENNIAN OROSIRIAN 9 C9 M16 28.1 M18 BERRIASIAN 2000 PROTEROZOIC 10 C10 LATE -

Absolute Velocity of North America During the Mesozoic from Paleomagnetic Data

Tectonophysics 377 (2003) 33–54 www.elsevier.com/locate/tecto Absolute velocity of North America during the Mesozoic from paleomagnetic data Myrl E. Beck Jr.*, Bernard A. Housen Department of Geology, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA 98225, USA Received 13 September 2002; received in revised form 29 April 2003; accepted 25 August 2003 Abstract We use paleomagnetic data to map Mesozoic absolute motion of North America, using paleomagnetic Euler poles (PEP). First, we address two important questions: (1) How much clockwise rotation has been experienced by crustal blocks within and adjacent to the Colorado Plateau? (2) Why is there disagreement between the apparent polar wander (APW) path constructed using poles from southwestern North America and the alternative path based on poles from eastern North America? Regarding (1), a 10.5j clockwise rotation of the Colorado Plateau about a pole located near 35jN, 102jW seems to fit the evidence best. Regarding (2), it appears that some rock units from the Appalachian region retain a hard overprint acquired during the mid- Cretaceous, when the geomagnetic field had constant normal polarity and APW was negligible. We found three well-defined small-circle APW tracks: 245–200 Ma (PEP at 39.2jN, 245.2jE, R = 81.1j, root mean square error (RMS) = 1.82j), 200–160 Ma (38.5jN, 270.1jE, R = 80.4j, RMS = 1.06j), 160 to f 125 Ma (45.1jN, 48.5jE, R = 60.7j, RMS = 1.84j). Intersections of these tracks (the ‘‘cusps’’ of Gordon et al. [Tectonics 3 (1984) 499]) are located at 59.6jN, 69.5jE (the 200 Ma or ‘‘J1’’ cusp) and 48.9jN, 144.0jE (the 160 Ma or ‘‘J2’’ cusp). -

International Chronostratigraphic Chart

INTERNATIONAL CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC CHART www.stratigraphy.org International Commission on Stratigraphy v 2014/02 numerical numerical numerical Eonothem numerical Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Erathem / Era System / Period GSSP GSSP age (Ma) GSSP GSSA EonothemErathem / Eon System / Era / Period EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) / Eon GSSP age (Ma) present ~ 145.0 358.9 ± 0.4 ~ 541.0 ±1.0 Holocene Ediacaran 0.0117 Tithonian Upper 152.1 ±0.9 Famennian ~ 635 0.126 Upper Kimmeridgian Neo- Cryogenian Middle 157.3 ±1.0 Upper proterozoic Pleistocene 0.781 372.2 ±1.6 850 Calabrian Oxfordian Tonian 1.80 163.5 ±1.0 Frasnian 1000 Callovian 166.1 ±1.2 Quaternary Gelasian 2.58 382.7 ±1.6 Stenian Bathonian 168.3 ±1.3 Piacenzian Middle Bajocian Givetian 1200 Pliocene 3.600 170.3 ±1.4 Middle 387.7 ±0.8 Meso- Zanclean Aalenian proterozoic Ectasian 5.333 174.1 ±1.0 Eifelian 1400 Messinian Jurassic 393.3 ±1.2 7.246 Toarcian Calymmian Tortonian 182.7 ±0.7 Emsian 1600 11.62 Pliensbachian Statherian Lower 407.6 ±2.6 Serravallian 13.82 190.8 ±1.0 Lower 1800 Miocene Pragian 410.8 ±2.8 Langhian Sinemurian Proterozoic Neogene 15.97 Orosirian 199.3 ±0.3 Lochkovian Paleo- Hettangian 2050 Burdigalian 201.3 ±0.2 419.2 ±3.2 proterozoic 20.44 Mesozoic Rhaetian Pridoli Rhyacian Aquitanian 423.0 ±2.3 23.03 ~ 208.5 Ludfordian 2300 Cenozoic Chattian Ludlow 425.6 ±0.9 Siderian 28.1 Gorstian Oligocene Upper Norian 427.4 ±0.5 2500 Rupelian Wenlock Homerian -

Paleogeographic Maps Earth History

History of the Earth Age AGE Eon Era Period Period Epoch Stage Paleogeographic Maps Earth History (Ma) Era (Ma) Holocene Neogene Quaternary* Pleistocene Calabrian/Gelasian Piacenzian 2.6 Cenozoic Pliocene Zanclean Paleogene Messinian 5.3 L Tortonian 100 Cretaceous Serravallian Miocene M Langhian E Burdigalian Jurassic Neogene Aquitanian 200 23 L Chattian Triassic Oligocene E Rupelian Permian 34 Early Neogene 300 L Priabonian Bartonian Carboniferous Cenozoic M Eocene Lutetian 400 Phanerozoic Devonian E Ypresian Silurian Paleogene L Thanetian 56 PaleozoicOrdovician Mesozoic Paleocene M Selandian 500 E Danian Cambrian 66 Maastrichtian Ediacaran 600 Campanian Late Santonian 700 Coniacian Turonian Cenomanian Late Cretaceous 100 800 Cryogenian Albian 900 Neoproterozoic Tonian Cretaceous Aptian Early 1000 Barremian Hauterivian Valanginian 1100 Stenian Berriasian 146 Tithonian Early Cretaceous 1200 Late Kimmeridgian Oxfordian 161 Callovian Mesozoic 1300 Ectasian Bathonian Middle Bajocian Aalenian 176 1400 Toarcian Jurassic Mesoproterozoic Early Pliensbachian 1500 Sinemurian Hettangian Calymmian 200 Rhaetian 1600 Proterozoic Norian Late 1700 Statherian Carnian 228 1800 Ladinian Late Triassic Triassic Middle Anisian 1900 245 Olenekian Orosirian Early Induan Changhsingian 251 2000 Lopingian Wuchiapingian 260 Capitanian Guadalupian Wordian/Roadian 2100 271 Kungurian Paleoproterozoic Rhyacian Artinskian 2200 Permian Cisuralian Sakmarian Middle Permian 2300 Asselian 299 Late Gzhelian Kasimovian 2400 Siderian Middle Moscovian Penn- sylvanian Early Bashkirian -

2009 Geologic Time Scale Cenozoic Mesozoic Paleozoic Precambrian Magnetic Magnetic Bdy

2009 GEOLOGIC TIME SCALE CENOZOIC MESOZOIC PALEOZOIC PRECAMBRIAN MAGNETIC MAGNETIC BDY. AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE POLARITY PICKS AGE PICKS AGE . N PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE PERIOD EPOCH AGE EON ERA PERIOD AGES (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) (Ma) HIST. HIST. ANOM. ANOM. (Ma) CHRON. CHRO HOLOCENE 65.5 1 C1 QUATER- 0.01 30 C30 542 CALABRIAN MAASTRICHTIAN NARY PLEISTOCENE 1.8 31 C31 251 2 C2 GELASIAN 70 CHANGHSINGIAN EDIACARAN 2.6 70.6 254 2A PIACENZIAN 32 C32 L 630 C2A 3.6 WUCHIAPINGIAN PLIOCENE 260 260 3 ZANCLEAN 33 CAMPANIAN CAPITANIAN 5 C3 5.3 266 750 NEOPRO- CRYOGENIAN 80 C33 M WORDIAN MESSINIAN LATE 268 TEROZOIC 3A C3A 83.5 ROADIAN 7.2 SANTONIAN 271 85.8 KUNGURIAN 850 4 276 C4 CONIACIAN 280 4A 89.3 ARTINSKIAN TONIAN C4A L TORTONIAN 90 284 TURONIAN PERMIAN 10 5 93.5 E 1000 1000 C5 SAKMARIAN 11.6 CENOMANIAN 297 99.6 ASSELIAN STENIAN SERRAVALLIAN 34 C34 299.0 5A 100 300 GZELIAN C5A 13.8 M KASIMOVIAN 304 1200 PENNSYL- 306 1250 15 5B LANGHIAN ALBIAN MOSCOVIAN MESOPRO- C5B VANIAN 312 ECTASIAN 5C 16.0 110 BASHKIRIAN TEROZOIC C5C 112 5D C5D MIOCENE 320 318 1400 5E C5E NEOGENE BURDIGALIAN SERPUKHOVIAN 326 6 C6 APTIAN 20 120 1500 CALYMMIAN E 20.4 6A C6A EARLY MISSIS- M0r 125 VISEAN 1600 6B C6B AQUITANIAN M1 340 SIPPIAN M3 BARREMIAN C6C 23.0 345 6C CRETACEOUS 130 M5 130 STATHERIAN CARBONIFEROUS TOURNAISIAN 7 C7 HAUTERIVIAN 1750 25 7A M10 C7A 136 359 8 C8 L CHATTIAN M12 VALANGINIAN 360 L 1800 140 M14 140 9 C9 M16 FAMENNIAN BERRIASIAN M18 PROTEROZOIC OROSIRIAN 10 C10 28.4 145.5 M20 2000 30 11 C11 TITHONIAN 374 PALEOPRO- 150 M22 2050 12 E RUPELIAN -

Marine Gastropods from the Pogibshi Formation (Alaska) and Their Paleobiogeographical Significance

Andean Geology 47 (3): 559-576. September, 2020 Andean Geology doi: 10.5027/andgeoV47n3-3278 www.andeangeology.cl Early Jurassic (middle Hettangian) marine gastropods from the Pogibshi Formation (Alaska) and their paleobiogeographical significance *Mariel Ferrari1, Robert B. Blodgett2, Montana S. Hodges3, Christopher L. Hodges3 1 Instituto Patagónico de Geología y Paleontología, IPGP (CCT CONICET-CENPAT), Boulevard Alte. Brown 2915, (9120) Puerto Madryn, Provincia de Chubut, Argentina. [email protected] 2 Blodgett and Associates, LLC, 2821 Kingfisher Drive, Anchorage, Alaska 99502, USA. [email protected] 3 California State University Sacramento, 6000 J Street, Sacramento, California 95819, USA. [email protected]; [email protected] * Corresponding author: [email protected] ABSTRACT. A middle Hettangian marine gastropod assemblage is reported from the Kenai Peninsula of south-central Alaska supplying new paleontological evidence of this group in Lower Jurassic rocks of North America. Pleurotomaria pogibshiensis sp. nov. is described from the middle Hettangian marine succession informally known as Pogibshi formation, being the first occurrence of the genus in the Kenai Peninsula and the oldest occurrence of the genus in present-day Alaska and North America. One species of the genus Lithotrochus, namely Lithotrochus humboldtii (von Buch), is also reported for the first time from the Kenai Peninsula. Lithotrochus has been considered as endemic to South America for a time range from the early Sinemurian -

Customising the Geological Timescale Applying the International Geological Timescale to Australia John Laurie, Daniel Mantle and Robert S Nicoll

ISSUE 92 Dec 2008 Customising the geological timescale Applying the international geological timescale to Australia John Laurie, Daniel Mantle and Robert S Nicoll A standardised and precise timescale is invaluable to geological Chronostratigraphic (relative- research and crucial to meaningful correlation at local, regional time) units, such as rock and global scales for both researchers and industry. Modelling of formations, biozones (or all the petroleum system plays and ore-body generation, for example, both rocks characterised by a particular depend on accurate timescales to be usefully interpreted. fossil), and magnetostratigraphy, The geological timescale is one of the major achievements of are calibrated against a geoscience. It has been developed by geologists over the past two chronometric scale (an absolute centuries to describe and understand the history of the earth. age in years) to build the timescale. Absolute ages (years GTS 82 Ex 88 SEPM 95 Age Holmes Holmes Harland et Haq et al. Gradstein GTS 2004 before present) are usually (Ma) 1937 1960 al. 1982 1987 et al. 1995 measured using radiometric 108 110 dating techniques and in the Cenozoic and Mesozoic can be 115 calibrated against high resolution 120 c orbital forcing events (that is, 125 astronomical cycles). Modern 130 131 Jurassi techniques and instruments are 135 Tithonian 135 delivering increasingly accurate 140 Kimmeridgian ages (with precision down to ± 144 144.2 145.5 145 0.1 per cent), whilst biozonation 145 Tithonian Tithonian Oxfordian Tithonian 150 schemes are continually refined Kimmeridgian c Kimmeridgian Kimmeridgian 155 Callovian Oxfordian and standardised on a global Oxfordian Oxfordian 160 Bathonian basis. As such, constant updating Jurassi Callovian Callovian 165 of the geological timescale is Callovian Bathonian Bathonian Bajocian 170 Bajocian required and it will always remain Bathonian Bajocian Aalenian a flexible, on-going project 175 Aalenian Bajocian Aalenian (see figure 1). -

INTERNATIONAL CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC CHART International Commission on Stratigraphy V 2020/03

INTERNATIONAL CHRONOSTRATIGRAPHIC CHART www.stratigraphy.org International Commission on Stratigraphy v 2020/03 numerical numerical numerical numerical Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age Series / Epoch Stage / Age GSSP GSSP GSSP GSSP EonothemErathem / Eon System / Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) EonothemErathem / Eon System/ Era / Period age (Ma) Eonothem / EonErathem / Era System / Period GSSA age (Ma) present ~ 145.0 358.9 ±0.4 541.0 ±1.0 U/L Meghalayan 0.0042 Holocene M Northgrippian 0.0082 Tithonian Ediacaran L/E Greenlandian 0.0117 152.1 ±0.9 ~ 635 U/L Upper Famennian Neo- 0.129 Upper Kimmeridgian Cryogenian M Chibanian 157.3 ±1.0 Upper proterozoic ~ 720 0.774 372.2 ±1.6 Pleistocene Calabrian Oxfordian Tonian 1.80 163.5 ±1.0 Frasnian 1000 L/E Callovian Quaternary 166.1 ±1.2 Gelasian 2.58 382.7 ±1.6 Stenian Bathonian 168.3 ±1.3 Piacenzian Middle Bajocian Givetian 1200 Pliocene 3.600 170.3 ±1.4 387.7 ±0.8 Meso- Zanclean Aalenian Middle proterozoic Ectasian 5.333 174.1 ±1.0 Eifelian 1400 Messinian Jurassic 393.3 ±1.2 Calymmian 7.246 Toarcian Devonian Tortonian 182.7 ±0.7 Emsian 1600 11.63 Pliensbachian Statherian Lower 407.6 ±2.6 Serravallian 13.82 190.8 ±1.0 Lower 1800 Miocene Pragian 410.8 ±2.8 Proterozoic Neogene Sinemurian Langhian 15.97 Orosirian 199.3 ±0.3 Lochkovian Paleo- Burdigalian Hettangian proterozoic 2050 20.44 201.3 ±0.2 419.2 ±3.2 Rhyacian Aquitanian Rhaetian Pridoli 23.03 ~ 208.5 423.0 ±2.3 2300 Ludfordian 425.6 ±0.9 Siderian Mesozoic Cenozoic Chattian Ludlow -

Paleontology of the Bears Ears National Monument

Paleontology of Bears Ears National Monument (Utah, USA): history of exploration, study, and designation 1,2 3 4 5 Jessica Uglesich , Robert J. Gay *, M. Allison Stegner , Adam K. Huttenlocker , Randall B. Irmis6 1 Friends of Cedar Mesa, Bluff, Utah 84512 U.S.A. 2 University of Texas at San Antonio, Department of Geosciences, San Antonio, Texas 78249 U.S.A. 3 Colorado Canyons Association, Grand Junction, Colorado 81501 U.S.A. 4 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Wisconsin-Madison, Madison, Wisconsin, 53706 U.S.A. 5 University of Southern California, Los Angeles, California 90007 U.S.A. 6 Natural History Museum of Utah and Department of Geology & Geophysics, University of Utah, 301 Wakara Way, Salt Lake City, Utah 84108-1214 U.S.A. *Corresponding author: [email protected] or [email protected] Submitted September 2018 PeerJ Preprints | https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.3442v2 | CC BY 4.0 Open Access | rec: 23 Sep 2018, publ: 23 Sep 2018 ABSTRACT Bears Ears National Monument (BENM) is a new, landscape-scale national monument jointly administered by the Bureau of Land Management and the Forest Service in southeastern Utah as part of the National Conservation Lands system. As initially designated in 2016, BENM encompassed 1.3 million acres of land with exceptionally fossiliferous rock units. Subsequently, in December 2017, presidential action reduced BENM to two smaller management units (Indian Creek and Shash Jáá). Although the paleontological resources of BENM are extensive and abundant, they have historically been under-studied. Here, we summarize prior paleontological work within the original BENM boundaries in order to provide a complete picture of the paleontological resources, and synthesize the data which were used to support paleontological resource protection.