Glossary 1 Terms Used in Graphic Design and Printing

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Introducing Opentype Ab

UBS AG ab Postfach CH-8098 Zürich Tel. +41-44-234 11 11 Brand Management Visual Identity Stephanie Teige FG09 G5R4-Z8S Tel. +41-1-234 59 09 Introducing OpenType Fax +41-1-234 36 41 [email protected] July 2005 www.ubs.com OpenType is a new font format developed collaboratively by Adobe and Microsoft. OpenType enhances the TrueType and PostScript technologies and extends their capabilities. Most fonts today are released in the OpenType format, now considered the industry standard. The resulting new generation of UBSHeadline and Frutiger fonts offers improved typographic and layout features. 1. What is OpenType? Frutiger is not always Frutiger Due to the wide variety of Frutiger styles available world- A single font format wide, be sure to install and use only the client-specific UBS OpenType provides a single universally acceptable font licensed version of this font. Do not use any other versions format that can be used on any major operating system of Frutiger to create UBS media. and in any application. Using the client-specific UBS Frutiger guarantees access to Macintosh Windows UBS-relevant cuts. It also prevents changes to kerning and line-break in comparison to random Frutiger styles. UBSHeadline, Frutiger UBSHeadline, Frutiger (PostScript) (TrueType) Linotype Frutiger UBS Frutiger Frutiger LT 45 Light Frutiger 45 Light Macintosh and Frutiger LT 46 Light Italic Frutiger 45 Light Italic Windows Frutiger LT 55 Roman Frutiger 55 Roman Frutiger LT 56 Italic Frutiger 55 Roman Italic UBSHeadline, Frutiger Frutiger LT 65 Bold Frutiger 45 Light Bold (OpenType) Frutiger LT 75 Black Frutiger 55 Roman Bold Frutiger LT 47 Light Condensed Frutiger 47 Light CN Unicode OpenType supports Unicode, which allows much larger Comparison of common Linotype Frutiger versus UBS client- character sets – more than 65,000 glyphs per font in many specific Frutiger. -

INTRODUCTORY CONCEPTS Desktop Publishing Terms Overview

INTRODUCTORY CONCEPTS Desktop Publishing Terms Overview GOAL: Produce a reference guide demonstrating desktop publishing (DTP) terms. Crosswalk Measurable Learner to Show-Me Instructional Activities Assessment Objectives Standards Define terms related to desktop CA1, 2.1 Accurately define at least 15 Use the Desktop Publishing Terms publishing. A1 alphabetized desktop publishing terms to assessment to evaluate the definitions Import text files and word CA1, 2.1 be used as a reference guide. Students provided of each term. Also evaluate processing documents into will select terms from a listing generated the ability to demonstrate the specified publications. C2 by the instructor or other provided terms; the use of appropriate desktop Set margins. B1 CA1, 2.1 source(s). The terms will be displayed publishing layout and design with text, Create columns. B2 CA1, 2.1 in an appropriate easy-to-read format graphics, columns, and gutters Set guttering. B3 CA1, 2.1 according to DTP concepts. Each effectively manipulated; the use of Create an effective focal point. CA1, 2.1 definition is to demonstrate the term appropriately selected graphics to B6 used, e.g., drop cap will begin with a represent definitions; proper font Utilize pasteboard. B7 CA1, 2.1 drop cap. Effective DTP layout and selection and sizing; and the use of the Import graphics from various CA3, 2.7 design are to be used in margins, focal number of terms and graphics specified. sources (e.g., software-specific point, columns and gutters, etc. A The ability to provide an error-free library, other applications, minimum of 5 related graphics are to be document will also be assessed. -

Desktop Publishing: Page Layout Design Introduction

M2: Desktop Publishing Objectives Desktop Publishing: Page Layout Design Introduction Discrete Documents Course: Master of Arts Softwares Course Name: Computer and Information Technology Course Code: HIND4014 Basic Tools Semester: II File Extension Session: 2019-20 Desktop Publishing Software: Adobe Pagemaker Mr. Joynath Mishra Introduction Assistant Professor (Guest) Importance Computer Science and Information Technology Coverpage Creation Mahatma Gandhi Central University Poster Creation Motihari, Bihar Exercise References April 6, 2020 . Outline M2: Desktop Publishing 1 Objectives Objectives 2 Introduction Introduction Discrete 3 Discrete Documents Documents Softwares 4 Softwares Basic Tools File Extension 5 Basic Tools Desktop Publishing Software: Adobe 6 File Extension Pagemaker Introduction Importance 7 Desktop Publishing Software: Adobe Pagemaker Introduction Coverpage Creation Importance Poster Creation Coverpage Creation Poster Creation Exercise References 8 Exercise 9 References . Objectives M2: Desktop Publishing Objectives Introduction Discrete Documents Softwares Objectives Basic Tools Study on Context of Desktop Publishing File Extension Importance of Desktop Publishing Desktop Publishing Study on creation of title/cover page, advertisement Software: Adobe Pagemaker Introduction Importance Coverpage Creation Poster Creation Exercise References . Introduction M2: Desktop Publishing Introduction Objectives Desktop publishing is a process to produce organized soft copy format of text and graphics in a single page/platform. -

Desktop Publishing

ORDINANCE FOR DESKTOP PUBLISHING Offered by KUMAUN UNIVERSITY, NAINITAL 2015-2016 By Deen Dayal Upadhyay Kaushal Kendra S.B.S. Government P.G. College, Rudrapur (U.S. Nagar) Uttarakhand 1 B. Voc (Desktop Publishing) DESCRIPTION & OBJECTIVES COURSE DESKTOP PUBLISHING : 1. DESCRIPTION This course introduces students to the principles of design applicable to publications created using desktop publishing software and computer technology. Special attention is given to design principles, typography, and layout and production techniques. This class focuses on gaining professional-level skills and knowledge. In this course, the students will discover how to use the essential building blocks of design type, art and line in new and creative ways, learn clever ways to locate and use resources such as graphics and scanned art, learn to think about audience and medium and how those affect the way you craft your message and also be learning to use new technical tools to create those effective messages. In the end, the students will have a more critical eye for design and production techniques, be able to "talk the talk of desktop publishing" and will know how to design and create attractive publications. In short, the students have valuable skills that you can use in social or professional settings, from creating a newsletter for an organization. This class will follow a step-by-step process that gives you usable amounts of information in "byte-size" pieces; each assignment builds on what you have already learned. Teaching methods combine presentation, examples and discussion with considerable hands-on production and personal feedback. 2. OBJECTIVES: The principal goal for this class is to develop specific skills, competencies and points of view needed by professionals who use computer hardware and software in the hands-on production of publications. -

Unit 1 Intro to Desktop Publishing

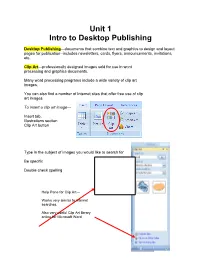

Unit 1 Intro to Desktop Publishing Desktop Publishing—documents that combine text and graphics to design and layout pages for publication--includes newsletters, cards, flyers, announcements, invitations, etc. Clip Art—professionally designed images sold for use in word processing and graphics documents. Many word processing programs include a wide variety of clip art images. You can also find a number of Internet sites that offer free use of clip art images. To insert a clip art image— Insert tab, Illustrations section Clip Art button Type in the subject of images you would like to search for Be specific Double check spelling Help Pane for Clip Art— Works very similar to Internet searches. Also very useful Clip Art library online for Microsoft Word Once search is complete, you will get a menu of pictures to choose from. Click on the drop down arrow next to the picture. Choose Insert from the menu. Text Wrapping—change the way text is placed around a selected graphic or other object. Make sure image is active (handles around picture)— Use Picture Tools tab and Format tab Arrange section Text Wrapping button Text Wrapping Choices In Line with Text—words are placed on a line above and below the picture Square—moves the words around the image leaving a square area containing the image Tight—moves the words around the image and follows the contours of the image. Behind Text—allows the words to show in front of (or float over) the picture. In Front of Text—allows you to “float” the graphic over the text and place it wherever you wish (the text is covered by the graphic). -

Desktop Publishing 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore

B.Com 1st Year (Plain) Subject- Desktop Publishing SYLLABUS Class – B.Com. I Year Subject – Desktop Publishing UNIT – I Importance and Advantages of DTP, DTP Software and Hardware, Commercial DTP Packages, Page Layout programs, Introduction to Word Processing, Commercial DTP Packages, Difference between DTP Software and word Processing. UNIT – II Types of Graphics, Uses of Computer Graphics Introduction to Graphics Programs, Font and Typeface, Types of Fonts, Creation of Fonts (Photographer), Anatomy of Typefaces, Printers, Types of Printers used in DTP, Plotter, Scanner. UNIT – III History and Versions of PageMaker, Creating a New Page, Document Setup Dialog Box, Paper size, Page Orientation, Margins, Different Methods of Placing text and graphics in a document, master Page, Story Editor, Formatting of Text, Indent, Leading, Hyphenation, Spelling Check, Creating Index, Text Wrap, Position (Superscript/Subscript), Control Palette. UNIT – IV History of Multimedia Elements, Text, Images, Sound, Animation and Video, Text, concept of Plain Text and Formatted Text, RTF& HTML Text, Image, Importance of Graphics in Multimedia, Image Capturing Methods, Scanner, Digital Camera, Sound0 Sound and its effect in Multimedia, Analog and Digital sound, Animation, Basics, Principles and use of Animation, video, Basics of Video, Analog and Digital Video. UNIT – V Features Of Multimedia, Overview of Multimedia, Multimedia Software Tools, Multimedia Authoring- Production and Presentation, Graphics File Formats, MIDI-Overviews, Concepts, Structure of MIDI, MIDI Devices, MIDI Messages. 45, Anurag Nagar, Behind Press Complex, Indore (M.P.) Ph.: 4262100, www.rccmindore.com 1 B.Com 1st Year (Plain) Subject- Desktop Publishing UNIT I 1.1 Introduction to Desktop Publishing Desktop Publishing (DTP) is the creation of electronic forms of information documents using page layout skills on a personal computer primarily for print. -

The Desktop Toolbox: Software for Document Creation

The Desktop Toolbox: Software for Document Creation The term desktop publishing is generally agreed to have been coined in 1985 by Paul Brainerd, founder of Aldus Corporation, following the development of Aldus PageMaker (later purchased by Adobe). In its original usage, desktop publishing meant the ability of one person to use a computer to perform what had previously been many separate functions – design, typesetting, pasteup and preparation of camera ready artwork. Thus desktop publishing combined several disciplines (graphic design, writing, editing, typography and page composition) into one. Word processing, a term invented by IBM in the 1960s, predates desktop publishing by more than a decade. Early word processors were typewriters with some form of electronic editing and correction capability; later machines incorporated CRT screens (as exemplified by the Wang word processor). Eventually, dedicated word processing equipment was replaced by software applications running on personal computers. The most popular word processing program in use today is Microsoft Word. The distinction is blurred Desktop publishing versus word processing Today the distinction between high-end word processors and low-end desktop publishing software is blurred. Lower-cost Although some may use the terms interchangeably, there is a alternatives to established desktop publishing programs like difference between word processing and desktop publishing. Quark XPress and Adobe InDesign are now available, while word Broadly speaking, word processing consists of assigning style processing software like Word and WordPerfect are adding page characteristics to the page (margins, line length, indents, space layout features. And two programs – Microsoft Publisher and between paragraphs, page numbers, etc.) and the text itself Adobe PageMaker – are positioned between the two groups. -

Entrep-Based DESKTOP PUBLISHING

Information & Communications Technology (ICT) DESKTOP PUBLISHING INTRODUCTION Information and Communication Technology(ICT) is one of the components of Technology and Livelihood Education(TLE). It offers a lot of skills appropriate for the jobs offered by the different companies nowadays. Desktop Publishing(DTP) is the use of the computer and software to create visual display of ideas and information. This module is divided into three lessons namely: Desktop Publishing and the Microsoft Software, Common Tasks in Publisher and Creating A New Publication. These lessons will help you produce creative and innovative business cards, letterheads, newsletters, booklets, manuals, brochures, advertisements, business forms, reports, magazines, catalogues, programs, flyers, posters and invitations. Moreover, you will be trained to create pages using imported text and graphics, modify text and graphics within a page and link pages and text boxes. You will identify and choose appropriate fonts for your project, select, import, and manipulate graphics and format pages appropriate for presentation. MS Publisher will be the specific program/software in creating your publication. Hence, you may also use other software, such as: Corel Draw, Adobe Page Maker and Adobe InDesign to help you in creating your design. So, explore and experience the K to 12 TLE modules and be a step closer to becoming a successful graphic designer. *** ICT- Desktop Publishing Page 2 OBJECTIVES At the end of this module, you are expected to: explain the basic concept and features of Desktop Publishing(DTP), use Desktop Publishing Softwares such as Microsoft MS Publisher, Indesign, Adobe Page Maker, Corel Draw, etc. create designs using Desktop Publishing PRE ASSESSMENT To test your prior knowledge on Desktop Publishing, answer the Pre Assessment below. -

COURSE TITLE Desktop Publishing

COURSE TITLE Desktop Publishing LENGTH One Semester Grades 10 – 12 DEPARTMENT Business Education Barbara O’Donnell, Supervisor SCHOOL Rutherford High School DATE Spring 2017 DESKTOP PUBLISHING I. Introduction/Overview/Philosophy Desktop Publishing is a term used to describe an exciting development in computer applications that combines a computer, software, a scanner, a digital camera, the Internet, a laser printer, and a color printer into a stand- alone publishing system. This course will begin with a brief explanation of the publishing and printing process—the terminology, the history, the jobs, the hardware and the software. Desktop Publishing will be introduced as an application of computer technology to an old, established process. Elements of attractive page layout, color and design will be stressed. Desktop Publishing software will be used to develop a set of publishing projects that begin with simple drawings, announcements and magazine covers and increase in complexity to multi-page documents such as menus, newsletters, tri-fold brochures, a business proposal and a school newspaper. The course is designed for the student who is interested in pursuing any career in the publishing, business or education fields, since most documents such as newsletters, brochures, invitations, and announcements are created and produced in-house, rather than by an outside print shop. II. Objectives Course Outline: A. Introduction to Desktop Publishing 1. Discuss the publishing and printing process a. Plan b. Design page c. Create content d. Page layout e. Print 2. Discuss history of Desktop Publishing B. Desktop Publishing Basics 1. Define advantages and disadvantages of using Desktop Publishing software 2. Discuss applications of Desktop Publishing 3. -

Desktop Publishing II

Desktop Publishing II EXAM INFORMATION DESCRIPTION Exam Number All standards in Desktop Publishing II build upon concepts and 249 principles in Desktop Publishing I. DTP II must be taught using Items current professional software. Word and Publisher are not considered professional software applications by industry. 41 Points EXAM BLUEPRINT 42 Prerequisites STANDARD PERCENTAGE OF EXAM DESKTOP PUBLISHING I 1- Planning 19% 2- Typography & Design Principles 33% Recommended Course 3- Color 19% Length 4- Images 21% ONE SEMESTER 5- Image & Text 8% National Career Cluster ARTS, A/V TECHNOLOGY & COMMUNICATION BUSINESS MANAGEMENT & ADMINISTRATION INFORMATION TECHNOLOGY MARKETING Performance Standards INCLUDED (OPTIONAL) Certificate Available YES www.precisionexams.com Desktop Publishing II 249.2021 STANDARD 1 Students will understand the process of planning a document. Objective 1 Students should understand the importance of preplanning a document in terms of audience, purpose, timeline, budget, page arrangement, and production method. Objective 2 Students will use guides, grids, and columns to set up their documents as a way to create consistency and unity. Objective 3 Students will understand that master pages are used to create consistency and increase productivity. Objective 4 Students will understand that headers and footers contain recurring information and that they are used to help organize a publication. Objective 5 Students will understand that slug space is a space outside the printed area in which you can place instructions that stay with our document. STANDARD 2 Students will expand on typography and design principles learned in DTP 1. Objective 1 Students will develop an understanding of basic desktop publishing terminology (see teacher helps vocabulary list). -

Basics of Desktop Publishing. Teacher Edition. INSTITUTION Mid-America Vocational Curriculum Consortium, Stillwatar, Okla

DOCUMENT RESUME ED 327 658 CE 056 668 AUTHOR Beeby, Ellen TITLE Basics of Desktop Publishing. Teacher Edition. INSTITUTION Mid-America Vocational Curriculum Consortium, Stillwatar, Okla. PUB DATE 91 NOTE 331p. AVAILABLE FROMMid-Amarica Vocational Curriculum Consortium, 1500 West Sevc,nth Avenue, Stillw.ter, OK 74074 (order no. 601601: $23.50). PUB TYPE Guides Classroom Use - Guides (For Teachers) (052) EDRS PRICE MF01 Plus Postage. PC Not Available from EDRS. DESCRIPTORS Behavioral Objectives; *Computer Oriented Programs; *Computer Software; *Desktop Publishing; Electronic Publishing; *Layout (Publications); Learning Activities; Lesson Plans; Microcomputers; Postsecondary Education; Printing; Publications; Secondary Education; Teaching Methods; Test Items; Units of Study ABSTRACT This color-coded teacher's guide contains curriculum materials designed to give students an awareness of various desktop publishing techniques before they determine their computer hardware and software needs. The guide contains six units, each of which includes some or all of the following basic components: objective sheet, suggested activities for the teacher, instructor supplements, transparency masters, information sheet, assignment sheets, assignment sheet answers, job sheets, practical tests, written test, and answers to written test. Units cover the following topics: introduction to desktop publishing; desktop publishing systems; software; type selection; document design; and layout. All of the units focus on measurable and observable learning outcomes. They are designed for use in more than one lesson or class period of instruction. (KC) *****************:*****..*******k*************************************** Reproductions supplied by EDRS are the best that can be made froin the original document. *********************************************************************** Basics of Desktop Publishing Written by Ellen Beeby Project Coordinated by Sue Buck Developed by The Mid-America Vocational Curriculum Consortium, Inc. -

Layout a Bid

Layout a bid Adapted from IACURH Award Resource Guide Layout Overview What is bid layout? The layout of a bid is the organization of information on each page and throughout the bid. Oftentimes, this includes different outlets for displaying text and information, graphical depictions of thematic elements and more. Layout Methods Paragraphs Bulleted Lists Text Boxes Graphics Pictures Backgrounds Why does layout matter? The layout of a bid can be just as important as who or what the bid is written about. The most deserving subject could be buried by a bid with poor layout. Information If information is hard to find or comprehend in depth and at a glance, the bid becomes less effective. This can be taken care of with effective layout methods (bulleted lists, text boxes, etc.). Theme The layout of a bid is the easiest way to incorporate thematic elements (images, wording, attitude, etc.). This will help you better expose the audience to the theme and, as a result, aid them in developing a better understanding of your nominee. Fun & Readability It’s simple; a well laid-out bid is just easier and more fun to read and makes the bidding process exciting. Without being able to read the text, which of the following would you prefer to read? Layout Basics Once you’ve selected your layout software program, it’s time to start thinking about the layout of your bid. The following suggestions will help you to set the foundation for your bid layout: Select Layout the List Topics Storyboard Review Theme Bid 1. Select Theme First, select the theme of your bid if you will be using one.