Uganda Human Development Report 2015

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ending CHILD MARRIAGE and TEENAGE PREGNANCY in Uganda

ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA 1 A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA Final Report - December 2015 ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS The United Nations Children Fund (UNICEF) gratefully acknowledges the valuable contribution of many individuals whose time, expertise and ideas made this research a success. Gratitude is extended to the Research Team Lead by Dr. Florence Kyoheirwe Muhanguzi with support from Prof. Grace Bantebya Kyomuhendo and all the Research Assistants for the 10 districts for their valuable support to the research process. Lastly, UNICEF would like to acknowledge the invaluable input of all the study respondents; women, men, girls and boys and the Key Informants at national and sub national level who provided insightful information without whom the study would not have been accomplished. I ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA A FORMATIVE RESEARCH TO GUIDE THE IMPLEMENTATION OF THE NATIONAL STRATEGY ON ENDING CHILD MARRIAGE AND TEENAGE PREGNANCY IN UGANDA CONTENTS ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS ..................................................................................I -

OFFICE of the PRIME MINISTER MINISTRY for KARAMOJA AFFAIRS Karamoja Integrated Development Plan 2 (KIDP 2) FOREWORD

OFFICE OF THE PRIME MINISTER MINISTRY FOR KARAMOJA AFFAIRS Karamoja Integrated Development Plan 2 (KIDP 2) 2015 – 2020 FOREWORD The Karamoja Integrated Development Plan (KIDP 2) is a deliberate strategy by Government to enhance coordination efforts in addressing development gaps after peace was restored in KIDP 2 Karamoja. This will be achieved through the intensification of development interventions in the sub-region; specifically, in the provision of potable water and water for production, enhancing the production of sufficient food for households and incomes, improving access to quality health and education services, improving livestock production and productivity, markets, promoting and augmenting the mineral sector, infrastructure development, and harnessing the tourism potential in the sub-region. In the past Karamoja was too insecure for development interventions to take place, however the successful voluntary disarmament programme enforced by Government is gradually changing the region and has drastically improved security. Peace is now being enjoyed in all parts of Karamoja making it a better place to live in and develop. The improved security is a result of the concerted efforts of my office in collaboration with security forces, especially the Ministry of Defence, Ministry of Internal Affairs, Ministry of Justice and Constitutional Affairs. This has been in collaboration and partnership with development partners and civil society actors who successfully engaged in the mobilisation and sensitization of the communities. Most of the people in Karamoja are now in favour of peace building, food production, and improved cattle keeping among other interventions. Indeed, the conflict analysis pattern in the region has changed considerably for the better. -

Doctors with Africa CUAMM Annual Report 2015

Doctors with Africa CUAMM Annual Report 2015 Doctors with Africa CUAMM Annual Report 2015 Design Heads Collective Layout Heads Collective Publistampa Arti grafiche Photography Archivio CUAMM Nicola Antolino Luigi Baldelli Nicola Berti Maria Nannini Monika Bulaj Gigi Donelli Reed Young Drafting Andrea Atzori Stefano Bassanese Andrea Borgato Chiara Di Benedetto Chiara Cavagna Andrea Iannetti Fabio Manenti Bettina Simoncini Jacopo Soranzo Anna Talami Samuele Zamuner Mario Zangrando Printed by Grafica Veneta via Malcanton, 1 Trebaseleghe (PD) Acknowledgement Grafica Veneta for printing the Report free of charge Printed in August 2016 Supplement no.2 to the magazine èAfrica n.5/2016 - authorization of Court of Padova. Press register no. 1633 dated 19.01.1999 CONTENTS 4 Introduction 99 Report on Italy 4 Our mission continues 100 Communication 6 Sustainable Development Goals 104 Community relations 7 Strategic plan 2008-2015 and fundraising 8 The position in 10 points 107 Education 9 Mission and awareness building 10 Organization 109 Student College 110 Historical archive 13 Report on Africa 111 Financial statements 14 Angola 22 Ethiopia 30 Mozambique 38 Sierra Leone 46 South Sudan 58 Tanzania 68 Uganda 76 Focus on hospitals 86 Focus on Mothers and children first 94 Human resources management 98 Partnership p. 04 Doctors with Africa CUAMM Annual Report 2015 OUR MISSION CONTINUES Rev. Dante Carraro, As usual, looking back at what throughout the year, which often tested director of Doctors with Africa happened during the previous year is our operators’ endurance and CUAMM like trying to “connect the dots”, finding commitment to the limit. Despite the the connection between moments and difficulties we kept finding new situations we experienced directly, as solutions, such as a network of mobile individuals, communities and entire phones and a 24-hour ambulance Countries. -

Unbs Upgrades Fuel Calibration Rig

UNBS UPGRADES FUEL CALIBRATION RIG PLUS: • UNBS wins Best Web Interface Award • UNBS’ New State of the Art Lab • Full List of UNBS Certified Products UNBS - Standards House Bweyogerere Industrial Park, Plot 2 - 12, Kyaliwajala road, P.O Box 6329 Kampala, Uganda Tel: +256 417 333 250 +256 312 262 688/9 Fax: +256 414 286 123 Website: www.unbs.go.ug Emial: [email protected] Toll Free Hotline: 0800133133 PUBLISHER The Quality Chronicles is a Quarterly publication produced for the Uganda National Bureau of Standards by: EAST AFRICAN MEDIA CONSULT Serena Hotel International Conference Centre Suite 152, P.O.Box 71919, Kampala Telephone: 256-41-4341725/6 Facsimile:256-41-4341726 Mob: 0772 593939 E-mail: [email protected] Editorial www.eastafricanmediaconsult.co.ug Uganda National Bureau of Standards MANAGING EDITOR continues to register success as one of the Julius Edwin Mirembe 0772 593939 leading government agencies both in service Contents delivery and non-tax revenue collection. In its EDITOR annual year performance report for 2018/2019, Jovia Kaganda • EXECUTIVE DIRECTOR’S PREFACE 041-4341725/6 the Bureau undertook Product Certification and UNBS Registers Exponential Growth in SME Registration 4 Management Systems Certification to improve STAFF WRITERS the quality of locally manufactured products so Julius Edwin Mirembe • FEATURE: Timothy Kyamulesire that more Ugandan goods are able to access Ssemutooke Joseph UNBS Set To Open Ultra Modern regional and international markets. This has Akena Joel Food Safety Laboratories 8 translated in increased growth. East African Media Consult • LEAD STORY Exports to the East African region grew by DESIGN AND LAYOUT Unbs Upgrades Calibration Rig To 51.8 percent from US$ 89.40 million in May Allan Brian Mukwana State Of The Art 12 East African Media Consult 2016 to US$ 135.74 million in May 2017. -

REPUBLIC of UGANDA Public Disclosure Authorized UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY

E1879 VOL.3 REPUBLIC OF UGANDA Public Disclosure Authorized UGANDA NATIONAL ROADS AUTHORITY FINAL DETAILED ENGINEERING Public Disclosure Authorized DESIGN REPORT CONSULTANCY SERVICES FOR DETAILED ENGINEERING DESIGN FOR UPGRADING TO PAVED (BITUMEN) STANDARD OF VURRA-ARUA-KOBOKO-ORABA ROAD Public Disclosure Authorized VOL IV - ENVIRONMENTAL AND SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT Public Disclosure Authorized The Executive Director Uganda National Roads Authority (UNRA) Plot 11 Yusuf Lule Road P.O.Box AN 7917 P.O.Box 28487 Accra-North Kampala, Uganda Ghana Feasibility Study and Detailed Design ofVurra-Arua-Koboko-Road Environmental Social Impact Assessment Final Detailed Engineering Design Report TABLE OF CONTENTS o EXECUTIVE SUMMARY .............................................................................................................. 0-1 1 INTRODUCTION ............................................................................................................................ 1-1 1.1 BACKGROUND OF THE PROJECT ROAD........................................................................................ I-I 1.3 NEED FOR AN ENVIRONMENTAL SOCIAL IMPACT ASSESSMENT STUDy ...................................... 1-3 1.4 OBJECTIVES OF THE ESIA STUDY ............................................................................................... 1-3 2 APPROACH AND METHODOLOGY .......................................................................................... 2-1 2.1 INITIAL MEETINGS WITH NEMA AND UNRA............................................................................ -

Killing the Goose That Lays the Golden Egg

KILLING THE GOOSE THAT LAYS THE GOLDEN EGG An Analysis of Budget Allocations and Revenue from the Environment and Natural Resource Sector in Karamoja Region Caroline Adoch Eugene Gerald Ssemakula ACODE Policy Research Series No.47, 2011 KILLING THE GOOSE THAT LAYS THE GOLDEN EGG An Analysis of Budget Allocations and Revenue from the Environment and Natural Resource Sector in Karamoja Region Caroline Adoch Eugene Gerald Ssemakula ACODE Policy Research Series No.47, 2011 Published by ACODE P. O. Box 29836, Kampala Email: [email protected]; [email protected] Website: http://www.acode-u.org Citation: Adoch, C., and Ssemakula, E., (2011). Killing the Goose that Lays the Golden Egg: An Analysis of Budget Allocations and Revenue from the Environment and Natural Resource Sector in Karamoja Region. ACODE Policy Research Series, No. 47, 2011. Kampala. © ACODE 2011 All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise without the prior written permission of the publisher. ACODE policy work is supported by generous donations and grants from bilateral donors and charitable foundations. The reproduction or use of this publication for academic or charitable purposes or for purposes of informing public policy is excluded from this restriction. ISBN 978997007077 Contents LIST OF FIGURES ................................................................................................. v LIST OF TABLES .................................................................................................. -

Mapping Uganda's Social Impact Investment Landscape

MAPPING UGANDA’S SOCIAL IMPACT INVESTMENT LANDSCAPE Joseph Kibombo Balikuddembe | Josephine Kaleebi This research is produced as part of the Platform for Uganda Green Growth (PLUG) research series KONRAD ADENAUER STIFTUNG UGANDA ACTADE Plot. 51A Prince Charles Drive, Kololo Plot 2, Agape Close | Ntinda, P.O. Box 647, Kampala/Uganda Kigoowa on Kiwatule Road T: +256-393-262011/2 P.O.BOX, 16452, Kampala Uganda www.kas.de/Uganda T: +256 414 664 616 www. actade.org Mapping SII in Uganda – Study Report November 2019 i DISCLAIMER Copyright ©KAS2020. Process maps, project plans, investigation results, opinions and supporting documentation to this document contain proprietary confidential information some or all of which may be legally privileged and/or subject to the provisions of privacy legislation. It is intended solely for the addressee. If you are not the intended recipient, you must not read, use, disclose, copy, print or disseminate the information contained within this document. Any views expressed are those of the authors. The electronic version of this document has been scanned for viruses and all reasonable precautions have been taken to ensure that no viruses are present. The authors do not accept responsibility for any loss or damage arising from the use of this document. Please notify the authors immediately by email if this document has been wrongly addressed or delivered. In giving these opinions, the authors do not accept or assume responsibility for any other purpose or to any other person to whom this report is shown or into whose hands it may come save where expressly agreed by the prior written consent of the author This document has been prepared solely for the KAS and ACTADE. -

2017 Statistical Abstract – Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development

THE REPUBLIC OF UGANDA MINISTRY OF ENERGY AND MINERAL DEVELOPMENT 2017 STATISTICAL ABSTRACT 2017 Statistical Abstract – Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development i FOREWORD The Energy and Mineral Development Statistics Abstract 2017 is the eighth of its kind to be produced by the Ministry. It consolidates all the Ministry’s statistical data produced during the calendar year 2017 and also contains data dating five years back for comparison purposes. The data produced in this Abstract provides progress of the Ministry’s contribution towards the attainment of the commitments in the National Development Plan II and the Ministry’s Sector Development Plan FY2015/16 – 2019/20. The Ministry’s Statistical Abstract is a vital document for dissemination of statistics on Energy, Minerals and Petroleum from all key sector players. It provides a vital source of evidence to inform policy formulation and further strengthens and ensures the impartiality, credibility of data/information collected. The Ministry is grateful to all its stakeholders most especially the data producers for their continued support and active participation in the compilation of this Abstract. I wish also to thank the Energy and Mineral Development Statistics Committee for the dedicated effort in compilation of this document. The Ministry welcomes any contributions and suggestions aimed at improving the quality of the subsequent versions of this publication. I therefore encourage you to access copies of this Abstract from the Ministry’s Head Office at Amber House or visit the Ministry’s website: www. energyandminerals.go.ug. Robert Kasande PERMANENT SECRETARY 2017 Statistical Abstract – Ministry of Energy and Mineral Development ii TABLE OF CONTENTS FOREWORD ..................................................................................................................................................... -

Health Sector Semi-Annual Monitoring Report FY2020/21

HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development P.O. Box 8147, Kampala www.finance.go.ug MOFPED #DoingMore Health Sector: Semi-Annual Budget Monitoring Report - FY 2020/21 A HEALTH SECTOR SEMI-ANNUAL BUDGET MONITORING REPORT FINANCIAL YEAR 2020/21 MAY 2021 MOFPED #DoingMore Ministry of Finance, Planning and Economic Development TABLE OF CONTENTS ABBREVIATIONS AND ACRONYMS .............................................................................iv FOREWORD.........................................................................................................................vi EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ..................................................................................................vii CHAPTER 1: INTRODUCTION .........................................................................................1 1.1 Background ........................................................................................................................1 CHAPTER 2: METHODOLOGY........................................................................................2 2.1 Scope ..................................................................................................................................2 2.2 Methodology ......................................................................................................................3 2.2.1 Sampling .........................................................................................................................3 -

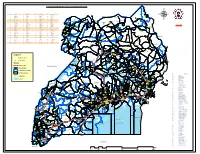

Legend " Wanseko " 159 !

CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA_ELECTORAL AREAS 2016 CONSTITUENT MAP FOR UGANDA GAZETTED ELECTORAL AREAS FOR 2016 GENERAL ELECTIONS CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY CODE CONSTITUENCY 266 LAMWO CTY 51 TOROMA CTY 101 BULAMOGI CTY 154 ERUTR CTY NORTH 165 KOBOKO MC 52 KABERAMAIDO CTY 102 KIGULU CTY SOUTH 155 DOKOLO SOUTH CTY Pirre 1 BUSIRO CTY EST 53 SERERE CTY 103 KIGULU CTY NORTH 156 DOKOLO NORTH CTY !. Agoro 2 BUSIRO CTY NORTH 54 KASILO CTY 104 IGANGA MC 157 MOROTO CTY !. 58 3 BUSIRO CTY SOUTH 55 KACHUMBALU CTY 105 BUGWERI CTY 158 AJURI CTY SOUTH SUDAN Morungole 4 KYADDONDO CTY EST 56 BUKEDEA CTY 106 BUNYA CTY EST 159 KOLE SOUTH CTY Metuli Lotuturu !. !. Kimion 5 KYADDONDO CTY NORTH 57 DODOTH WEST CTY 107 BUNYA CTY SOUTH 160 KOLE NORTH CTY !. "57 !. 6 KIIRA MC 58 DODOTH EST CTY 108 BUNYA CTY WEST 161 OYAM CTY SOUTH Apok !. 7 EBB MC 59 TEPETH CTY 109 BUNGOKHO CTY SOUTH 162 OYAM CTY NORTH 8 MUKONO CTY SOUTH 60 MOROTO MC 110 BUNGOKHO CTY NORTH 163 KOBOKO MC 173 " 9 MUKONO CTY NORTH 61 MATHENUKO CTY 111 MBALE MC 164 VURA CTY 180 Madi Opei Loitanit Midigo Kaabong 10 NAKIFUMA CTY 62 PIAN CTY 112 KABALE MC 165 UPPER MADI CTY NIMULE Lokung Paloga !. !. µ !. "!. 11 BUIKWE CTY WEST 63 CHEKWIL CTY 113 MITYANA CTY SOUTH 166 TEREGO EST CTY Dufile "!. !. LAMWO !. KAABONG 177 YUMBE Nimule " Akilok 12 BUIKWE CTY SOUTH 64 BAMBA CTY 114 MITYANA CTY NORTH 168 ARUA MC Rumogi MOYO !. !. Oraba Ludara !. " Karenga 13 BUIKWE CTY NORTH 65 BUGHENDERA CTY 115 BUSUJJU 169 LOWER MADI CTY !. -

Survey of the Regional Fish Trade

Survey of the regional fish trade Item Type monograph Authors Odongkara, K.; Akumu, J.K.O.; Kyangwa, M.; Wegoye, J.; Kyangwa, I. Publisher Fisheries Resources Research Institute Download date 25/09/2021 23:59:10 Link to Item http://hdl.handle.net/1834/32852 SOCIO-ECONOMIC RESEARCH REPORT 7 LAKE VICTORIA ENVIRONMENTAL MANAGEMENT PROJECT and LAKE VICTORIA FISHERIES RESEARCH PROJECT SURVEY OF THE REGIONAL FISH TRADE Konstantine Odongkara, Joyce Akumu, Mercy Kyangwa, Jonah Wegoye and Ivan Kyangwa FISHERIES RESOURCES RESEARCH INSTITUTE NATIONAL AGRICULTURAL RESEARCH ORGANISATION JINJA, UGANDA. November, 2005 Republic of Uganda Copyright: Ministry of Agriculture, Animal Industry and Fisheries (MAAIF), National Agricultural Research Organization (NARO) and Lake Victoria Environmental Management Project (LVEMP). This publication may be reproduced in whole or part and in any form for education or non-profit uses, without special permission from the copyright holders, provided acknowledgement of the source is made. MAAIF, NARO and LVEMP would appreciate receiving a copy of any publication which uses this publication as a source. No use of this publication may be made for resale or other commercial purpose without the prior written permission of MAAIF, NARO and LVEMP Citation: Odongkara K, M. Kyangwa, J. Akumu, J. Wegoye and I. Kyangwa, 2005: Survey of the regional fish trade. LVEMP Socio-economic Research Report 7. NARO- FIRRI, Jinja Disclaimer: The opinions expressed in this publication are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of MAAIF, NARO or LVEMP. CONTACT ADDRESS Fisheries Resources Research Institute National Agricultural Research Organisation P.O. Box 343, JINJA Uganda Fax: 256-43-120192 Tel. -

Final Report Uganda: Hepatitis E Virus Disease Outbreak

Final Report Uganda: Hepatitis E Virus disease outbreak DREF Operation Operation n° MDRUG036; Glide n° EP-2014-000011-UGA Date of issue: 6 February 2014 Date of disaster: End Dec 2013 Operation manager (responsible for this EPoA): Holger Point of contact (name and title): Ken Kiggundu, Leipe Director Disaster Management, Uganda RC Operation start date: 4 February 2014 Operation end date: 31 July 2014 Overall operation budget: CHF 227,020 Number of people affected: 1,400,000 Number of people to be assisted: 209,100 directly 1,200,000 indirectly Host National Society presence: Ugandan RC, 350 volunteers and seven URCS staff. Red Cross Red Crescent Movement partners actively involved in the operation (if available and relevant): URCS, IFRC, Belgium RC Other partner organizations actively involved in the operation: Ministry of Health of Uganda, Ministry of Education, Ministry of Water, UNFPA, District Security Office. A. Situation analysis Description of the disaster The Ministry of Health (MoH) declared an epidemic of Hepatitis E Virus (HEV) outbreak in Karamoja sub-region of North Eastern Uganda in Napak after ¾ samples that were sent to UVRI1 tested positive for HEV by PCR on 1 Dec 2013. This outbreak was reported to be under control despite the long incubation period and propagating nature of hepatitis E viral disease. As of 27 July 2014, 1,390 cases with 30 deaths were reported 15 deaths of which (50%) reported among expectant mothers. A quick comparison between the epidemic weeks 26 to 30 showed that, only 12 Hepatitis E suspected cases were reported compared to the 276 cases reported between week 1 to 5 when the outbreak had just been declared.