CAP Chain of Command

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

PROMOTION REQUIREMENTS for CAP Members

PROMOTION REQUIREMENTS for CAP Members BY JOHN W. TALBOTT, Lt Col, CAP NEBRASKA WING Developed on 03/15/02 Update on 26 February 2006 AIR FORCE OFFICER RANKS Colonel (O-6) (Col) Second Lieutenant (O-1) (2nd Lt) st Brigadier General (O-7) (Brig Gen) First Lieutenant (O-2) (1 Lt) Captain (O-3) (Capt) Major General (08) (Maj Gen) Major (O-4) (Maj) Army Air Corps Lieutenant Colonel (O-5) (Lt Col) AIR FORCE NCO RANKS Chief Master Sergeant (E-9) (CMsgt) Senior Master Sergeant (E-8) (SMsgt) Master Sergeant (E-7) (Msgt) Technical Sergeant (E-6) (Tsgt) Staff Sergeant (E-5) (Ssgt) CAP Flight Officers Rank Flight Officer: Technical Flight Officer Senior Flight Officer NOTE: The following is a compilation of CAP Regulation 50-17 and CAP 35-5. It is provided as a quick way of evaluating the promotion and training requirements for CAP members, and is not to be treated as an authoritative document, but instead it is provided to assist CAP members in understanding how the two different regulations are inter-related. Since regulations change from time to time, it is recommended that an individual using this document consult the actual regulations when an actual promotion is being evaluated or submitted. Individual section of the pertinent regulations are included, and marked. John W. Talbott, Lt Col, CAP The following are the requirements for various specialty tracks. (Example: promotion to the various ranks for senior Personnel, Cadet Programs, etc.) members in Civil Air Patrol (CAP): For promotion to SFO, one needs to complete 18 months as a TFO, (See CAPR 35-5 for further details.) and have completed level 2: (Attend Squadron Leadership School, complete Initially, all Civil Air Patrol the CAP Officer course ECI Course 13 members who are 18 years or older are or military equivalent, and completes the considered senior members, (with no requirements for a Technician rating in a senior member rank worn), when they specialty track (this is completed for join Civil Air Patrol. -

Police Corporal - Patrol Department: Police Rev 03/14

City of Winder Job Description: Police Corporal - Patrol Department: Police Rev 03/14 EEO Function: Pay Grade: PD-6 EEO Category: Professional Status: Non-Exempt Pay Type: Hourly Position Number: 6346 I. Chain of Command/ Reports To Police Sergeant or through the Chain of Command to the Chief of Police II. Job Summary The functions of a Police Corporal are similar to that of a Police Officer with additional duties as an assistant supervisor or as a shift commander in the absence of a Sergeant. While incumbents are normally assigned to a specific geographic area for patrol, all functional areas of the law enforcement field, including investigation, administration, and training are included. A Police Corporal is also expected to perform field duties relating to response to emergencies, general and directed patrol, investigation of crimes and other non- criminal incidents, traffic enforcement and control, assisting in crime prevention activities, and other law enforcement services and duties as required. A significant degree of initiative, independent judgment, and discretion is required of incumbents to develop, maintain, and successfully perform supervisory tasks in a community oriented, problem solving approach to policing. III. Essential Duties and Functions • Follow and promote Policy & Procedures of the City of Winder. • Ensures that laws and ordinances are enforced and that the public peace and safety is maintained. • Responds to and resolves difficult and sensitive citizen inquiries and complaints. • Ensures the compliance of quality customer services to the public and internal City departments and employees. • Develops and maintains effective working relationships with the community. • Ensures that the department offers and maintains an effective and positive Community Oriented Policing philosophy for the purpose of maintaining the highest possible credibility level within the City. -

Organizational Structure and Responsibility

Policy Urbana Police Department 200 Urbana PD Policy Manual Organizational Structure and Responsibility 200.1 PURPOSE AND SCOPE The organizational structure of this department is designed to create an efficient means to accomplish our mission and goals and to provide for the best possible service to the public. 200.2 DIVISIONS The Leadership Team, which includes the Chief of Police, the Deputy Chief of Police and three Lieutenants, is responsible for administering and managing the Urbana Police Department. There are three divisions in the Police Department as follows: • Services Division • Patrol Division • Investigation Division See attachment: UPD Hierarchy (black and white).pdf 200.2.1 SERVICES DIVISION The Services Division is commanded by a Commander whose primary responsibility is to provide for the effective and efficient management and operations of this division. The Services Division consists of a Police Services Supervisor, Police Services Representatives, the Animal Control Officer, and any staff assistants. 200.2.2 PATROL DIVISION The Patrol Division is commanded by two Commanders whose primary responsibilities are to provide general management direction and control for that Division. The Patrol Division consists of Uniformed Patrol and Street Crimes Unit. 200.2.3 CRIMINAL INVESTIGATIONS DIVISION The Criminal Investigations Division is commanded by a Commander whose primary responsibility is to provide general management direction and control for the Criminal Investigations Division. The Criminal Investigations Division consists of a Sergeant, Detectives and an evidence technician. 200.3 COMMAND PROTOCOL Command protocol in situations involving personnel of different sections or components engaged in a single operation, will be established as follows: (a) The command structure will always follow the chain of command. -

PATROL LIEUTENANT Exempt, Full-Time Police Department

PATROL LIEUTENANT Exempt, Full-Time Police Department Job Summary: Under general supervision of the Operations Captain, responsible for the protection of life and property of the citizens of the city. The employee is expected to perform his or her duties according to state laws, city ordinances and the policies and procedures of the police department. Instructions to the employee are somewhat general but many aspects of the work follow standardized guidelines. However, the employee is frequently required to use independent judgment in order to complete tasks. Equipment Used / Job Locations / Work Environment: The work environment characteristics described here are representative of those an employee encounters while performing the essential functions of this class. Reasonable accommodations may be made to enable individuals with disabilities to perform the essential functions. The employee will operate a variety of equipment including firearms, radio and communications equipment, police vehicles, radar, drug test kit, computer, and fingerprinting and emergency equipment. The demands of this position can be stressful both mentally and physically. The employee may be required to run, jump, bend, climb, crawl, squat, lift and carry heavy objects. The employee will work both indoors and outdoors with the possibility of being exposed to adverse weather conditions and hazardous or extremely dangerous situations. Essential Functions & Job Responsibilities: The duties listed below are intended only as illustrations of the various types of work -

Ranger Handbook

SH 21-76 UNITED STATES ARMY RANGER HANDBOOK "NOT FOR THE WEAK OR FAINTHEARTED” RANGER TRAINING BRIGADE UNITED STATES ARMY INFANTRY SCHOOL FORT BENNING, GEORGIA APRIL 2000 TABLE OF CONTENTS I RANGER CREED II STANDING ORDERS ROGER’S RANGERS III RANGER HISTORY IV RANGER TRAINING BRIGADE HISTORY CHAPTER 1 – LEADERSHIP PRINCIPLES OF LEADERSHIP 1-1 DUTIES/RESPONSIBILITIES 1-2 ASSUMPTION OF COMMAND 1-7 CHAPTER 2 – OPERATIONS TROOP LEADING PROCEDURES 2-1 COMBAT INTELLIGENCE 2-7 WARNING ORDER 2-8 OPERATIONS ORDER 2-11 FRAGMENTARY ORDER 2-17 ANNEXES 2-22 COORDINATION CHECKLISTS 2-29 DOCTRINAL TERMS 2-34 CHAPTER 3 – FIRE SUPPORT CAPABILITIES 3-2 CLOSE AIR SUPPORT 3-4 CALL FOR FIRE 3-5 CHAPTER 4 – MOVEMENT TECHNIQUES 4-2 TACTICAL MARCHES 4-6 DANGER AREAS 4-9 CHAPTER 5 – PATROLLING PLANNING CONSIDERATIONS 5-1 RECONNAISSANCE OPERATIONS 5-6 COMBAT PATROLS 5-13 AMBUSH 5-14 RAID 5-16 DEPARTURE/RE-ENTRY 5-25 LINK-UP 5-27 PATROL BASE 5-30 MOVEMENT TO CONTACT 5-34 CHAPTER 6 – BATTLE DRILLS PLATOON ATTACK 6-1 SQUAD ATTACK 6-5 REACT TO CONTACT 6-8 BREAK CONTACT 6-9 REACT TO AMBUSH 6-11 KNOCK OUT BUNKERS 6-12 ENTER/CLEAR A TRENCH 6-14 BREACH 6-19 CHAPTER 7 – COMMUNICATIONS AN/PRC-119 7-1 AN/PRC-126 7-3 CHAPTER 8 – ARMY AVIATION AIR ASSAULT 8-1 AIR ASSAULT FORMATIONS 8-3 PZ OPERATIONS 8-5 SAFETY 8-8 CHAPTER 9 – WATERBORNE OPERATIONS ONE ROPE BRIDGE 9-1 BOAT POSITIONS 9-8 EMBARKING/DEBARKING 9-11 LANDING SITE 9-11 RIVER MOVEMENT 9-13 FORMATIONS 9-14 CHAPTER 10 – MILITARY MOUNTAINEERING SPECIAL EQUIPMENT 10-1 KNOTS 10-2 BELAYS 10-8 TIGHTENING SYSTEMS 10-10 ROCK -

ATP 3-39.10. Police Operations

ATP 3-39.10 POLICE OPERATIONS AUGUST 2021 DISTRIBUTION RESTRICTION: Approved for Public Release; distribution is unlimited. This publication supersedes ATP 3-39.10, 26 January 2015. Headquarters, Department of the Army This publication is available at the Army Publishing Directorate site (https:// armypubs.army.mil), and the Central Army Registry site (https://atiam.train.army.mil/catalog/dashboard). *ATP 3-39.10 Army Techniques Publication Headquarters No. 3-39.10 Department of the Army Washington, D.C., 24 August 2021 Police Operations Contents Page PREFACE..................................................................................................................... v INTRODUCTION ........................................................................................................ vii Chapter 1 POLICE OPERATIONS SUPPORT TO ARMY OPERATIONS ............................... 1-1 The Police Operations Discipline .............................................................................. 1-1 Principles of Police Operations ................................................................................. 1-4 Rule of Law ................................................................................................................ 1-6 Command and Control of Army Law Enforcement .................................................... 1-7 Operational Environment ........................................................................................... 1-9 Unified Action ......................................................................................................... -

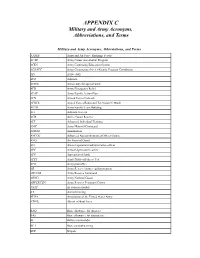

Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms

APPENDIX C Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms AAFES Army and Air Force Exchange Service ACAP Army Career and Alumni Program ACES Army Continuing Education System ACS/FPC Army Community Service/Family Program Coordinator AD Active duty ADJ Adjutant ADSW Active duty for special work AER Army Emergency Relief AFAP Army Family Action Plan AFN Armed Forces Network AFRTS Armed Forces Radio and Television Network AFTB Army Family Team Building AG Adjutant General AGR Active Guard Reserve AIT Advanced Individual Training AMC Army Materiel Command AMMO Ammunition ANCOC Advanced Noncommissioned Officer Course ANG Air National Guard AO Area of operations/administrative officer APC Armored personnel carrier APF Appropriated funds APFT Army Physical Fitness Test APO Army post office AR Army Reserve/Army regulation/armor ARCOM Army Reserve Command ARNG Army National Guard ARPERCEN Army Reserve Personnel Center ASAP As soon as possible AT Annual training AUSA Association of the United States Army AWOL Absent without leave BAQ Basic allowance for quarters BAS Basic allowance for subsistence BC Battery commander BCT Basic combat training BDE Brigade Military and Army Acronyms, Abbreviations, and Terms cont’d BDU Battle dress uniform (jungle, desert, cold weather) BN Battalion BNCOC Basic Noncommissioned Officer Course CAR Chief of Army Reserve CASCOM Combined Arms Support Command CDR Commander CDS Child Development Services CG Commanding General CGSC Command and General Staff College -

Position Profile Police Commander

Position Profile Police Commander The City of Golden Valley is seeking a community-focused, equity-minded, and service-dedicated leader in the policing industry to serve as the next Police Commander. City Contact Kirsten Santelices Deputy City Manager/ Human Resources Director City of Golden Valley 763-593-3989 Who We Are The City of Golden Valley is described as a “sweet spot” in the Minneapolis-St. Paul metro, offering a wide variety of services and programs to its residents, businesses, and visitors. With a population of just over 23,000, and located five miles west of downtown Minneapolis, the city contains numerous parks and trails as well as connections to area regional trails and amenities, providing recreation for all ages and seasons. The City owns and operates Brookview Golden Valley, which is the gold-standard of community gathering spaces, featuring an indoor playground, bar and restaurant, meeting and banquet facilities, golf course, lawn bowling, and curling (for those cold winter months). City Structure City Services Golden Valley is a Statutory Plan B city The City Manager directs the activities of that has been a municipal corporation nine department directors: since 1886. The City is governed by the Administrative Services, Communications, City Council, composed of the Mayor and Fire, Human Resources, Legal, Parks and four Council Members, all elected at-large Recreation, Physical Development, Police, and serving four-year terms. The City and Public Works. operates under the Council/Manager form of government, which means the Across all of its departments, the City City Council sets the policy and overall employs approximately 145 full-time direction for the City and appoints a City employees, 50 paid on-call firefighters, Manager to oversee the day-to-day and about 175 seasonal or variable-hour operations. -

Bowie Police Department - General Orders

Bowie Police Department - General Orders NUMBER: TITLE: NOTIFICATION OF FEDERAL LAW ENFORCEMENT OR THE 445 NATIONAL GUARD EFFECTIVE DATE: 12/21/12 REVIEW DATE: ACCREDITATIONS STANDARDS AUTHORITY TOTAL PAGES CALEA STANDARDS: 2.1.4, 46.1.2, 46.1.3-h Chief John K. Nesky 3 X NEW _ AMENDS _ RESCINDS DATE: I. POLICY [standards][standards] Members of the Bowie Police Department will work closely with federal law enforcement agencies [standards][STANDARDS] and will ensure that timely notifications[STANDARDS][STANDARDS] are made to affected agencie s when necessary. II. EMERGENCY NOTIFICATIONS [total pages] [TOTAL A. Federal Law Enforcement Agency ][TOTAL] 1. If it is determined that a particular federal law enforcement agency is needed for an emergency situation, the highest ranking Officer at the scene should make the request via Communications after consulting with the Chief of Police or the Chief’s designee. If the Chief or the Chief’s designee are unavailable, the Officer will make the request and shall notify a Command Officer as soon as possible. 2. The incidents set forth in section II.A.3 require that the F.B.I. be notified by the Patrol Officer, Investigator, or Communications, depending upon the incident. The Officer should contact the F.B.I.’s Baltimore Field Office as soon as possible after the incident has been confirmed. 3. In the list that follows, the on duty supervisor shall ensure that notification is made to the appropriate federal agency upon receipt of a call for service. The investigating Officer will be responsible for the notification from the scene: a. -

Army Specialist Matthew Powell Upon His Death in Afghanistan

SLS 11RS-484 ORIGINAL Regular Session, 2011 SENATE RESOLUTION NO. 43 BY SENATOR MARIONNEAUX CONDOLENCES. Extends condolences to the family of U.S. Army Specialist Matthew Powell upon his death in Afghanistan. 1 A RESOLUTION 2 To express the sincere and heartfelt condolences of the Senate of the Legislature of 3 Louisiana to the family of United States Army Specialist Matthew Powell upon his 4 death in Afghanistan. 5 WHEREAS, Matthew Powell was a native of Slidell, Louisiana, growing up there, 6 receiving his education there and being an active member of the Grace Memorial Baptist 7 Church from his Sunday school days until he joined the United States Army in 2008 after 8 high school; and 9 WHEREAS, before he departed for the military, Matthew Powell told the 10 congregation how grateful he was to have the church in his life and what a difference he felt 11 it had made to him personally; and 12 WHEREAS, after his basic combat training, Specialist Powell was stationed at Ft. 13 Campbell, Kentucky, where he was a motor transport operator, assigned to Company A, 14 526th Brigade Support Battalion, 2nd Brigade Combat Team, of the legendary 101st Airborne 15 Division (Air Assault); and 16 WHEREAS, Specialist Powell trained hard and sharpened his military skills as he 17 and his fellow soldiers prepared for a year-long deployment to Afghanistan, where the 18 Global War On Terror was heating up; and Page 1 of 2 SLS 11RS-484 ORIGINAL SR NO. 43 1 WHEREAS, Specialist Powell was acutely aware of the constant danger involved 2 with participating in -

Police Sergeant (PDF)

CITY OF CERES POLICE SERGEANT Class specifications are intended to present a descriptive list of the range of duties performed by employees in the class. Specifications are not intended to reflect all duties performed within the job. SUMMARY DESCRIPTION Under direction, plans, directs, supervises, assigns, reviews, and participates in the work of law enforcement staff involved in traffic and field patrol, investigations, crime prevention, community relations, and related services and activities; serves as watch commander on an assigned shift; oversees and participates in all work activities; assumes responsibility for assigned special programs, projects, or department-wide functions or activities; coordinates activities with other agencies; and performs a variety of administrative and technical tasks relative to assigned area of responsibility. REPRESENTATIVE DUTIES The following duties are typical for this classification. Incumbents may not perform all of the listed duties and/or may be required to perform additional or different duties from those set forth below to address business needs and changing business practices. 1. Plan, prioritize, assign, supervise, and review the work of sworn law enforcement staff involved in traffic and field patrol, investigations, crime prevention, community relations, and related services and activities; supervise non-sworn staff in dispatch, records, and property and evidence room as assigned. 2. Serve as first level supervisor/Watch Commander for an assigned shift; prepare and administer briefings; assign patrol beats; supervise and direct sworn and non-sworn staff and activities on assigned shift; conduct personnel, equipment, and building inspections. 3. Prepare, process, and maintain a variety of written reports and records pertaining to assigned activities including daily activity reports; complete payroll for assigned personnel for submission to Finance. -

Police Captain Must Be Flexible and Knowledgeable Enough to Assume the Duties of the Same Rank Within All Divisions of the Department

City of Winder Job Description: Captain - Patrol Commander Department: Police Rev 05/14, 9/14, 4/15, 10/18 Pay Grade: PD-11 Status: Exempt Pay Type: Salary Position Number: 6378 I. Chain of Command/Reports To: Chief of Police II. Job Summary: Under general direction of the Police Chief, plans and coordinates patrol services of the Police Department. The commander conducts and oversees the preliminary and supplementary patrol procedures, traffic enforcement, and is also expected to perform field duties relating to response to emergencies, general and directed patrol, assisting in crime prevention activities, and other law enforcement services and duties as required. A significant degree of initiative, independent judgment, and discretion is required of incumbents to develop, maintain, and successfully perform supervisory tasks in a community oriented, problem solving approach to policing. III. Essential Duties and Functions: Administrative/Financial Follows and promotes policy and procedures of the City of Winder. Informs and advises the Chief of Police on all department issues affecting the City; provides advice, support, and information to other command staff. Assumes management responsibility for Patrol Division and activities, including enforcement of laws, statutes, and ordinances, crime prevention, criminal investigation, emergency communications, and other related law enforcement activities. Assists the Chief of Police in developing and monitoring the department’s budget and is responsible for purchases. Approves purchasing requests and ensures all documents are submitted to the finance department according to timelines established. Reviews invoices and supporting documentation for proper authorization and conformance to requirements. Reviews and/or prepares clear and comprehensive financial, administrative and analytical reports.