Conservation Assessment for Fraser’S Loosestrife (Lysimachia Fraseri Duby)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts

The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: The Vascular Plants of Massachusetts: A County Checklist • First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Somers Bruce Sorrie and Paul Connolly, Bryan Cullina, Melissa Dow Revision • First A County Checklist Plants of Massachusetts: Vascular The A County Checklist First Revision Melissa Dow Cullina, Bryan Connolly, Bruce Sorrie and Paul Somers Massachusetts Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program The Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program (NHESP), part of the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, is one of the programs forming the Natural Heritage network. NHESP is responsible for the conservation and protection of hundreds of species that are not hunted, fished, trapped, or commercially harvested in the state. The Program's highest priority is protecting the 176 species of vertebrate and invertebrate animals and 259 species of native plants that are officially listed as Endangered, Threatened or of Special Concern in Massachusetts. Endangered species conservation in Massachusetts depends on you! A major source of funding for the protection of rare and endangered species comes from voluntary donations on state income tax forms. Contributions go to the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Fund, which provides a portion of the operating budget for the Natural Heritage & Endangered Species Program. NHESP protects rare species through biological inventory, -

Research.Pdf (630.5Kb)

IRON, WINE, AND A WOMAN NAMED LUCY: LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY IN ST. JAMES, MISSOURI _______________________________________ A Thesis presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Master of Arts _____________________________________________________ by BRENT ALEXANDER Dr. Soren Larsen, Thesis Supervisor AUGUST 2008 The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the thesis entitled IRON, WINE, AND A WOMAN NAMED LUCY: LANDSCAPES OF MEMORY IN ST. JAMES, MISSOURI presented by Brent Alexander, a candidate for the degree of Master of Arts, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. Professor Soren Larsen Professor Larry Brown Professor Elaine Lawless Dedicated to the people of St. James …and to Lucy – we are indebted to the love you had for this town. ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS I would like to thank Dr. Soren Larsen for being an outstanding advisor to me during my graduate school experience. I learned a lot. I would like to thank the other members of my thesis committee – Dr. Larry Brown and Dr. Elaine Lawless – for all of their great ideas, challenging critiques, and the time they devoted to proofreading this lengthy piece of work. Thanks are due as well to other members of the Geography Department faculty and the greater academic community who offered advice and constructive criticism throughout the development of this research project. I would like to send a special thank you to Dr. John Fraser Hart for giving me the opportunity to say that I have fielded criticism from a legend in the discipline. -

Medicinal Practices of Sacred Natural Sites: a Socio-Religious Approach for Successful Implementation of Primary

Medicinal practices of sacred natural sites: a socio-religious approach for successful implementation of primary healthcare services Rajasri Ray and Avik Ray Review Correspondence Abstract Rajasri Ray*, Avik Ray Centre for studies in Ethnobiology, Biodiversity and Background: Sacred groves are model systems that Sustainability (CEiBa), Malda - 732103, West have the potential to contribute to rural healthcare Bengal, India owing to their medicinal floral diversity and strong social acceptance. *Corresponding Author: Rajasri Ray; [email protected] Methods: We examined this idea employing ethnomedicinal plants and their application Ethnobotany Research & Applications documented from sacred groves across India. A total 20:34 (2020) of 65 published documents were shortlisted for the Key words: AYUSH; Ethnomedicine; Medicinal plant; preparation of database and statistical analysis. Sacred grove; Spatial fidelity; Tropical diseases Standard ethnobotanical indices and mapping were used to capture the current trend. Background Results: A total of 1247 species from 152 families Human-nature interaction has been long entwined in has been documented for use against eighteen the history of humanity. Apart from deriving natural categories of diseases common in tropical and sub- resources, humans have a deep rooted tradition of tropical landscapes. Though the reported species venerating nature which is extensively observed are clustered around a few widely distributed across continents (Verschuuren 2010). The tradition families, 71% of them are uniquely represented from has attracted attention of researchers and policy- any single biogeographic region. The use of multiple makers for its impact on local ecological and socio- species in treating an ailment, high use value of the economic dynamics. Ethnomedicine that emanated popular plants, and cross-community similarity in from this tradition, deals health issues with nature- disease treatment reflects rich community wisdom to derived resources. -

Introduction to Common Native & Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska

Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska Cover photographs by (top to bottom, left to right): Tara Chestnut/Hannah E. Anderson, Jamie Fenneman, Vanessa Morgan, Dana Visalli, Jamie Fenneman, Lynda K. Moore and Denny Lassuy. Introduction to Common Native & Potential Invasive Freshwater Plants in Alaska This document is based on An Aquatic Plant Identification Manual for Washington’s Freshwater Plants, which was modified with permission from the Washington State Department of Ecology, by the Center for Lakes and Reservoirs at Portland State University for Alaska Department of Fish and Game US Fish & Wildlife Service - Coastal Program US Fish & Wildlife Service - Aquatic Invasive Species Program December 2009 TABLE OF CONTENTS TABLE OF CONTENTS Acknowledgments ............................................................................ x Introduction Overview ............................................................................. xvi How to Use This Manual .................................................... xvi Categories of Special Interest Imperiled, Rare and Uncommon Aquatic Species ..................... xx Indigenous Peoples Use of Aquatic Plants .............................. xxi Invasive Aquatic Plants Impacts ................................................................................. xxi Vectors ................................................................................. xxii Prevention Tips .................................................... xxii Early Detection and Reporting -

Hummingbird Gardening for Wisconsin Gardeners Using Native Plants

HUMMINGBIRD GARDENING FOR WISCONSIN GARDENERS USING NATIVE PLANTS “The hummingbird is seen to stop thus some instants before a flower, and dart off like a gleam to another; it visits them all, plunging its little tongue into their bosom, caressing them with its wings, without ever settling, but at the same time ever quitting them.” W.C.L. Martin, General History of Hummingbirds, Circa 1840. KEY ELEMENTS OF A SUCCESSFUL HUMMINGBIRD GARDEN A “Wildscape” Filled With Native Plants Loved By Hummingbirds With Something in Bloom All Season Long! Well-Maintained Hummingbird Feeders from April through October (with no instant nectar or red food coloring) Cover, Perching & Preening Spots (trees & shrubs with dense, tiny branches for perching, shepherd’s hooks, tree snags, brush piles) Inclusion of Water Feature---water should be very shallow and feature should include waterfall and dripper and/or misting device to keep water moving and fresh Use of Hummingbird Beacons (red ribbons, metallic streamers, gazing ball, or any red object near feeders and flowers, especially in early spring!) NATIVE HUMMINGBIRD GARDENING & WILDSCAPING TIPS Plant Red or Orange Tubular Flowers with no fragrance (although some flowers of other colors can also be highly attractive to hummingbirds) Use Native Plants, Wildflowers & Single Flowers Plants with Many Small Blossoms Pointing Sideways or Down Use Plants With Long Bloom Period Use Plants that Bloom Profusely During August & September Create Mass Plantings (not just a single plant) of Flowers that are Hummingbird Favorites Eliminate or Greatly Decrease the Use of Turf Grass to Create a Natural Hummingbird and Wild Bird Habitat (native groundcovers can be used in place of turf grass if desired) Use Natural and/or Organic Mulches (Pine Needles, Leaves, Bark) Whenever Possible Height of Plants should be Tall, not Short (or utilize hanging baskets or large containers for shorter plants)---remember, hummingbirds are birds of the air and not the ground. -

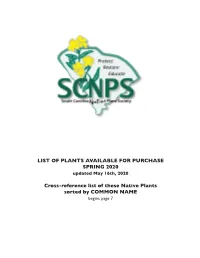

List of Plants Available for Purchase Spring 2020 Cross-Reference List Of

List of pLants avaiLabLe for purchase spring 2020 updated May 16th, 2020 cross-reference list of these native plants sorted by coMMon naMe begins page 7 SC-NPS NATIVE PLANT PRICING Rev May 16th, 2020 – Sort by TYPE + SCIENTIFIC NAME’ Type SCIENTIFIC NAME COMMON NAME Size Price A NOG – concentrate (makes 16 gal.) NOG 32oz $18.00 A NOG – granules NOG 4lbs. $6.00 FERNS & FERN ALLIES F Adiantum pedatum Fern – Northern Maidenhair 1g $10.00 F Asplenium platyneuron Fern – Ebony Spleenwort 1 tall $8.00 F Asplenium platyneuron Fern – Ebony Spleenwort 4” $4.00 F Athyrium filix-femina v. Asplenoides Fern – Southern Lady 3” $4.00 F Diplazium pycnocarpon Fern – Narrow Leaf Glade 3” $4.00 F Dryopteris celsa Fern – Log 1g $10.00 F Dryopteris intermedia Fern – Fancy Fern 1g $8.00 F Dryopteris ludoviciana Fern – Southern Wood 1g $10.00 F Onoclea sensibilis Fern – Sensitive 3” $4.00 F Osmunda cinnamomeam Fern – Cinnamon 1g $10.00 F Osmunda regalis Fern – Royal 1g $10.00 F Polystichum acrostichoides Fern – Christmas 1g $8.00 F Thelypteris confluens Fern – Marsh 1g $10.00 F Woodwardia areolata Fern – Netted chain 3” $4.00 GRASSES & SEDGES G Andropogon gerardii Bluestem – big 1g $8.00 G Carex appalachica Sedge – Appalachian 1g $6.00 G Carex appalachica Sedge – Appalachian 4”Tall $4.00 G Carex flaccasperma Sedge – Blue Wood 1g $8.00 G Carex plantaginea Sedge – Seersucker sedge 1g $6.00 G Chasmanthium latifolium Riveroats 1g $6.00 G Juncus effusus Common Rush 1g $6.00 G Muhlenbergia capillaris Muhly grass, Pink 1g $6.00 G Muhlenbergia capillaris Muhly grass, -

Haas Halo Hydrangea

Out in the Garden Rockport Garden Club, May 2021 What alternatives to harmful insecticides and The Garden Diary: pesticides are available to us? What’s Bugging Stop bugs BEFORE they become a problem: You? 1. Clean up weeds and standing water in your yard which host insects. Did you know there are 200,000,000 insects for every man, woman, and child on earth? Yes, 2. Keep your plants healthy. A healthy plant that is 200 million for each of us! Insects will has its own defenses against many predators. always outnumber us. That is the bad news. 3. Don’t over-fertilize. Too much fertilizer cre- ates weak growth which attracts insects. The good news is that most bugs are either bene- ficial or benign, having no noticeable impact on 4. Be sure plants receive adequate water. Too our lives. We rarely give the good bugs credit little water stresses plants and attracts in- for the work they do. Bees and butterflies polle- sects. nate our plants. Tiny parasitic wasps lay eggs on 5. If bugs are large enough to hand pick, squish larger in- sects and them or put them in a jar of soapy water. kill them 6. Use a garden hose to spray off other insects. in the pro- 7. Create an oasis for birds and butterflies cess. Pray- ing mantis- since birds and other bugs are the worst ene- es kill bee- mies of bad bugs. tles and spiders in Ultimately you may need to use a pesticide. Opt large num- for an organic product whenever possible. -

Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) 405-417 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; Download Unter

ZOBODAT - www.zobodat.at Zoologisch-Botanische Datenbank/Zoological-Botanical Database Digitale Literatur/Digital Literature Zeitschrift/Journal: Linzer biologische Beiträge Jahr/Year: 2003 Band/Volume: 0035_1 Autor(en)/Author(s): Altenhofer Ewald, Pschorn-Walcher Hubert Artikel/Article: Biologische Notizen über die Blattwespen-Gattungen Metallus FORBES, Monostegia A. COSTA und Phymatocera DAHLBOM (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) 405-417 © Biologiezentrum Linz/Austria; download unter www.biologiezentrum.at Linzer biol. Beitr. 35/1 405-417 30.6.2003 Biologische Notizen über die Blattwespen-Gattungen Metallus FORBES, Monostegia A. COSTA und Phymatocera DAHLBOM (Hymenoptera: Tenthredinidae) E. ALTENHOFER & H. PSCHORN-WALCHER Abstract: Larval collections and rearings have been made of the European species of the sawfly genera Metallus, Monostegia, and Phymatocera. The biology of Metallus albipes, a leaf-miner specialized on raspberries, is described in some detail. M. pumilus has been reared mainly from dewberries (Rubus caesius), less often from rock bramble (R. saxatilis), but has rarely been found on blackberries (R. fruticosus agg.). M. lanceolatus, mining the leaves of wood avens (Geum urbanum), is also briefly dealt with. The larvae of these leaf-miners are described and a total of 11 species of parasitoids have been reared from them, including 3 highly specific Ichneumonid species of the genera Lathrolestes and Grypocentrus. Monostegia nigra, an entirely black sawfly species separated from M. abdominalis by TAEGER (1987), has been reared from Lysimachia punctata in gardens. In contrast to M. abdominalis, frequently reared also from L. vulgaris (yellow loosestrife), M. nigra lays several eggs dispersed over a leaf (not in an oblong cluster) and the head capsule of the larvae is uniformly yellowish (not with a dark stripe on the vertex). -

Numismata Graeca; Greek Coin-Types, Classified For

NUMISMATA GRAECA GREEK COIN-TYPES CLASSIFIED FOR IMMEDIATE IDENTIFICATION PROTAT BROTHERS, PRINTERS, MACON (fRANCb). NUMISMATA GRAEGA GREEK GOIN-TYPES GLASSIFIED FOR IMMEDIATE IDENTIFICATION BY L^" CI flu pl-.M- ALTAR No. ALTAR Metal Xo. Pi.ACi: OBVEnSE Reverse V\t Denom . 1)a Pl.A Ri;it:iii;n(:i; SlZE II Nicaen. AVTKAINETPAIANOC. Large altar ready laid with /E.8 Tra- II un teriaii (]oll Jiilhijni:t. Ileadof Trajan r., laur. wood and havin^' door in 20 jan. p. 247, Xo 8. front; beneath AIOC. Ves- Prusiiis AYTKAilAPIIEBAI EniMAPKOYnAAN. P. I. R. .M. Pontus, etc, pasian, ad IIy])ium. TnOYEinAIIAN KIOYOY APOYAN- 22.5 12 p. 201, No 1. A. D. Billiynia. Headof Altar. nnPOYIIEII- eYHATOY. 200 Vespasian to r., laur. \:i .Aiiiasia. (]ara- 10, \o 31, AYKAIMAYP AAPCeYANTAMACIACM... , , p. Ponliirt. ANTnNINOC-Biislof in ex., eTCH. Altar of 1.2 caila. Caracalla r., laureale two stages. 30 A. n. in Paludamentum and 208 ciiirass. 14 l ariiini. Hust of Pallas r., in hel n A Garlanded altar, yE.5 H. C. R. M. Mysia, p. 1(11, Mijsiu. niet ; borderofdots. 12.5 P I 200 No 74. to Au- gus- tus. 15 Smyrna. TIB€PIOC C€BAC- ZMYPNAICON lonia. TOC- Ilead of Tibe- lePGONYMOC. Altar -ar- .E.65 Tibe- B. M. lonia, p. 268, rius r.,laur. landed. 10 No 263. 16 .\ntioch. BOYAH- Female bust ANTlOXenN- Altar. ^E.7 Babelon,/»^. Wadd., C.nria. r., veiled. 18 p. 116, \o 21.')9. 17 ANTIOXeWN cesAC CYNAPXiA AFAAOY .E.6 Au- ,, ,, No 2165. TOY- Nil^e staiiding. TOY AfAAOY. Altar, 15 gus- tus. -

HYDRANGEAS for the LANDSCAPE Bill Hendricks Klyn Nurseries

HYDRANGEAS FOR THE LANDSCAPE Bill Hendricks Klyn Nurseries Hydrangea arborescens Native species found growing in damp, shady areas of central and southern Ohio. Will flower in deep shade. a. ‘Annabelle’ Cultivar with large 12” flower heads adaptable to sunny and partially shaded sites. a. radiata Green foliage has a silvery underside that shows off with in a light breeze. Flat cluster of white flowers in mid summer on new wood. a. r. ‘Samantha’ Large round white heads held above green foliage with a silvery underside. macrophylla This is the species from which the majority of familiar cultivated hydrangeas are derived. A few of the vast number of cultivars of this species include: Hortensia forms All Summer Beauty Large heads of blue or pink all summer. Blooms on current season’s wood. Endless Summer™ Large heads of pink or blue bloom on new or old wood. Flowers all summer. Enziandom Gentian blue flowers are held against dark green foliage. Forever Pink Rich clear pink flowers. Goliath Huge heads of soft pink to pale blue, dark green foliage. Harlequin Remarkable bicolor rose-pink flowers have a band of white around each floret. Give a little added protection in winter. Masja Large red flowers, glossy foliage. Mme. Emile Mouillere Reliable white hydrangea has either a pink or blue eye depending on soil pH Nigra Black stems contrast nicely with dusty rose mophead flowers. Nikko Blue Large deep blue flowers. Parzifal Tight mopheads of pink to deep blue depending on pH. Flowers held upright on strong stems. Penny Mac Reblooming clear blue flowers, appear on new or old wood Pia Dwarf compact form displays full size rose pink flowers. -

Smithsonian Miscellaneous Collections

SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 95, NUMBER 8 THOMAS WALTER, BOTANIST APR 22 1936 BY WILLIAM R. MAXON U. S. National Museum (Publication 3388) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION APRIL 22, 1936 1 SMITHSONIAN MISCELLANEOUS COLLECTIONS VOLUME 95. NUMBER 8 THOMAS WALTER, BOTANIST BY WILLIAM R. MAX ON U. S. National Museum (Publication 3388) CITY OF WASHINGTON PUBLISHED BY THE SMITHSONIAN INSTITUTION APRIL 22, 1936 Z^<i £ovi (gaitimovi ^rtee BALTIMORE, MD., U. 8. A. THOMAS WALTER, BOTANIST By WILLIAM R. MAXON U. S. National Museum The first descriptive treatise upon the flowering plants of any definite region in eastern North America, using the binomial system of nomenclature, is the " Flora Caroliniana " of Thomas Walter, published at London in 1788 by the famous botanical collector John Fraser, at the latter's expense. This important and historically inter- esting volume, the specimens upon which it is based, Walter's botanical activity in South Carolina, and visits by more than one eminent botanist to his secluded grave on the banks of the Santee River have been the subjects of several articles, yet comparatively little is known about the man himself. The present notice is written partly with the purpose of bringing together scattered source references, correcting an unusual and long-standing error as to the date of Walter's death, and furnishing data recently obtained as to his marriages, and partly in the hope that something may still be discovered as to liis extraction, education, and early life and the circumstances of his removal to this country. For the sake of clearness and both general and local interest these points may be dealt with somewhat categorically. -

Harmonia+ and Pandora+

Appendix A Harmonia+PL – procedure for negative impact risk assessment for invasive alien species and potentially invasive alien species in Poland QUESTIONNAIRE A0 | Context Questions from this module identify the assessor and the biological, geographical & social context of the assessment. a01. Name(s) of the assessor(s): first name and family name 1. Wojciech Adamowski 2. Monika Myśliwy – external expert 3. Zygmunt Dajdok acomm01. Comments: degree affiliation assessment date (1) dr Białowieża Geobotanical Station, Faculty of Biology, 15-01-2018 University of Warsaw (2) dr Department of Plant Taxonomy and Phytogeography, 26-01-2018 Faculty of Biology, University of Szczecin (3) dr Department of Botany, Institute of Environmental 31-01-2018 Biology, University of Wrocław a02. Name(s) of the species under assessment: Polish name: Niecierpek pomarańczowy Latin name: Impatiens capensis Meerb. English name: Orange balsam acomm02. Comments: The nomenclature was adapted after Mirek et al. (2002 – P). Latin name is widely accepted (The Plant List 2013 – B). Synonyms of the Latin name: Balsamina capensis (Meerb.) DC., Balsamina fulva Ser., Chrysaea biflora (Walter) Nieuwl. & Lunell, Impatiens biflora Walter, Impatiens fulva Nutt., Impatiens maculata Muhl., Impatiens noli-tangere ssp. biflora (Walter) Hultén A synonym of the Polish name: niecierpek przylądkowy Synonyms of the English name: orange jewelweed, spotted touch-me-not Polish name (synonym I) Polish name (synonym II) niecierpek przylądkowy – Latin name (synonym I) Latin name (synonym II) Impatiens biflora Impatiens fulva English name (synonym I) English name (synonym II) Common jewelweed Spotted jewelweed a03. Area under assessment: Poland acomm03. Comments: – a04. Status of the species in Poland. The species is: native to Poland alien, absent from Poland alien, present in Poland only in cultivation or captivity alien, present in Poland in the environment, not established X alien, present in Poland in the environment, established aconf01.