Chapter 8 Fish Fauna

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Seasonal and Diel Movements and Habitat Use of Robust Redhorses in the Lower Savannah River. Georgia, and South Carolina

Transactions of the American FisheriesSociety 135:1145-1155, 2006 [Article] © Copyright by the American Fisheries Society 2006 DO: 10.1577/705-230.1 Seasonal and Diel Movements and Habitat Use of Robust Redhorses in the Lower Savannah River, Georgia and South Carolina TIMOTHY B. GRABOWSKI*I Department of Biological Sciences, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina,29634-0326, USA J. JEFFERY ISELY U.S. Geological Survey, South Carolina Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit, Clemson University, Clemson, South Carolina, 29634-0372, USA Abstract.-The robust redhorse Moxostonta robustum is a large riverine catostomid whose distribution is restricted to three Atlantic Slope drainages. Once presumed extinct, this species was rediscovered in 1991. Despite being the focus of conservation and recovery efforts, the robust redhorse's movements and habitat use are virtually unknown. We surgically implanted pulse-coded radio transmitters into 17 wild adults (460-690 mm total length) below the downstream-most dam on the Savannah River and into 2 fish above this dam. Individuals were located every 2 weeks from June 2002 to September 2003 and monthly thereafter to May 2005. Additionally, we located 5-10 individuals every 2 h over a 48-h period during each season. Study fish moved at least 24.7 ± 8.4 river kilometers (rkm; mean ± SE) per season. This movement was generally downstream except during spring. Some individuals moved downstream by as much as 195 rkm from their release sites. Seasonal migrations were correlated to seasonal changes in water temperature. Robust redhorses initiated spring upstream migrations when water temperature reached approximately 12'C. Our diel tracking suggests that robust redhorses occupy small reaches of river (- 1.0 rkm) and are mainly active diumally. -

Carmine Shiner (Notropis Percobromus) in Canada

COSEWIC Assessment and Update Status Report on the Carmine Shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada THREATENED 2006 COSEWIC COSEPAC COMMITTEE ON THE STATUS OF COMITÉ SUR LA SITUATION ENDANGERED WILDLIFE DES ESPÈCES EN PÉRIL IN CANADA AU CANADA COSEWIC status reports are working documents used in assigning the status of wildlife species suspected of being at risk. This report may be cited as follows: COSEWIC 2006. COSEWIC assessment and update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. vi + 29 pp. (www.sararegistry.gc.ca/status/status_e.cfm). Previous reports COSEWIC 2001. COSEWIC assessment and status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus and rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. v + 17 pp. Houston, J. 1994. COSEWIC status report on the rosyface shiner Notropis rubellus in Canada. Committee on the Status of Endangered Wildlife in Canada. Ottawa. 1-17 pp. Production note: COSEWIC would like to acknowledge D.B. Stewart for writing the update status report on the carmine shiner Notropis percobromus in Canada, prepared under contract with Environment Canada, overseen and edited by Robert Campbell, Co-chair, COSEWIC Freshwater Fishes Species Specialist Subcommittee. In 1994 and again in 2001, COSEWIC assessed minnows belonging to the rosyface shiner species complex, including those in Manitoba, as rosyface shiner (Notropis rubellus). For additional copies contact: COSEWIC Secretariat c/o Canadian Wildlife Service Environment Canada Ottawa, ON K1A 0H3 Tel.: (819) 997-4991 / (819) 953-3215 Fax: (819) 994-3684 E-mail: COSEWIC/[email protected] http://www.cosewic.gc.ca Également disponible en français sous le titre Évaluation et Rapport de situation du COSEPAC sur la tête carminée (Notropis percobromus) au Canada – Mise à jour. -

Notropis Girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis Tetranema)

Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Species Status Assessment Report for the Arkansas River Shiner (Notropis girardi) and Peppered Chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) Arkansas River shiner (bottom left) and peppered chub (top right - two fish) (Photo credit U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service) Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 Version 1.0a October 2018 U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service Region 2 Albuquerque, NM This document was prepared by Angela Anders, Jennifer Smith-Castro, Peter Burck (U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (USFWS) – Southwest Regional Office) Robert Allen, Debra Bills, Omar Bocanegra, Sean Edwards, Valerie Morgan (USFWS –Arlington, Texas Field Office), Ken Collins, Patricia Echo-Hawk, Daniel Fenner, Jonathan Fisher, Laurence Levesque, Jonna Polk (USFWS – Oklahoma Field Office), Stephen Davenport (USFWS – New Mexico Fish and Wildlife Conservation Office), Mark Horner, Susan Millsap (USFWS – New Mexico Field Office), Jonathan JaKa (USFWS – Headquarters), Jason Luginbill, and Vernon Tabor (Kansas Field Office). Suggested reference: U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service. 2018. Species status assessment report for the Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema), version 1.0, with appendices. October 2018. Albuquerque, NM. 172 pp. Arkansas River Shiner and Peppered Chub SSA, October 2018 EXECUTIVE SUMMARY ES.1 INTRODUCTION (CHAPTER 1) The Arkansas River shiner (Notropis girardi) and peppered chub (Macrhybopsis tetranema) are restricted primarily to the contiguous river segments of the South Canadian River basin spanning eastern New Mexico downstream to eastern Oklahoma (although the peppered chub is less widespread). Both species have experienced substantial declines in distribution and abundance due to habitat destruction and modification from stream dewatering or depletion from diversion of surface water and groundwater pumping, construction of impoundments, and water quality degradation. -

Edna Assay Development

Environmental DNA assays available for species detection via qPCR analysis at the U.S.D.A Forest Service National Genomics Center for Wildlife and Fish Conservation (NGC). Asterisks indicate the assay was designed at the NGC. This list was last updated in June 2021 and is subject to change. Please contact [email protected] with questions. Family Species Common name Ready for use? Mustelidae Martes americana, Martes caurina American and Pacific marten* Y Castoridae Castor canadensis American beaver Y Ranidae Lithobates catesbeianus American bullfrog Y Cinclidae Cinclus mexicanus American dipper* N Anguillidae Anguilla rostrata American eel Y Soricidae Sorex palustris American water shrew* N Salmonidae Oncorhynchus clarkii ssp Any cutthroat trout* N Petromyzontidae Lampetra spp. Any Lampetra* Y Salmonidae Salmonidae Any salmonid* Y Cottidae Cottidae Any sculpin* Y Salmonidae Thymallus arcticus Arctic grayling* Y Cyrenidae Corbicula fluminea Asian clam* N Salmonidae Salmo salar Atlantic Salmon Y Lymnaeidae Radix auricularia Big-eared radix* N Cyprinidae Mylopharyngodon piceus Black carp N Ictaluridae Ameiurus melas Black Bullhead* N Catostomidae Cycleptus elongatus Blue Sucker* N Cichlidae Oreochromis aureus Blue tilapia* N Catostomidae Catostomus discobolus Bluehead sucker* N Catostomidae Catostomus virescens Bluehead sucker* Y Felidae Lynx rufus Bobcat* Y Hylidae Pseudocris maculata Boreal chorus frog N Hydrocharitaceae Egeria densa Brazilian elodea N Salmonidae Salvelinus fontinalis Brook trout* Y Colubridae Boiga irregularis Brown tree snake* -

Early Development of the Devils River Minnow, Dionda Diaboli (Cyprinidae)

THE SOUTHWESTERN NATURALIST 52(3):378–385 SEPTEMBER 2007 EARLY DEVELOPMENT OF THE DEVILS RIVER MINNOW, DIONDA DIABOLI (CYPRINIDAE) JULIE HULBERT,TIMOTHY H. BONNER,* JOE N. FRIES,GARY P. GARRETT, AND DAVID R. PENDERGRASS Department of Biology, Texas State University, 601 University Drive, San Marcos, TX 78666 (JH, THB, DRP) National Fish Hatchery and Technology Center, 500 McCarty Lane, San Marcos, TX 78666 (JNF) Texas Parks and Wildlife Department, 5103 Junction Highway, Ingram, TX 78025 (GPG) *Correspondent: [email protected] ABSTRACT—The Devils River minnow (Dionda diaboli) coexists with at least 2 congeners and several other cyprinids throughout its range in southern Texas and northern Mexico. Larval and juvenile descriptions are needed to monitor D. diaboli larvae and juveniles as part of recovery efforts for this species of conservation concern. The purpose of this study was to describe and quantify characteristics of early life stages of D. diaboli from hatching to 128 d post hatch to facilitate larval and juvenile identification. Descriptive characters include mid-lateral band of melanophores by Day 8 (.5.1 mm SL; .5.4 mm TL), mid-lateral band of melanophores separate from a rounded caudal spot and lateral snout-to-eye melanophores by Day 16 (.5.8 mm SL; .6.3 mm TL), initial coiling of intestine by Day 32 (.6.2 mm SL; .7.2 mm TL), wedge-shaped caudal spot by Day 64 (.8.7 mm SL; .10.0 mm TL), and melanophores around scale margins and mid-lateral double dashes along lateral line by Day 128 (.13.5 mm SL; .16.0 mm TL). -

Rio Grande National Forest Draft Assessment 5 At-Risk Species

Rio Grande National Forest- Draft Assessment 5 Identifying and Assessing At-risk Species Rio Grande National Forest Draft Assessment 5 Identifying and Assessing At-risk Species Contents Introduction .............................................................................................................................................. 1 Information Sources and Gaps .............................................................................................................. 2 Existing Forest Plan Direction .............................................................................................................. 2 Scale of Analysis (Area of Influence) ................................................................................................... 4 Assessment 5 Development Process ..................................................................................................... 4 Federally Recognized Species .................................................................................................................. 6 Uncompahgre Fritillary Butterfly ......................................................................................................... 6 Black-footed Ferret ............................................................................................................................... 8 Canada Lynx ....................................................................................................................................... 11 New Mexico Meadow Jumping Mouse ............................................................................................. -

Rio Costilla Habitat Improvement Project

Decision Memo Rio Costilla Habitat Improvement Project USDA Forest Service, Southwestern Region Questa Ranger District, Carson National Forest Taos County, New Mexico (Sections 1, 2, 11, 12, 14, and 15 of Township 30 North, Range 15 East) Background An interdisciplinary analysis on this project was conducted and is documented in a project record. Source documents from the project record are incorporated by reference throughout this decision memo by showing the document number in brackets [PR #]. Please refer to Appendix A for the project record index. The Questa Ranger District of the Carson National Forest, in partnership with the New Mexico Department of Game and Fish (NMDGF) and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service, proposes to improve in- stream habitat conditions within the Rio Costilla [PR #77, 128]. The Valle Vidal Unit of the Carson National Forest attracts hundreds of anglers annually. The Rio Costilla is the largest stream in the Valle Vidal and a favorite among anglers. Anglers travel to this area in large part to pursue the native Rio Grande cutthroat trout. Long-term operations of the Costilla Reservoir and Dam have channelized the Rio Costilla, which has become inadequate for holding fish during low-flow conditions and through the winter. The Rio Costilla has become shallow and wide in many spots, and future efforts to re-establish self-sustaining populations of Rio Grande cutthroat trout may not be successful without active management. Since 2001, Rio Grande cutthroat trout and other native fish population restoration efforts have been ongoing within the upper Rio Costilla watershed. Restoration efforts in this section of the Rio Costilla have included the construction of the Rio Costilla terminal fish barrier in October 2016. -

RFP No. 212F for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub

1 RFP No. 212f for Endangered Species Research Projects for the Prairie Chub Final Report Contributing authors: David S. Ruppel, V. Alex Sotola, Ozlem Ablak Gurbuz, Noland H. Martin, and Timothy H. Bonner Addresses: Department of Biology, Texas State University, San Marcos, Texas 78666 (DSR, VAS, NHM, THB) Kirkkonaklar Anatolian High School, Turkish Ministry of Education, Ankara, Turkey (OAG) Principal investigators: Timothy H. Bonner and Noland H. Martin Email: [email protected], [email protected] Date: July 31, 2017 Style: American Fisheries Society Funding sources: Texas Comptroller of Public Accounts, Turkish Ministry of Education- Visiting Scholar Program (OAG) Summary Four hundred mesohabitats were sampled from 36 sites and 20 reaches within the upper Red River drainage from September 2015 through September 2016. Fishes (N = 36,211) taken from the mesohabitats represented 14 families and 49 species with the most abundant species consisting of Red Shiner Cyprinella lutrensis, Red River Shiner Notropis bairdi, Plains Minnow Hybognathus placitus, and Western Mosquitofish Gambusia affinis. Red River Pupfish Cyprinodon rubrofluviatilis (a species of greatest conservation need, SGCN) and Plains Killifish Fundulus zebrinus were more abundant within prairie streams (e.g., swift and shallow runs with sand and silt substrates) with high specific conductance. Red River Shiner (SGCN), Prairie Chub Macrhybopsis australis (SGCN), and Plains Minnow were more abundant within prairie 2 streams with lower specific conductance. The remaining 44 species of fishes were more abundant in non-prairie stream habitats with shallow to deep waters, which were more common in eastern tributaries of the upper Red River drainage and Red River mainstem. Prairie Chubs comprised 1.3% of the overall fish community and were most abundant in Pease River and Wichita River. -

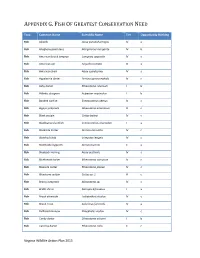

Fish of Greatest Conservation Need

APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Taxa Common Name Scientific Name Tier Opportunity Ranking Fish Alewife Alosa pseudoharengus IV a Fish Allegheny pearl dace Margariscus margarita IV b Fish American brook lamprey Lampetra appendix IV c Fish American eel Anguilla rostrata III a Fish American shad Alosa sapidissima IV a Fish Appalachia darter Percina gymnocephala IV c Fish Ashy darter Etheostoma cinereum I b Fish Atlantic sturgeon Acipenser oxyrinchus I b Fish Banded sunfish Enneacanthus obesus IV c Fish Bigeye jumprock Moxostoma ariommum III c Fish Black sculpin Cottus baileyi IV c Fish Blackbanded sunfish Enneacanthus chaetodon I a Fish Blackside darter Percina maculata IV c Fish Blotched chub Erimystax insignis IV c Fish Blotchside logperch Percina burtoni II a Fish Blueback Herring Alosa aestivalis IV a Fish Bluebreast darter Etheostoma camurum IV c Fish Blueside darter Etheostoma jessiae IV c Fish Bluestone sculpin Cottus sp. 1 III c Fish Brassy Jumprock Moxostoma sp. IV c Fish Bridle shiner Notropis bifrenatus I a Fish Brook silverside Labidesthes sicculus IV c Fish Brook Trout Salvelinus fontinalis IV a Fish Bullhead minnow Pimephales vigilax IV c Fish Candy darter Etheostoma osburni I b Fish Carolina darter Etheostoma collis II c Virginia Wildlife Action Plan 2015 APPENDIX G. FISH OF GREATEST CONSERVATION NEED Fish Carolina fantail darter Etheostoma brevispinum IV c Fish Channel darter Percina copelandi III c Fish Clinch dace Chrosomus sp. cf. saylori I a Fish Clinch sculpin Cottus sp. 4 III c Fish Dusky darter Percina sciera IV c Fish Duskytail darter Etheostoma percnurum I a Fish Emerald shiner Notropis atherinoides IV c Fish Fatlips minnow Phenacobius crassilabrum II c Fish Freshwater drum Aplodinotus grunniens III c Fish Golden Darter Etheostoma denoncourti II b Fish Greenfin darter Etheostoma chlorobranchium I b Fish Highback chub Hybopsis hypsinotus IV c Fish Highfin Shiner Notropis altipinnis IV c Fish Holston sculpin Cottus sp. -

Endangered Species

FEATURE: ENDANGERED SPECIES Conservation Status of Imperiled North American Freshwater and Diadromous Fishes ABSTRACT: This is the third compilation of imperiled (i.e., endangered, threatened, vulnerable) plus extinct freshwater and diadromous fishes of North America prepared by the American Fisheries Society’s Endangered Species Committee. Since the last revision in 1989, imperilment of inland fishes has increased substantially. This list includes 700 extant taxa representing 133 genera and 36 families, a 92% increase over the 364 listed in 1989. The increase reflects the addition of distinct populations, previously non-imperiled fishes, and recently described or discovered taxa. Approximately 39% of described fish species of the continent are imperiled. There are 230 vulnerable, 190 threatened, and 280 endangered extant taxa, and 61 taxa presumed extinct or extirpated from nature. Of those that were imperiled in 1989, most (89%) are the same or worse in conservation status; only 6% have improved in status, and 5% were delisted for various reasons. Habitat degradation and nonindigenous species are the main threats to at-risk fishes, many of which are restricted to small ranges. Documenting the diversity and status of rare fishes is a critical step in identifying and implementing appropriate actions necessary for their protection and management. Howard L. Jelks, Frank McCormick, Stephen J. Walsh, Joseph S. Nelson, Noel M. Burkhead, Steven P. Platania, Salvador Contreras-Balderas, Brady A. Porter, Edmundo Díaz-Pardo, Claude B. Renaud, Dean A. Hendrickson, Juan Jacobo Schmitter-Soto, John Lyons, Eric B. Taylor, and Nicholas E. Mandrak, Melvin L. Warren, Jr. Jelks, Walsh, and Burkhead are research McCormick is a biologist with the biologists with the U.S. -

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(S): Noel M

Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 Author(s): Noel M. Burkhead Source: BioScience, 62(9):798-808. 2012. Published By: American Institute of Biological Sciences URL: http://www.bioone.org/doi/full/10.1525/bio.2012.62.9.5 BioOne (www.bioone.org) is a nonprofit, online aggregation of core research in the biological, ecological, and environmental sciences. BioOne provides a sustainable online platform for over 170 journals and books published by nonprofit societies, associations, museums, institutions, and presses. Your use of this PDF, the BioOne Web site, and all posted and associated content indicates your acceptance of BioOne’s Terms of Use, available at www.bioone.org/page/terms_of_use. Usage of BioOne content is strictly limited to personal, educational, and non-commercial use. Commercial inquiries or rights and permissions requests should be directed to the individual publisher as copyright holder. BioOne sees sustainable scholarly publishing as an inherently collaborative enterprise connecting authors, nonprofit publishers, academic institutions, research libraries, and research funders in the common goal of maximizing access to critical research. Articles Extinction Rates in North American Freshwater Fishes, 1900–2010 NOEL M. BURKHEAD Widespread evidence shows that the modern rates of extinction in many plants and animals exceed background rates in the fossil record. In the present article, I investigate this issue with regard to North American freshwater fishes. From 1898 to 2006, 57 taxa became extinct, and three distinct populations were extirpated from the continent. Since 1989, the numbers of extinct North American fishes have increased by 25%. From the end of the nineteenth century to the present, modern extinctions varied by decade but significantly increased after 1950 (post-1950s mean = 7.5 extinct taxa per decade). -

Comparison of Electrofishing Fish Surveys and Angler Observation on Three Reaches of the Upper Rio Grande Barry Weinstock

University of New Mexico UNM Digital Repository Water Resources Professional Project Reports Water Resources 2014 Comparison of Electrofishing Fish Surveys and Angler Observation on Three Reaches of the Upper Rio Grande Barry Weinstock Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/wr_sp Recommended Citation Weinstock, Barry. "Comparison of Electrofishing Fish Surveys and Angler Observation on Three Reaches of the Upper Rio Grande." (2014). https://digitalrepository.unm.edu/wr_sp/107 This Presentation is brought to you for free and open access by the Water Resources at UNM Digital Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Water Resources Professional Project Reports by an authorized administrator of UNM Digital Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Comparison of Electrofishing Fish Surveys and Angler Observation on Three Reaches of the Upper Rio Grande by Barry Weinstock Committee Dr. Bruce M. Thomson, Chair Dr. William M. Fleming Eric Frey A Professional Project Proposal Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degrees of Master of Water Resources, Water Resources Program and Master Community and Regional Planning, School of Architecture and Planning The University of New Mexico Albuquerque, New Mexico July 2014 i Committee Approval The Master of Water Resources and Master of Community and Regional Planning Professional Project Report of Barry Weinstock, entitled Comparison of Electrofishing Fish Surveys and Angler Observation on Three Reaches of the Upper Rio Grande, is approved by the committee: ________________________________________ ____________________ Chair Date ________________________________________ ____________________ ________________________________________ ____________________ ________________________________________ ____________________ ________________________________________ ____________________ i Acknowledgements I would like to thank my committee. Dr. Bruce Thomson and Dr.