Downloads/List-Of-Acceptable-Commercial-Primers- Probes.Pdf 87

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Bsl-2 Enhanced Work Practices for Specimen Processing and Cell Culture

BSL-2 ENHANCED WORK PRACTICES FOR SPECIMEN PROCESSING AND CELL CULTURE [email protected] 4/1/21 [CA] Sleeve covers should be used for coats with uncuffed sleeves • BSC should be certified annually and have a current certification sticker attached. Ensure that the samples are coded and labeled in a way that identifies their contents to the laboratory. The lab must implement an easy to understand tracking system to discriminate live from inactive material. This could be different colored tubes, colored labels (“cryodots”), colored sharpies etc. Maintain your inventory in a secure manner. 1 • Prepare fresh 10% bleach in water each day. Label with date • Add concentrated bleach to aspiration flasks before use (add 10% of final volume). • Media should turn pink to clear on contact Do not use this waste bag for items that can puncture a red bag (e.g. pipette tips, serological pipettes) •A plastic beaker can also be used instead and can also be used to collect pipette tips and serological pipettes. Rinse these once with bleach in beaker •Dispose by decanting 10% bleach down drain •Pipette tips and serological pipettes are transferred to a sharps container Content generously shared by Yale University EH&S The Association for Biosafety and Biosecurity Considerations for Handling Potential SARS-CoV-2 Samples BSL2 BSL2 with BSL3 practices BSL3 ● Whole blood, serum and urine ● Aliquoting and/or diluting specimens ● Virus isolation/propagation in cell culture and initial ● Synthetic messenger RNA-based or recombinant protein-based products ● Inoculating -

Control Practices for Delivering Direct Student Support Services

MINNESOTA DEPARTMENT OF HEALTH Recommendations for Infection Prevention and Control Practices for Delivering Direct Student Support Services 5 / 2 7 /2021 This guidance provides strongly recommended practices to school staff on the use of protective equipment to reduce the risk of COVID-19 and other communicable disease transmission when delivering direct student support services that require close, prolonged contact. This guidance applies to services delivered in kindergarten through grade 12 special and general education, pre-kindergarten programs, birth to three-part C under IDEA, and school-based child care programs. References: . CDC: Information for School Nurses and Other Healthcare Personnel (HCP) Working in Schools and Child Care Settings (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/community/schools-childcare/school- nurses-hcp.html) . CDC: Interim Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations for Healthcare Personnel During the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) Pandemic (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019- ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html) . CDC: Updated Healthcare Infection Prevention and Control Recommendations in Response to COVID-19 Vaccination (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-after- vaccination.html) . CDC: Guidance for Direct Service Providers (www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/need-extra- precautions/direct-service-providers.html) . AAP: COVID-19 Guidance for Safe Schools (services.aap.org/en/pages/2019-novel-coronavirus- covid-19-infections/clinical-guidance/covid-19-planning-considerations-return-to-in-person- education-in-schools/) 1 of 13 RECOMMENDATIONS FOR INFECTION PREVENTION AND CONTROL PRACTICES FOR DELIVERING DIRECT STUDENT SUPPORT SERVICES Basic principles of infection control Face mask recommendations The following measures are strongly recommended when direct student support services are being provided to a student: . -

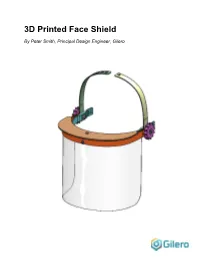

3D Printed Face Shield by Peter Smith, Principal Design Engineer, Gilero

3D Printed Face Shield By Peter Smith, Principal Design Engineer, Gilero This face shield design is based on an open source design by HanochH on Thingiverse. Changes were to make the design more robust. This design uses a number of 3D printed parts. The prototype was printed in PETG on a Fusion3. It also uses the following: • One (1) 12” x 7” sheet of PET clear film, 0.010 – 0.020” thick (or a cut up 2L soda bottle) • Two (2) ¼-20 x 5/8” long Hex Head Screws (with 7/16” across the flats of the hex head) • Two (2) ¼-20 Hex Nuts (with 7/16” across the flats) • Two (2) #6 x ½” long button head sheet metal screws • Ten inches of ¼” braided elastic or similar The above are commonly available in any hardware store or from online vendors such as McMaster-Carr: www.mcmaster.com Tools required for assembly: • Phillips screwdriver (#1 or #2) • Box cutter or sharp knife • Pair of household scissors Step 1. Print all parts using the supplied STL files. Note that 2 copies of the thumbnut will be needed. Press the nuts into the thumbnut printed parts. Press the Hex Head Screws into the recesses in the blue part shown and through the holes in the other parts as shown. Screw the assembled thumbnuts onto the Hex Head Screws to hold the assembly together. Step 2. Secure the cap with one of the #6 sheet metal screws. Step 3. Slip the visor into the gap in the orange part shown until it butts up to the cap. -

OHA's Mask, Face Covering, and Face Shield Requirements for Health Care

OFFICE OF THE DIRECTOR Kate Brown, Governor 500 Summer St NE E20 Salem OR 97301 Voice: 503-947-2340 Date: June 30,2021 Fax: 503-947-2341 Mask, Face Covering, and Face Shield Requirements for Health Care Offices While the Governor has rescinded many of the Executive Orders, the declaration of emergency remains in effect and masks are still required in health care settings. See Executive Order 21-15. In addition, health care offices must continue to follow all applicable state and federal regulatory requirements related to masking, including Oregon-OSHA rules addressing COVID-19 workplace risks. Authority: ORS 433.441, ORS 433.443, ORS 431A.010 and ORS 431A.015 Applicability: These requirements apply to: • All health care personnel in health care offices, as defined below. • All patients and visitors in health care offices, as defined below. Definitions: • “Face covering” means a cloth, polypropylene, paper or other face covering that covers the nose and the mouth and that rests snugly above the nose, below the mouth, and on the sides of the face. • “Face mask” means a medical grade mask. • “Face shield” means a clear plastic shield that covers the forehead, extends below the chin, and wraps around the sides of the face. • “Healthcare Personnel (HCP)” means all paid and unpaid persons serving in healthcare offices who have the potential for direct or indirect exposure to patients or infectious materials, including body substances (e.g., blood, tissue, and specific body fluids); contaminated medical supplies, devices, and equipment; contaminated -

The Challenge of Performing Mastoidectomy Using The

The challenge of performing mastoidectomy using the operating microscope with COVID-19 personal protective equipment (PPE) Philip Clamp1 and Stephen Broomfield1 1University Hospitals Bristol and Weston NHS Foundation Trust May 19, 2020 Abstract Objective: As an aerosol generating procedure (AGP), mastoidectomy in the COVID-19 era requires healthcare workers to wear personal protective equipment (PPE); UK guidelines recommend an FFP-3 mask and full-face visor. The aim of this study was to examine the effect of wearing PPE on the view achieved using the operating microscope. Methods: Using the operating microscope, ENT surgeons were asked to view a target so that it filled the entire operating field. The distance between the surgeon's eye and the microscope was recorded and subsequently measured with the surgeon wearing a range of PPE. In each PPE condition, surgeons scored the visibility of the target; scores were used to calculate the visible area of the surgical field. Results: Eleven surgeons took part, generating 51 eye-microscope and target-view scores. Distance from the eye to the microscope inversely correlated with diameter and area visible (Pearson correlation coefficient -0.983 and -0.894 respectively; p<0.001). Use of PPE increased the eye-microscope distance and reduced the surgical view. The median area visible wearing the FFP-3 mask and full-face visor was 4% (range 4 { 16%). Conclusion: PPE consisting of an FFP-3 mask and full-face visor is incompatible with use of the operating microscope, with less than 10% of the surgical field visible in most cases. Solutions that allow for concurrent use of the operating microscope and drill during mastoid surgery are urgently required so that surgeons are adequately protected from COVID-19 transmission. -

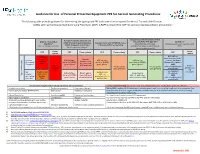

Guidance for Use of PPE for Aerosol Generating Procedures (PDF)

Guidance for Use of Personal Protective Equipment PPE for Aerosol Generating Procedures The following table provides guidance for determining the appropriate PPE and room criteria required for Aerosol Transmissible Diseases 1 (ATDs) when performing Aerosol Generating Procedures (AGP). A PAPR is required for AGP for patients requiring airborne precautions. Droplet transmitted infections2 that Has signs/symptoms consistent with Airborne transmitted are part of the ATD Standard All Others5 COVID-19 and undergoing evaluation, Asymptomatic with COVID-19 status infections2 (e.g. influenza, adenovirus) (Including patients with negative COVID COVID-19 exposed, or confirmed unknown and/or test pending (e.g. TB, measles, varicella) excludes RSV, rhinovirus, parainfluenza, tests) (Novel respiratory isolation)3 human metapneumovirus Room 3 Room PPE PPE Room criteria PPE Room criteria PPE Room criteria PPE criteria criteria N95 with eye PAPR and 6 protection (or PAPR) refer to Airborne Aerosol N95 with face N95 with face N95 with eye recommended plus isolation Isolation room Generating shield (or PAPR), shield (or PAPR), protection (or PAPR), Standard Precautions table for continuous 4 4 Procedure gown, gloves gown, gloves gown, gloves AND Airborne AGP preferred Private Private patient Private patient refer to isolation table Isolation patient room room preferred room preferred as applicable room not Use Standard 7 Not PAPR or N95 Surgical mask necessary N95 with face Private patient Surgical mask Precautions aerosol and refer to with eye Type of -

Face Shields; Health Care Personnel; Hospital Purchasing Departments and Distributors; And, Any Other Stakeholders

April 13, 2020 To: Manufacturers of Face Shields; Health Care Personnel; Hospital Purchasing Departments and Distributors; and, Any Other Stakeholders On April 9, 2020, the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) issued an Emergency Use Authorization (EUA) in response to concerns relating to insufficient supply and availability of face shields1 for use by health care personnel (HCP) as personal protective equipment (PPE) in healthcare settings in accordance with CDC recommendations to cover the front and sides of the face and provide barrier protection during the Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. On April 13, 2020, in response to questions from stakeholders regarding the authorization process, and having concluded that revising the April 9, 2020, EUA is appropriate to protect the public health or safety under section 564(g)(2)(c) of the Act (21 U.S.C. 360bbb-3(g)(2)(c)), FDA is reissuing the April 9, 2020, letter in its entirety with an amendment incorporated to clarify that this letter of authorization, as posted and publicly announced on FDA’s website at https://www.fda.gov/medical-devices/emergency-situations-medical-devices/emergency-use- authorizations#covid19ppe, serves as face shield manufacturers’ notification of authorization. As stated in the April 9, 2020 letter, manufacturers of authorized face shields do not need to take any action, other than complying with the Conditions of Authorization (Section IV) in this letter of authorization, to be an authorized face shield under this EUA if the face shield is within -

Face Shield and Headgear (FSU1610HB3) SOLUTIONS for MEDICAL PROVIDERS and FIRST RESPONDERS

Face Shield and Headgear (FSU1610HB3) SOLUTIONS FOR MEDICAL PROVIDERS AND FIRST RESPONDERS FEATURES • Shields eyes and face from fluid, sprays and splashes • Easy to put on and take off when time is critical • Transparent shield with headgear, strap and optional foam strip • For use with goggles or glasses • Flexible headgear contours to forehead • With anti-fog • Option for replacement shields for head gear • Disposable or reusable* • Shipped in individual poly bags • Lightweight • Non-sterile SPECS • FSU1610HB3 (unassembled kit) • Shield thickness: 15 mil/0.015 in • Shield dimensions: 16 in W x 9.45 in H • Shield material: PET • Headgear material: Injection-molded polypropylene • Foam material: Polyurethane Foam • Strap material: Synthetic (Non Latex) Polyisoprene • Manufactured in North America For more information contact [email protected] PLEASE NOTE • This product has NOT been FDA cleared or approved. • This product has been authorized by FDA under an Emergency Use Authorization for use by healthcare providers as personal protective equipment. • This product is only authorized for the duration of the declaration that circumstances justifying the authorization of emergency use under Section 564(b)(1) of the Act, 21 USC 360bbb-3(b)(1) unless the authorization is terminated or revoked sooner. CAUTION • This product is NOT intended for use in presence of high intensity light source or flammable gas. • This product is NOT sterilized. • Use of this face shield alone will NOT prevent infection from microbes or viruses. Shown with foam added *Cleaning/disinfecting instructions listed on reverse side of document Face Shield and Headgear CLEANING AND DISINFECTING INSTRUCTIONS • To clean and disinfect, use a Health Canada authorized hard-surface disinfectant. -

(IBRDSC) Policy: Maintenance of Laboratory Equipment

LSU Inter-Institutional Biological and Recombinant DNA Safety Committee (IBRDSC) Policy: Maintenance of Laboratory Equipment Adopted April 26, 2012 Properly functioning laboratory equipment is a critical component of good laboratory practice and safety. Each laboratory should have equipment management policies which include regular inspections and comprehensive equipment maintenance strategies. Many of the accidents that occur in the laboratory can be attributed to improper use or maintenance of laboratory equipment. (Autoclave use and validation is a separate policy.) Equipment Examples: Microplate Reader, Microplate Washer, pH Meter, Balances, Water Bath, Water Distiller, Dilutor, Dispenser, Spectrophotometer, Autoclave, Drying Oven, Incubator, Microscope, Pipettes, Stirring Heating Plate, Refrigerators, Freezers, Chemistry Analyzers, Colorimeters, Biological Safety Cabinets, Chemical Fume Hoods, Centrifuges, Biological Safety Cabinets Biological safety cabinets must be certified at least annually (BSL-3 laboratories bi-annually) according to the National Sanitation Foundation Standard/American National Standard 49 (NSF/ANSI 49), which is the accepted standard for the biological safety cabinet industry. Testing must be performed to verify air flows, HEPA filter integrity, containment of contaminated cabinet air, and that the cabinet is safe to operate regarding other cabinet operational features. Whenever biological safety cabinets are moved, internal repairs are to be made, or when filters are to be replaced, the cabinet must be gaseous decontaminated. It also must be recertified before use. LSU requires that certification be done by third party firms and is the responsibility of the user. Types of Biological Safety Cabinets http://www.cdc.gov/biosafety/publications/bmbl5/BMBL5_appendixA.p df Class I: Protection for the operator, but no product protection. Air flow, at a minimum inward face velocity of 75 linear feet per minute (lfpm), directed through the front opening, across the work area and out through the HEPA filter on top. -

Bio-Rad Protein Assay

LIT33C 8/31/98 02:25 PM Page a Bio-Rad Protein Assay For Technical Service Call Your Local Bio-Rad Office or in the U.S. Call 1-800-4BIORAD (1-800-424-6723) LIT33C 8/31/98 02:25 PM Page b Table of Contents Section 1 Introduction..................................................................... 1 1.1 Principle ..................................................................................... 1 1.2 Product Description.................................................................... 3 1.3 Materials Required but Not Supplied......................................... 3 Section 2 Instructions...................................................................... 4 2.1 Reconstituting the Standard ....................................................... 4 2.2 Standard Procedure .................................................................... 4 2.3 Microassay Procedure................................................................ 5 2.4 Microtiter Plate Protocols .......................................................... 6 Section 3 Common Questions......................................................... 8 Section 4 Troubleshooting Guide ................................................... 12 Section 5 Ordering Information..................................................... 13 Section 6 Safety Information .......................................................... 14 Section 7 References........................................................................ 24 LIT33C 8/31/98 02:25 PM Page 1 Section 1 Introduction The Bio-Rad Protein -

Safety Apparel & Equipment

SAFETY 20,000 PSI SAFETY APPAREL & EQUIPMENT SAFETY. The one word every organization places at the top of the list when thinking about an employee. Jetstream understands the importance of conducting a safe environment when working in any high pressure waterblasting application. From personal protective equipment (PPE) to caution tape and signage, Jetstream provides a complete line of safety products to ensure a well protected jobsite and operator safety. Products included in this section: Visual Safety System • Jetstream’s pioneered Visual Safety System • Safety protection through color coding of parts • Guns, Foot Guns, Hoses, Lances, Fittings and Decals Safety Shrouds • Standard Waterblasting Safety Shrouds • TST Hose Shrouds • TST Hose Connection Covers • Covered Safety Whips Flex Lance Safety • Hand-Held Lance Grip & Accessories • Pipe and Tube Cleaning Exit Safety Devices Personal Protective Equipment (PPE) • TurtleSkin® WaterArmor • TST® Waterjet Protection SAFETY Safety Accessories • Safety Glasses, Goggles, Boots and Gloves • Face Shield, Hard Hats, and Ear Protection • Protection Suits Safety Tape, Signs and Decals Safety Hose Checks • Nylon • Stainless Steel H-1 US & Canada: 800-231-8192 or 832-590-1300 SAFETY 20,000 PSI VISUAL SAFETY SYSTEM PROTECT YOUR WORKERS AND THE WATERBLASTING EQUIPMENT WITH JETSTREAM’S VISUAL SAFETY SYSTEM. Ensuring the operator is using the correct equipment is now identifiable from a distance. Jetstream’s Visual Safety System uses highly visible and color-matched decals and additional makers to clearly show waterblast components in use are correctly and safely suited to current pump pressures. Jetstream is now following the WJTA recommended colors to visually identify the pressure being used on a job site: • 10,000 psi – YELLOW • 15,000 psi – GREEN • 20,000 psi – BLUE • 40,000 psi – ORANGE Hoses and Lances—Identifying a pressure of a supply hose and lance will now be easy. -

Download Cryopreservation of Cells: Freezing and Thawing

UNIVERSITY OF ROCHESTER MEDICAL CENTER Human Immunology Center Core Laboratory David H. Smith Center for Vaccine Biology and Immunology Aab Institute of Biomedical Sciences STANDARD OPERATING PROCEDURE: NUMBER HIC-1-0007.2 Date: 27-December-2006 Author: Sally A. Quataert Approved: Sally A. Quataert Title: Cryopreservation of cells: freezing and thawing Purpose and Scope: This procedure describes how to freeze and thaw mammalian cells in the Human Immunology Core Laboratory. Principle: Cells may be frozen at a slow controlled rate of minus one degree Celsius per minute in cryoprotectant medium containing 10% dimethylsulfoxide (DMSO). Cells are allowed to absorb DMSO into cell membranes for 15 minutes. The DMSO acts to prevent ice crystal formation during the slow freezing process, maintaining cell viability. Some cell types such as PBMC may be stored short term (less than one week) at -800 C or long term in a liquid nitrogen freezer. For maximum recovery and viability upon thawing, cells should be healthy with greater than 90% viable prior to freezing. Successful cell recovery from the frozen state requires rapid thawing of the cells followed by immediate removal of cryoprotectant medium from the cells. References: Recommendations for Prevention of HIV Transmission in Health-Care Settings: Universal Blood and Body Fluid Precautions Guideline CDC 1987 CDC Biosafety in Microbiological and Biomedical Laboratories 4th Ed U.S.H&HS, Public Heath Service Safety: Personnel will adhere to safe work processes outlined in U.S. Public Health Universal