VENUS in FUR a Roman Polanski Film

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

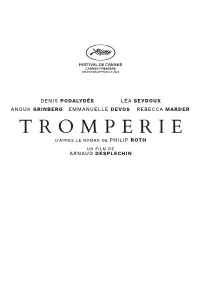

Tromperie D’Après Le Roman De Philip Roth

DENIS PODALYDÈS LÉA SEYDOUX ANOUK GRINBERG EMMANUELLE DEVOS REBECCA MARDER TROMPERIE D’APRÈS LE ROMAN DE PHILIP ROTH UN FILM DE ARNAUD DESPLECHIN WHY NOT PRODUCTIONS PRÉSENTE DENIS PODALYDÈS LÉA SEYDOUX ANOUK GRINBERG EMMANUELLE DEVOS REBECCA MARDER TROMPERIE D’APRÈS LE ROMAN DE PHILIP ROTH UN FILM DE ARNAUD DESPLECHIN 1h45 – France – 2021 – Scope – 5.1 AU CINÉMA LE 8 DÉCEMBRE DISTRIBUTION RELATIONS PRESSE Marie Queysanne 5, rue Darcet Tél. : 01 42 77 03 63 75017 Paris [email protected] Tél. : 01 44 69 59 59 [email protected] www.le-pacte.com Matériel presse téléchargeable sur www.le-pacte.com « La seule chose que je puisse avancer sans hésiter, c’est que je n’ai pas de « moi » et que je refuse de faire les frais de cette farce. […] M’en tient lieu tout un éventail de rôles que je peux jouer, et pas seulement le mien ; j’ai intériorisé toute une troupe, un stock de scènes et de rôles […] qui forment mon répertoire. Mais je n’ai certes aucun « moi » indépendant de mes efforts – autant de postures artistiques – pour en avoir un. Du reste, je n’en veux pas. Je suis un théâtre, et rien d’autre qu’un théâtre. » Philip Roth, La Contrevie (The Counterlife), 1986, éditions Gallimard, traduction de Josée Kamoun (2004) 3 SYNOPSIS Londres - 1987. Philip est un écrivain américain célèbre exilé à Londres. Sa maîtresse vient régulièrement le retrouver dans son bureau, qui est le refuge des deux amants. Ils y font l’amour, se disputent, se retrouvent et parlent des heures durant ; des femmes qui jalonnent sa vie, de sexe, d’antisémitisme, de littérature, et de fidélité à soi-même… 4 Entretien avec ARNAUD DESPLECHIN Au dos de ses images, Tromperie semble inscrire une profession de foi dans les pouvoirs de la fiction en général et dans ceux du cinéma en particulier… Ce film relève, en effet, de la profession de foi. -

Berlin 2021 Market Screenings

BERLIN 2021 MARKET SCREENINGS GALLANT INDIES Indes galantes By Philippe Béziat ("BECOMING TRAVIATA") Based on Jean-Philippe Rameau’s opera-ballet that was directed by Clément Cogitore for the Opéra National de Paris. This is a premiere for 30 dancers of hip-hop, krump, break, voguing… A first for the Director Clément Cogitore and for the choreographer Bintou Dembélé. And a first for the Paris’ Opera Bastille. By bringing together urban dance and opera singing, they reinvent Jean-Philippe Rameau's baroque masterpiece, Les Indes Galantes. From rehearsals to public performances, it is a human adventure and a meeting of political realities that we follow: can a new generation of artists storm the Bastille today? FRENCH - DOCUMENTARY - 108 MN Production : LES FILMS PELLEAS (FRANCE), ARTE FRANCE CINEMA (FRANCE) Territories sold : France MARKET SCREENING Monday 1st 5.40 PM (local time) Virtual Cinema 14 Wednesday 3rd 9.05 AM (local time) Virtual Cinema 7 MARKET SCREENINGS I HAVE BEEN WAITING FOR YOU c’est toi que j’attendais By Stéphanie Pillonca ("FLEUR DE TONNERRE") "They are couples like no others: couples who cannot bear children in a biological way and decide to go through adoption. From this decision and the actual meeting with the child, we’ll experience with them the sufferings, doubts, hopes and finally the joys of this life- changing journey. With throughout the film, this underlying question: What makes a family? How does this unfailing bond between a child and his/her parent form?" Stéphanie Pillonca FRENCH - DOCUMENTARY - 87 MN Production: -

Feature Films

NOMINATIONS AND AWARDS IN OTHER CATEGORIES FOR FOREIGN LANGUAGE (NON-ENGLISH) FEATURE FILMS [Updated thru 88th Awards (2/16)] [* indicates win] [FLF = Foreign Language Film category] NOTE: This document compiles statistics for foreign language (non-English) feature films (including documentaries) with nominations and awards in categories other than Foreign Language Film. A film's eligibility for and/or nomination in the Foreign Language Film category is not required for inclusion here. Award Category Noms Awards Actor – Leading Role ......................... 9 ........................... 1 Actress – Leading Role .................... 17 ........................... 2 Actress – Supporting Role .................. 1 ........................... 0 Animated Feature Film ....................... 8 ........................... 0 Art Direction .................................... 19 ........................... 3 Cinematography ............................... 19 ........................... 4 Costume Design ............................... 28 ........................... 6 Directing ........................................... 28 ........................... 0 Documentary (Feature) ..................... 30 ........................... 2 Film Editing ........................................ 7 ........................... 1 Makeup ............................................... 9 ........................... 3 Music – Scoring ............................... 16 ........................... 4 Music – Song ...................................... 6 .......................... -

Space, Vision, Power, by Sean Carter and Klaus Dodds. Wallflower, 2014, 126 Pp

Alphaville: Journal of Film and Screen Media no. 21, 2021, pp. 228–234 DOI: https://doi.org/10.33178/alpha.21.19 International Politics and Film: Space, Vision, Power, by Sean Carter and Klaus Dodds. Wallflower, 2014, 126 pp. Juneko J. Robinson Once, there were comparatively few books that focused on the relationship between international politics and film. Happily, this is no longer the case. Sean Carter and Klaus Dodd’s International Politics and Film: Space, Vision, Power is an exciting addition to the growing body of literature on the political ontology of art and aesthetics. As scholars in geopolitics and human geography, their love for film is evident, as is their command of the interdisciplinary literature. Despite its brevity, this well-argued and thought-provoking book covers an impressive 102 films from around the world, albeit some in far greater detail than others. Still, despite its compactness, it is a satisfying read that will undoubtedly attract casual readers unfamiliar with scholarship in either discipline but with enough substance to delight specialists in both film and international relations. Carter and Dodds successfully bring international relations (IR) and critical geopolitics into closer alignment with visual studies in general and film studies in particular. Their thesis is simple: first, the traditional emphasis of IR on macro-level players such as heads of state, diplomats, the intelligence community, and intergovernmental organisations such as the United Nations have created a biased perception of what constitutes the practice of international politics. Second, this bias is problematic because concepts such as the state and the homeland, amongst others, are abstract entities whose ontological statuses do not exist apart from the practices of people. -

Film & Event Calendar

1 SAT 17 MON 21 FRI 25 TUE 29 SAT Events & Programs Film & Event Calendar 12:00 Event 4:00 Film 1:30 Film 11:00 Event 10:20 Family Gallery Sessions Tours for Fours: Art-Making Warm Up. MoMA PS1 Sympathy for The Keys of the #ArtSpeaks. Tours for Fours. Daily, 11:30 a.m. & 1:30 p.m. Materials the Devil. T1 Kingdom. T2 Museum galleries Education & 4:00 Film Museum galleries Saturdays & Sundays, Sep 15–30, Research Building See How They Fall. 7:00 Film 7:00 Film 4:30 Film 10:20–11:15 a.m. Join us for conversations and T2 An Evening with Dragonfly Eyes. T2 Dragonfly Eyes. T2 10:20 Family Education & Research Building activities that offer insightful and Yvonne Rainer. T2 A Closer Look for 7:00 Film 7:30 Film 7:00 Film unusual ways to engage with art. Look, listen, and share ideas TUE FRI MON SAT Kids. Education & A Self-Made Hero. 7:00 Film The Wind Will Carry Pig. T2 while you explore art through Research Building Limited to 25 participants T2 4 7 10 15 A Moment of Us. T1 movement, drawing, and more. 7:00 Film 1:30 Film 4:00 Film 10:20 Family Innocence. T1 4:00 Film WED Art Lab: Nature For kids age four and adult companions. SUN Dheepan. T2 Brigham Young. T2 This Can’t Happen Tours for Fours. SAT The Pear Tree. T2 Free tickets are distributed on a 26 Daily. Education & Research first-come, first-served basis at Here/High Tension. -

Communiqué De Presse

LE JURY DES LONGS MÉTRAGES 2019 La 26e édition du FESTIVAL INTERNATIONAL DU FILM FANTASTIQUE DE GÉRARDMER se déroulera du 30 janvier au 3 février 2019. Le Jury des Longs Métrages sera co-présidé par les réalisateurs, scénaristes, producteurs et comédiens français : BENOÎT DELÉPINE & GUSTAVE KERVERN © DR Les cinéastes Gustave Kervern et Benoit Delépine font leurs premières armes à la télévision, l’un pour « Le plein de Super », et l’autre pour « Les Guignols de l’info ». Le duo naît de leur rencontre sur les plateaux de l’émission « Groland », incarnation du vent de liberté qui soufflait alors sur Canal+. Fidèles à l’esprit contestataire de la chaîne, ils irriguent leurs réalisations d’une apparente désinvolture, faite d’improvisation et de surréalisme dès leur premier long-métrage Aaltra (2004). Dans leurs films suivants, Avida (2006), Louise Michel (2008), Mammuth (2010), Le Grand soir (2012), ils poursuivent leur vision du monde et mettent en scène des personnages marginaux, laissés pour compte: Yolande Moreau, Benoît Poelvoorde, Mathieu Kassovitz, Albert Dupontel, Gérard Depardieu, Bouli Lanners ou encore Isabelle Adjani se succèdent ainsi devant leur caméra, aux côtés de comédiens non professionnels. En 2014, ils collaborent avec Michel Houellebecq, écrivain lauréat du Prix Goncourt pour « La carte et le territoire » et personnage central sur lequel se construit leur film Near Death Experience. Ils retrouvent ensuite Gérard Depardieu et Benoît Poelvoorde pour leur road-movie Saint Amour (2016). Leur dernière réalisation I Feel Good, -

BORSALINO » 1970, De Jacques Deray, Avec Alain Delon, Jean-Paul 1 Belmondo

« BORSALINO » 1970, de Jacques Deray, avec Alain Delon, Jean-paul 1 Belmondo. Affiche de Ferracci. 60/90 « LA VACHE ET LE PRISONNIER » 1962, de Henri Verneuil, avec Fernandel 2 Affichette de M.Gourdon. 40/70 « DEMAIN EST UN AUTRE JOUR » 1951, de Leonide Moguy, avec Pier Angeli 3 Affichette de A.Ciriello. 40/70 « L’ARDENTE GITANE» 1956, de Nicholas Ray, avec Cornel Wilde, Jane Russel 4 Affiche de Bertrand -Columbia Films- 80/120 «UNE ESPECE DE GARCE » 1960, de Sidney Lumet, avec Sophia Loren, Tab Hunter. Affiche 5 de Roger Soubie 60/90 « DEUX OU TROIS CHOSES QUE JE SAIS D’ELLE» 1967, de Jean Luc Godard, avec Marina Vlady. Affichette de 6 Ferracci 120/160 «SANS PITIE» 1948, de Alberto Lattuada, avec Carla Del Poggio, John Kitzmille 7 Affiche de A.Ciriello - Lux Films- 80/120 « FERNANDEL » 1947, film de A.Toe Dessin de G.Eric 8 Les Films Roger Richebé 80/120 «LE RETOUR DE MONTE-CRISTO» 1946, de Henry Levin, avec Louis Hayward, Barbara Britton 9 Affiche de H.F. -Columbia Films- 140/180 «BOAT PEOPLE » (Passeport pour l’Enfer) 1982, de Ann Hui 10 Affichette de Roland Topor 60/90 «UN HOMME ET UNE FEMME» 1966, de Claude Lelouch, avec Anouk Aimée, Jean-Louis Trintignant 11 Affichette les Films13 80/120 «LE BOSSU DE ROME » 1960, de Carlo Lizzani, avec Gérard Blain, Pier Paolo Pasolini, Anna Maria Ferrero 12 Affiche de Grinsson 60/90 «LES CHEVALIERS TEUTONIQUES » 1961, de Alexandre Ford 13 Affiche de Jean Mascii -Athos Films- 40/70 «A TOUT CASSER» 1968, de John Berry, avec Eddie Constantine, Johnny Halliday, 14 Catherine Allegret. -

MY KING (MON ROI) a Film by Maïwenn

LES PRODUCTIONS DU TRESOR PRESENTS MY KING (MON ROI) A film by Maïwenn “Bercot is heartbreaking, and Cassel has never been better… it’s clear that Maïwenn has something to say — and a clear, strong style with which to express it.” – Peter Debruge, Variety France / 2015 / Drama, Romance / French 125 min / 2.40:1 / Stereo and 5.1 Surround Sound Opens in New York on August 12 at Lincoln Plaza Cinemas Opens in Los Angeles on August 26 at Laemmle Royal New York Press Contacts: Ryan Werner | Cinetic | (212) 204-7951 | [email protected] Emilie Spiegel | Cinetic | (646) 230-6847 | [email protected] Los Angeles Press Contact: Sasha Berman | Shotwell Media | (310) 450-5571 | [email protected] Film Movement Contacts: Genevieve Villaflor | PR & Promotion | (212) 941-7744 x215 | [email protected] Clemence Taillandier | Theatrical | (212) 941-7744 x301 | [email protected] SYNOPSIS Tony (Emmanuelle Bercot) is admitted to a rehabilitation center after a serious ski accident. Dependent on the medical staff and pain relievers, she takes time to look back on the turbulent ten-year relationship she experienced with Georgio (Vincent Cassel). Why did they love each other? Who is this man whom she loved so deeply? How did she allow herself to submit to this suffocating and destructive passion? For Tony, a difficult process of healing is in front of her, physical work which may finally set her free. LOGLINE Acclaimed auteur Maïwenn’s magnum opus about the real and metaphysical pain endured by a woman (Emmanuelle Bercot) who struggles to leave a destructive co-dependent relationship with a charming, yet extremely self-centered lothario (Vincent Cassel). -

All-Celluloid Homage to a Diva of the Italian Cinema

ALL-CELLULOID HOMAGE TO A DIVA OF THE ITALIAN CINEMA Sept. 24, 2016 / Castro Theatre / San Francisco / CinemaItaliaSF.com ROMA CITTÀ APERTA (ROME OPEN CITY) Sat. September 24, 2016 1:00 PM 35mm Film Projection (100 mins. 1945. BW. Italy. In Italian, German, and Latin with English subtitles) Winner of the 1946 Festival de Cannes Grand Prize, Rome Open City was Roberto Rossel- lini’s revelation – a harrowing drama about the Nazi occupation of Rome and the brave few who struggled against it. Told with melodramatic flair and starring Aldo Fabrizi as a priest helping the partisan cause and Anna Magnani in her breakthrough role as Pina, the fiancée of a resistance member, Rome Open City is a shockingly authentic experi- ence, conceived and directed amid the ruin of World War II, with immediacy in every frame. Marking a watershed moment in Italian cinema, this galvanic work garnered awards around the globe and left the beginnings of a new film movement in its wake. Directed by Roberto Rossellini. Written by Sergio Amidei and Federico Fellini. Photo- graphed by Ubaldo Arata. Starring Anna Magnani and Aldo Fabrizi. Print Source: Istituto Luce-Cinecittá S.r.L. BELLISSIMA Sat. September 24, 2016 3:00 PM 35mm Film Projection (115 mins. 1951. BW. Italy. In Italian with English subtitles) Bellissima centers on a working-class mother in Rome, Maddalena (Anna Magnani), who drags her daughter (Tina Apicella) to Cinecittà to attend an audition for a new film by Alessandro Blasetti. Maddalena is a stage mother who loves movies and whose efforts to promote her daughter grow increasingly frenzied. -

Download Detailseite

Wettbewerb/IFB 2005 LES MOTS BLEUS WORTE IN BLAU WORDS IN BLUE Regie: Alain Corneau Frankreich 2004 Darsteller Clara Sylvie Testud Länge 114 Min. Vincent Sergi Lopez Format 35 mm, 1:1.85 Anna Camille Gauthier Farbe Muriel Mar Sodupe Claras Ehemann Cédric Chevalme Stabliste Annas Lehrerin Isabelle Petit-Jacques Buch Alain Corneau Vincents erste Dominique Mainard, Freundin Prune Lichtle nach dem Roman Vincents zweite „Leur histoire“ von Freundin Cécile Bois Dominique Mainard Baba Esther Gorintin Kamera Yves Angelo Muriels Tochter Gabrielle Lopes- Schnitt Thierry Derocles Benites Ton Pierre Gamet Muriels Sohn Louis Pottier-Arniaud Mischung Gérard Lamps Clara als Kind Clarisse Baffier Musik Christophe Claras Mutter Niki Zischka Jean-Michel Jarre Claras Vater Laurent Le Doyen Ausstattung Solange Zeitoun Claras Lehrerin Geneviève Yeuillaz Kostüm Julie Mallard Maske Sophie Benaiche Camille Gauthier Regieassistenz Vincent Trintignant Casting Gérard Moulevrier Pascale Beraud WORTE IN BLAU Produktionsltg. Frédéric Blum Anna ist ein kleines Mädchen von sechs Jahren, das sich weigert zu sprechen. Produzenten Michèle Petin Clara, ihre Mutter, wollte niemals lesen oder schreiben lernen. Einsam und Laurent Petin getrennt von der Welt betrachtet Anna ihre Mutter dabei, wie sie etwas in Co-Produktion France 3 Cinéma, ihre Taschen stopft oder wie sie etwas in den Saum ihrer Ärmel einnäht. Es Paris sind kleine Notizzettel, auf die Clara sich ihre Adresse hat schreiben lassen Produktion oder die Titel jener Bücher, die die Kleine so liebt, oder die Rezepte ihrer ARP liebsten Kuchen oder die Strophen ihrer Wiegenlieder. Denn es könnte pas- 13, rue Jean Mermoz sieren, dass sie sich für immer verlieren. Diese Notizzettel sind die einzige F-75908 Paris Wegzehrung, mit der das Kind versorgt ist, als es in die Schule für Taub- Tel.: 1-56 69 26 00 Fax: 1-45 63 83 37 stumme kommt. -

Festival Schedule

T H E n OR T HWEST FILM CE n TER / p ORTL a n D a R T M US E U M p RESE n TS 3 3 R D p ortl a n D I n ter n a tio n a L film festi v a L S p O n SORED BY: THE OREGO n I a n / R E G a L C I n EM a S F E BR U a R Y 1 1 – 2 7 , 2 0 1 0 WELCOME Welcome to the Northwest Film Center’s 33rd annual showcase of new world cinema. Like our Northwest Film & Video Festival, which celebrates the unique visions of artists in our community, PIFF seeks to engage, educate, entertain and challenge. We invite you to explore and celebrate not only the art of film, but also the world around you. It is said that film is a universal language—able to transcend geographic, political and cultural boundaries in a singular fashion. In the spirit of Robert Louis Stevenson’s famous observation, “There are no foreign lands. It is the traveler who is foreign,” this year’s films allow us to discover what unites rather than what divides. The Festival also unites our community, bringing together culturally diverse audiences, a remarkable cross-section of cinematic voices, public and private funders of the arts, corporate sponsors and global film industry members. This fabulous ecology makes the event possible, and we wish our credits at the back of the program could better convey our deep appreci- ation of all who help make the Festival happen. -

Film Education (Levan Koghuashvili, Maia Gugunava, Tato Kotetishvili) 139 1001 Ingredients for Making Films from Nana Jorjadze 146

~ editors letter ~ The year of 2015 started with our becoming members of the Creative Europe, while by the end of the year, with the purpose of supporting the cinema industry, Geor- gian government introduced a cash rebate system, we have been working on since 2009. I believe both of these initiatives will make a huge contribution to the develop- ment of our industry. 1 In 2016, movies of different genres will be released. It is notable that three feature films among those are directed by women. Projects we are currently working on are very important. We have announced new types of competitions on script development, including comedy and children’s movies, adaptation of Georgian prose of the 21st century, scripts dedicated to the 100th anniver- sary of Georgia’s independence, and animation. Winners are given long- term work- shops by European script doctors, so 2016 will be dedicated to the script development. The young generation has become active in the field: we had premieres of six short films and a short film by Data Pirtskhalava “Father” was the winner of the main prize in this category at Locarno International Film Festival. Other films – “Ogasavara”, “Fa- ther”, “Exit”, “Preparation”, “The First Day” – are also participating at different festivals. Masters of Georgian cinema are also making films side-by-side with the young genera- tion. I have to mention a film by Rezo Esadze “Day as a Month” with its extraordinary nar- rative structure and visualaspect, which will take its noteworthy place in our film collection. One of the most important goals this year will be to return Georgian cinema heritage from archives in Moscow and design a suitable storage facility for it.