1–5 Rediscovery in Singapore of Calamus Densiflorus Becc

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

An Annotated Checklist of the Angiospermic Flora of Rajkandi Reserve Forest of Moulvibazar, Bangladesh

Bangladesh J. Plant Taxon. 25(2): 187-207, 2018 (December) © 2018 Bangladesh Association of Plant Taxonomists AN ANNOTATED CHECKLIST OF THE ANGIOSPERMIC FLORA OF RAJKANDI RESERVE FOREST OF MOULVIBAZAR, BANGLADESH 1 2 A.K.M. KAMRUL HAQUE , SALEH AHAMMAD KHAN, SARDER NASIR UDDIN AND SHAYLA SHARMIN SHETU Department of Botany, Jahangirnagar University, Savar, Dhaka 1342, Bangladesh Keywords: Checklist; Angiosperms; Rajkandi Reserve Forest; Moulvibazar. Abstract This study was carried out to provide the baseline data on the composition and distribution of the angiosperms and to assess their current status in Rajkandi Reserve Forest of Moulvibazar, Bangladesh. The study reports a total of 549 angiosperm species belonging to 123 families, 98 (79.67%) of which consisting of 418 species under 316 genera belong to Magnoliopsida (dicotyledons), and the remaining 25 (20.33%) comprising 132 species of 96 genera to Liliopsida (monocotyledons). Rubiaceae with 30 species is recognized as the largest family in Magnoliopsida followed by Euphorbiaceae with 24 and Fabaceae with 22 species; whereas, in Lilliopsida Poaceae with 32 species is found to be the largest family followed by Cyperaceae and Araceae with 17 and 15 species, respectively. Ficus is found to be the largest genus with 12 species followed by Ipomoea, Cyperus and Dioscorea with five species each. Rajkandi Reserve Forest is dominated by the herbs (284 species) followed by trees (130 species), shrubs (125 species), and lianas (10 species). Woodlands are found to be the most common habitat of angiosperms. A total of 387 species growing in this area are found to be economically useful. 25 species listed in Red Data Book of Bangladesh under different threatened categories are found under Lower Risk (LR) category in this study area. -

Composition of Canopy Ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) at Ton Nga Chang Wildlife Sanctuary, Songkhla Province, Thailand

ORIGINAL ARTICLE Composition of canopy ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) at Ton Nga Chang Wildlife Sanctuary, Songkhla Province, Thailand Suparoek Watanasit1, Surachai Tongjerm2 and Decha Wiwatwitaya3 Abstract Watanasit, S., Tongjerm, S. and Wiwatwitaya, D. Composition of canopy ants (Hymenoptera: Formicidae) at Ton Nga Chang Wildlife Sanctuary, Songkhla Province, Thailand Songklanakarin J. Sci. Technol., Dec. 2005, 27(Suppl. 3) : 665-673 Canopy ants were examined in terms of a number of species and species composition between in high and low disturbance sites of lowland tropical rainforest at Ton Nga Chang Wildlife Sanctuary, Songkhla province, Thailand, from November 2001 to November 2002. A permanent plot of 100x100 m2 was set up and divided into 100 sub-units (10x10m2) on each study site. Pyrethroid fogging was two monthly applied to collect ants on three trees at random in a permanent plot. A total of 118 morphospecies in 29 genera belonging to six subfamilies were identified. The Formicinae subfamily found the highest species numbers (64 species) followed by Myrmicinae (32 species), Pseudomyrmecinae (10 species), Ponerinae (6 species), Dolichoderinae (5 species) and Aenictinae (1 species). Myrmicinae and Ponerinae showed a significant difference of mean species number between sites (P<0.05) while Formicinae and Myrmicinae also showed a significant difference of mean species number between months (P<0.05). However, there were no interactions between sites and months in any subfamily. Key words : ants, canopy, species composition, distrubance, Songkhla, Thailand 1M.Sc.(Zoology), Assoc. Prof. 2M.Sc. Student in Biology, Department of Biology, Faculty of Science, Prince of Songkla University, Hat Yai, Songkhla 90112 Thailand. 3D.Agr., Department of Forest Biology, Faculty of Forestry, Kasetsart University, Chatuchak, Bangkok 10900 Thailand. -

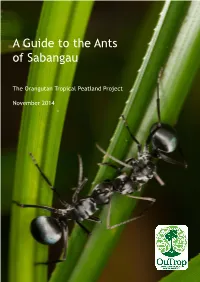

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau

A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project November 2014 A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau All original text, layout and illustrations are by Stijn Schreven (e-mail: [email protected]), supple- mented by quotations (with permission) from taxonomic revisions or monographs by Donat Agosti, Barry Bolton, Wolfgang Dorow, Katsuyuki Eguchi, Shingo Hosoishi, John LaPolla, Bernhard Seifert and Philip Ward. The guide was edited by Mark Harrison and Nicholas Marchant. All microscopic photography is from Antbase.net and AntWeb.org, with additional images from Andrew Walmsley Photography, Erik Frank, Stijn Schreven and Thea Powell. The project was devised by Mark Harrison and Eric Perlett, developed by Eric Perlett, and coordinated in the field by Nicholas Marchant. Sample identification, taxonomic research and fieldwork was by Stijn Schreven, Eric Perlett, Benjamin Jarrett, Fransiskus Agus Harsanto, Ari Purwanto and Abdul Azis. Front cover photo: Workers of Polyrhachis (Myrma) sp., photographer: Erik Frank/ OuTrop. Back cover photo: Sabangau forest, photographer: Stijn Schreven/ OuTrop. © 2014, The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project. All rights reserved. Email [email protected] Website www.outrop.com Citation: Schreven SJJ, Perlett E, Jarrett BJM, Harsanto FA, Purwanto A, Azis A, Marchant NC, Harrison ME (2014). A Guide to the Ants of Sabangau. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project, Palangka Raya, Indonesia. The views expressed in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of OuTrop’s partners or sponsors. The Orangutan Tropical Peatland Project is registered in the UK as a non-profit organisation (Company No. 06761511) and is supported by the Orangutan Tropical Peatland Trust (UK Registered Charity No. -

Digging Deeper Into the Ecology of Subterranean Ants: Diversity and Niche Partitioning Across Two Continents

diversity Article Digging Deeper into the Ecology of Subterranean Ants: Diversity and Niche Partitioning across Two Continents Mickal Houadria * and Florian Menzel Institute of Organismic and Molecular Evolution, Johannes-Gutenberg-University Mainz, Hanns-Dieter-Hüsch-Weg 15, 55128 Mainz, Germany; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: Soil fauna is generally understudied compared to above-ground arthropods, and ants are no exception. Here, we compared a primary and a secondary forest each on two continents using four different sampling methods. Winkler sampling, pitfalls, and four types of above- and below-ground baits (dead, crushed insects; melezitose; living termites; living mealworms/grasshoppers) were applied on four plots (4 × 4 grid points) on each site. Although less diverse than Winkler samples and pitfalls, subterranean baits provided a remarkable ant community. Our baiting system provided a large dataset to systematically quantify strata and dietary specialisation in tropical rainforest ants. Compared to above-ground baits, 10–28% of the species at subterranean baits were overall more common (or unique to) below ground, indicating a fauna that was truly specialised to this stratum. Species turnover was particularly high in the primary forests, both concerning above-ground and subterranean baits and between grid points within a site. This suggests that secondary forests are more impoverished, especially concerning their subterranean fauna. Although subterranean ants rarely displayed specific preferences for a bait type, they were in general more specialised than above-ground ants; this was true for entire communities, but also for the same species if they foraged in both strata. Citation: Houadria, M.; Menzel, F. -

Floribunda Jurnal Sistematika Tumbuhan

PRINTED ISSN : 0215-4706 ONLINE ISSN : 2469-6944 FLORIBUNDA JURNAL SISTEMATIKA TUMBUHAN Floribunda 6(5): 167–206. 30 Oktober 2020 DAFTAR ISI Phenetic Analysis and Distribution of Claoxylon in the Lesser Sunda Islands Adhy Widya Setiawan & Tatik Chikmawati ................................................................... 167–174 Keanekaragaman Morfologi Cempedak [Artocarpus integer (Thunb.) Merr.] di Kabupaten Bangka Tengah dan Selatan Relin Lestari, Anggraeni & Edi Romdhoni .................................................................... 175–182 Melothria (Cucurbitaceae): A New Genus Record of Naturalized Cucumber in Sumatra Wendy A. Mustaqim & Hirmas F. Putra ........................................................................ 183–187 Phyllanthus myrtifolius (Moon ex Wight) Müll.Arg. and Phyllanthus tenellus Roxb. (Phyllanthaceae) in Java Muhammad Rifqi Hariri, Arifin Surya Dwipa Irsyam, Afri Irawan, Zakaria Al-Anshori, Arieh Mountara & Rina Ratnasih Irwanto .................................... 188–194 Keanekaragaman dan Kekerabatan Genetik Artocarpus Berdasarkan Penanda DNA Kloroplas matK & rbcL: Kajian in Silico Dindin H. Mursyidin & M. Irfan Makruf ...................................................................... 195–206 Terakreditasi RISTEKDIKTI No. 36/E/KPT/2019. Peringkat Sinta 2 PRINTED ISSN : 0215-4706 the English Language. Ketentuan-ketentuan yang ONLINE ISSN : 2469-6944 dimuat dalam Pegangan Gaya Penulisan, Penyuntingan, dan Penerbitan Karya Ilmiah Indonesia, serta Scientific Style and Format: CBE Manuals for -

Download This PDF File

VIETNAM JOURNAL OF CHEMISTRY VOL. 53(2e) 127-130 APRIL 2015 DOI: 10.15625/0866-7144.2015-2e-030 IRIDOID CONSTITUENTS FROM THE ANT PLANT HYDNOPHYTUM FORMICARUM Nguyen Phuong Hanh1, Nguyen Huu Toan Phan2*, Nguyen Thi Dieu Thuan2, Le Thi Vien3, Tran Thi Hong Hanh3, Nguyen Van Thanh3, Nguyen Xuan Cuong3, Nguyen Hoai Nam3, Chau Van Minh3 1Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources, Vietnam Academy of Science and Technology (VAST) 2Tay Nguyen Institute of Scientific Research, VAST 3Institute of Marine Biochemistry, VAST Received 23 January 2015; Accepted for Publication 18 March 2015 Abstract Using various chromatographic methods, four iridoids namely asperulosidic acid (1), deacetylasperulosidic acid (2), 6α-hydroxygeniposide (3), and 10-hydroxyloganin (4), were isolated from the methanol extract of the ant plant Hydnophytum formicarum. The structural elucidation was done using 1D and 2D-NMR experiments and comparison of the NMR data with reported values. This is the first report of these compounds from H. formicarum. Keywords. Hydnophytum formicarum, Rubiaceae, ant plant, iridoid. 1. INTRODUCTION standard. The electrospray ionization mass spectra (ESI-MS) were obtained on an Agilent 1260 series The ant plant - Hydnophytum formicarum single quadrupole LC/MS system. Column (Vietnamese names: Ổ kiến, bí kỳ nam) is a herb of chromatography (CC) was performed on silica gel the Rubiaceae. This plant forms a symbiotic (Kieselgel 60, 70–230 mesh and 230–400 mesh, relationship with ants and mainly distributed a long Merck) and YMC RP-18 resins (30–50 μm, Fuji spring sides at altitudes above 600 m. The plant was Silysia Chemical Ltd.). Thin layer chromatography used as folk medicine against liver, alimentary tract, (TLC) used pre-coated silica gel 60 F254 and bone related diseases by some local populations (1.05554.0001, Merck) and RP-18 F254S plates in Tay Nguyen. -

Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plants As Sources of Therapeutic Agents: Their Ethnopharmacological Uses, Chemical Composition, and Biological Activities

biomolecules Review Vascular Epiphytic Medicinal Plants as Sources of Therapeutic Agents: Their Ethnopharmacological Uses, Chemical Composition, and Biological Activities Ari Satia Nugraha 1,* , Bawon Triatmoko 1 , Phurpa Wangchuk 2 and Paul A. Keller 3,* 1 Drug Utilisation and Discovery Research Group, Faculty of Pharmacy, University of Jember, Jember, Jawa Timur 68121, Indonesia; [email protected] 2 Centre for Biodiscovery and Molecular Development of Therapeutics, Australian Institute of Tropical Health and Medicine, James Cook University, Cairns, QLD 4878, Australia; [email protected] 3 School of Chemistry and Molecular Bioscience and Molecular Horizons, University of Wollongong, and Illawarra Health & Medical Research Institute, Wollongong, NSW 2522 Australia * Correspondence: [email protected] (A.S.N.); [email protected] (P.A.K.); Tel.: +62-3-3132-4736 (A.S.N.); +61-2-4221-4692 (P.A.K.) Received: 17 December 2019; Accepted: 21 January 2020; Published: 24 January 2020 Abstract: This is an extensive review on epiphytic plants that have been used traditionally as medicines. It provides information on 185 epiphytes and their traditional medicinal uses, regions where Indigenous people use the plants, parts of the plants used as medicines and their preparation, and their reported phytochemical properties and pharmacological properties aligned with their traditional uses. These epiphytic medicinal plants are able to produce a range of secondary metabolites, including alkaloids, and a total of 842 phytochemicals have been identified to date. As many as 71 epiphytic medicinal plants were studied for their biological activities, showing promising pharmacological activities, including as anti-inflammatory, antimicrobial, and anticancer agents. There are several species that were not investigated for their activities and are worthy of exploration. -

Ants of the Dominican Amber (Hymenoptera: Formicidae). 1. Two New Myrmicine Genera and an Aberrant Pheidole

PSYCHE Vol. 92 1985 No. ANTS OF THE DOMINICAN AMBER (HYMENOPTERA: FORMICIDAE). 1. TWO NEW MYRMICINE GENERA AND AN ABERRANT PHEIDOLE BY EDWARD O. WILSON Museum of Comparative Zoology, Harvard University Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138, U.SoA Ants rival dipterans as the most abundant fossils in the Doini,, can Republic amber. Since they are also phylogenetically compact and relatively easily identified, these insects offer an excellent opportunity to study dispersal and evolution in a Tertiary West Indian fauna. The age of the Dominican amber has not yet been determined, but combined stratigraphic and foraminiferan analyses of its matrix suggest an origin at least as far back as the early Miocene (Saunders in Baroni Urbani and Saunders, 1982). am inclined to favor ttis minimal age (about 20 million years) or at most a late Oligocene origin, for the following reason. In a sample of 596 amber pieces containing an estimated 1,248 ants that recently examined (439 now deposited in the Museum of Comparative Zoology), found 36 genera and well-defined subgenera, to which may be added one other, Trachymyrmex, reported earlier by Baroni Urbani (1980a). Of these 37 taxa only three, or 8%, are unknown from the living world fauna (see Table 1). The relative contemporaneity of the Dominican amber ants contrasts with that of the Baltic amber, which is Eocene to early Oligocene in age (Larsson, 1978) and pos- sesses 44% extinct genera; that is, 19 of the 43 genera recorded by Wheeler (1914) are unknown among living ants. The Dominican amber ants also differ to a similar degree from those of the Floris- sant, Colorado, shales, which are upper Oligocene in age and con-. -

Phytogeographic Review of Vietnam and Adjacent Areas of Eastern Indochina L

KOMAROVIA (2003) 3: 1–83 Saint Petersburg Phytogeographic review of Vietnam and adjacent areas of Eastern Indochina L. V. Averyanov, Phan Ke Loc, Nguyen Tien Hiep, D. K. Harder Leonid V. Averyanov, Herbarium, Komarov Botanical Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Prof. Popov str. 2, Saint Petersburg 197376, Russia E-mail: [email protected], [email protected] Phan Ke Loc, Department of Botany, Viet Nam National University, Hanoi, Viet Nam. E-mail: [email protected] Nguyen Tien Hiep, Institute of Ecology and Biological Resources of the National Centre for Natural Sciences and Technology of Viet Nam, Nghia Do, Cau Giay, Hanoi, Viet Nam. E-mail: [email protected] Dan K. Harder, Arboretum, University of California Santa Cruz, 1156 High Street, Santa Cruz, California 95064, U.S.A. E-mail: [email protected] The main phytogeographic regions within the eastern part of the Indochinese Peninsula are delimited on the basis of analysis of recent literature on geology, geomorphology and climatology of the region, as well as numerous recent literature information on phytogeography, flora and vegetation. The following six phytogeographic regions (at the rank of floristic province) are distinguished and outlined within eastern Indochina: Sikang-Yunnan Province, South Chinese Province, North Indochinese Province, Central Annamese Province, South Annamese Province and South Indochinese Province. Short descriptions of these floristic units are given along with analysis of their floristic relationships. Special floristic analysis and consideration are given to the Orchidaceae as the largest well-studied representative of the Indochinese flora. 1. Background The Socialist Republic of Vietnam, comprising the largest area in the eastern part of the Indochinese Peninsula, is situated along the southeastern margin of the Peninsula. -

Report on Pitfall Trapping of Ants at the Biospecies Sites in the Nature Reserve of Orange County, California

Report on Pitfall Trapping of Ants at the Biospecies Sites in the Nature Reserve of Orange County, California Prepared for: Nature Reserve of Orange County and The Irvine Co. Open Space Reserve, Trish Smith By: Krista H. Pease Robert N. Fisher US Geological Survey San Diego Field Station 5745 Kearny Villa Rd., Suite M San Diego, CA 92123 2001 2 INTRODUCTION: In conjunction with ongoing biospecies richness monitoring at the Nature Reserve of Orange County (NROC), ant sampling began in October 1999. We quantitatively sampled for all ant species in the central and coastal portions of NROC at long-term study sites. Ant pitfall traps (Majer 1978) were used at current reptile and amphibian pitfall trap sites, and samples were collected and analyzed from winter 1999, summer 2000, and winter 2000. Summer 2001 samples were recently retrieved, and are presently being identified. Ants serve many roles on different ecosystem levels, and can serve as sensitive indicators of change for a variety of factors. Data gathered from these samples provide the beginning of three years of baseline data, on which long-term land management plans can be based. MONITORING OBJECTIVES: The California Floristic Province, which includes southern California, is considered one of the 25 global biodiversity hotspots (Myers et al. 2000). The habitat of this region is rapidly changing due to pressure from urban and agricultural development. The Scientific Review Panel of the State of California's Natural Community Conservation Planning Program (NCCP) has identified preserve design parameters as one of the six basic research needs for making informed long term conservation planning decisions. -

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION on the TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and Plants

BIODIVERSITY CONSERVATION ON THE TIWI ISLANDS, NORTHERN TERRITORY: Part 1. Environments and plants Report prepared by John Woinarski, Kym Brennan, Ian Cowie, Raelee Kerrigan and Craig Hempel. Darwin, August 2003 Cover photo: Tall forests dominated by Darwin stringybark Eucalyptus tetrodonta, Darwin woollybutt E. miniata and Melville Island Bloodwood Corymbia nesophila are the principal landscape element across the Tiwi islands (photo: Craig Hempel). i SUMMARY The Tiwi Islands comprise two of Australia’s largest offshore islands - Bathurst (with an area of 1693 km 2) and Melville (5788 km 2) Islands. These are Aboriginal lands lying about 20 km to the north of Darwin, Northern Territory. The islands are of generally low relief with relatively simple geological patterning. They have the highest rainfall in the Northern Territory (to about 2000 mm annual average rainfall in the far north-west of Melville and north of Bathurst). The human population of about 2000 people lives mainly in the three towns of Nguiu, Milakapati and Pirlangimpi. Tall forests dominated by Eucalyptus miniata, E. tetrodonta, and Corymbia nesophila cover about 75% of the island area. These include the best developed eucalypt forests in the Northern Territory. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 1300 rainforest patches, with floristic composition in many of these patches distinct from that of the Northern Territory mainland. Although the total extent of rainforest on the Tiwi Islands is small (around 160 km 2 ), at an NT level this makes up an unusually high proportion of the landscape and comprises between 6 and 15% of the total NT rainforest extent. The Tiwi Islands also include nearly 200 km 2 of “treeless plains”, a vegetation type largely restricted to these islands. -

Poneromorfas Do Brasil Miolo.Indd

10 - Citogenética e evolução do cariótipo em formigas poneromorfas Cléa S. F. Mariano Igor S. Santos Janisete Gomes da Silva Marco Antonio Costa Silvia das Graças Pompolo SciELO Books / SciELO Livros / SciELO Libros MARIANO, CSF., et al. Citogenética e evolução do cariótipo em formigas poneromorfas. In: DELABIE, JHC., et al., orgs. As formigas poneromorfas do Brasil [online]. Ilhéus, BA: Editus, 2015, pp. 103-125. ISBN 978-85-7455-441-9. Available from SciELO Books <http://books.scielo.org>. All the contents of this work, except where otherwise noted, is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International license. Todo o conteúdo deste trabalho, exceto quando houver ressalva, é publicado sob a licença Creative Commons Atribição 4.0. Todo el contenido de esta obra, excepto donde se indique lo contrario, está bajo licencia de la licencia Creative Commons Reconocimento 4.0. 10 Citogenética e evolução do cariótipo em formigas poneromorfas Cléa S.F. Mariano, Igor S. Santos, Janisete Gomes da Silva, Marco Antonio Costa, Silvia das Graças Pompolo Resumo A expansão dos estudos citogenéticos a cromossomos de todas as subfamílias e aquela partir do século XIX permitiu que informações que apresenta mais informações a respeito de ca- acerca do número e composição dos cromosso- riótipos é também a mais diversa em número de mos fossem aplicadas em estudos evolutivos, ta- espécies: Ponerinae Lepeletier de Saint Fargeau, xonômicos e na medicina humana. Em insetos, 1835. Apenas nessa subfamília observamos carió- são conhecidos os cariótipos em diversas ordens tipos com número cromossômico variando entre onde diversos padrões cariotípicos podem ser ob- 2n=8 a 120, gêneros com cariótipos estáveis, pa- servados.