Infanticide Attacks and Associated Epimeletic Behaviour in Free

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

15.03.26 Adjudicación Obras Marín, Pontevedra

MINISTERIO GABINETE DE AGRICULTURA, ALIMENTACIÓN DE PRENSA Y MEDIO AMBIENTE A través de la sociedad estatal Aguas de las Cuencas de España (Acuaes) El Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente adjudica por 3,3 millones de euros las obras de mejora del abastecimiento a Marín (Pontevedra) • Se construirán dos nuevos tramos de distribución de agua, el primero de aducción al nuevo depósito a ejecutar en Pardavila de 2.000 m 3 de capacidad, y un segundo tramo de conexión con la red de Marín • La actuación forma parte del proyecto de “Mejora del abastecimiento de agua a Pontevedra y su Ría”, cuya inversión total asciende a 39,9 millones de euros 26 de marzo de 2015- El Consejo de Administración de la sociedad estatal Aguas de las Cuencas de España (Acuaes) del Ministerio de Agricultura, Alimentación y Medio Ambiente ha adjudicado, por 3.332.386 euros, las obras del Eje de Marín, que forman parte de la actuación de “Mejora del abastecimiento de agua a Pontevedra y su Ría”, cuya inversión total asciende a 39,9 millones de euros. La empresa adjudicataria ha sido Ortiz, Construcciones y Proyectos, S. A. U., que Nota de prensa Nota tendrá un plazo de 8 meses para ejecutar los trabajos. Las obras del Eje de Marín consisten en la construcción de dos nuevos tramos de distribución de agua: el primero, de aducción al nuevo depósito a ejecutar en Pardavila, de 2.000 m 3 de capacidad; y el segundo, de conexión con la red de Marín ya existente. El tramo de aducción, de 4.216 metros de longitud y un diámetro de 400 mm, tendrá su origen en la última fase de la obra correspondiente al proyecto del nuevo abastecimiento de agua a Pontevedra y su ría correspondiente a la margen izquierda, que actualmente se encuentra en ejecución. -

20210819 Oficinas Emisión Tarxetas.Xlsx

OFIC. ABANCA PONTEVEDRA OFICINAS NAS QUE OPTER AS TARXETAS DE TRANSPORTE PUBLICO E XENTE NOVA Clave Provincia Concello Localidade Dirección CP Teléfono TPG TXN Oficina 576 PONTEVEDRA A Cañiza A Cañiza CL. PROGRESO, 77 36880 986663002 SI SI 5031 PONTEVEDRA A ESTRADA A ESTRADA CL. CALVO SOTELO, 9 36680 986590003 SI SI 5038 PONTEVEDRA A Guarda A Guarda CL. CONCEPCION ARENAL, 44 36780 986609002 SI SI 5011 PONTEVEDRA Arbo Arbo CL. VAZQUEZ ESTEVEZ, 7 36430 986664800 SI SI 5015 PONTEVEDRA BAIONA BAIONA CL. CARABELA LA PINTA, 10 36300 986385001 SI SI 5072 PONTEVEDRA BAIONA SABARIS CL. JULIAN VALVERDE, 1 36393 986386004 SI SI 5411 PONTEVEDRA BARRO SANTO ANTONIÑO CL. BALADAS, 1-SAN ANTONIÑO-PERDECANAI 36194 986711013 SI SI 5017 PONTEVEDRA BUEU BUEU CL. EDUARDO VINCENTI, 29 36930 986390009 SI SI 5019 PONTEVEDRA Caldas de Reis Caldas de Reis CL. JOSE SALGADO, 2 36650 986539009 SI SI 5021 PONTEVEDRA CAMBADOS CAMBADOS AV. GALICIA, 15 36630 986526004 SI SI 5125 PONTEVEDRA CAMBADOS CORVILLON CL. RIVEIRO, 13- B 36634 986526003 SI SI 510 PONTEVEDRA CAMPO LAMEIRO CAMPO LAMEIRO CL. BERNARDO SAGASTA, 37 36110 986752032 SI SI 5010 PONTEVEDRA CANGAS ALDAN CL. SAN CIBRAN, 15 36945 986391000 SI SI 5022 PONTEVEDRA CANGAS CANGAS AV. EUGENIO SEQUEIROS, 13 36940 986392018 SI SI 5079 PONTEVEDRA CANGAS COIRO AV. OURENSE, 27 36947 986392017 SI SI 5118 PONTEVEDRA CANGAS HIO LG. IGLESARIO, 57 36945 986391001 SI SI 5026 PONTEVEDRA CERDEDO-COTOBADE CERDEDO CR. OURENSE, 41 36130 986754800 SI SI 5033 PONTEVEDRA FORNELOS DE MONTES FORNELOS DE MONTES PZ. LA IGLESIA, 17 36847 986766700 SI SI 1194 PONTEVEDRA Gondomar Gondomar CL. -

Conservas Pescamar

Case Study Conservas Pescamar Operational Complexities Solved with Integration Solution delivered by Parsec Certified Partner 01 Conservas Pescamar Operational Complexities Solved with Integration Food & Beverage Industry With global demand ever increasing, Conservas Pescamar needed something that could work with their current infrastructure and could increase their capacity of their existing site. Utilized TrakSYSTM Features & Functions Planning & Scheduling Job/WIP Management Traceability & Genealogy OEE Material Management Manufacturing Intelligence Quality and SPC Enterprise Visibility 02 Conservas Pescamar Operational Complexities Solved with Integration Conservas Pescamar’s growing international demand needed consistent and timely information to overcome capacity roadblocks. 03 Conservas Pescamar Operational Complexities Solved with Integration Company Overview In 1961 Mr. Alfonso García López opened utilization of their existing infrastructure. By a seafood canning factory, that site has unlocking the hidden potential of both their now become a large industrial complex in equipment and factory space, Conservas Poio, in the province of Pontevedra, Spain. Pescamar was able to greatly increase Conservas Pescamar enjoys an excellent efficiencies and output using their existing geographical position on the coast of Galicia, infrastructure. in northwest Spain1. Connecting the TrakSYS™ solution to The location offers access to a large variety planning and scheduling, Conservas of marine species, which are carefully Pescamar was able to cut hours all while processed into premium products with the maintaining quality and quantity produced. best quality and flavor for the consumer. With this increase in throughput per dollar Staying committed to a tradition of quality spent, Conservas Pescamar was able to cut and innovation, Conservas Pescamar has COGS (cost of goods sold) dramatically. -

Entidades Socias

RELACIÓN DE ASOCIADOS GALP RÍA DE PONTEVEDRA MESA SECTORIAL CONCELLO tipo ENTIDADE enderezo cp Rúa Real, s/n (Oficina de 1 ECONOMICA E LABORAL AGARIMO 36860 Ponteareas Turismo de Ponteareas) 2 ECONOMICA E LABORAL SANXENXO COMERCIANTES ENTRETENDAS CCU Progreso, nº 79 local 3B, 36960 Sanxenxo R/ Fernandez Villaverde, 4 1º 3 ECONOMICA E LABORAL PONTEVEDRA FEDERACIÓN DE EMPRESAS COOP. SINERXIA 36002 Pontevedra Andar dereito Praza de Abastos Avda. Madrid 4 ECONOMICA E LABORAL SANXENXO COMERCIANTES ASOCIACIÓN PRAZA DE ABASTOS DE SANXENXO APASA 36960 SANXENXO s.n. 5 ECONOMICA E LABORAL MARÍN COMERCIANTES Asociación de Comerciantes Estrela de Marín Rúa Real 10, baixo 36900 Marín Praza de Abastos - Estrada A 6 ECONOMICA E LABORAL SANXENXO COMERCIANTES ASOCIACIÓN PRAZA DE ABASTOS DE PORTONOVO: APAPO 36970 SANXENXO Lanzada - Portonovo. Portonovo 7 ECONOMICA E LABORAL PONTEVEDRA EMPRESARIOS AEMPE 8 ECONOMICA E LABORAL PONTEVEDRA EMPRESARIOS AJE PONTEVEDRA C/ Herreros 28,4ªplanta - Oficina 44 36002 PONTEVEDRA 9 ECONOMICA E LABORAL POIO EMPRESARIOS ASOCIACIÓN DE POIO DE AUTOTURISMOS - TAXIS Avda. Porteliña, 25 36993 POIO 10 ECONOMICA E LABORAL PONTEVEDRA EMPRESARIOS APE GALICIA 11 ECONOMICA E LABORAL SANXENXO deportiva ESTACIÓN NÁUTICA RÍAS BAIXAS Luis de Rocafort 53-201 A 36960 Sanxenxo 12 ECONOMICA E LABORAL PONTEVEDRA EMPRESARIOS Asociación Galega de actividades náuticas - AGANPLUS 13 ECONOMICA E LABORAL Bueu Comerciantes Asoc. De Profesionais da Praza de Abastos de Bueu Rúa Montero Ríos 99 - Pza de Abastos 36930 BUEU 14 ECONOMICA E LABORAL Bueu -

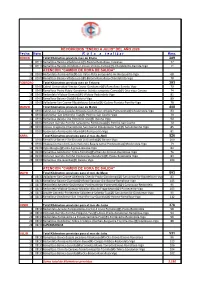

RECORRIDOS "ENERO a JULIO" DEL AÑO 2020 Fecha Hora R U T a a R E a L I Z a R Kms

RECORRIDOS "ENERO A JULIO" DEL AÑO 2020 Fecha Hora R u t a a r e a l i z a r Kms. ENERO Total Kilómetros previsto mes de Enero 289 5 09:15 Ramallosa-Baiona-Viladesuso (@)-Baiona-Ramallosa-Traviesas 72 12 09:15 Ramallosa-Baredo-Gondomar-Couso-Vincios-Camos(@)-Chandebrito-Garrida-Vigo 71 ATENCION "CAMBIO DE HORA DE SALIDA" 19 09:00 Redondela-Pontevedra(@)-Los Valos-Pista aeropuerto-Av.Aeropuerto-Vigo 68 26 09:00 Ramallosa-Baiona-Viladesuso (@)-Baiona-Ramallosa-Chandebrito-Vigo 78 FEBRERO Total Kilómetros previsto mes de Febrero 383 2 09:00 Cabral-Universidad-Vincios-Couso-Gondomar(@)-Ramallosa-Baredo-Vigo 70 9 09:00 Ramallosa-Pedra Rubia-Gondomar-Subida autopista-Camos(@)-Crta vieja-Coruxo 74 16 09:00 Redondela-Vilaboa-Domaio(@)-Vilaboa-Redondela-Vigo 81 23 09:00 Ramallosa-Baiona-Oia(@)-Baiona-Vigo 80 25 09:00 Valladares-San Cosme-Ribadelouro-Salceda(@)-Gulans-Pianista-Porriño-Vigo 78 MARZO Total Kilómetros previsto mes de Marzo 488 1 09:00 Cabral-Los Valos-Cepeda-Amoedo-Soutomaior-Arcade-Pontevedra(@)-Redondela-Vigo 83 8 09:00 Gondomar-San Antoniño-Tuy(@)-Porriño-San Cosme-Vigo 79 15 09:00 Ramallosa-Baiona-Oia-Portecelo-Oia(@)-Baiona-Vigo 90 22 09:00 Portanet-Garrida-Porriño-Salvatierra-Ponteareas(@)-Porriño-San Cosme 70 28 09:00 Coruxo-Fragoselo-Chandebrito-San Cosme-Ribadelouro-Tuy(@)-San Antoniño-Vigo 85 29 09:00 Redondela-Pontevedra-Marín(@)-Pontevedra-Vigo 81 ABRIL Total Kilómetros previstos para el mes de Abril 526 5 09:00 Ramallosa-Baiona-Oia-Entrada La Guardia(@)-Baiona-Vigo 100 9 09:00 Vilaboa-Domaio km6-Cotorredondo-Bajada ramal -

14 De Xaneiro

ORDEN de 14 de enero de 2021 por la que modifica la Orden de 3 de diciembre de 2020 por la que se establecen medidas de prevención específicas como consecuencia de la evolución de la situación epidemiológica derivada del COVID-19 en la CCAA Galicia Todos los perímetros individuales Nivel medio-alto (Anexo III) 253 concellos Nivel de máximas restricciones (Anexo IV) 60 concellos A Coruña, Arteixo, Cambre, Culleredo, Oleiros, Carballo, Santiago de Compostela, Ames, Ribeira, Boiro, Rianxo, Noia, Ferrol, Narón e Fene Cee, Camariñas, Cerceda, Laxe, Vimianzo, Cabanas, Pontedeume, Ortigueira, Outes, Porto do Son, A Pobra do Caramiñal, Melide, Oroso, Trazo e Val do Dubra Vilalba e Viveiro Xove Ourense, Barbadás, Verín e O Carballiño Allariz, Monterrei e Xinzo de Limia A Estrada, Poio, Bueu, Moaña, Baiona, Ponteareas, Redondela, A Guarda, Tomiño, Tui, Vilagarcía e Vilanova A Illa de Arousa, Valga, Pontecesures, Caldas de Reis, Cuntis, Oia, O Rosal e Salvaterra de Miño REUNIONES 4 personas TOQUE DE QUEDA Desde las 22:00 horas hasta las 06:00 horas LUGARES DE CULTO ⅓ capacidad Distancia 1,5 m No permido exterior Anexos en Orden 03_12_2020 Velatorios: Máx. 25 personas exterior - Máx. 10 personas interior 3.1 VELATORIOS Y ENTIERROS Enerros: 25 personas + ministro de culto 3.2 CELEBRACIONES CEREMONIAS 100 personas exterior RELIGIOSAS O CIVILES (BBC) 50 personas interior 3.3 COMERCIOS MINORISTAS 50% ACT. SERV. PROFESIONALES Atención preferente a > de 75 años 3.4 CENTROS O PARQUES 30% capacidade centro en zonas comunes COMERCIALES Y GRANDES 30% en establecimientos SUPERFICIES Atención preferente a > de 75 años 3.6 ACADEMIAS, AUTOESCUELAS 50% capacidad CENTROS PRIVADOS Grupos de 4 personas Grupos de 4 personas NO barra NO barra 30% interior sentados 50% terrazas INTERIOR cerrado 50% terrazas 3.7 HOSTELERÍA Hasta las 18:00 h. -

Experience the Region of Pontevedra 08 an Artistic Treasure

EXPERIENCE THE REGION OF PONTEVEDRA 08 AN ARTISTIC TREASURE Stroll around the town of Pontevedra and be immersed in its art and history. The streets and squares are adorned with century-old granite, with medieval manor houses and churches that embellish the town. Visit its interesting museums and explore its surroundings, discover pazos and monasteries and follow the traces of petroglyphs in natural landscapes of great beauty. Discover the region of Pontevedra, an artistic treasure that comprises the towns of Pontevedra, Campo Lameiro, Barro, Poio, Vilaboa, Ponte Caldelas and A Lama. Pontevedra is full of art in every corner. The squares and streets of the old town remind us of a medieval past, in which the Pilgrim's Way to Santiago de Compostela was a very important meeting point. The Provincial Museum of Pontevedra houses archaeological, artistic and ethnographic collections of great value and invites us on a journey through the history of the province from Prehistory until the present time. 1 - A Lama 2 - Ponte Caldelas The city of Pontevedra boasts even more treasures, such as the 3 - Vilaboa remains of the ancient archiepiscopal towers, the monastery of San 4 - Pontevedra Salvador de Lérez or the sumptuous manor house Pazo de Lourizán. 5 - Poio The region also gathers an important archaeological heritage, such as 6 - Barro the groups of rock carvings - petroglyphs - from the Bronze Age that can 7 - Campo Lameiro be admired in Campo Lameiro, Tourón or A Caeira. The coastal inlet Ría de Pontevedra, with towns such as Poio or the parishes of Combarro or Samieira, is home to an interesting culinary offer and boasts a large number of interesting natural and cultural spots. -

Quality of Life in Cities of Galicia: an Empirical Application

Boletín de la Asociación de GeógrafosQuality Españolesof life in cities N.º of59 Galicia: - 2012, an págs. empirical 453-458 application I.S.S.N.: 0212-9426 QUALITY OF LIFE IN CITIES OF GALICIA: AN EMPIRICAL APPLICATION Andrés Precedo Ledo Alberto Míguez Iglesias Departamento de Geografía. Universidad de Santiago de Compostela [email protected], [email protected] Javier Orosa González Departamento de Análisis Económico y Administración de Empresas Universidad de A Coruña [email protected] I. INTRODUCTION The object of investigation of this work consists of comparing the quality of life of the seven most important cities of Galicia and its urban areas. We do two comparative analyses: the first one uses as spatial unit the municipality and the second one includes the metropolitan areas, by means of a ranking city with major quality of life. The methodology used is the Urban Quality of Life Index (Leva, 2007) and the sources the information has been extracted are: National Institute of Statistics (INE, 2004), Department of Economy and Estate (2004), Socioeconomic Atlas of Galicia (2005), Ministerio del Interior (2004), ESPON (2009) and Urban Audit. II. THEORETICAL FRAME The study of the concept quality of life has experienced, as all the theoretical components, an evolution throughout the time. The main precedents in the study of the quality of life we might place between the 20s and 40s, in United States with the research of social indicators. (Ogburn, 1933). The analysis of the studies realized on quality of life shackler meets an element: the definitions of the quality of life differ some of others (Rupprecht, 1993). -

Dos Monasterios Pontevedreses: Poio Y Armenteira

DOS MONASTERIOS PONTEVEDRESES: POIOY ARMENTEIRA Josefina Cerviño Lago Profesora de Historia da Arte Universidade da Coruña EL MONASTERIO DE SAN JUAN DE POlO Se cree que lo fundó San Fructuoso, nacido en Toledo en el seno de una familia noble y que muy pronto se convirtió en consejero del rey Re cesvinto. En sus numerosas fundaciones repartidas por Galicia, Portugal y la Bética, es fundamental el concepto jerárquico de la autoridad del abad. Aunque sus monjes poseían derechos democráticos e individuales para enfrentarse a él e incluso deponerlo. Este santo muere el 16 de abril del año 665, siendo enterrado, como era su deseo, en el monasterio de Montelios. Poio, desde su fundación en el siglo VII, recibió gran cantidad de donaciones de cotos y villas por parte de los reyes Alfonso VI y Fernando 1, siendo muy importantes las realizadas por el conde Don Ramón y su esposa Doña Urraca en el año 1105 Y por esta reina al abad Fromarico en 1116. Los monjes de Poio llegaron a tener derechos y posesiones en las Tierras del Salnés, ya que continuaron gozando de la protección de los monarcas Fernando JI, Fernando IV, Alfonso XL.Al igual que otros ceno bios, también sufrió invasiones, como lo constata el hecho de su recons trucción en el siglo XI, financiada por el rey Bermudo III. Del primitivo 192 JOSEFINA CERVIÑO LAGO monasterio visigodo que ocupó un lugar distinto del actual sólo se conser va el sepulcro de Santa Trahamunda, patrona de la «saudade». Poio pasa a formar parte de la congregación de San Benito de Valladolid en 1547, sien do nombrado abad Fray Gregario de Alvarado. -

Previsiın Vacantes ADP XT Pontevedra.Numbers

PETICIÓN PROFESORADO CURSO 2015-2016 INFANTIL-PRIMARIA CENTRO EI EP FI FF EM EF PT AL DO CEIP Pedro Antonio Cerviño-Campo Lameiro 1 1 CPI Aurelio Marcelino Rey García-Cuntis 3 CPI Santa Lucía-Moraña 1 1 CPI Domingo Fontán-Portas 1 1 1 CEP Plurilingüe de Riomaior-Vilaboa 2 1 1 CPI do Toural-Vilaboa 5 1 1 1 CRA de Vilaboa Consuelo González Martínez 1 CEIP Amor Ruibal-Barro 4 1 CPI Alfonso VII-Caldas de Reis 1 1 1 1 CEIP San Clemente de César-Caldas de Reis 1 1 1 CEP Marcos da Portela-Pontevedra 3 1 1 CEIP Froebel-Pontevedra 3 1 1 CEIP Pérez Viondi-A Estrada 1 1 1 CEIP de Figueroa-A Estrada 1 1 1 CEIP do Foxo-A Estrada 1 1 1 CEIP Plurilingüe de Oca-A Estrada 1 1 CEIP Cabada Vázquez-A Estrada 1 IES Antón Losada Diéguez-A Estrada 1 EPA Nelson Mandela 1 CEIP San Xoan Bautista de Cerdedo 1 CEIP A Lama 1 1 1 1 EEI de Romariz-Soutomaior 1 CPI Manuel Padín Truiteiro-Soutomaior 1 3 1 1 CEIP Curros Enríquez-Pazos de Borbén 1 3 EEI de Outeiro-Pazos de Borbén 1 CEIP Ponte Sampaio 1 CEIP San Martiño-Pontevedra 1 1 1 1 CEIP Cabanas-Pontevedra 1 6 1 1 CEIP de Tenorio-Cotobade 1 1 CEIP de Carballedo-Cotobade 1 CEIP Nosa Señora dos Dores-Forcarei 1 1 CEIP Soutelo-Forcarei 1 1 CEIP Doutor Suárez-Fornelos de Montes 1 1 1 1 1 1 CEIP A Reigosa-Pontecaldelas 4 1 CEIP Manuel Cordo Boullosa 1 CPI de Rodeiro 1 CEIP Manuel Vidal Portela-Pontevedra 2 1 2 IES A Paralaia-Moaña 1 CEIP de Rebordáns-Tui 1 1 1 CEIP de Guillarei-Tui 1 1 1 CEIP de Caldelas-Tui 1 CEIP de Pazos de Reis-Tui 1 CEIP de Randufe-Tui 1 1 1 1 CEIP Nº1-Tui 1 1 1 1 CEIP Plurilingüe Nº2-Tui 3 3 1 1 -

Pontevedra Pontevedra

PONTEVEDRA PONTEVEDRA HORARIO DE FRANQUICIA: De 8 a 14 h y de 15:45 a 20 h. Sábados de 10 a 13 h. 902 300 400 RECOGIDA Y ENTREGAS EN LOCALIDADES SIN CARGO ADICIONAL DE KILOMETRAJE SERVICIOS DISPONIBLES Acuña (Vilaboa) Igrexa, A (Sta. María Xe.) Puente-Caldelas SERVICIO URGENTE HOY/URGENTE BAG HOY. Aguete (Seixo) Justanes Reigosa, La RECOGIDAS Y ENTREGAS, CONSULTAR CON SU FRANQUICIA. SERVICIO URGENTE 8:30. RECOGIDAS: Mismo horario del Servicio Alba (Pontevedra) Lérez Salcedo (Pontevedra) Urgente 10. ENTREGAS EN DESTINO: El día laborable siguiente antes Almofrei (San Lourenzo) Liñares (Poio) Samieira de las 8:30 h** (Consultar destinos). SERVICIO URGENTE 10. RECOGIDAS: Límite en esta Franquicia 20 h Ardán Lourizán S. Juan de Poio destino Álava, Asturias, Ávila (excepto Arévalo), Badajoz, Burgos, Cá- Ardis (Poio) Marcón S. Salvador de Poio ceres (excepto Navalmoral, Plasencia y Coria), Cantabria, A Coruña, Guadalajara (excepto Molina A. y Sigüenza), Guipuzcoa, León, Lugo, Bao, El (Pontevedra) Marín S. Vicente Cerponzone Madrid, Navarra (excepto Tudela), Ourense, Palencia, Pontevedra, Barro (Pontevedra) Marín (Escuela Naval) Santa Ana (Pontevedra) Rioja, Salamanca, Segovia, Toledo (excepto Quintanar y Tembleque), Valladolid, Vizcaya y Zamora. Berducido (Xeve) Mogor Sta. Cristina de Cobres 19 h destino Andorra, España, Gibraltar y Portugal. ENTREGAS EN Bertola Mollabao Santa Margarita (Pon.) DESTINO: El día laborable siguiente a primera hora de la mañana en Andorra, España, Gibraltar y Portugal. En esta Franquicia de 8 Bora Montecelo Santa María de Xeve a 10:30 h*. SERVICIO URGENTE 12/URGENTE 14/DOCUMENTOS 14/ Campaño Montecelo (Seixo) Sartal, O (Poio) URGENTE BAG14. RECOGIDAS: Mismo horario del Servicio Urgente Campelo (Poio) Monteporreiro Seara, A (Poio) 10. -

36015202-CEIP De Lourido Poio 597037

36015202-CEIP de Lourido Poio 597037 - Educaciónespecial: Non 597032 S 36013710 - EEI do Vao Audicióne Linguaxe bilingüe 36007060-CEIP Plurilingüe de Poio 597033 - Idioma estranxeiro: Non 597038 N Chancelas Francés bilingüe 36008751-CEIP Plurilingüe Salvaterra de 597036 - Educaciónespecial: Non 597037 N Infante Felipe de Borbón Miño Pedagoxía Terapéutica bilingüe 36009524-CEP Plurilingüe Pedro Tomiño 597038 - Primaria Inglés 597032 N Caselles Beltrán 36015202-CEIP de Lourido Poio 597033 - Idioma estranxeiro: Non 597038 N Francés bilingüe 36008751-CEIP Plurilingüe Salvaterra de 597038 - Primaria Non 597032 N Infante Felipe de Borbón Miño bilingüe 36004460-CEIP de Ardán MarÃn 597037 - Educaciónespecial: Non 597038 N Audición e Linguaxe bilingüe 36007242-CEIP de Viñas Poio 597039 - Orientación Non 597036 S 36013710 - EEI do Vao bilingüe 36006109-CEIP de Parada- Pontevedra 597032 - Idioma estranxeiro: Non 597038 N Campañó Inglés bilingüe 36006122-CEIP A Xunqueira Nº 1 Pontevedra 597032 - Idioma estranxeiro: Non 597038 N Inglés bilingüe 36016051-CEIP Seis do Nadal Vigo 597031 - Educacióninfantil Non 597032 N bilingüe 36010460-CEIP Alfonso D. Vigo 597031 - Educacióninfantil Non 597037 N RodrÃguez Castelao bilingüe 36010460-CEIP Alfonso D. Vigo 597035 - Música Non 597038 N RodrÃguez Castelao bilingüe 36015263-CEIP Plurilingüe de VilagarcÃa de 597037 - Educaciónespecial: Non 597036 S 36012742 - CEIP de Vilaxoán Rubiáns Arousa Audicióne Linguaxe bilingüe 36013023-CEIP de San Roque Vilanova de 597037 - Educaciónespecial: Non 597036