Postwar Vice Crime and Political Corruption in Portland

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Portland Daily Press: April 24,1873

PORTLAND ] ESTABLISHED JUXE 3:i. 1S03. VOL. 13. PORTLAND THORS DAT THF PORTLAND DAILY PRESS business cards. i REAL ESTATE. WANTS, LOST, FOUND. TO LEI. j The Rani's Secret or Poetic Published every day (Sundays excepted) by. the | MISCELLANEOUS. PRESS. Reticence THE [From the Atlanta Weekly.] PORTLAND PUKI.ISniXR CO., House to Rent or the sub-editor W. c. ( LARK, Hotel Property for Sale ! Warned Lease. APR. 24, 1S7:{ j Yesterday morning came iu- upper tenement of bonne No. THURSDAYMORNING, t > At 109 Exciiaxge St. Portland. MAN who Furniture. rpiIE 31 Emerv St our sanctum and reminded us that we understands repairing X of six rooms, all KOHLING j 103 FEDERAL STREET, Federal St. consisting very pleasantlv“y eUusi'i n- IjST northboro mass. A Apply at 125 ated; with Gas and Sebago Water, hadn’t given out for the fourth Terms: Eight Dollars a Year in advance 5 Woors East of Temple Si., apr23 ti and J any poetry Assabet House, beautifully situated on public Inquire on tho prcmisca. Gossip Gleanings. rpilE-*• i So we took out the roll of square in center of on 2c aprlDdtf WILLIAM II. HAS GOT HLS page. manuscript THE MAINE STATE the village, Railroad GREEN. PRESS GAS AM) WATER miles from tBostou. House is new and of moderr ! lift wit 1 us by the Poet's wife, and selected stylo, and contains 38 rooms, dance b lliards&e. Tommy wants to know if the backwoods is Titcrsday nail, WANTED. To Let, the published every Morning at S’ 50 a Large stable, 30 stalls. -

The Pulitzer Prizes 2020 Winne

WINNERS AND FINALISTS 1917 TO PRESENT TABLE OF CONTENTS Excerpts from the Plan of Award ..............................................................2 PULITZER PRIZES IN JOURNALISM Public Service ...........................................................................................6 Reporting ...............................................................................................24 Local Reporting .....................................................................................27 Local Reporting, Edition Time ..............................................................32 Local General or Spot News Reporting ..................................................33 General News Reporting ........................................................................36 Spot News Reporting ............................................................................38 Breaking News Reporting .....................................................................39 Local Reporting, No Edition Time .......................................................45 Local Investigative or Specialized Reporting .........................................47 Investigative Reporting ..........................................................................50 Explanatory Journalism .........................................................................61 Explanatory Reporting ...........................................................................64 Specialized Reporting .............................................................................70 -

ISRC MBRS/CAMPAIGN/CORONATION MEETING MINUTES September 23, 2019

ISRC MBRS/CAMPAIGN/CORONATION MEETING MINUTES September 23, 2019 Meeting was called to order at 7:02pm Board Members in Attendance – Attendance was not taken due to this being a non-required meeting. Members in Attendance – Attendance was not taken due to this being a non-required meeting. REPORTS: Treasurer’s Report – Don Hood – Nothing to report General Membership – Hellin/Jim – 69 – 2 online and memberships paid last night at Announcement Secretary’s Report – Nikki/Mark – Nothing to report Vice President’s Report – Summer/Brent – Nothing to report President’s Report – Monica/Casey – Nothing to report Committees: Traditions – Cicely - Nothing to report Website – Kenny & Ty - Nothing to report Advertising – Jay & Sofia - Nothing to report Social Media – Richard – Nothing to report Title Holder’s Reports: White Knight/Debutante – JJ & Jaklyn – Nothing to report; Jaklyn did inform all candidates that if they would like to come to the Silverado on a Tuesday night and hang out with her, they are more than welcome. Gay Portland’s – Sofia – Nothing to report; Sofia did invite all candidates to come to Cabin Fever tomorrow 09/24/19 at Stag PDX and hang out with her if they would like. Gay Oregon’s – Daddy Robert & Flawless – Nothing to report; Flawless did inform all candidates that they are more than welcome to perform at Legacy on Friday nights at Henry’s Tavern. Just send her your music at least one-hour prior. Prince & Princess – Vicious & Envi – Nothing to report Emperor & Empress – Daniel & Kimberly – Nothing to report; Daniel wanted to thank everyone that came out last night 09/22/19 for Announcement of Candidates. -

Nixon's Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968

Dark Quadrant: Organized Crime, Big Business, and the Corruption of American Democracy Online Appendix: Nixon’s Caribbean Milieu, 1950–1968 By Jonathan Marshall “Though his working life has been passed chiefly on the far shores of the continent, close by the Pacific and the Atlantic, some emotion always brings Richard Nixon back to the Caribbean waters off Key Biscayne and Florida.”—T. H. White, The Making of the President, 19681 Richard Nixon, like millions of other Americans, enjoyed Florida and the nearby islands of Cuba and the Bahamas as refuges where he could leave behind his many cares and inhibitions. But he also returned again and again to the region as an important ongoing source of political and financial support. In the process, the lax ethics of its shadier operators left its mark on his career. This Sunbelt frontier had long attracted more than its share of sleazy businessmen, promoters, and politicians who shared a get-rich-quick spirit. In Florida, hustlers made quick fortunes selling worthless land to gullible northerners and fleecing vacationers at illegal but wide-open gambling joints. Sheriffs and governors protected bookmakers and casino operators in return for campaign contributions and bribes. In nearby island nations, as described in chapter 4, dictators forged alliances with US mobsters to create havens for offshore gambling and to wield political influence in Washington. Nixon’s Caribbean milieu had roots in the mobster-infested Florida of the 1940s. He was introduced to that circle through banker and real estate investor Bebe Rebozo, lawyer Richard Danner, and Rep. George Smathers. Later this chapter will explore some of the diverse connections of this group by following the activities of Danner during the 1968 presidential campaign, as they touched on Nixon’s financial and political ties to Howard Hughes, the South Florida crime organization of Santo Trafficante, and mobbed-up hotels and casinos in Las Vegas and Miami. -

![CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present](https://docslib.b-cdn.net/cover/8733/chairmen-of-senate-standing-committees-table-5-3-1789-present-978733.webp)

CHAIRMEN of SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–Present

CHAIRMEN OF SENATE STANDING COMMITTEES [Table 5-3] 1789–present INTRODUCTION The following is a list of chairmen of all standing Senate committees, as well as the chairmen of select and joint committees that were precursors to Senate committees. (Other special and select committees of the twentieth century appear in Table 5-4.) Current standing committees are highlighted in yellow. The names of chairmen were taken from the Congressional Directory from 1816–1991. Four standing committees were founded before 1816. They were the Joint Committee on ENROLLED BILLS (established 1789), the joint Committee on the LIBRARY (established 1806), the Committee to AUDIT AND CONTROL THE CONTINGENT EXPENSES OF THE SENATE (established 1807), and the Committee on ENGROSSED BILLS (established 1810). The names of the chairmen of these committees for the years before 1816 were taken from the Annals of Congress. This list also enumerates the dates of establishment and termination of each committee. These dates were taken from Walter Stubbs, Congressional Committees, 1789–1982: A Checklist (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1985). There were eleven committees for which the dates of existence listed in Congressional Committees, 1789–1982 did not match the dates the committees were listed in the Congressional Directory. The committees are: ENGROSSED BILLS, ENROLLED BILLS, EXAMINE THE SEVERAL BRANCHES OF THE CIVIL SERVICE, Joint Committee on the LIBRARY OF CONGRESS, LIBRARY, PENSIONS, PUBLIC BUILDINGS AND GROUNDS, RETRENCHMENT, REVOLUTIONARY CLAIMS, ROADS AND CANALS, and the Select Committee to Revise the RULES of the Senate. For these committees, the dates are listed according to Congressional Committees, 1789– 1982, with a note next to the dates detailing the discrepancy. -

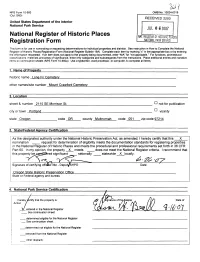

Vv Signature of Certifying Offidfel/Title - Deput/SHPO Date

NPSForm 10-900 OMBNo. 10024-0018 (Oct. 1990) RECEIVED 2280 United States Department of the Interior National Park Service JUL 0 6 2007 National Register of Historic Places m . REG!STi:ffililSfGRicTLA SES Registration Form NATIONAL PARK SERVICE — This form is for use in nominating or requesting determinations for individual properties and districts. See instruction in How to Complete the National Register of Historic Places Registration Form (National Register Bulletin 16A). Complete each item by marking "x" in the appropriate box or by entering the information requested. If an item does not apply to the property being documented, enter "N/A" for "not applicable." For functions, architectural classifications, materials and areas of significance, enter only categories and subcategories from the instructions. Place additional entries and narrative items on continuation sheets (NPS Form 10-900a). Use a typewriter, word processor, or computer, to complete all items. 1. Name of Property historic name Lone Fir Cemetery other names/site number Mount Crawford Cemetery 2. Location street & number 2115 SE Morrison St. not for publication city or town Portland vicinity state Oregon code OR county Multnomah code 051 zip code 97214 3. State/Federal Agency Certification As the designated authority under the National Historic Preservation Act, as amended, I hereby certify that this X nomination __ request for determination of eligibility meets the documentation standards for registering properties | in the National Register of Historic Places and meets the procedural and professional requirements set forth in 36 CFR [Part 60. In my opinion, the property _X_ meets __does not meet the National Register criteria. -

Opposing Views Attachment #1

North Fork Siuslaw LMP Appendix F, Table F-2 (cont.) Appendix F, Table F-2 Continued The following attachments from Dick Artley represent opposing views, with various themes: Attachment 1-timber harvest activities (p. 1), attachment 4-roads (p. 69), attachment 8-fire benefits (p. 125), attachment 9-use of glyphosate (p. 155), attachment 11-wildland-urban fire (p. 259), attachment 15-best science (p. 281), and attachment 18-herbicide label directions (p. 295). All these attachments are included in this document, and are a considered a continuation of Appendix F, Table F-2. After each opposing view in each attachment, a Forest Service (FS) response is included. Opposing Views Attachment #1 Scientists Reveal the Natural Resources in the Forest are Harmed (and some destroyed) by Timber Harvest Activities Note to the Responsible Official who reads these opposing views: There are negative effects caused by nearly all actions … this includes the actions necessary to harvest trees. The public deserves to consider projects proposed to occur on their land with the knowledge of the pros and cons of the project. The Responsible Official will find that none of the literature sources for the opposing views is specific to this project. Information contained in books and/or scientific prediction literature is never specific to individual projects. They describe cause and effects relationships that exist when certain criteria are met … at any location under the vast majority of landscape characteristics. Indeed, the literature in the References section of the draft NEPA document for this project is not specific to the project yet its used to help design this project. -

Springfield News

OnlvorBliyolOroBon Dol)t 01 juuuiu I JrlrL SPRINGFIELD NEWS (Hint Koirniry it. IMI.U 4 irliifttl I. 1mkii, ltrin1-nultorum- SPRINGFIELD, LANE COUNTY, OREGON, THURSDAY, MAY 24, 1917 VOL. XVI. NO. r rt ol t'nnxrn of M rli, my 34 $48 A MONTH FOR WIDOW INTERNED GERMANS TAKE EXERCISE SPUDS SAID TO BE ROTTEN CHRISTIAN CHURCH NO ONE 15 .vMri. W. P. Howill Hat 6077.34 Oe W. B. Cooper Wants His Money Any. EXEMPT Allan for her and Children. way? E, E. Morrison la Defendant MPROVEMENTS 10 FmyilKhi a month will bo W. B. Cooper Is plaintiff In a suit NOW; ALL BETWEEN I A. Mm U. V. Howell, by the stai filed early this week in circuit court Industrial u cell! cut commission which against E. E. Morrison, of Springfield li.vi iii.ulo nwtird in the claim for com In which ho seeks tho recovery of tho BE FINISHED 500 pcmii'ii I; (hu froth of Wm. K. sum of $2046.69, alleged duo on a 21 AND 30 TO Itowpll a ;r'irlitf resident, win quantity of potatoes which tho plain IN tli.O on May f tiMii Iho result of lo tiff sold him. 1 rrculvcd it no Booth-Kell- sa When asked about the suit, Mr. Prooonto Dlfforont Be Siruoturo mill n iMCDnili-- 1G, JMfl. Morrison stated that it really was not Exemptions to Determined Than It Did Mr, Howell loft u widow mid throo hlc affair at all since ho bad been act- After Completion of Regis- ing only as an agent a company Six Wookar Ago. -

Special 75Th Anniversary Issue

NIEMAN REPORTS SUMMER/FALL 2013 VOL. 67 NO. 2-3 Nieman Reports The Nieman Foundation for Journalism Harvard University One Francis Avenue Cambridge, Massachusetts 02138 VOL. 67 NO. 2-3 SUMMER-FALL 2013 TO PROMOTE AND ELEVATE THE STANDARDS OF JOURNALISM 75 TH ANNIVERSARY ISSUE THE NIEMAN FOUNDATION AT HARVARD UNIVERSITY Special 75th Anniversary Issue Agnes Wahl Nieman The Faces of Agnes Wahl Nieman About the cover: British artist Jamie Poole (left) based his portrait of Agnes Wahl Nieman on one of only two known images of her—a small engraving from a collage published in The Milwaukee Journal in 1916—and on the physical description she provided in her 1891 passport application: light brown hair, bluish-gray eyes, and fair complexion. Using portraits of Mrs. Nieman’s mother and father as references, he worked with cut pages from Nieman Reports and from the Foundation’s archival material to create this likeness. About the portrait on page 6: Alexandra Garcia (left), NF ’13, an Emmy Award-winning multimedia journalist with The Washington Post, based her acrylic portrait with collage on the photograph of Agnes Wahl Nieman standing with her husband, Lucius Nieman, in the pressroom of The Milwaukee Journal. The photograph was likely taken in the mid-1920s when Mrs. Nieman would have been in her late 50s or 60s. Garcia took inspiration from her Fellowship and from the Foundation’s archives to present a younger depiction of Mrs. Nieman. Video and images of the portraits’ creation can be seen at http://nieman.harvard.edu/agnes. A Nieman lasts a year ~ a Nieman lasts a lifetime SUMMER/FALL 2013 VOL. -

NPRC) VIP List, 2009

Description of document: National Archives National Personnel Records Center (NPRC) VIP list, 2009 Requested date: December 2007 Released date: March 2008 Posted date: 04-January-2010 Source of document: National Personnel Records Center Military Personnel Records 9700 Page Avenue St. Louis, MO 63132-5100 Note: NPRC staff has compiled a list of prominent persons whose military records files they hold. They call this their VIP Listing. You can ask for a copy of any of these files simply by submitting a Freedom of Information Act request to the address above. The governmentattic.org web site (“the site”) is noncommercial and free to the public. The site and materials made available on the site, such as this file, are for reference only. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals have made every effort to make this information as complete and as accurate as possible, however, there may be mistakes and omissions, both typographical and in content. The governmentattic.org web site and its principals shall have neither liability nor responsibility to any person or entity with respect to any loss or damage caused, or alleged to have been caused, directly or indirectly, by the information provided on the governmentattic.org web site or in this file. The public records published on the site were obtained from government agencies using proper legal channels. Each document is identified as to the source. Any concerns about the contents of the site should be directed to the agency originating the document in question. GovernmentAttic.org is not responsible for the contents of documents published on the website. -

Copyright by Hervey Amsler Priddy 2013

Copyright by Hervey Amsler Priddy 2013 The Dissertation Committee for Hervey Amsler Priddy Certifies that this is the approved version of the following dissertation: UNITED STATES SYNTHETIC FUELS CORPORATION: Its Rise and Demise Committee: David M. Oshinsky, Supervisor Henry W. Brands Mark A. Lawrence Michael B. Stoff Francis J. Gavin David B. Spence R. Hal Williams UNITED STATES SYNTHETIC FUELS CORPORATION: Its Rise and Demise Hervey Amsler Priddy, B.B.A.; M.B.A.; M.A. Dissertation Presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School of The University of Texas at Austin in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree of Doctor of Philosophy The University of Texas at Austin May 2013 Dedication To the Future: Jackson Priddy Bell Eleanor Amsler Bell Leighton Charles Priddy In Memory of: Ashley Horne Priddy Acknowledgments This project began in 1994, when I returned to school to pursue a master of arts in American history at Southern Methodist University, where a beautiful friendship developed with historian and Professor R. Hal Williams. In classes I took under Hal, I found his enthusiasm and passion for history infectious. When it came time to select the subject for my thesis, I was compelled that the topic had to be the United States Synthetic Fuels Corporation (SFC), where I had worked from 1980-82, and that Hal must be my advisor. That academic paper was completed in 1999 for the MA degree, but it was obvious to me at that time that I had barely scratched the surface of the subject. It seemed to me a superb dissertation topic, with much remaining to be discovered. -

The City That Works: Preparing Portland for the Future

The City That Works: Preparing Portland for the Future League of Women Voters of Portland Education Fund September 2019 Contents Section 1. Introduction and Purpose of Report ................................................................................ 1 Section 2. Roles of a City Government ............................................................................................ 2 Section 3. Relationships with Surrounding Governments .............................................................. 3 Section 4. Criteria for Evaluating Governmental Effectiveness ...................................................... 5 Section 5. Types of City Government Structures ............................................................................. 6 Section 6. Brief History of Portland’s Government Structure ......................................................... 9 Table 1. Elective Attempts to Change City Structure ................................................................. 10 Table 2. Population Trends ......................................................................................................... 12 Section 7. Current City Bureau Structure ....................................................................................... 12 Table 3. Bureau Assignments as of July 2019 ............................................................................. 13 Section 8. Strengths and Weaknesses of the Commission Form ................................................... 14 Strengths .....................................................................................................................................