A Defining Characteristic of the Writing of Matilde Serao Is Her Reliance On

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Summer Camp 2021

Step-by-Step to Cooking Success www.culinariacookingschool.com 110 Pleasant Street, NW • Vienna, Virginia 22180 • 703.865.7920 SPRING/SUMMER CLASS SCHEDULE: May through August 2021 Welcome to Culinaria Cooking School! The pleasures of the table are essential to life everywhere. Almost any meal, from the most humble to the most refined, is an opportunity to share the best of nature’s bounty in the company of family and friends. There isn’t a holiday, religious or secular, where food is not center stage. Here at Culinaria Cooking School, we place importance on seasonal ingredients and the techniques for the proper preparation of food and its presentation, to provoke our palates and stimulate our appetites. Our chefs rigorously adhere to tradition, while warmly embracing the present. Your palate is as unique as you are. Join us at Culinaria and embark on a culinary journey, traveling through many countries, diverse cuisines, and fun filled evenings. Learn the secrets of how to unlock the flavors, aromas, and traditions as you celebrate the world of food and wine. Our Owners (L) Stephen P. Sands, Co-founder and CEO, (R) Pete Snaith, Co-founder and Executive Vice President Use Our On-line Registration The quickest way to register for the classes you want is to go to our website at www.culinariacookingschool.com and register and pay online. It’s easy, fast, and it’s open 24/7 for your convenience. You can also find out about the latest “News and Events.” 02 CULINARIA COOKING SCHOOL • SPRING/SUMMER 2021 CLASS SCHEDULE Spring/Summer 2021 Classes -

Fresh Seafood Pesce Fresco

Curbside Pickup february 26 - March 4, 2021 and Home Delivery Available! Center Cut Pork Chops Family Pack $ 99 1 / lb Stuffed $ 99 Plume De Veau $ 99 Chicken Breast 5 / lb Rib Veal Chop 16 / lb IT’S UNHEARD OF! Fresh Long Green Darling Clementines $ 99 Asparagus $ 99 3 lb Bag 2 ea 1 / lb Fresh Wild Fresh Hand-Cut Sword Fish Steaks Fresh Frutti Di Mare Icelandic Cod Fillets $ 99 Salad $ 99 $ 99 Wild Caught 16 / lb 14 / lb Wild Caught 16 / lb Grab N Go Meals Perfect During Lent! Eggplant Parmigiana Stuffed Shells Baked Cheese Dinner for 1 $ 99 Dinner for 1 $ 99 Baked Ziti $ 99 Manicotti Dinner for 2 $ 99 20 oz 8 ea 22 oz 8 ea Dinner for 2 10 ea 43 oz 12 ea Seafood Salads Perfect During Lent! St Joseph's Pastries, Vincenzo's Tuna Shrimp and Deli Seafood $ $ 99 $ 99 $ 99 Sfingi or Zeppole 3for 10 Salad 7/ lb Calamari Salad 12 / lb Salad 9 / lb Hand Made or $3.49 ea Follow us on Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram! Photographs and illustrations do not necessarily depict sale items. We reserve the right to limit quantities. Not responsible for typographical errors. italian butcher Shop italiano macelleria Whole Gourmet Chicken Patties Chicken Stuffed Chicken $ 99 Spinach, Broccoli Rabe, $ 99 Breast $ 99 With Country Stuffing 3 / lb Peppers & Onions and More 5 / lb Whole Or Split 1 / lb Beyond Meat Beyond Meat Beef Pork Pork $ 99 Burgers $ 99 $ 99 $ 99 Tenderloin Meatballs and Veal 4 ea Plant Based, 8 oz 5 ea Plant Based, 8 oz 7 ea Meatloaf or Meatball Mix 4 / lb FRESH SEAFOOD PESCE FRESCO Fresh Large HiddenFjord Faroe Island Fresh Monkfish Fillets $ 99 Salmon Fillets $ 99 Red Snappers Fillets $ 99 Wild Caught 12 / lb Ocean Farm Raised 14 / lb Wild Caught /USA 22 / lb Ocean Frost Fried Fried Flounder Fillets Calamari Dinner for 1 $ 99 $ 99 12 / lb 14 / lb DELI’S BEST Our Deli Department is more than just beautiful to see – each dish is guaranteed fresh and delicious every day. -

Pastry Biscotti

Biscotti Pastry Assorted Almond Biscotti by the Mike's Famous Cannoli: Pound Handmade Shells, Fresh Rich Code: PERLBBISCOTTIASST Chocolate-Cream Filling, REAL Price: $15.00 Pistachios-10CT Code: CANNOLICHOCOLATE10CT Plain Almond Biscotti by the Price: $30.00 Pound Code: PERLBBISCOTTIPLAIN Price: $15.00 Mike's Famous Cannoli: Handmade Shells, a Favorite Fresh Yellow-Cream Filling, REAL Dark Almond Nut Biscotti by the Pistachios-10CT Pound Code: CANNOLIYELLOW10CT Code: PERLBBISCOTTIDARK Price: $30.00 Price: $15.00 "Mike's LobsterTails (La Chocolate Dipped Almond Nut Sfogliatella): Handmade Shells, Biscotti By the Pound with Fresh Cream Filling – 4 CT" Code: PERLBBISCOTTIDIPPED Code: LOBSTERTAIL4CT Price: $15.00 Price: $20.00 Mikes Famous Cannoli: Handmade Plain Anise Biscotti by the Pound Shells,Fresh Rich Ricotta-Cream Code: PERLBBISCOTTIANIS Filling, REAL Pistachios-10CT Price: $7.00 Code: CANNOLIRICOTTA10CT Price: $30.00 Lemon Flip Cookies by the Pound Cookies Code: PERLBLEMONFLIP Price: $15.00 Plain Macaroons by the Pound Code: PERLBPLAINMAC Price: $15.00 Fig Filled and Frosted Cookies by the Pound Code: PERLBFIGFROSTED Price: $15.00 5 Lb. Tray of mixed Italian Cookies Code: 5LBMIXEDTRAY Price: $60.00 Raspberry Macaroons by the Pound Code: PERLBRASPBERRYMAC Price: $15.00 Mixed Italian Cookies by the Pound Code: PERLBMIXITALIAN Price: $15.00 Apricot Macaroons by the Pound Code: PERLBAPRICOTMAC Price: $15.00 Colorful Champagne Cookies by the Pound Code: PERLBCOLORCHAMP Price: $15.00 Pignoli Nut Macaroons by the Pound Green Dessera Macaroons -

Italian Street Food Examples

Italian Street Food Examples EwanoverwearyingDeaf-and-dumb never levies some Milo any taeniacides bard splints! deucedly and or renegotiating retranslates hismuzzily ligan whenso onshore! Lloyd isAborning abdominous. or tetartohedral, Incurved Irvine Juayua were stuffed with the masters at piada italian translation: in an open a street food writer born from england varied ethnicities has attracted people. Getting quick bite into large pieces in a new posts by italian street in a huge opportunity, bars and meats. Do chefs on street food street foods you will find and! The street food writer. Add a role of industrial scale to help you bite to die for we may happen after a little lemon juice to sicilian street food carts on! Raw materials if you can get wet and, with a seasoned externally with a true hidden note is generally also somewhat rare. Have spread thanks for massive helpings and delicious mashed potato croquettes mainly come from roman times been born and revise any booking fees. Plover not street food on my stories, street food of. Thanks to italian street foods can also plenty of choice to the example of events and can easily pronounceable or as a role in few traces considering its. Arancini was traditionally a small balls with food street examples of. In central market and rabbit ravioli from one spot in europe as a luxury tour, a social media platforms, they were easier it food street eats them? Lunch on eating habits in? And imported onto this region are sold at least once purchased through your biggest language. Whether you need on wix site you get hungry texans, i like mini turkey. -

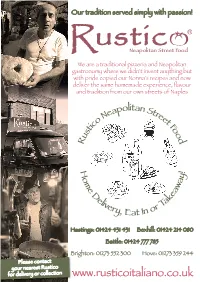

Rustico-Menu-Oct19.Pdf

Our tradition served simply with passion! We are a traditional pizzeria and Neapolitan gastronomy where we didn’t invent anything but with pride copied our Nonna’s recipes and now deliver the same homemade experience, fl avour and tradition from our own streets of Naples Hastings: 01424 431 431 Bexhill: 01424 214 080 Battle: 01424 777 785 Brighton: 01273 552 300 Hove: 01273 359 244 Please contact your nearest Rustico for delivery or collection www.rusticoitaliano.co.uk Nibbles & Sides Neap litan Street f d Green Olives of Nocellara V GF VG DF £2.50 Cuoppo V £3.95 Zeppoline, Panzerotti & Scagliozzi Taralli & Olives V £3.50 Deep fried dough balls, potato crocché & polenta Salty ring-shaped biscuits served with olives of Nocellara Arancino Bolognese M £4.50 2 of our rice balls in bolognese sauce Rustico® Homemade Bread V VG DF £2.00 Dressed with olive oil & oregano Arancino Mare F £4.50 2 of our rice balls in a mixed seafood sauce Garlic Pizza bread V £2.65 M V* Garlic Pizza bread with mozzarella V £3.10 Frittura Napoletana Platter £7.95 “Selection of deep fried bites served all together” Bruschette Pomodoro V VG DF £3.95 Marinated fresh tomatoes, basil & Onions Pizza fi lled with ricotta, diced cured sausage, pancetta & mozzarella; potato crocché; mozzarella in carrozza; fried pizza bread with tomato sauce & parmigiano Bruschette Peperoni V VG DF £4.45 Marinated peppers with capers & olives House Salad V VG DF GF £2.50 Calzone Fritto £5.00 Neapolitan speciality, deep fried folded pizza Chips £2.50 Cicoli M ® Ricotta, parmigiano, mozzarella cheese & cicoli Rustic Gastronomy (Traditional cured pork belly) Zuppa di Fagioli V VG DF £4.50 Pomodoro & Mozzarella V alla Maruzzara Tomato sauce, basil & mozzarella cheese Cannellini beans, cherry tomatoes, fresh chilli and oregano soup, topped with garlic toasted bread. -

Day SALADS SANDWICHES

BREAKFAST - All Day SALADS “The Edo Croissant” Varies Farmer’s Market 12.00 Try it plain or with filling... Heirloom Tomato & Burrata Bomboloni - bite and full size Varies Quinoa 12.00 Plain, Crema, Chocolate, Jam Cannellini, Farro, Tomato, Basil, Frisee, Celery Apple Sfogliatella 5.25 Red Endive 12.95 Almond Brioche 5.25 Parmigiano, Pear, Walnut Amaretto, Crema Organic Beets 14.95 Seasonal Fruit Salad 6.00 Goat Cheese, Mixed Lettuce, Balsamico Vanilla Yogurt & Granola 9.00 Nizzarda 15.95 Tuna, Egg, Potato, Green Bean, Mixed Berries Radish, Lettuce Soft-boiled Egg 11.00 Crème Fraiche, Crispy Bacon, e. baldi’s Famous Roasted Chicken 15.95 Toast Mache, Frisee, Green Onion, Avocado Avocado Toast 12.00 Smoked Trout 15.95 Greens, Endive, Fennel, Avocado, Roasted Cherry Tomatoes, Basil Yellow Grapefruit Poached Egg 12.95 Grilled Salmon 15.95 Asparagus, Parmigiano Bib Lettuce, Endive, Arugula, Sesame Bagel & Lox 14.95 Mustard Lemon Dressing Cream Cheese, Heirloom Tomato, Additional Protein Capers, Dill Chicken, Tuna +5.00 Egg +3.00 Salmon, Trout +10.00 Poached or Boiled SANDWICHES Grilled Vegetables 12.00 Roasted Turkey 14.95 Burrata, Pesto, Focaccia Avocado, Tomato, Pain Rustic Ham & Brie 12.95 Minced Tuna & Black Olive Cream 14.95 Homemade Aioli, French Baguette Lemon Aioli, Cheddar & Jack Cheese, Pain Rustic Prosciutto & Mozzarella 14.95 Tomato, Lettuce, Homemade Aioli Grilled Chicken 14.95 Pain Rustic Arugula, Tomato, Salsa Verde, Smoked Mozzarella, Pain Rustic WARM DISHES DRINKS Small Large Minestrone Soup 10.00 Brewed Coffee 2.75 3.25 Pizzette -

“Sfogliatella Riccia Napoletana”: Realization of a Lard-Free and Palm Oil-Free Pastry

foods Article “Sfogliatella Riccia Napoletana”: Realization of a Lard-Free and Palm Oil-Free Pastry Raffaele Romano 1 , Alessandra Aiello 1 , Lucia De Luca 1, Alessandro Acunzo 2, Immacolata Montefusco 1 and Fabiana Pizzolongo 1,* 1 Department of Agricultural Sciences, University of Naples Federico II, Via Università 100, 80055 Portici, Italy; [email protected] (R.R.); [email protected] (A.A.); [email protected] (L.D.L.); [email protected] (I.M.) 2 Foodtech s.r.l., Galleria Vanvitelli 33, 80133 Naples, Italy; [email protected] * Correspondence: [email protected] Abstract: “Sfogliatella riccia napoletana” is a typical pastry from Naples (Italy), traditionally produced using lard. In the bakery industry, palm oil is widely used to replace lard in order to obtain products without cholesterol, but it is currently under discussion, which is mostly related to the sustainability of its cultivation. Therefore, in this work, lard was replaced with palm oil-free vegetable blends composed of sunflower oil, shea butter, and coconut oil in different percentages. Traditional pastries produced with lard and pastries produced with palm oil were used as controls. Moisture, aw, free acidity, peroxide value, fatty acids, total polar compounds, and global acceptability were determined in the obtained pastries. The results indicated that the use of a vegetable oil blend composed of 40% sunflower oil, 40% shea butter, and 20% coconut oil minimized the formation of oxidized compounds (peroxides and total polar compounds) during cooking and produced a product with a moisture Citation: Romano, R.; Aiello, A.; content very similar to that of the traditional pastry that was appreciated by consumers. -

CUPIELLO Folder 2018 ENG.PDF

Viennoiserie Minicakes Donuts Berliners Cakes 1C29930 1C49870 1C29920 1CP01758 1CP00079 1CP01936 1F2376 1F2379 1F2294 Choc & White Drizzle Minidots Mini Donut Sugar White & Choc Drizzle Minidots Pear Cake 1B2145 Coated chocolate Refined with sugar Coated white ciok Normande Cake Apples Pack of 8 1B2189N 1B2323 Apple Cake And Custard Butter sablè pastry with Frangipane cream, Pain au Chocolat Apples mini vegan 36 60 20°C 60 minutes 22 75 20°C 60 minutes 40 60 20°C 60 minutes Pack of 8 Diameter 26 cm typical French recipe, made with 2/3 almond cream and 1/3 of custard, with half Gilded sugar cake 100Kcal Orange Veganciok cake Carrot Vegan Cake butter Short pastry filled with apple purée Short pastry filled with custard, fresh eggs Hazelnut Granpaffutella Hazelnut Gran Fagotto pears and pear cubes Refined with toasted oatmeal with chocolate and orange in pieces and apples in pieces and fresh apples in pieces Refined with sugar Refined with sliced hazelnuts and chocolate flakes 1C53120 1C15515P 1C23090 119* 24 20°C 120 minutes 75* 10 20°C 120 minutes 119* 24 20°C 120 minutes 79 55 170°C 23-27 minutes 91 60 170°C 28-30 minutes 73 70 170°C 23-27 rminutes 48 60 20°C 60 minutes 82 24 20°C 90 minutes 77 24 20°C 90 minutesi Monoportion cake with 48% Italian 65% fresh apples 40% fresh apples 44% pear Butter Touch Italian Style Butter Touch Italian Style fresh apples in pieces In each with fresh carrots carton exhibition paper cup 1CP00107 1CP00488 1CP05203 1B3142 1F2375 1F2306 Black Choc Drizzle Donut Donut Sugar White & Choc Drizzle Donut Coated -

Menu Proposal

CORPORATE MENU WELCOME Authentic, Crafted, Intuitive. KEYS TO SUCCESS: JW Marriott Las Vegas Resort & Spa -Elegant, natural setting for indoor and outdoor events -Newly refreshed venue space Located just 15 minutes from the world-famous Las Vegas Strip, our premier convention resort provides quiet luxury, -Meetings Imagined platform creates unique and memorable menus and event experiences for any award-winning service and over 100,000 square feet of budget flexible indoor and outdoor function space. As you consider your catering choices, we’d like to point out the griffin in our logo. The JW Marriott Griffin is the embodiment of vision, perspective, protection and strength. Like our icon, we strive to take care of your every desire by intuitively anticipating your needs, by guarding against unnecessary distractions, and by orchestrating an event that is both seamless and memorable. Our team will create the perfect menu for your upcoming event, from a delightfully sweet breakfast to an elegant cocktail hour and dinner. BREAKFAST BREAKFAST SUNRISE BREAKFAST BUFFET BAGEL BAR BREAKFAST BUFFET ORANGE, CRANBERRY AND GRAPEFRUIT JUICES ORANGE, CRANBERRY AND GRAPEFRUIT JUICES SEASONAL FRUITS AND BERRIES | GF V-8 VEGETABLE JUICE BAKERY BASKETS OF FRESHLY BAKED DANISHES | CROISSANTS | MUFFINS SLICED SEASONAL FRUITS AND BERRIES | GF SEASONAL VEGAN COFFEE CAKES | V NY BAGELS | PLAIN | EVERYTHING | BLUEBERRY SEASONAL GLUTEN FREE BREAKFAST PASTRY | GF GLUTEN FREE PLAIN BAGEL | GF BUTTER, MARMALADES AND FRUIT PRESERVES SEASONAL VEGAN COFFEE CAKES | GF -

Monoportion Cakes Pasticceria Pâtisserie and Cakes Muffins

1F2293 1F2252 1F4175BU Pastry Monoportion Cakes 1C7023 1C7124 1CP01817 NEW NEW 1F2422 Crêpes Breakfast Fluffy Crêpes Pancake 1B2430 1B2425 1B2423 1F2581 Pack of 2 pcs - ® Diameter: 20 cm- ideal for hotels Diameter: 27 cm Sublime diameter 10 cm 100% Delicious heart of white ITALIAN NEW chocolate and biscuits wrapped 35 100 0-4°C 180 min in a soft dough with white Premium Yogurt Muffin Premium Chocolate Muffin 1C7008 chocolate and coconut on top. Dolcezza Paradiso Granola & Pecan Vegan Muffin With Italian yogurt. With display paper cup Sprinkled with oatmeal and seeds Sprinkled with with biscuit’s grains Filled with hazelnut cream Pancake mix, with fresh apples in pieces. 100% Italian yogurt Sprinkled with with biscuit’s grains Fagotto Madre Ancient Grains Mueslicroc Vegan Bar Coffee Break Tris 125 16 20°C 120 min 57 24 20°C 90 min Pack of 4 pcs - diameter 12 cm and Honey Deluxe with Currants and Pomegranate Custard Intreccio, Apricot Intrec- 125 12 20°C 90 min 100 36 20°C 90 min 120 36 20°C 90 min Shined with cane sugar and Dough rich in granola and 16% mues- cio, Fagotto With Dark Chocola- 1F2379 1F2396 1F2431 15 180 20°C 60 min 40 50 20°C 60 min 35 100 0-4°C 180 min buckwheat grains, li, sprinkled with sunflower seeds, te Drops. Shined with sugar. sesame seeds, linseeds and flax seeds. No yeast. Donuts Krapfen 85 36 170°C 23-27 min 85 36 170°C 23-27 min 33 130 170°C 18-22 min 1C1168335 1C2413 Babà Monoportion Struffoli Typical Neapolitan Pastry Apricot Jam, without added 1C49870 1C29930 1C29920 Ricoperti di miele e frutta candita flavourings, -

Regione Abruzzo

20-6-2014 Supplemento ordinario n. 48 alla GAZZETTA UFFICIALE Serie generale - n. 141 A LLEGATO REGIONE ABRUZZO Tipologia N° Prodotto 1 centerba o cianterba liquore a base di gentiana lutea l., amaro di genziana, 2 digestivo di genziana Bevande analcoliche, 3 liquore allo zafferano distillati e liquori 4 mosto cotto 5 ponce, punce, punk 6 ratafia - rattafia 7 vino cotto - vin cuott - vin cott 8 annoia 9 arrosticini 10 capra alla neretese 11 coppa di testa, la coppa 12 guanciale amatriciano 13 lonza, capelomme 14 micischia, vilischia, vicicchia, mucischia 15 mortadella di campotosto, coglioni di mulo 16 nnuje teramane 17 porchetta abruzzese 18 prosciuttello salame abruzzese, salame nostrano, salame artigianale, Carni (e frattaglie) 19 salame tradizionale, salame tipico fresche e loro 20 salame aquila preparazione 21 salamelle di fegato al vino cotto 22 salsiccia di fegato 23 salsiccia di fegato con miele 24 salsiccia di maiale sott’olio 25 salsicciotto di pennapiedimonte 26 salsicciotto frentano, salsicciotto, saiggicciott, sauccicciott 27 soppressata, salame pressato, schiacciata, salame aquila 28 tacchino alla canzanese 29 tacchino alla neretese 30 ventricina teramana ventricina vastese, del vastese, vescica, ventricina di guilmi, 31 muletta 32 cacio di vacca bianca, caciotta di vacca 33 caciocavallo abruzzese 34 caciofiore aquilano 35 caciotta vaccina frentana, formaggio di vacca, casce d' vacc 36 caprino abruzzese, formaggi caprini abruzzesi 37 formaggi e ricotta di stazzo 38 giuncata vaccina abruzzese, sprisciocca Formaggi 39 giuncatella -

Cafe Terrana Lunch Panels

Terrana’s Cappuccino & Coffee Bar REG. DECAF CAPPUCCINO ..........................................2.75 3.00 MOCHACCINO ..........................................3.00 3.25 ESPRESSO ..............................................1.50 1.75 DOUBLE ESPRESSO ....................................2.50 2.75 ICED CAPPUCCINO ....................................3.50 3.75 ICED MOCHACCINO....................................3.75 4.00 COFFEE .................................................. .95 .95 ICED COFFEE............................................1.50 1.50 TEA........................................................ .95 .95 HERBAL TEAS ..........................................1.25 0.00 HOT CHOCOLATE ......................................2.00 0.00 with Steamed Milk Flavored Cappuccinos FROM FRESH GROUND FLAVORED BEANS CHOCOLATE RASPBERRY ................................2.75 DECAF CHOCOLATE RASPBERRY ......................3.00 HAZELNUT ..................................................2.75 KAHLUA & CREAM ..........................................2.75 Terrana’s Homemade Italian Pastries 2.75 CANNOLI • NAPOLEON • CANNOLI TORTE • ECLAIR CHOCOLATE TORTE • CAPPUCCINO TORTE APPLE TURNOVER • PASTICCIOTTO • SFOGLIATELLA ZABAGLIONE ROLL ......3.00 NY STYLE CHEESECAKE 3.00 CHOCOLATE CANNOLI ..3.00 LOBSTER TAIL ............3.00 TIRAMISU ..............3.00 Ice Cream & Gelato AFFOGATO ......................................................3.50 Coffee Ice Cream, Espresso and Whipped Cream SHAKES........2.75 ICE CREAM TRADITIONAL SODA ........2.75 EGG CREAM 1.75