Embodied Rhythm Lukas Ligeti

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

General Guidelines for Guest Editor

1 Vol 15 Issue 01 – 02 January 2007 The Burkina Electric Project and Some Thoughts About Electronic Music in Africa Lukas Ligeti [email protected] http://www.lukasligeti.com Keywords Burkina Electric Project, electronic music, Africa, electronics and computer technology Abstract This paper is an updated summary of a presentation I gave at the Unyazi Electronic Music Festival in Johannesburg, South Africa in 2005. Burkina Electric, founded in 2004, is an ensemble featuring two musicians (singer Mai Lingani and guitarist Wende K. Blass) and two dancers (Hugues Zoko and Idrissa Kafando) from Burkina Faso; the German pop music pioneer Pyrolator on electronics (both audio and visual); and myself on electronics and drums. Our objective is to create and perform original music combining the traditions of Burkina Faso with the world of DJ/club/dance electronica. In so doing, we build bridges between African and Western cultures, especially in the domains of pop/youth culture and experimental music. Burkina Electric's debut CD, Paspanga, was recently released for the Burkinabè market. By using elements of Burkinabè traditional music, including rhythms not usually heard in contemporary urban music, plus rhythms of our own creation, we aim to enlarge the vocabulary of “grooves” in the club/dance landscape; the dancers help audiences interpret these unusual rhythmic patterns. Sonorities and structural models of West African music are transferred to electronics and reassembled and processed in various ways. Rather than superimposing drum programming on top of an African traditional structures, we compose music that aims to organically confront and combine Africa and Occident, and tradition and experiment, while maintaining the particular sensibilities of both worlds. -

Burkina Electric

BURKINA ELECTRIC FUSION / ELECTRONICA (BURKINA FASO - AUSTRIA -US - IVORY COAST) “An irresistible brew of West African music and electronica” - New York Times DISCOGRAPHY: Hailed by the New York Times as an “irresistible brew of West African PASPANGA music and electronica,” Burkina Electric is the first electronic music 2009, CANTALOUPE RECORDS group from Burkina Faso, in the deep interior of West Africa. ”The band’s energy onstage is infectious” - Based in Ouagadougou, Burkina Faso’s capital, it is, at the same time, Songlines Magazine an international band, with members living in New York, U.S.A. and Ouaga. STREAMING: Burkina Electric’s music combines the traditions and rhythms of • soundcloud.com/burkina-electric Burkina Faso with contemporary electronic dance culture, making it a trailblazer in electronic world music. A diverse and talented group con- sisting of four musicians and two dancers, they collectively participate in the creative process and represent disparate musical genres and Booking Scandinavia: d to the sounds from across the globe. on le c f Marisa Segala e t S +45 / 25 61 82 82 Rather than recycling well-known rock and funk rhythms, Burkina [email protected] Electric seeks to enrich the fabric of electronic dance music by using www.secondtotheleft.com unusual rhythms that are rarely heard and little-known even in much of Skype: marisa.segala.bennett Africa. This includes ancient rhythms of the Sahel, such as the Mossi peoples’ Ouaraba and Ouenega, but also new grooves of their own creation. The band invites you to discover that these exotic rhythms groove at least as powerfully as disco, house, or drum & bass! The group creates a unique and refreshing musical world that is all their own by incorporating sounds of traditional instruments and found sounds recorded in Burkina Faso. -

AMN Interviews: Lukas Ligeti – Avant Music News Avant Music News

11/2/2020 AMN Interviews: Lukas Ligeti – Avant Music News Avant Music News A source for news on music that is challenging, interesting, different, progressive, introspective, or just plain weird AMN Interviews: Lukas Ligeti JUNE 10, 2015 ~ MIKE (hps://avantmusicnews.files.wordpress.com/2015/06/5389294442_65b8ed8367.jpg)Compo ser and percussionist Lukas Ligeti (hp://lukasligeti.com/) will celebrate his 50th birthday with two nights of premieres: June 14th at Roulee, and June 11th at the Austrian Cultural Forum. The concert series opens June 11th at the ACFNY, with performances of Lukas’ solo and small ensemble works (performers include Thomas Bergeron, Candy Chiu, Jennifer Hymer, Ben Reimer, David Cossin, and others), and premiere pieces for Lukas’ new classical/indie rock band, Notebook. The festival culminates June 14th at Roulee featuring Lukas’ music for chamber orchestra. Program includes several world premieres, as well as U.S. and New York City premieres, performed by the fresh, contemporary-collective Ensemble mise-en conducted by Oliver Hagen, pianist Vicky Chow, and others. Recently, he took time to answer a few questions from AMN. You are a truly international composer and performer, in the sense that you have followings on at least three continents and have been influenced by the music thereof. How did you develop this global approach to music? My whole life story, even my family history, has predestined me to exist less in any specific culture than in the spaces between them. I was born in Austria to parents who had fled from Hungary. But, being jews, they were not entirely clearly Hungarians, either – not, at least, since having experienced the holocaust. -

Introduction — Unyazi.” “Unyazi” Special Issue, Leonardo Electronic Almanac Vol

1 Vol 15 Issue 01 – 02 January 2007 Introduction UNYAZI Jürgen Bräuninger Associate Professor School of Music University of KwaZulu-Natal Durban 4041 South Africa [email protected] http://www.music.ukzn.ac.za Keywords Unyazi, electronic music, computer music, festival, symposium, workshops, concerts, lectures, South Africa, 2005 Abstract A summary of the first South African electro-acoustic music symposium/festival which took place in Johannesburg, 1-4 September 2005, reviewing its concerts, workshops, and lectures by local and international composers and researchers. Introduction South Africa is famous for many things but certainly not for its electronic music production. However, 35 years after the first electroacoustic music studio was constructed around an ARP-2500 synthesizer at the University of Natal, a small but dedicated number of computer music artists has evolved in the Johannesburg-Cape Town- Durban triangle, and university music departments across the country are now offering music technology courses. In 2003, feeling that it was about time to map the scene and to give it a boost simultaneously, NewMusicSA (the South African section of the International Society for Contemporary Music) proposed an electronic music symposium/festival with Dimitri Voudouris in charge of proceedings. After two years of networking, planning and fundraising, UNYAZI (the isiZulu word for lightning) took place 1-4 September 2005 at all three venues of the Wits Theatre complex in Johannesburg, assembling an illustrious group of local and international electronic music practitioners. Diversity was the obvious festival concept. Halim El-Dabh, who as early as 1944 experimented with a wire recorder in Cairo's radio station, presented some of his vintage works. -

György Ligeti and the Future of Maverick

! György Ligeti and the Future of Maverick Modernity Conference soundSCAPE Festival, 14 July 2014 www.soundSCAPEfestival.org ! 08:00 Check In at Auditorium Città di Maccagno - via Valsecchi 23, Maccagno (VA) !light breakfast pastries, coffee and water will be available for conference presenters 09:15 Welcome Address !Nathanael May, Artistic Director; soundSCAPE !Session 1: Analysis 09:30 Ligeti’s Aventures and Nouvelles Aventures: An exploration of musical technique !Benjamin Levy, Assistant Professor of Music Theory; University of California, Santa Barbara 10:00 The Transcendental Perception of the Piano Concerto (1st movement) by György Ligeti !Lee Kar Tai Phoebus, Teaching Assistant; The Chinese University of Hong Kong 10:30 Timbre and Space in Ligeti's Music !Lukas Haselboeck, Assistant Professor for Music Analysis; University of Music Vienna !11:00 ~ break ~ !Session 2: Performance 11:30 Poème Symphonique: A digital reconstruction !Jason Charney, Bowling Green State University 12:00 Performing Ligeti’s Violin Concerto: A work for the present day !Jane Roper, Professor for Academic Studies; Royal College of Music 12:30 Ligeti and Performance Skills !Peter Susser, Director of Undergraduate Musicianship; Columbia University !13:00 ~ lunch ~ not provided !Session 3: Philosophies 14:30 Codes, Constraints, and the Loss of Control in Ligeti’s Keyboard Works !Amy Bauer, Associate Professor of Music; University of California, Irvine 15:00 Ligeti the Maverick? An Examination of Ligeti’s Ambivalent Role in Contemporary Music !Mike Searby, Principal -

The World of Music

Contents •1 the world of music vol. 45(2) - 2003 Traditional Music and Composition For György Ligeti on his 80th Birthday Max Peter Baumann Editor Jonathan Stock Co-Editor Ashok D. Ranade Christian Utz Guest Editors Tina Ramnarine Book Review Editor Gregory F. Barz CD-Review Editor VWB – Verlag für Wissenschaft und Bildung Berlin 2003 2• the world of music 44 (2) - 2002 Contents •3 Journal of the Department of Ethnomusicology Otto-Friedrich University of Bamberg Vol. 45 (2) – 2003 CONTENTS Traditional Music and Composition For György Ligeti on his 80th Birthday Articles Christian Utz Listening Attentively to Cultural Fragmentation: Tradition and Composition in Works by East Asian Composers . 7 Franki S. Notosudirdjo Kyai Kanjeng: Islam and the Search for National Music in Indonesia . 39 Barbara Mittler Cultural Revolution Model Works and the Politics of Modernization in China: An Analysis of Taking Tiger Mountain by Strategy . 53 Stephen Andrew Ligeti, Africa and Polyrhythm . 83 Taylor Ashok D. Ranade Traditional Musics and Composition in the Indian Context . 95 Composers’ Statements Sandeep Bhagwati Stepping on the Cracks, Or, How I Compose with Indian Music in Mind . 113 Guo Wenjing Traditional Music as Material . 125 Kim Jin-Hi Living Tones: On My Cross-cultural Dance-music Drama Dragon Bond Rite . 127 4• the world of music 44 (2) - 2002 Koo Bonu Beyond “Cheap Imitations” . 133 Lukas Ligeti On My Collaborations with Non-Western Musicians and the Influence of Technology in These Exchanges 137 Qin Wenchen On Diversity . 143 Takahashi Ysji Two Statements on Music . 147 Book Reviews (Tina K. Ramnarine, ed.) From the Book Reviews Editor . -

11-21-09 Percussion Ensemle Prog

Williams College Department of Music Williams Percussion Ensemble Noise/Signal Matthew Gold, director Zoltán Jeney impho 102/6 (1978) Alex Creighton ’10 and if i were in, on, or around (2009) * Brian Simalchik ’10 for percussion quartet Giacinto Scelsi I Riti: Ritual March The Funeral of Achilles (1962) James Romig The Frame Problem (2003) for percussion trio Elliott Sharp Saturate (1993) for baritone saxophone, electric guitar, piano, and percussion Currents - An electronic sound exploration and collaboration between Peter Wise and the Williams Percussion Ensemble Michel van der Aa Between (1997) ** for percussion quartet and soundtrack ** world premiere ** U.S. premiere Saturday, November 21, 2009 8:00 p.m. Chapin Hall Williamstown, Massachusetts Upcoming Events: See music.williams.edu for full details and to sign up for the weekly e-newsletters. 11/22: Shhh Free Sunday: Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall, 1:00 p.m. 11/30: Visiting Artist: Bösendorfer Concert–Seymour Lipkin, Chapin Hall, 8:00 p.m. 12/1: Studio Recital: Violin, Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall, 2:00 p.m. 12/1: Seymour Lipkin Piano Master Class, Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall, 4:15 p.m. 12/2: MIDWEEKMUSIC, Chapin Hall Stage, 12:15 p.m. 12/3: Class of 1960 Lecture: Prof. Elaine Sisman, Bernhard Room 30, 4:15 p.m. 12/4: Williams Symphonic Winds and Opus Zero Band, MASS MoCA, 8:00 p.m. 12/5: Service of Lessons and Carols, Thompson Memorial Chapel, 4:00 p.m. 12/6: Service of Lessons and Carols, Thompson Memorial Chapel, 4:00 p.m. 12/6: Studio Recital: Chamber Music (Winds and Strings), Brooks-Rogers Recital Hall, 7:30 p.m. -

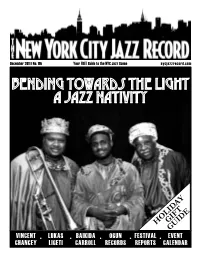

Bending Towards the Light a Jazz Nativity

December 2011 | No. 116 Your FREE Guide to the NYC Jazz Scene nycjazzrecord.com bending towards the light a jazz nativity HOLIDAYGIFT GUIDE VINCENT •••••LUKAS BAIKIDA OGUN FESTIVAL EVENT CHANCEY LIGETI CARROLL RECORDS REPORTS CALENDAR The Holiday Season is kind of like a mugger in a dark alley: no one sees it coming and everyone usually ends up disoriented and poorer after the experience is over. 4 New York@Night But it doesn’t have to be all stale fruit cake and transit nightmares. The holidays should be a time of reflection with those you love. And what do you love more Interview: Vincent Chancey than jazz? We can’t think of a single thing...well, maybe your grandmother. But 6 by Anders Griffen bundle her up in some thick scarves and snowproof boots and take her out to see some jazz this month. Artist Feature: Lukas Ligeti As we battle trying to figure out exactly what season it is (Indian Summer? 7 by Gordon Marshall Nuclear Winter? Fall Can Really Hang You Up The Most?) with snowstorms then balmy days, what is not in question is the holiday gift basket of jazz available in On The Cover: A Jazz Nativity our fine metropolis. Celebrating its 26th anniversary is Bending Towards The 9 by Marcia Hillman Light: A Jazz Nativity (On The Cover), a retelling of the biblical story starring jazz musicians like this year’s Three Kings - Houston Person, Maurice Chestnut and Encore: Lest We Forget: Wycliffe Gordon (pictured on our cover) - in a setting good for the whole family. -

Downloads, the Bandleader Composed the Entire Every Musician Was a Multimedia Artist,” He Said

AUGUST 2019 VOLUME 86 / NUMBER 8 President Kevin Maher Publisher Frank Alkyer Editor Bobby Reed Reviews Editor Dave Cantor Contributing Editor Ed Enright Creative Director ŽanetaÎuntová Design Assistant Will Dutton Assistant to the Publisher Sue Mahal Bookkeeper Evelyn Oakes ADVERTISING SALES Record Companies & Schools Jennifer Ruban-Gentile Vice President of Sales 630-359-9345 [email protected] Musical Instruments & East Coast Schools Ritche Deraney Vice President of Sales 201-445-6260 [email protected] Advertising Sales Associate Grace Blackford 630-359-9358 [email protected] OFFICES 102 N. Haven Road, Elmhurst, IL 60126–2970 630-941-2030 / Fax: 630-941-3210 http://downbeat.com [email protected] CUSTOMER SERVICE 877-904-5299 / [email protected] CONTRIBUTORS Senior Contributors: Michael Bourne, Aaron Cohen, Howard Mandel, John McDonough Atlanta: Jon Ross; Boston: Fred Bouchard, Frank-John Hadley; Chicago: Alain Drouot, Michael Jackson, Jeff Johnson, Peter Margasak, Bill Meyer, Paul Natkin, Howard Reich; Indiana: Mark Sheldon; Los Angeles: Earl Gibson, Andy Hermann, Sean J. O’Connell, Chris Walker, Josef Woodard, Scott Yanow; Michigan: John Ephland; Minneapolis: Andrea Canter; Nashville: Bob Doerschuk; New Orleans: Erika Goldring, Jennifer Odell; New York: Herb Boyd, Bill Douthart, Philip Freeman, Stephanie Jones, Matthew Kassel, Jimmy Katz, Suzanne Lorge, Phillip Lutz, Jim Macnie, Ken Micallef, Bill Milkowski, Allen Morrison, Dan Ouellette, Ted Panken, Tom Staudter, Jack Vartoogian; Philadelphia: Shaun Brady; Portland: Robert Ham; San Francisco: Yoshi Kato, Denise Sullivan; Seattle: Paul de Barros; Washington, D.C.: Willard Jenkins, John Murph, Michael Wilderman; Canada: J.D. Considine, James Hale; France: Jean Szlamowicz; Germany: Hyou Vielz; Great Britain: Andrew Jones; Portugal: José Duarte; Romania: Virgil Mihaiu; Russia: Cyril Moshkow; South Africa: Don Albert. -

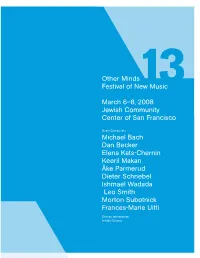

Other Minds 13 Program

Other Minds Festival of New Music March 6–8, 2008 Jewish Community Center of San Francisco Guest Composers Michael Bach Dan Becker Elena Kats-Chernin Keeril Makan Åke Parmerud Dieter Schnebel Ishmael Wadada Leo Smith Morton Subotnick Frances-Marie Uitti Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director 34 12 16 B 7 19 15 A 2 36 1 Other Minds, in association with the Djerassi Resident Artists Program and the Eugene and Elinor Friend Center for the Arts at the Jewish Community Center of San Francisco, presents Other Minds 13 Charles Amirkhanian, Artistic Director Jewish Community Center of San Francisco March 6-7-8, 2008 Table of Contents 3 Message from the Artistic Director 4 Exhibition & Silent Auction 6 Concert 1 7 Concert 1 Program Notes 10 Concert 2 11 Concert 2 Program Notes 14 Concert 3 15 Concert 3 Program Notes 20 Other Minds 13 Composers 24 About Other Minds Other Minds 13 Festival Staff 25 Other Minds 13 Performers 28 Festival Supporters A Gathering of Other Minds Program Design by Leigh Okies. Layout and editing by Adam Fong. © 2008 Other Minds. All Rights Reserved. The Djerassi Resident Artists Program is a proud co-sponsor of Other Minds Festival XIII The mission of the Djerassi Resident Artists Program is to support and enhance the creativity of artists by providing uninterrupted time for work, reflection, and collegial interaction in a setting of great natural beauty, and to preserve the land upon which the Program is situated. The Djerassi Program annually welcomes the Other Minds Festival composers for a five-day residency for collegial interaction and preparation prior to their concert performances in San Francisco. -

Lukas Ligeti Is a Composer and Percussionist Living in New York

Lukas Ligeti | Biography Transcending the boundaries of genre, composer-percussionist Lukas Ligeti has developed a musical style of his own that draws upon downtown New York experimentalism, contemporary classical music, jazz, electronica, as well as world music, particularly from Africa. Known for his non-conformity and diverse interests, Lukas creates music ranging from the through- composed to the free-improvised, often exploring polyrhythmic/polytempo structures, non-tempered tunings, and non-western elements. Other major sources of inspiration include experimental mathematics, computer technology, architecture and visual art, sociology and politics, and travel. He has also been participating in cultural exchange projects in Africa for the past 15 years. Born in Vienna, Austria into a Hungarian-Jewish family from which several important artists have come including his father, composer György Ligeti, Lukas started his musical adventures after finishing high school. He studied composition and percussion at the University for Music and Performing Arts in Vienna and then moved to the U.S. and spent two years at the Center for Computer Research in Music and Acoustics at Stanford University before settling in New York City in 1998. His commissions include Bang on a Can, the Vienna Festwochen, Ensemble Modern, Kronos Quartet, Colin Currie and Håkan Hardenberger, the American Composers Forum, New York University, ORF Austrian Broadcasting Company, Radio France, and more; he also regularly collaborates with choreographer Karole Armitage. As a drummer, he co-leads several bands and has performed and/or recorded with John Zorn, Henry Kaiser, Raoul Björkenheim, Gary Lucas, Michael Manring, Marilyn Crispell, Benoit Delbecq, Jim O’Rourke, Daniel Carter, John Tchicai, Eugene Chadbourne, and many others. -

An Examination of Lukas Ligeti's Thinking Songs

University of South Carolina Scholar Commons Theses and Dissertations Spring 2019 An Examination of Lukas Ligeti’s Thinking Songs: An Analysis of Compositional Techniques for Ligeti’s Contemporary Solo Marimba Composition Caitlin Jones Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd Part of the Theatre and Performance Studies Commons Recommended Citation Jones, C.(2019). An Examination of Lukas Ligeti’s Thinking Songs: An Analysis of Compositional Techniques for Ligeti’s Contemporary Solo Marimba Composition. (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from https://scholarcommons.sc.edu/etd/5255 This Open Access Dissertation is brought to you by Scholar Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Theses and Dissertations by an authorized administrator of Scholar Commons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. AN EXAMINATION OF LUKAS LIGETI’S THINKING SONGS: AN ANALYSIS OF COMPOSITIONAL TECHNIQUES FOR LIGETI’S CONTEMPORARY SOLO MARIMBA COMPOSITION by Caitlin Jones Bachelor of Fine Arts University of Florida, 2014 Master of Music Lee University, 2016 Submitted in Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements For the Degree of Doctor of Musical Arts in Performance School of Music University of South Carolina 2019 Accepted by: Scott Herring, Major Professor J. Daniel Jenkins, Committee Member Kunio Hara, Committee Member Tonya Mitchell, Committee Member Cheryl L. Addy, Vice Provost and Dean of the Graduate School © Copyright by Caitlin Jones, 2019 All Rights Reserved. ii DEDICATION In honor of my parents, Chip and Catherine, for always being my biggest supporters. Also, to my music teachers, from childhood piano lessons to doctoral study, for inspiring me and being a source of encouragement.