08 Ligeti 41-47

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a New Look at Musical Instrument Classification

The KNIGHT REVISION of HORNBOSTEL-SACHS: a new look at musical instrument classification by Roderic C. Knight, Professor of Ethnomusicology Oberlin College Conservatory of Music, © 2015, Rev. 2017 Introduction The year 2015 marks the beginning of the second century for Hornbostel-Sachs, the venerable classification system for musical instruments, created by Erich M. von Hornbostel and Curt Sachs as Systematik der Musikinstrumente in 1914. In addition to pursuing their own interest in the subject, the authors were answering a need for museum scientists and musicologists to accurately identify musical instruments that were being brought to museums from around the globe. As a guiding principle for their classification, they focused on the mechanism by which an instrument sets the air in motion. The idea was not new. The Indian sage Bharata, working nearly 2000 years earlier, in compiling the knowledge of his era on dance, drama and music in the treatise Natyashastra, (ca. 200 C.E.) grouped musical instruments into four great classes, or vadya, based on this very idea: sushira, instruments you blow into; tata, instruments with strings to set the air in motion; avanaddha, instruments with membranes (i.e. drums), and ghana, instruments, usually of metal, that you strike. (This itemization and Bharata’s further discussion of the instruments is in Chapter 28 of the Natyashastra, first translated into English in 1961 by Manomohan Ghosh (Calcutta: The Asiatic Society, v.2). The immediate predecessor of the Systematik was a catalog for a newly-acquired collection at the Royal Conservatory of Music in Brussels. The collection included a large number of instruments from India, and the curator, Victor-Charles Mahillon, familiar with the Indian four-part system, decided to apply it in preparing his catalog, published in 1880 (this is best documented by Nazir Jairazbhoy in Selected Reports in Ethnomusicology – see 1990 in the timeline below). -

©Studentsavvy Music Around the World Unit I Thank You For

©studentsavvy Music Around the World Unit I thank you for StudentSavvy © 2016 downloading! Thank you for downloading StudentSavvy’s Music Around the World Unit! If you have any questions regarding this product, please email me at [email protected] Be sure to stay updated and follow for the latest freebies and giveaways! studentsavvyontpt.blogspot.com www.facebook.com/studentsavvy www.pinterest.com/studentsavvy wwww.teacherspayteachers.com/store/studentsavvy clipart by EduClips and IROM BOOK http://www.hm.h555.net/~irom/musical_instruments/ Don’t have a QR Code Reader? That’s okay! Here are the URL links to all the video clips in the unit! Music of Spain: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=_7C8MdtnIHg Music of Japan: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=5OA8HFUNfIk Music of Africa: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=4g19eRur0v0 Music of Italy: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=U3FOjDnNPHw Music of India: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qQ2Yr14Y2e0 Music of Russia: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EEiujug_Zcs Music of France: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Ge46oJju-JE Music of Brazil: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=jQLvGghaDbE ©StudentSavvy2016 Don’t leave out these countries in your music study! Click here to study the music of Mexico, China, the Netherlands, Germany, Australia, USA, Hawaii, and the U.K. You may also enjoy these related resources: Music Around the WorLd Table Of Contents Overview of Musical Instrument Categories…………………6 Music of Japan – Read and Learn……………………………………7 Music of Japan – What I learned – Recall.……………………..8 Explore -

Electrophonic Musical Instruments

G10H CPC COOPERATIVE PATENT CLASSIFICATION G PHYSICS (NOTES omitted) INSTRUMENTS G10 MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS; ACOUSTICS (NOTES omitted) G10H ELECTROPHONIC MUSICAL INSTRUMENTS (electronic circuits in general H03) NOTE This subclass covers musical instruments in which individual notes are constituted as electric oscillations under the control of a performer and the oscillations are converted to sound-vibrations by a loud-speaker or equivalent instrument. WARNING In this subclass non-limiting references (in the sense of paragraph 39 of the Guide to the IPC) may still be displayed in the scheme. 1/00 Details of electrophonic musical instruments 1/053 . during execution only {(voice controlled (keyboards applicable also to other musical instruments G10H 5/005)} instruments G10B, G10C; arrangements for producing 1/0535 . {by switches incorporating a mechanical a reverberation or echo sound G10K 15/08) vibrator, the envelope of the mechanical 1/0008 . {Associated control or indicating means (teaching vibration being used as modulating signal} of music per se G09B 15/00)} 1/055 . by switches with variable impedance 1/0016 . {Means for indicating which keys, frets or strings elements are to be actuated, e.g. using lights or leds} 1/0551 . {using variable capacitors} 1/0025 . {Automatic or semi-automatic music 1/0553 . {using optical or light-responsive means} composition, e.g. producing random music, 1/0555 . {using magnetic or electromagnetic applying rules from music theory or modifying a means} musical piece (automatically producing a series of 1/0556 . {using piezo-electric means} tones G10H 1/26)} 1/0558 . {using variable resistors} 1/0033 . {Recording/reproducing or transmission of 1/057 . by envelope-forming circuits music for electrophonic musical instruments (of 1/0575 . -

ROVA Saxophone Quartet

FOR IMMEDIATE RELEASE Contact: Glenn Siegel, 413-320-1089 [email protected] Pioneer Valley Jazz Shares presents: ROVA Saxophone Quartet Pioneer Valley Jazz Shares continues its 4th season with a performance by ROVA Saxophone Quartet: Larry Ochs, tenor and sopranino sax; Bruce Ackley, soprano and tenor sax; Jon Raskin, baritone, alto and sopranino sax; Steve Adams, alto and sopranino sax on Tuesday, January 26, 2016 at 7:30pm at 121 Club, Eastworks , 116 Pleasant St, Easthampton, MA 01027. Single tickets ($15) available at www.jazzshares.org and at the door. Rova Saxophone Quartet explores the synthesis of composition and collective improvisation, creating exciting, genre-bending music that challenges and inspires. One of the longest-standing groups in the music, Rova has its roots in post-bop, free jazz, avant-rock, and 20th century new music, and draws inspiration from the visual arts and from the traditional and popular music styles of Africa, Asia, Europe and the United States. In noting Rova’s innovative role in developing the all-saxophone ensemble as “a regular and conceptually wide- ranging unit,” The Penguin Guide to Jazz calls its music “a teeming cosmos of saxophone sounds” created by “deliberately eschewing conventional notions about swing [and] prodding at the boundaries of sound and space…” Likewise Jazz: The Rough Guide notes, “Highly inventive, eclectic and willing to experiment, Rova [is] arguably the most exciting of the saxophone quartets to emerge in the format’s late ’70s boom.” Inspired by a broad spectrum of musical influences – from Charles Ives, Edgard Varese, Olivier Messiaen, Iannis Xenakis and Morton Feldman to The Art Ensemble of Chicago, John Coltrane, Anthony Braxton, Steve Lacy, Cecil Taylor, Sun Ra and Ornette Coleman – Rova began in 1978, writing new material, touring, and recording. -

Henry J. Kaiser (1882-1967) by Ray Atkeson, Photographer This Photograph Shows Henry J

Henry J. Kaiser (1882-1967) By Ray Atkeson, Photographer This photograph shows Henry J. Kaiser (back seat left) with Governor Charles Sprague (back seat right) and President Franklin D. Roosevelt (front seat right) during a presidential visit to Kaiser’s Portland Shipyards in 1942. Though he rarely visited Oregon, Henry Kaiser was an influential industrialist whose successful ventures in manufacturing and health care significantly impacted the state. Kaiser was born in Sprout Brook, New York, in 1882, and moved to Spokane, Washington, in 1906. In 1914, with his wife Bess Fosburg Kaiser, he founded the Henry J. Kaiser Company, which specialized in road paving. He expanded his industrial empire over the years and, by the time of Franklin D. Roosevelt's administration in the 1930s, it was one of the “Six Companies" that attracted lucrative federal contracts including those for the Boulder (now Hoover), Bonneville, and Grand Coulee dams. During World War II, Kaiser owned three shipyards in Portland and Vancouver, Washington, through his firm Kaiser Industries. At their peak, these shipyards employed more than 130,000 workers in the Portland area. This photograph shows Henry J. Kaiser (back seat left) with Governor Charles Sprague (back seat right) and President Franklin D. Roosevelt (front seat right) during a presidential visit to Kaiser’s Portland Shipyards in 1942. Labor shortages in the region prompted Kaiser to recruit workers from around the country. Since local officials did not want to build housing for these newcomers, many of whom were African American, in 1942 Kaiser purchased and developed land in the Colombia River floodplain at the far northern edge of Portland. -

Immersion Into Noise

Immersion Into Noise Critical Climate Change Series Editors: Tom Cohen and Claire Colebrook The era of climate change involves the mutation of systems beyond 20th century anthropomorphic models and has stood, until recent- ly, outside representation or address. Understood in a broad and critical sense, climate change concerns material agencies that im- pact on biomass and energy, erased borders and microbial inven- tion, geological and nanographic time, and extinction events. The possibility of extinction has always been a latent figure in textual production and archives; but the current sense of depletion, decay, mutation and exhaustion calls for new modes of address, new styles of publishing and authoring, and new formats and speeds of distri- bution. As the pressures and re-alignments of this re-arrangement occur, so must the critical languages and conceptual templates, po- litical premises and definitions of ‘life.’ There is a particular need to publish in timely fashion experimental monographs that redefine the boundaries of disciplinary fields, rhetorical invasions, the in- terface of conceptual and scientific languages, and geomorphic and geopolitical interventions. Critical Climate Change is oriented, in this general manner, toward the epistemo-political mutations that correspond to the temporalities of terrestrial mutation. Immersion Into Noise Joseph Nechvatal OPEN HUMANITIES PRESS An imprint of MPublishing – University of Michigan Library, Ann Arbor, 2011 First edition published by Open Humanities Press 2011 Freely available online at http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.9618970.0001.001 Copyright © 2011 Joseph Nechvatal This is an open access book, licensed under the Creative Commons By Attribution Share Alike license. Under this license, authors allow anyone to download, reuse, reprint, modify, distribute, and/or copy this book so long as the authors and source are cited and resulting derivative works are licensed under the same or similar license. -

African Drumming in Drum Circles by Robert J

African Drumming in Drum Circles By Robert J. Damm Although there is a clear distinction between African drum ensembles that learn a repertoire of traditional dance rhythms of West Africa and a drum circle that plays primarily freestyle, in-the-moment music, there are times when it might be valuable to share African drumming concepts in a drum circle. In his 2011 Percussive Notes article “Interactive Drumming: Using the power of rhythm to unite and inspire,” Kalani defined drum circles, drum ensembles, and drum classes. Drum circles are “improvisational experiences, aimed at having fun in an inclusive setting. They don’t require of the participants any specific musical knowledge or skills, and the music is co-created in the moment. The main idea is that anyone is free to join and express himself or herself in any way that positively contributes to the music.” By contrast, drum classes are “a means to learn musical skills. The goal is to develop one’s drumming skills in order to enhance one’s enjoyment and appreciation of music. Students often start with classes and then move on to join ensembles, thereby further developing their skills.” Drum ensembles are “often organized around specific musical genres, such as contemporary or folkloric music of a specific culture” (Kalani, p. 72). Robert Damm: It may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music for the sake of enhancing the musical skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience of the participants. PERCUSSIVE NOTES 8 JULY 2017 PERCUSSIVE NOTES 9 JULY 2017 cknowledging these distinctions, it may be beneficial for a drum circle facilitator to introduce elements of African music (culturally specific rhythms, processes, and concepts) for the sake of enhancing the musi- cal skills, cultural knowledge, and social experience Aof the participants in a drum circle. -

Some Notes on John Zorn's Cobra

Some Notes on John Zorn’s Cobra Author(s): JOHN BRACKETT Source: American Music, Vol. 28, No. 1 (Spring 2010), pp. 44-75 Published by: University of Illinois Press Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.5406/americanmusic.28.1.0044 . Accessed: 10/12/2013 15:16 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp . JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of Illinois Press is collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to American Music. http://www.jstor.org This content downloaded from 198.40.30.166 on Tue, 10 Dec 2013 15:16:53 PM All use subject to JSTOR Terms and Conditions JOHN BRACKETT Some Notes on John Zorn’s Cobra The year 2009 marks the twenty-fifth anniversary of John Zorn’s cele- brated game piece for improvisers, Cobra. Without a doubt, Cobra is Zorn’s most popular and well-known composition and one that has enjoyed remarkable success and innumerable performances all over the world since its premiere in late 1984 at the New York City club, Roulette. Some noteworthy performances of Cobra include those played by a group of jazz journalists and critics, an all-women performance, and a hip-hop ver- sion as well!1 At the same time, Cobra is routinely played by students in colleges and universities all over the world, ensuring that the work will continue to grow and evolve in the years to come. -

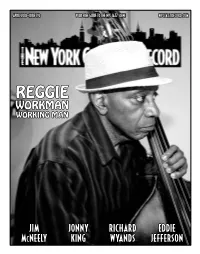

Reggie Workman Working Man

APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 YOUR FREE GUIDE TO THE NYC JAZZ SCENE NYCJAZZRECORD.COM REGGIE WORKMAN WORKING MAN JIM JONNY RICHARD EDDIE McNEELY KING WYANDS JEFFERSON Managing Editor: Laurence Donohue-Greene Editorial Director & Production Manager: Andrey Henkin To Contact: The New York City Jazz Record 66 Mt. Airy Road East APRIL 2018—ISSUE 192 Croton-on-Hudson, NY 10520 United States Phone/Fax: 212-568-9628 New York@Night 4 Laurence Donohue-Greene: Interview : JIM Mcneely 6 by ken dryden [email protected] Andrey Henkin: [email protected] Artist Feature : JONNY KING 7 by donald elfman General Inquiries: [email protected] ON The COver : REGGIE WORKMAN 8 by john pietaro Advertising: [email protected] Encore : RICHARD WYANDS by marilyn lester Calendar: 10 [email protected] VOXNews: Lest WE Forget : EDDIE JEFFERSON 10 by ori dagan [email protected] LAbel Spotlight : MINUS ZERO by george grella US Subscription rates: 12 issues, $40 11 Canada Subscription rates: 12 issues, $45 International Subscription rates: 12 issues, $50 For subscription assistance, send check, cash or vOXNEWS 11 by suzanne lorge money order to the address above or email [email protected] Obituaries by andrey henkin Staff Writers 12 David R. Adler, Clifford Allen, Duck Baker, Stuart Broomer, FESTIvAL REPORT Robert Bush, Thomas Conrad, 13 Ken Dryden, Donald Elfman, Phil Freeman, Kurt Gottschalk, Tom Greenland, Anders Griffen, CD REviews 14 Tyran Grillo, Alex Henderson, Robert Iannapollo, Matthew Kassel, Marilyn Lester, Suzanne -

BULLETIN of the INTERNATIONAL FOLK MUSIC COUNCIL

BULLETIN of the INTERNATIONAL FOLK MUSIC COUNCIL No. XXVIII July, 1966 Including the Report of the EXECUTIVE BOARD for the period July 1, 1964 to June 30, 1965 INTERNATIONAL FOLK MUSIC COUNCIL 21 BEDFORD SQUARE, LONDON, W.C.l ANNOUNCEMENTS CONTENTS APOLOGIES PAGE The Executive Secretary apologizes for the great delay in publi cation of this Bulletin. A nnouncements : The Journal of the IFMC for 1966 has also been delayed in A p o l o g i e s ..............................................................................1 publication, for reasons beyond our control. We are sorry for the Address C h a n g e ....................................................................1 inconvenience this may have caused to our members and subscribers. Executive Board M e e t i n g .................................................1 NEW ADDRESS OF THE IFMC HEADQUARTERS Eighteenth C onference .......................................................... 1 On May 1, 1966, the IFMC moved its headquarters to the building Financial C r i s i s ....................................................................1 of the Royal Anthropological Institute, at 21 Bedford Square, London, W.C.l, England. The telephone number is MUSeum 2980. This is expected to be the permanent address of the Council. R e p o r t o f th e E xecutiv e Board July 1, 1964-Ju n e 30, 1965- 2 EXECUTIVE BOARD MEETING S ta tem ent of A c c o u n t s .....................................................................6 The Executive Board of the IFMC held its thirty-third meeting in Berlin on July 14 to 17, 1965, by invitation of the International Institute for Comparative Music Studies and Documentation, N a tio n a l C ontributions .....................................................................7 directed by M. -

Explore Music 7 World Drumming.Pdf (PDF 2.11

Explore Music 7: World Drumming Explore Music 7: World Drumming (Revised 2020) Page 1 Explore Music 7: World Drumming (Revised 2020) Page 2 Contents Explore Music 7: World Drumming Overview ........................................................................................................................................5 Unit 1: The Roots of Drumming (4-5 hours)..................................................................................7 Unit 2: Drum Circles (8-10 hours) .................................................................................................14 Unit 3: Ensemble Playing (11-14 hours) ........................................................................................32 Supporting Materials.......................................................................................................................50 References.................................................. ....................................................................................69 The instructional hours indicated for each unit provide guidelines for planning, rather than strict requirements. The sequence of skill and concept development is to be the focus of concern. Teachers are encouraged to adapt these suggested timelines to meet the needs of their students. To be effective in teaching this module, it is important to use the material contained in Explore Music: Curriculum Framework and Explore Music: Appendices. Therefore, it is recommended that these two components be frequently referenced to support the suggestions for -

Land- En Volkenkunde

Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Verhandelingen van het Koninklijk Instituut voor Taal- , Land- en Volkenkunde Edited by Rosemarijn Hoefte (kitlv, Leiden) Henk Schulte Nordholt (kitlv, Leiden) Editorial Board Michael Laffan (Princeton University) Adrian Vickers (The University of Sydney) Anna Tsing (University of California Santa Cruz) volume 313 The titles published in this series are listed at brill.com/ vki Music of the Baduy People of Western Java Singing is a Medicine By Wim van Zanten LEIDEN | BOSTON This is an open access title distributed under the terms of the CC BY- NC- ND 4.0 license, which permits any non- commercial use, distribution, and reproduction in any medium, provided no alterations are made and the original author(s) and source are credited. Further information and the complete license text can be found at https:// creativecommons.org/ licenses/ by- nc- nd/ 4.0/ The terms of the CC license apply only to the original material. The use of material from other sources (indicated by a reference) such as diagrams, illustrations, photos and text samples may require further permission from the respective copyright holder. Cover illustration: Front: angklung players in Kadujangkung, Kanékés village, 15 October 1992. Back: players of gongs and xylophone in keromong ensemble at circumcision festivities in Cicakal Leuwi Buleud, Kanékés, 5 July 2016. Translations from Indonesian, Sundanese, Dutch, French and German were made by the author, unless stated otherwise. The Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available online at http://catalog.loc.gov LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2020045251 Typeface for the Latin, Greek, and Cyrillic scripts: “Brill”.