Mark E. Smith, Brexit Britain and the Aesthetics and Politics of the Working Class Weird

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music

Stop Smiling Magazine :: Interviews and Reviews: Film + Music + Books ... http://www.stopsmilingonline.com/story_print.php?id=1097 Downtown Dedication: The Return of Polvo (Touch and Go) Monday, June 23, 2008 By Dan Pearson We could have flown out of Newark, landed in Charlotte, and just hit a barbecue spot in Reidsville, but this was after all the Polvo reunion and it deserved more. We needed to feel as if we were making the descent, notice the disparity in New England and Southern spring, endure interminable DC traffic and feel that we had earned our ribs and slaw. So, I packed the Malibu with I-Roy and U-Roy, stomached $4 gas and my friend Bose and I left from Connecticut in a rainstorm, both of us in fleece. Night one we spent at a Ramada in Fredericksburg, never made it to the battlefield or historic downtown, but instead drove down the divided highway to Allman’s BBQ. I’m wary of food blogs, but the culinary scribes were dead-on: best ribs I have ever had outside Texas, enviable pulled pork and slaw, notable sauce in the squirt bottle — all in an old corner diner with spinning stools. What a foundation, not only for the evening, which consisted of ice cold tap Yuengling and inebriated dancing to Def Leppard in the Ramada lounge, but for the show to come. Just a stateline south, yes, Polvo, the seminal math rock quartet, reunited at their Ground Zero, the Cat’s Cradle in Carrboro. In the morning, it was only better, the slow slalom down Route 40 country roads leaving trails of red clay and another barbecue platter at Short Sugar’s in Danville, Virginia. -

Lush's Final Show @ Manchester Academy

LUSH’S FINAL SHOW @ MANCHESTER ACADEMY larecord.com /photos/2016/11/26/lushs-final-show-manchester-academy November 26th, 2016 | Photos Photos by Todd Nakamine 2016 brought a very successful return for Lush with sold out shows, festival appearances and a new EP Blind Spot. But 2016 also brought the final show the band would play at the Manchester Academy to a somewhat somber crowd. We were soaking in every last note all knowing this was the last show ever (sometimes knowing is worse). Kicking off their high energy set with “De-luxe” and plowing through classic after classic covering their entire career including “Kiss Chase,” “Thoughtforms,” “Etheriel,” “Light From A Dead Star,” “Hypocrite,” “Undertow” plus the new already classic Lush track “Out of Control.” While nothing can replace the late Chris Acland’s subtleties that helped define Lush’s sound, drummer Justin Welsh’s hard and fast style of playing added an extra kick apparent in songs like “Ladykiller,” or as Miki Berenyi said should be renamed “Pussygrabber” in light of U.S.A.’s new president elect, as well as “Sweetness and Light.” Acland’s close friend Michael Conroy of Modern English filled in on bass as Phil King left the band in October. Finishing with the final song of the night “Monochrome,” Emma Anderson, Berenyi and Welsh gave their last waves, left the stage for the final time and the crowd quietly shuffled out having been treated with a very special goodbye. Kicking off the night was Brix & The Extricated featuring post punk legends Brix Smith, Steve Hanley and Paul Hanley (The Fall). -

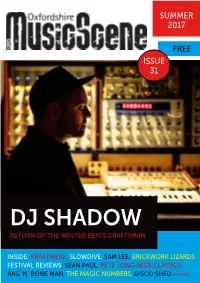

Dj Shadow Return of the Master Beats Craftsman

SUMMER 2017 FREE ISSUE 31 DJ SHADOW RETURN OF THE MASTER BEATS CRAFTSMAN INSIDE: KRAFTWERK, SLOWDIVE, SAM LEE, BRICKWORK LIZARDS FESTIVAL REVIEWS: SEAN PAUL, PETE TONG IBIZA CLASSICS, RAG ‘N’ BONE MAN, THE MAGIC NUMBERS, DISCO SHED & MORE OMS31 MUSIC NEWS There’s a history of multi – venue metro festivals in Cowley Road with Truck’s OX4 and then Gathering setting the pace. Well now Future Perfect have taken up the baton with Ritual Union on Saturday October 21. Venues are the O2 Academy 1 and 2, The Library, The Bullingdon and Truck Store. The first stage of acts announced includes Peace, Toy, Pinkshinyultrablast, Flamingods, Low Island, Dead Reborn local heroes Ride are sounding in fine stage Pretties, Her’s, August List and Candy Says with DJ fettle judging by their appearance at the 6 Music sets from the Drowned in Sound team. Tickets are Festival in Glasgow. The former Creation shoegaze £25 in advance. trailblazers play the New Theatre, Oxford on July 10, having already appeared at Glastonbury, their The Jericho Tavern in Walton Street have a new first local show in many years. They have also promoter to run their upstairs gigs. Heavy Pop announced a major UK tour. The eagerly awaited are well – known in Reading having run the Are new album, the Erol Alkan produced Weather Diaries You Listening? festival there for 5 years. Already is just released. (See our album review in the Local confirmed are an appearance from Tom Williams Releases section). Tickets for New Theatre gig with (formerly of The Boat) on September 16 and Original Spectres supporting, can be bought from Rabbit Foot Spasm Band on October 13 with atgtickets.com Peerless Pirates and Other Dramas. -

The Quietus | Features | a Quietus Interview | We Only Have This Excerp

The Quietus | Features | A Quietus Interview | We Only Have This Excerp... http://thequietus.com/articles/07465-mark-e-smith-interview-the-fall News Reviews Features Opinion Film About Us We Only Have This Excerpt: Mark E Smith Of The Fall Interviewed Kevin E.G. Perry , November 24th, 2011 09:29 Mark E Smith has a drink with Kevin EG Perry and tells him about literary influences and Ersatz GB. Photograph by Valerio Berdini Add your comment » 1 of 21 1/4/2012 10:26 AM The Quietus | Features | A Quietus Interview | We Only Have This Excerp... http://thequietus.com/articles/07465-mark-e-smith-interview-the-fall Like Send 544 people like this. “It’s a shopper’s paradise, isn’t it?” says Mark E Smith as he surveys ‘Smoak’, the inexplicably Texan-themed bar in Manchester’s Malmaison hotel. It’s a Saturday afternoon a month or so before Christmas, and both the hotel bar and the adjacent lobby are crawling with families laden with expensive-looking carrier bags. We collect our beers, chosen at random from a long list of imports, and Smith spots a quiet corner on the other side of the lobby: “We’ll go over there.” He moves in a shuffling gait, and already seems older than his 54 years, but his wit and his work rate haven’t slowed. In the 35 years since he and a handful of mates formed The Fall in an apartment in Prestwich he has released 29 albums under that name. Although his bandmates have long since become the subject of regular rotation, over the years Smith has crafted for himself a complex, literate authorial voice which is as unmistakable as his own Salford anti-vocals. -

NEW RELEASE Cds 24/5/19

NEW RELEASE CDs 24/5/19 BLACK MOUNTAIN Destroyer [Jagjaguwar] £9.99 CATE LE BON Reward [Mexican Summer] £9.99 EARTH Full Upon Her Burning Lips £10.99 FLYING LOTUS Flamagra [Warp] £9.99 HAYDEN THORPE (ex-Wild Beasts) Diviner [Domino] £9.99 HONEYBLOOD In Plain Sight [Marathon] £9.99 MAVIS STAPLES We Get By [ANTI-] £10.99 PRIMAL SCREAM Maximum Rock 'N' Roll: The Singles [2CD] £12.99 SEBADOH Act Surprised £10.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Cooking Vinyl] £9.99 THE WATERBOYS Where The Action Is [Deluxe 2CD w/ Alternative Mixes on Cooking Vinyl] £12.99 AKA TRIO (Feat. Seckou Keita!) Joy £9.99 AMYL & THE SNIFFERS Amyl & The Sniffers [Rough Trade] £9.99 ANDREYA TRIANA Life In Colour £9.99 DADDY LONG LEGS Lowdown Ways [Yep Roc] £9.99 FIRE! ORCHESTRA Arrival £11.99 FLESHGOD APOCALYPSE Veleno [Ltd. CD + Blu-Ray on Nuclear Blast] £14.99 FU MANCHU Godzilla's / Eatin' Dust +4 £11.99 GIA MARGARET There's Always Glimmer £9.99 JOAN AS POLICE WOMAN Joanthology [3CD on PIAS] £11.99 JUSTIN TOWNES EARLE The Saint Of Lost Causes [New West] £9.99 LEE MOSES How Much Longer Must I Wait? Singles & Rarities 1965-1972 [Future Days] £14.99 MALCOLM MIDDLETON (ex-Arab Strap) Bananas [Triassic Tusk] £9.99 PETROL GIRLS Cut & Stitch [Hassle] £9.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Deluxe CD w/ Bonus Tracks + More on Mascot]£14.99 STRAY CATS 40 [Mascot] £11.99 THE DAMNED THINGS High Crimes [Nuclear Blast] FEAT MEMBERS OF ANTHRAX, FALL OUT BOY, ALKALINE TRIO & EVERY TIME I DIE! £10.99 THE GET UP KIDS Problems [Big Scary Monsters] £9.99 THE MYSTERY LIGHTS Too Much Tension! [Wick] £10.99 COMPILATIONS VARIOUS ARTISTS Lux And Ivys Good For Nothin' Tunes [2CD] £11.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Max's Skansas City £9.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS Par Les Damné.E.S De La Terre (By The Wretched Of The Earth) £13.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The Hip Walk - Jazz Undercurrents In 60s New York [BGP] £10.99 VARIOUS ARTISTS The World Needs Changing: Street Funk.. -

The Fall Free Download

THE FALL FREE DOWNLOAD Albert Camus | 160 pages | 07 May 1991 | Random House USA Inc | 9780679720225 | English | New York, United States About Tomatometer Daisy Drake 7 episodes, Otto Andrew Roussouw When it becomes apparent that a serial killer is on the loose, local detectives must work with Stella to find and capture Paul The Fall, who is attacking young professional women in the city of Belfast. Allan Cubitt. Wikimedia Commons has media related to The Fall band. All the cars in the shots on location at the hospital have steering wheels on the right The Fall of the car, revealing that they are not actually in LA. Error: please try again. Retrieved 2 The Fall Spin : Download as PDF Printable version. Retrieved 26 October Spector talks to Kiera about out-of-body experiences and moves to a psych ward. Brix's tenure in the group marked a shift towards the relatively conventional, with the songs she co-wrote often having strong pop hooks and more orthodox verse-chorus-verse structures. The Con. Perfect for a binge watch and a good chat afterwards. The Vast Abyss. Black Mirror: Season 5. The Quietus. Darkness Visible. Middles, Mick; Smith, Mark E. Real Quick. Smith dead: Eight of The Fall's best tracks ". Get some streaming picks. Watch all you want. Katie enraged at the media treatment of him, decides to take matters into her own hands. Series Info. Retrieved 26 August How did you buy your ticket? Liam Spector 10 episodes, Log in here. The Haunting of Bly Manor. The Belfast Telegraph. Television Without Pity. -

Brand New Cd & Dvd Releases 2006 6,400 Titles

BRAND NEW CD & DVD RELEASES 2006 6,400 TITLES COB RECORDS, PORTHMADOG, GWYNEDD,WALES, U.K. LL49 9NA Tel. 01766 512170: Fax. 01766 513185: www. cobrecords.com // e-mail [email protected] CDs, DVDs Supplied World-Wide At Discount Prices – Exports Tax Free SYMBOLS USED - IMP = Imports. r/m = remastered. + = extra tracks. D/Dble = Double CD. *** = previously listed at a higher price, now reduced Please read this listing in conjunction with our “ CDs AT SPECIAL PRICES” feature as some of the more mainstream titles may be available at cheaper prices in that listing. Please note that all items listed on this 2006 6,400 titles listing are all of U.K. manufacture (apart from Imports which are denoted IM or IMP). Titles listed on our list of SPECIALS are a mix of U.K. and E.C. manufactured product. We will supply you with whichever item for the price/country of manufacture you choose to order. ************************************************************************************************************* (We Thank You For Using Stock Numbers Quoted On Left) 337 AFTER HOURS/G.DULLI ballads for little hyenas X5 11.60 239 ANATA conductor’s departure B5 12.00 327 AFTER THE FIRE a t f 2 B4 11.50 232 ANATHEMA a fine day to exit B4 11.50 ST Price Price 304 AG get dirty radio B5 12.00 272 ANDERSON, IAN collection Double X1 13.70 NO Code £. 215 AGAINST ALL AUTHOR restoration of chaos B5 12.00 347 ANDERSON, JON animatioin X2 12.80 92 ? & THE MYSTERIANS best of P8 8.30 305 AGALAH you already know B5 12.00 274 ANDERSON, JON tour of the universe DVD B7 13.00 -

Every Purchase Includes a Free Hot Drink out of Stock, but Can Re-Order New Arrival / Re-Stock

every purchase includes a free hot drink out of stock, but can re-order new arrival / re-stock VINYL PRICE 1975 - 1975 £ 22.00 30 Seconds to Mars - America £ 15.00 ABBA - Gold (2 LP) £ 23.00 ABBA - Live At Wembley Arena (3 LP) £ 38.00 Abbey Road (50th Anniversary) £ 27.00 AC/DC - Live '92 (2 LP) £ 25.00 AC/DC - Live At Old Waldorf In San Francisco September 3 1977 (Red Vinyl) £ 17.00 AC/DC - Live In Cleveland August 22 1977 (Orange Vinyl) £ 20.00 AC/DC- The Many Faces Of (2 LP) £ 20.00 Adele - 21 £ 19.00 Aerosmith- Done With Mirrors £ 25.00 Air- Moon Safari £ 26.00 Al Green - Let's Stay Together £ 20.00 Alanis Morissette - Jagged Little Pill £ 17.00 Alice Cooper - The Many Faces Of Alice Cooper (Opaque Splatter Marble Vinyl) (2 LP) £ 21.00 Alice in Chains - Live at the Palladium, Hollywood £ 17.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Enlightened Rogues £ 16.00 ALLMAN BROTHERS BAND - Win Lose Or Draw £ 16.00 Altered Images- Greatest Hits £ 20.00 Amy Winehouse - Back to Black £ 20.00 Andrew W.K. - You're Not Alone (2 LP) £ 20.00 ANTAL DORATI - LONDON SYMPHONY ORCHESTRA - Stravinsky-The Firebird £ 18.00 Antonio Carlos Jobim - Wave (LP + CD) £ 21.00 Arcade Fire - Everything Now (Danish) £ 18.00 Arcade Fire - Funeral £ 20.00 ARCADE FIRE - Neon Bible £ 23.00 Arctic Monkeys - AM £ 24.00 Arctic Monkeys - Tranquility Base Hotel + Casino £ 23.00 Aretha Franklin - The Electrifying £ 10.00 Aretha Franklin - The Tender £ 15.00 Asher Roth- Asleep In The Bread Aisle - Translucent Gold Vinyl £ 17.00 B.B. -

Nine Constructions of the Crossover Between Western Art and Popular Musics (1995-2005)

Subject to Change: Nine constructions of the crossover between Western art and popular musics (1995-2005) Aliese Millington Thesis submitted to fulfil the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy ~ Elder Conservatorium of Music Faculty of Humanities and Social Sciences The University of Adelaide October 2007 Contents List of Tables…..…………………………………………………………....iii List of Plates…………………………………………………………….......iv Abstract……………………………………………………………………...v Declaration………………………………………………………………….vi Acknowledgements………………………………………………………...vii Chapter One Introduction…………………………………..…..1 Chapter Two Crossover as a marketing strategy…………....…43 Chapter Three Crossover: constructing individuality?.................69 Chapter Four Shortcuts and signposts: crossover and media themes..…………………...90 Chapter Five Evoking associations: crossover, prestige and credibility………….….110 Chapter Six Attracting audiences: alternate constructions of crossover……..……..135 Chapter Seven Death and homogenization: crossover and two musical debates……..……...160 Chapter Eight Conclusions…………………..………………...180 Appendices Appendix A The historical context of crossover ….………...186 Appendix B Biographies of the four primary artists..…….....198 References …...……...………………………………………………...…..223 ii List of Tables Table 1 Nine constructions of crossover…………………………...16-17 iii List of Plates 1 Promotional photograph of bond reproduced from (Shine 2002)……………………………………….19 2 Promotional photograph of FourPlay String Quartet reproduced from (FourPlay 2007g)………………………………….20 3 Promotional -

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989

The History of Rock Music: 1976-1989 New Wave, Punk-rock, Hardcore History of Rock Music | 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-75 | 1976-89 | The early 1990s | The late 1990s | The 2000s | Alpha index Musicians of 1955-66 | 1967-69 | 1970-76 | 1977-89 | 1990s in the US | 1990s outside the US | 2000s Back to the main Music page (Copyright © 2009 Piero Scaruffi) Punk-rock (These are excerpts from my book "A History of Rock and Dance Music") London's burning TM, ®, Copyright © 2005 Piero Scaruffi All rights reserved. The effervescence of New York's underground scene was contagious and spread to England with a 1976 tour of the Ramones that was artfully manipulated to start a fad (after the "100 Club Festival" of september 1976 that turned British punk-rock into a national phenomenon). In the USA the punk subculture was a combination of subterranean record industry and of teenage angst. In Britain it became a combination of fashion and of unemployment. Music in London had been a component of fashion since the times of the Swinging London (read: Rolling Stones). Punk-rock was first and foremost a fad that took over the Kingdom by storm. However, the social component was even stronger than in the USA: it was not only a generic malaise, it was a specific catastrophe. The iron rule of prime minister Margaret Thatcher had salvaged Britain from sliding into the Third World, but had caused devastation in the social fabric of the industrial cities, where unemployment and poverty reached unprecedented levels and racial tensions were brooding. -

Record Dreams Catalog

RECORD DREAMS 50 Hallucinations and Visions of Rare and Strange Vinyl Vinyl, to: vb. A neologism that describes the process of immersing yourself in an antique playback format, often to the point of obsession - i.e. I’m going to vinyl at Utrecht, I may be gone a long time. Or: I vinyled so hard that my bank balance has gone up the wazoo. The end result of vinyling is a record collection, which is defned as a bad idea (hoarding, duplicating, upgrading) often turned into a good idea (a saleable archive). If you’re reading this, you’ve gone down the rabbit hole like the rest of us. What is record collecting? Is it a doomed yet psychologically powerful wish to recapture that frst thrill of adolescent recognition or is it a quite understandable impulse to preserve and enjoy totemic artefacts from the frst - perhaps the only - great age of a truly mass art form, a mass youth culture? Fingering a particularly juicy 45 by the Stooges, Sweet or Sylvester, you could be forgiven for answering: fuck it, let’s boogie! But, you know, you’re here and so are we so, to quote Double Dee and Steinski, what does it all mean? Are you looking for - to take a few possibles - Kate Bush picture discs, early 80s Japanese synth on the Vanity label, European Led Zeppelin 45’s (because of course they did not deign to release singles in the UK), or vastly overpriced and not so good druggy LPs from the psychedelic fatso’s stall (Rainbow Ffolly, we salute you)? Or are you just drifting, browsing, going where the mood and the vinyl takes you? That’s where Utrecht scores. -

Modulator Für Stuttgart September & Oktober 0910|15 D As Programmheft

FREIES RADIO Modulator FÜR STUTTGART September & Oktober 0910|15 D as Programmheft Der NSU- Untersuchungs- ausschuss Baden- Württemberg Ein Zwischenbericht ThemaAnzeigen Editorial Geneigte Hörerinnen und Hörer, Inhalt wir freuen uns, Ihnen wieder ein höchst abwechslungsreiches Programm anbieten zu können. 3 Editorial Die Redakteurin Janka Kluge versucht in ihrem Bericht 4 Vorstands Stimme Licht ins Dunkel des baden-württembergischen NSU- Die Neuen sind die alten Untersuchungsausschusses zu bringen. Der Fall um die Ermordung der Polizistin Michelle Kiesewetter wird trotz aller 5 Thema Aufklärungsbeteuerungen zunehmend mysteriöser. Der NSU-Untersuchungsausschuss Baden-Württemberg Erfreulicheres ist aber auch zu melden. 10 Programm September 2015 So findet zum Beispiel am 26. September das traditio- nelle Sommerfest des Freien Radios für Stuttgart im Hof der 20 Programm Oktober 2015 Stöckachstraße 16a statt. Geplant sind unter anderem span- 30 Termine nende Live-Acts und Open-Air Radio - dazu Leckeres vom Grill 30 Impressum und Getränke. Freies Radio für Stuttgart Die Kabarettsendung »Vorsicht bissiger Mund!« feiert bereits 31 Index www.freies-radio.de zehnjähriges Jubiläum und das mit einer Livesendung im Rahmen von radioSCHAUen. Am 6. Oktober treten Eugen Butzlab, Erna T-Shirts, Taschen und mehr. Hämmerle und der Prediger Salomo gemeinsam auf. Dazu gibt Mit FRS-Motiven. es einen heftigen Schlagabtausch zwischen Franz Josef Strauß 1033660.spreadshirt.de und Herbert Wehner wegen Stuttgart 21 bei dieser Ausgabe der »Lästerwelle«. 047 Die »Nachmittage am Pool« bringen Tondokumente vom Bitte per Post an: Freies Radio für Stuttgart, Stöckachstr. 16a, 70190 Stuttgart Stammheim-Prozess. Zu Wort kommen unter anderem Gudrun Ich möchte das Freie Radio für Stuttgart unterstützen und werde Mitglied im Förderverein: Ensslin, Ulrike Meinhof, Andreas Baader und Jan-Carl Raspe.