Polygynandry and Sexual Size Dimorphism in The

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Mechanoreceptors in Early Developmental Stages of the Pycnogonida

UACE2019 - Conference Proceedings Mechanoreceptors in Early Developmental Stages of the Pycnogonida John A. Fornshell * a a U.S. National Museum of Natural History Department of Invertebrate Zoology Smithsonian Institution Washington, D.C. USA *Correspondence: [email protected]; Tel. (571) 426-2398 ABSTRACT Members of the phylum Arthropoda detect fluid flow and sound/particle vibrations using sensory organs called sensilla. These sensilla detect sound/particle vibrations in the boundary layer. In the present study, archived specimens from the United States National Museum of Natural History were examined in an effort to extend our knowledge of the presence of sensilla on the early post hatching developmental stages, first and second instars, of pycnogonids. In the work presented here we look at three families, four genera and ten species of early post hatching developmental stages of sea spiders. They are Family Ammotheidae, Achelia cuneatis Child, 1999, Ammothea allopodes Fry and Hedgpeth, 1969, Ammothea carolinensis Leach 1814, Ammothea clausi Pfeffer, 1889, Ammothea striata (Möbius, 1902), Family Nymphonidae, Nymphon grossipes (Fabricius, 1780), N. australe Hodgson, 1902, N. charcoti Bouvier, 1911, N. Tenellum (Sars, 1888) and Pycnogonidae, Pentapycnon charcoti Bouvier, 1910. Electron micrograph images of these species were used to identify and describe the sensilla present. Most body organs such as mouthparts, the eye tubercle, appendages and spines are proportionally much smaller in the early post hatching developmental stages compared to their size in the adults, while the sensilla are comparable in size and shape to those found on the adults. In the first instar of Pentapycnon charcoti sensilla are present, but not in the adult. -

A Polyandrous Society in Transition: a CASE STUDY of JAUNSAR-BAWAR

10/31/2014 A Polyandrous Society in transition: A CASE STUDY OF JAUNSAR-BAWAR SUBMITTED BY: Nargis Jahan IndraniTalukdar ShrutiChoudhary (Department of Sociology) (Delhi School of Economics) Abstract Man being a social animal cannot survive alone and has therefore been livingin groups or communities called families for ages. How these ‘families’ come about through the institution of marriage or any other way is rather an elaborate and an arduous notion. India along with its diverse people and societies offers innumerable ways by which people unite to come together as a family. Polyandry is one such way that has been prevalent in various regions of the sub-continent evidently among the Paharis of Himachal Pradesh, the Todas of Nilgiris, Nairs of Travancore and the Ezhavas of Malabar. While polyandrous unions have disappeared from the traditions of many of the groups and tribes, it is still practiced by some Jaunsaris—an ethnic group living in the lower Himalayan range—especially in the JaunsarBawar region of Uttarakhand.The concept of polyandry is so vast and mystifying that people who have just heard of the practice or the people who even did an in- depth study of it are confused in certain matters regarding it. This thesis aims at providing answers to many questions arising in the minds of people who have little or no knowledge of this subject. In this paper we have tried to find out why people follow this tradition and whether or not it has undergone transition. Also its various characteristics along with its socio-economic issues like the state and position of women in such a society and how the economic balance in a polyandrous family is maintained has been looked into. -

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee

Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories Compiled by S. Oldfield Edited by D. Procter and L.V. Fleming ISBN: 1 86107 502 2 © Copyright Joint Nature Conservation Committee 1999 Illustrations and layout by Barry Larking Cover design Tracey Weeks Printed by CLE Citation. Procter, D., & Fleming, L.V., eds. 1999. Biodiversity: the UK Overseas Territories. Peterborough, Joint Nature Conservation Committee. Disclaimer: reference to legislation and convention texts in this document are correct to the best of our knowledge but must not be taken to infer definitive legal obligation. Cover photographs Front cover: Top right: Southern rockhopper penguin Eudyptes chrysocome chrysocome (Richard White/JNCC). The world’s largest concentrations of southern rockhopper penguin are found on the Falkland Islands. Centre left: Down Rope, Pitcairn Island, South Pacific (Deborah Procter/JNCC). The introduced rat population of Pitcairn Island has successfully been eradicated in a programme funded by the UK Government. Centre right: Male Anegada rock iguana Cyclura pinguis (Glen Gerber/FFI). The Anegada rock iguana has been the subject of a successful breeding and re-introduction programme funded by FCO and FFI in collaboration with the National Parks Trust of the British Virgin Islands. Back cover: Black-browed albatross Diomedea melanophris (Richard White/JNCC). Of the global breeding population of black-browed albatross, 80 % is found on the Falkland Islands and 10% on South Georgia. Background image on front and back cover: Shoal of fish (Charles Sheppard/Warwick -

Phylogenomic Resolution of Sea Spider Diversification Through Integration Of

bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929612; this version posted February 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. All rights reserved. No reuse allowed without permission. Phylogenomic resolution of sea spider diversification through integration of multiple data classes 1Jesús A. Ballesteros†, 1Emily V.W. Setton†, 1Carlos E. Santibáñez López†, 2Claudia P. Arango, 3Georg Brenneis, 4Saskia Brix, 5Esperanza Cano-Sánchez, 6Merai Dandouch, 6Geoffrey F. Dilly, 7Marc P. Eleaume, 1Guilherme Gainett, 8Cyril Gallut, 6Sean McAtee, 6Lauren McIntyre, 9Amy L. Moran, 6Randy Moran, 5Pablo J. López-González, 10Gerhard Scholtz, 6Clay Williamson, 11H. Arthur Woods, 12Ward C. Wheeler, 1Prashant P. Sharma* 1 Department of Integrative Biology, University of Wisconsin–Madison, Madison, WI, USA 2 Queensland Museum, Biodiversity Program, Brisbane, Australia 3 Zoologisches Institut und Museum, Cytologie und Evolutionsbiologie, Universität Greifswald, Greifswald, Germany 4 Senckenberg am Meer, German Centre for Marine Biodiversity Research (DZMB), c/o Biocenter Grindel (CeNak), Martin-Luther-King-Platz 3, Hamburg, Germany 5 Biodiversidad y Ecología Acuática, Departamento de Zoología, Facultad de Biología, Universidad de Sevilla, Sevilla, Spain 6 Department of Biology, California State University-Channel Islands, Camarillo, CA, USA 7 Départment Milieux et Peuplements Aquatiques, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, Paris, France 8 Institut de Systématique, Emvolution, Biodiversité (ISYEB), Sorbonne Université, CNRS, Concarneau, France 9 Department of Biology, University of Hawai’i at Mānoa, Honolulu, HI, USA Page 1 of 31 bioRxiv preprint doi: https://doi.org/10.1101/2020.01.31.929612; this version posted February 2, 2020. The copyright holder for this preprint (which was not certified by peer review) is the author/funder. -

Evolution of Pycnogonid Life History Traits Eric Carl Lovely University of New Hampshire, Durham

University of New Hampshire University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository Doctoral Dissertations Student Scholarship Winter 1999 Evolution of pycnogonid life history traits Eric Carl Lovely University of New Hampshire, Durham Follow this and additional works at: https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation Recommended Citation Lovely, Eric Carl, "Evolution of pycnogonid life history traits" (1999). Doctoral Dissertations. 1975. https://scholars.unh.edu/dissertation/1975 This Dissertation is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Scholarship at University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. It has been accepted for inclusion in Doctoral Dissertations by an authorized administrator of University of New Hampshire Scholars' Repository. For more information, please contact [email protected]. INFORMATION TO USERS This manuscript has been reproduced from the microfilm master. UMI films the text directly from the original or copy submitted. Thus, some thesis and dissertation copies are in typewriter face, while others may be from any type of computer printer. The quality of this reproduction is dependent upon the quality of the copy submitted. Broken or indistinct print, colored or poor quality illustrations and photographs, print bleedthrough, substandard margins, and improper alignment can adversely affect reproduction. In the unlikely event that the author did not send UMI a complete manuscript and there are missing pages, these will be noted. Also, if unauthorized copyright material had to be removed, a note will indicate the deletion. Oversize materials (e.g., maps, drawings, charts) are reproduced by sectioning the original, beginning at the upper left-hand comer and continuing from left to right in equal sections with small overlaps. -

Polygynandry, Extra-Group Paternity and Multiple-Paternity Litters In

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 5294–5306 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03571.x Polygynandry,Blackwell Publishing Ltd extra-group paternity and multiple-paternity litters in European badger (Meles meles) social groups HANNAH L. DUGDALE,*† DAVID W. MACDONALD,* LISA C. POPE† and TERRY BURKE† *Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Tubney House, Abingdon Road, Tubney OX13 5QL, UK, †Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Western Bank, Sheffield S10 2TN, UK Abstract The costs and benefits of natal philopatry are central to the formation and maintenance of social groups. Badger groups, thought to form passively according to the resource dispersion hypothesis (RDH), are maintained through natal philopatry and delayed dispersal; however, there is minimal evidence for the functional benefits of such grouping. We assigned parentage to 630 badger cubs from a high-density population in Wytham Woods, Oxford, born between 1988 and 2005. Our methodological approach was different to previous studies; we used 22 microsatellite loci to assign parent pairs, which in combination with sibship inference provided a high parentage assignment rate. We assigned both parents to 331 cubs at ≥ 95% confidence, revealing a polygynandrous mating system with up to five mothers and five fathers within a social group. We estimated that only 27% of adult males and 31% of adult females bred each year, suggesting a cost to group living for both sexes. Any strong motivation or selection to disperse, however, may be reduced because just under half of the paternities were gained by extra-group males, mainly from neighbouring groups, with males displaying a mixture of paternity strategies. -

Arthropoda: Pycnogonida)

European Journal of Taxonomy 286: 1–33 ISSN 2118-9773 http://dx.doi.org/10.5852/ejt.2017.286 www.europeanjournaloftaxonomy.eu 2017 · Sabroux R. et al. This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 3.0 License. DNA Library of Life, research article urn:lsid:zoobank.org:pub:8B9DADD0-415E-4120-A10E-8A3411C1C1A4 Biodiversity and phylogeny of Ammotheidae (Arthropoda: Pycnogonida) Romain SABROUX 1, Laure CORBARI 2, Franz KRAPP 3, Céline BONILLO 4, Stépahnie LE PRIEUR 5 & Alexandre HASSANIN 6,* 1,2,6 UMR 7205, Institut de Systématique, Evolution et Biodiversité, Département Systématique et Evolution, Sorbonne Universités, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, 55 rue Buffon, CP 51, 75005 Paris, France. 3 Zoologisches Forschungsmuseum Alexander Koenig, Adenauerallee 160, 53113 Bonn, Germany. 4,5 UMS CNRS 2700, Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle, CP 26, 57 rue Cuvier, 75231 Paris Cedex 05, France. * Corresponding author: [email protected] 1 Email: [email protected] 2 Email: [email protected] 3 Email: [email protected] 4 Email: [email protected] 5 Email: [email protected] 1 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:F48B4ABE-06BD-41B1-B856-A12BE97F9653 2 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:9E5EBA7B-C2F2-4F30-9FD5-1A0E49924F13 3 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:331AD231-A810-42F9-AF8A-DDC319AA351A 4 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:7333D242-0714-41D7-B2DB-6804F8064B13 5 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:5C9F4E71-9D73-459F-BABA-7495853B1981 6 urn:lsid:zoobank.org:author:0DCC3E08-B2BA-4A2C-ADA5-1A256F24DAA1 Abstract. The family Ammotheidae is the most diversified group of the class Pycnogonida, with 297 species described in 20 genera. -

Mate Choice | Principles of Biology from Nature Education

contents Principles of Biology 171 Mate Choice Reproduction underlies many animal behaviors. The greater sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus). Female sage grouse evaluate males as sexual partners on the basis of the feather ornaments and the males' elaborate displays. Stephen J. Krasemann/Science Source. Topics Covered in this Module Mating as a Risky Behavior Major Objectives of this Module Describe factors associated with specific patterns of mating and life history strategies of specific mating patterns. Describe how genetics contributes to behavioral phenotypes such as mating. Describe the selection factors influencing behaviors like mate choice. page 882 of 989 3 pages left in this module contents Principles of Biology 171 Mate Choice Mating as a Risky Behavior Different species have different mating patterns. Different species have evolved a range of mating behaviors that vary in the number of individuals involved and the length of time over which their relationships last. The most open type of relationship is promiscuity, in which all members of a community can mate with each other. Within a promiscuous species, an animal of either gender may mate with any other male or female. No permanent relationships develop between mates, and offspring cannot be certain of the identity of their fathers. Promiscuous behavior is common in bonobos (Pan paniscus), as well as their close relatives, the chimpanzee (P. troglodytes). Bonobos also engage in sexual activity for activities other than reproduction: to greet other members of the community, to release social tensions, and to resolve conflicts. Test Yourself How might promiscuous behavior provide an evolutionary advantage for males? Submit Some animals demonstrate polygamous relationships, in which a single individual of one gender mates with multiple individuals of the opposite gender. -

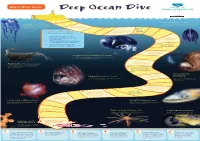

Deep Ocean Dive

Start Dive Here DDeepeep OceanOcean DiveDive UNIVERSITY OF OTAGO Photos Courtesy of 1 Comb Jelly (Pleurobrachia sp.) 2 Comb jellies take their name from the bands of cilia or combs that (Physalia physalis) beat in waves, shimmering all colours of the rainbow and propelling Bluebottle the animal forward. Bluebottle jellyfish, an oceanic creature, is often found 3 Problems with submarine. washed ashore on New Zealand’s exposed beaches, Miss a turn while it is fixed. following stormy weather. The deep ocean is a similar You see a lot of new deep-sea temperature to 4 creatures. Miss a turn while you your fridge, photograph them. ~3 C Object of the Game 7 To find the elusive Colossal Squid! 5 8 6 9 Take turns throwing the die and 1. moving your submarine forward. Follow the instructions on the square Something swimming where you land. past the window. 10 Follow it and move When approaching the bottom, you may 4 spaces. 2. only move if you have the exact number or less required to reach the squid. 3. Once you have found the squid, 11 80-90% of midwater throw the die one more time to discover deep sea animals can your fate as a Deep Sea Explorer! make their own light. 12 13 You forgot to go to the toilet before you left. You must now use the bottle. Googly Eyed Squid (Teuthowenia pellucida) 14 This transparent squid is probably the most common of the small oceanic squid found in New Zealand waters but is rarely seen alive. 15 Low oxygen levels! Speed up to save air. -

Segmentation and Tagmosis in Chelicerata

Arthropod Structure & Development 46 (2017) 395e418 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Arthropod Structure & Development journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/asd Segmentation and tagmosis in Chelicerata * Jason A. Dunlop a, , James C. Lamsdell b a Museum für Naturkunde, Leibniz Institute for Evolution and Biodiversity Science, Invalidenstrasse 43, D-10115 Berlin, Germany b American Museum of Natural History, Division of Paleontology, Central Park West at 79th St, New York, NY 10024, USA article info abstract Article history: Patterns of segmentation and tagmosis are reviewed for Chelicerata. Depending on the outgroup, che- Received 4 April 2016 licerate origins are either among taxa with an anterior tagma of six somites, or taxa in which the ap- Accepted 18 May 2016 pendages of somite I became increasingly raptorial. All Chelicerata have appendage I as a chelate or Available online 21 June 2016 clasp-knife chelicera. The basic trend has obviously been to consolidate food-gathering and walking limbs as a prosoma and respiratory appendages on the opisthosoma. However, the boundary of the Keywords: prosoma is debatable in that some taxa have functionally incorporated somite VII and/or its appendages Arthropoda into the prosoma. Euchelicerata can be defined on having plate-like opisthosomal appendages, further Chelicerata fi Tagmosis modi ed within Arachnida. Total somite counts for Chelicerata range from a maximum of nineteen in Prosoma groups like Scorpiones and the extinct Eurypterida down to seven in modern Pycnogonida. Mites may Opisthosoma also show reduced somite counts, but reconstructing segmentation in these animals remains chal- lenging. Several innovations relating to tagmosis or the appendages borne on particular somites are summarised here as putative apomorphies of individual higher taxa. -

Priorities for Syngnathid Research

TECHNICAL REPORT SERIES No. 10 PRIORITIES FOR SYNGNATHID RESEARCH Keith Martin-Smith Version 1.0. February 2006 Suggested reference Martin-Smith, K. (2006). Priorities For Syngnathid Research. Project Seahorse Technical Report No.10, Version 1.0. Project Seahorse, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia. 10 pp. Online dissemination This document is available online at www.projectseahorse.org (click on Technical Reports link). Note on revision This document was revised and reprinted/reposted in March 2006. Previous copies of the report should be destroyed as this revision replaces the earlier version. Obtaining additional copies Additional copies of this document are available from Project Seahorse, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia, 2202 Main Mall, Vancouver, B.C. V6T 1Z4 Copyright law Although contents of this document have not been copyrighted and may be reprinted entirely, reference to source is appreciated. Published by Project Seahorse, Fisheries Centre, University of British Columbia Series Editor – Keith Martin-Smith i Table of Contents 1. Introduction.......................................................................................................... 1 2. Summary of Priorities for Syngnathid Research.................................................... 1 3. Priority Life-History Parameters for Syngnathids.................................................. 3 4. References............................................................................................................ 7 ii PROJECT SEAHORSE TECHNICAL -

Multiple Mating and Its Relationship to Alternative Modes of Gestation in Male-Pregnant Versus Female-Pregnant fish Species

Multiple mating and its relationship to alternative modes of gestation in male-pregnant versus female-pregnant fish species John C. Avise1 and Jin-Xian Liu Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697 Contributed by John C. Avise, September 28, 2010 (sent for review August 20, 2010) We construct a verbal and graphical theory (the “fecundity-limitation within which he must incubate the embryos that he has sired with hypothesis”) about how constraints on the brooding space for em- one or more mates (14–17). This inversion from the familiar bryos probably truncate individual fecundity in male-pregnant and situation in female-pregnant animals apparently has translated in female-pregnant species in ways that should differentially influence some but not all syngnathid species into mating systems char- selection pressures for multiple mating by males or by females. We acterized by “sex-role reversal” (18, 19): a higher intensity of then review the empirical literature on genetically deduced rates of sexual selection on females than on males and an elaboration of fi multiple mating by the embryo-brooding parent in various fish spe- sexual secondary traits mostly in females. For one such pipe sh cies with three alternative categories of pregnancy: internal gesta- species, researchers also have documented that the sexual- tion by males, internal gestation by females, and external gestation selection gradient for females is steeper than that for males (20). More generally, fishes should be excellent subjects for as- (in nests) by males. Multiple mating by the brooding gender was fl common in all three forms of pregnancy.