Priorities for Syngnathid Research

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

A Polyandrous Society in Transition: a CASE STUDY of JAUNSAR-BAWAR

10/31/2014 A Polyandrous Society in transition: A CASE STUDY OF JAUNSAR-BAWAR SUBMITTED BY: Nargis Jahan IndraniTalukdar ShrutiChoudhary (Department of Sociology) (Delhi School of Economics) Abstract Man being a social animal cannot survive alone and has therefore been livingin groups or communities called families for ages. How these ‘families’ come about through the institution of marriage or any other way is rather an elaborate and an arduous notion. India along with its diverse people and societies offers innumerable ways by which people unite to come together as a family. Polyandry is one such way that has been prevalent in various regions of the sub-continent evidently among the Paharis of Himachal Pradesh, the Todas of Nilgiris, Nairs of Travancore and the Ezhavas of Malabar. While polyandrous unions have disappeared from the traditions of many of the groups and tribes, it is still practiced by some Jaunsaris—an ethnic group living in the lower Himalayan range—especially in the JaunsarBawar region of Uttarakhand.The concept of polyandry is so vast and mystifying that people who have just heard of the practice or the people who even did an in- depth study of it are confused in certain matters regarding it. This thesis aims at providing answers to many questions arising in the minds of people who have little or no knowledge of this subject. In this paper we have tried to find out why people follow this tradition and whether or not it has undergone transition. Also its various characteristics along with its socio-economic issues like the state and position of women in such a society and how the economic balance in a polyandrous family is maintained has been looked into. -

Polygynandry, Extra-Group Paternity and Multiple-Paternity Litters In

Molecular Ecology (2007) 16, 5294–5306 doi: 10.1111/j.1365-294X.2007.03571.x Polygynandry,Blackwell Publishing Ltd extra-group paternity and multiple-paternity litters in European badger (Meles meles) social groups HANNAH L. DUGDALE,*† DAVID W. MACDONALD,* LISA C. POPE† and TERRY BURKE† *Wildlife Conservation Research Unit, Department of Zoology, University of Oxford, Tubney House, Abingdon Road, Tubney OX13 5QL, UK, †Department of Animal and Plant Sciences, University of Sheffield, Western Bank, Sheffield S10 2TN, UK Abstract The costs and benefits of natal philopatry are central to the formation and maintenance of social groups. Badger groups, thought to form passively according to the resource dispersion hypothesis (RDH), are maintained through natal philopatry and delayed dispersal; however, there is minimal evidence for the functional benefits of such grouping. We assigned parentage to 630 badger cubs from a high-density population in Wytham Woods, Oxford, born between 1988 and 2005. Our methodological approach was different to previous studies; we used 22 microsatellite loci to assign parent pairs, which in combination with sibship inference provided a high parentage assignment rate. We assigned both parents to 331 cubs at ≥ 95% confidence, revealing a polygynandrous mating system with up to five mothers and five fathers within a social group. We estimated that only 27% of adult males and 31% of adult females bred each year, suggesting a cost to group living for both sexes. Any strong motivation or selection to disperse, however, may be reduced because just under half of the paternities were gained by extra-group males, mainly from neighbouring groups, with males displaying a mixture of paternity strategies. -

Mate Choice | Principles of Biology from Nature Education

contents Principles of Biology 171 Mate Choice Reproduction underlies many animal behaviors. The greater sage grouse (Centrocercus urophasianus). Female sage grouse evaluate males as sexual partners on the basis of the feather ornaments and the males' elaborate displays. Stephen J. Krasemann/Science Source. Topics Covered in this Module Mating as a Risky Behavior Major Objectives of this Module Describe factors associated with specific patterns of mating and life history strategies of specific mating patterns. Describe how genetics contributes to behavioral phenotypes such as mating. Describe the selection factors influencing behaviors like mate choice. page 882 of 989 3 pages left in this module contents Principles of Biology 171 Mate Choice Mating as a Risky Behavior Different species have different mating patterns. Different species have evolved a range of mating behaviors that vary in the number of individuals involved and the length of time over which their relationships last. The most open type of relationship is promiscuity, in which all members of a community can mate with each other. Within a promiscuous species, an animal of either gender may mate with any other male or female. No permanent relationships develop between mates, and offspring cannot be certain of the identity of their fathers. Promiscuous behavior is common in bonobos (Pan paniscus), as well as their close relatives, the chimpanzee (P. troglodytes). Bonobos also engage in sexual activity for activities other than reproduction: to greet other members of the community, to release social tensions, and to resolve conflicts. Test Yourself How might promiscuous behavior provide an evolutionary advantage for males? Submit Some animals demonstrate polygamous relationships, in which a single individual of one gender mates with multiple individuals of the opposite gender. -

Multiple Mating and Its Relationship to Alternative Modes of Gestation in Male-Pregnant Versus Female-Pregnant fish Species

Multiple mating and its relationship to alternative modes of gestation in male-pregnant versus female-pregnant fish species John C. Avise1 and Jin-Xian Liu Department of Ecology and Evolutionary Biology, University of California, Irvine, CA 92697 Contributed by John C. Avise, September 28, 2010 (sent for review August 20, 2010) We construct a verbal and graphical theory (the “fecundity-limitation within which he must incubate the embryos that he has sired with hypothesis”) about how constraints on the brooding space for em- one or more mates (14–17). This inversion from the familiar bryos probably truncate individual fecundity in male-pregnant and situation in female-pregnant animals apparently has translated in female-pregnant species in ways that should differentially influence some but not all syngnathid species into mating systems char- selection pressures for multiple mating by males or by females. We acterized by “sex-role reversal” (18, 19): a higher intensity of then review the empirical literature on genetically deduced rates of sexual selection on females than on males and an elaboration of fi multiple mating by the embryo-brooding parent in various fish spe- sexual secondary traits mostly in females. For one such pipe sh cies with three alternative categories of pregnancy: internal gesta- species, researchers also have documented that the sexual- tion by males, internal gestation by females, and external gestation selection gradient for females is steeper than that for males (20). More generally, fishes should be excellent subjects for as- (in nests) by males. Multiple mating by the brooding gender was fl common in all three forms of pregnancy. -

Factors Influencing the Diversification of Mating Behavior of Animals

International Journal of Zoology and Animal Biology ISSN: 2639-216X Factors Influencing the Diversification of Mating Behavior of Animals Afzal S1,2*, Shah SS1,2, Afzal T1, Javed RZ1, Batool F1, Salamat S1 and Review Article Raza A1 Volume 2 Issue 2 1Department of zoology, university of Narowal, Pakistan Received Date: January 28, 2019 Published Date: April 24, 2019 2Department of zoology, university of Punjab, Pakistan DOI: 10.23880/izab-16000145 *Corresponding author: Sabila Afzal, Department of zoology, University of Punjab, Pakistan, Email: [email protected] Abstract “Mating system” of a population refers to the general behavioral strategy employed in obtaining mates. In most of them one sex is more philopatric than the other. Reproductive enhancement through increased access to mates or resources and the avoidance of inbreeding are important in promoting sex differences in dispersal. In birds it is usually females which disperse more than males; in mammals it is usually males which disperse more than females. It is argued that the direction of the sex bias is a consequence of the type of mating system. Philopatry will favor the evolution of cooperative traits between members of the sedentary sex. It includes monogamy, Polygyny, polyandry and promiscuity. As an evolutionary strategy, mating systems have some “flexibility”. The existence of extra-pair copulation shows that mating systems identified on the basis of behavioral observations may not accord with actual breeding systems as determined by genetic analysis. Mating systems influence the effectiveness of the contraceptive control of pest animals. This method of control is most effective in monogamous and polygamous species. -

Genetic-Based Estimates of Adult Chinook Salmon Spawner Abundance from Carcass Surveys and Juvenile Out-Migrant Traps

Transactions of the American Fisheries Society 143:55–67, 2014 C American Fisheries Society 2014 ISSN: 0002-8487 print / 1548-8659 online DOI: 10.1080/00028487.2013.829122 ARTICLE Genetic-Based Estimates of Adult Chinook Salmon Spawner Abundance from Carcass Surveys and Juvenile Out-Migrant Traps Daniel J. Rawding, Cameron S. Sharpe,1 and Scott M. Blankenship*2 Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, 600 Capitol Way North, Olympia, Washington 98501-1091, USA Abstract Due to the challenges associated with monitoring in riverine environments, unbiased and precise spawner abun- dance estimates are often lacking for populations of Pacific salmon Oncorhynchus spp. listed under the Federal Endangered Species Act. We investigated genetic approaches to estimate the 2009 spawner abundance for a popu- lation of Columbia River Chinook Salmon Oncorhynchus tshawytscha via genetic mark–recapture and rarefaction curves. The marks were the genotyped carcasses collected from the spawning area during the first sampling event. The second sampling event consisted of a collection of juveniles from a downstream migrant trap located below the spawn- ing area. The parents that assigned to the juveniles through parentage analysis were considered the recaptures, which was a subset of the genotypes captured in the second sample. Using the Petersen estimator, the genetic mark–recapture spawner abundance estimates based on the binomial and hypergeometric models were 910 and 945 Chinook Salmon, respectively. These results were in agreement with independently derived spawner abundance estimates based on redd counts, area-under-the-curve methods, and carcass tagging based on the Jolly–Seber model. Using a rarefaction curve approach, which required only the juvenile offspring sample, our estimate of successful breeders was 781 fish. -

The Future of Polygamous Marriage in the Wake of Obergefell V

BEYE (DO NOT DELETE) 10/27/2016 7:29 PM THE MORE, THE MARRY-ER? THE FUTURE OF POLYGAMOUS MARRIAGE IN THE WAKE OF OBERGEFELL V. HODGES Amberly N. Beye* I. INTRODUCTION Since this nation’s inception, the United States Supreme Court has grappled with conceptualizing marriage in a way that reflects both this nation’s values and this nation’s Constitution. Conceptualizing marriage in a concordant way has proven to be a time-intensive task, leading the Supreme Court to analyze a variety of factual scenarios to determine which relationships fall within the protective confines of the Constitution. Over time, the Court’s perception of marriage has adapted to changing societal norms, encompassing issues such as race,1 poverty,2 and criminality.3 The limits of such adaptation were tested in recent years, when courts were faced with the constitutionality of same- sex marriage. The Supreme Court addressed the constitutionality of same-sex marriage and the related fundamental right to marry in Obergefell v. Hodges.4 In Obergefell, a class of homosexual plaintiffs claimed that their constitutional rights were violated when they were denied the right to marry their same-sex partner.5 Ultimately, on June 26, 2015, the Supreme Court ruled in the plaintiffs’ favor and held that a fundamental right to marry protects marriages between same-sex couples.6 In the wake of Obergefell, one of the main criticisms of the majority opinion is that it will reduce governmental restriction of marriage, * J.D. Candidate, 2017, Seton Hall University School of Law; B.A., summa cum laude, 2013, Drew University. -

Is Sexual Monomorphism a Predictor of Polygynandry? Evidence from a Social Mammal, the Collared Peccary Jennifer Daniel Cooper California State University

Southern Illinois University Carbondale OpenSIUC Publications Department of Zoology 4-2011 Is Sexual Monomorphism a Predictor of Polygynandry? Evidence from a Social Mammal, the Collared Peccary Jennifer Daniel Cooper California State University Peter M. Waser Purdue University Eric C. Hellgren Southern Illinois University Carbondale, [email protected] Timothy M. Gabor Northland Community & Technical College J. A. DeWoody Purdue University Follow this and additional works at: http://opensiuc.lib.siu.edu/zool_pubs Published in Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology, Vol. 65 No. 4 (April 2011). The original publication is available at 10.1007/s00265-010-1081-2 Recommended Citation Cooper, Jennifer D., Waser, Peter M., Hellgren, Eric C., Gabor, Timothy M. and DeWoody, J. A. "Is Sexual Monomorphism a Predictor of Polygynandry? Evidence from a Social Mammal, the Collared Peccary." (Apr 2011). This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Department of Zoology at OpenSIUC. It has been accepted for inclusion in Publications by an authorized administrator of OpenSIUC. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology IS SEXUAL MONOMORPHISM A PREDICTOR OF POLYGYNANDRY? EVIDENCE FROM A SOCIAL MAMMAL, THE COLLARED PECCARY For Review Only Journal: Behavioral Ecology and Sociobiology Manuscript ID: BES-10-0073.R1 Manuscript Type: Original Paper Date Submitted by the 02-Aug-2010 Author: Complete List of Authors: Cooper, Jennifer; Purdue University, Biological Sciences Waser, Peter; Purdue University, -

Variation in Reproductive Strategies Influences Post-Coital Experiences with Partners

Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology www.jsecjournal.comorg - 2010, 4(4), 254-264. Proceedings of the 4th Annual Meeting of the NorthEastern Evolutionary Psychology Society Original Article VARIATION IN REPRODUCTIVE STRATEGIES INFLUENCES POST-COITAL EXPERIENCES WITH PARTNERS Daniel J. Kruger* Institute for Social Research and School of Public Health, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor SusanSusan M. HughesHughes Department of Psychology, Albright College Abstract The Post-Coital Time Interval (PCTI) may be particularly important for pair-bonding and establishing relationship commitment. Women have greater incentives for establishing relationship commitment than men because of their greater necessary investment in offspring and the benefits of long-term paternal investment. Thus, sex differences in PCTI experiences may emerge based on sex differences in reproductive strategies. We generated 16 items to assess PCTI experiences and extracted three factors related to: 1) satisfaction and bonding, 2) a desire for more signals of bonding and commitment from one’s partner, and 3) romantic partners having a greater interest in talking about relationship issues. Consistent with our predictions, women’s satisfaction with PCTI experiences was inversely related to the extent to which they desired greater bonding and commitment signals from their partner, whereas men’s satisfaction with PCTI experiences was inversely related to the extent to which their partners’ had greater interests in talking about relationship issues. These dimensions were also related to other indicators of reproductive strategies, including attachment style. Keywords: Sex differences, reproductive strategies, commitment, attachment, life history Introduction This study investigated experiences with partners during the time interval immediately following sexual intercourse. There is a tremendous volume of research on human sexuality, and in recent decades, evolutionary researchers have generated a large body of literature on variance in human reproductive strategies (see Buss, 2005). -

Sue's Pdf Quark Setting

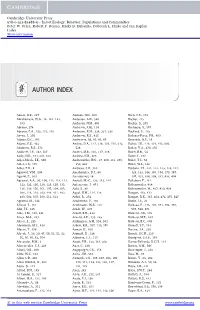

Cambridge University Press 978-0-521-83488-9 - Insect Ecology: Behavior, Populations and Communities Peter W. Price, Robert F. Denno, Micky D. Eubanks, Deborah L. Finke and Ian Kaplan Index More information AUTHOR INDEX Aanen, D.K., 227 Amman, G.D., 600 Bach, C.E., 152 Abrahamson, W.G., 16, 161, 162, Andersen, A.N., 580 Bacher, 275 165 Andersen, N.M., 401 Bacher, S., 275 Abrams, 274 Anderson, J.M., 114 Bachman, S., 567 Abrams, P.A., 195, 273, 276 Anderson, R.M., 336, 337, 338 Ba¨ckhed, F., 225 Acorn, J., 250 Anderson, R.S., 415 Badenes-Perez, F.R., 400 Adams, D.C., 203 Andersson, M., 82, 83, 87 Baerends, G.P., 29 Adams, E.S., 435 Andow, D.A., 127, 128, 179, 276, 513, Bailey, J.K., 426, 474, 475, 603 Adamson, R.S., 573 528 Bailey, V.A., 279, 356 Addicott, J.F., 242, 507 Andres, M.R., 116, 117, 118 Baker, R.R., 54 Addy, N.D., 574, 601, 602 Andrew, N.R., 566 Baker, I., 247 Adjei-Maafo, I.K., 530 Andrewartha, H.G., 27, 260, 261, 279, Baker, T.C., 53 Adler, L.S., 155 356, 404 Baker, W.L., 166 Adler, P.H., 8 Andrews, J.H., 310 Baldwin, I.T., 121, 122, 125, 126, 127, Agarwal, V.M., 506 Aneshansley, D.J., 48 129, 143, 144, 166, 174, 179, 187, Agnew, P., 369 Anonymous, 18 197, 201, 204, 208, 221, 492, 498 Agrawal, A.A., 99, 108, 114, 118, 121, Anstett, M.-C., 236, 243, 244 Ballabeni, P., 162 122, 125, 126, 128, 129, 130, 133, Antonovics, J., 471 Baltensweiler, 414 136, 139, 156, 161, 197, 204, 205, Aoki, S., 80 Baltensweiler, W., 407, 410, 424 208, 216, 219, 299, 444, 471, 492, Appel, H.M., 124, 128 Bangert, 465, 472 493, 502, 507, 509, 512, 513 -

POLYGYNANDRY in the DUSKY PIPEFISH <I>

UC Irvine UC Irvine Previously Published Works Title POLYGYNANDRY IN THE DUSKY PIPEFISH SYNGNATHUS FLORIDAE REVEALED BY MICROSATELLITE DNA MARKERS. Permalink https://escholarship.org/uc/item/14f2j0rs Journal Evolution, 51(5) ISSN 0014-3820 Authors Jones, Adam G Avise, John C Publication Date 1997-10-01 DOI 10.1111/j.1558-5646.1997.tb01484.x License https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/ 4.0 Peer reviewed eScholarship.org Powered by the California Digital Library University of California Evolution, 51(5),1997, pp. 1611-1622 POLYGYNANDRY IN THE DUSKY PIPEFISH SYNGNATHUS FLORIDAE REVEALED BY MICROSATELLITE DNA MARKERS ADAM G. JONES1 AND JOHN C. AVISE Department of Genetics, University of Georgia. Athens, Georgia 30602 Abstract.-In the dusky pipefish Syngnathus floridae, like other species in the family Syngnathidae, 'pregnant' males provide all post-zygotic care. Male pregnancy has interesting implications for sexual selection theory and the evolution of mating systems. Here, we employ microsatellite markers to describe the genetic mating system of S. floridae, compare the outcome with a previous report of genetic polyandry for the Gulf pipefish S. scovelli, and consider possible associations between the mating system and degree of sexual dimorphism in these species. Twenty-two pregnant male dusky pipefish from one locale in the northern Gulf of Mexico were analyzed genetically, together with subsamples of 42 embryos from each male's brood pouch. Adult females also were assayed. The genotypes observed in these samples document that cuckoldry by males did not occur; males often receive eggs from multiple females during the course of a pregnancy (six males had one mate each, 13 had two mates, and three had three mates); embryos from different females are segregated spatially within a male's brood pouch; and a female's clutch of eggs often is divided among more than one male. -

Partible Paternity and Human Reproductive Behavior

PARTIBLE PATERNITY AND HUMAN REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOR _______________________________________ A Dissertation presented to the Faculty of the Graduate School at the University of Missouri-Columbia _______________________________________________________ In Partial Fulfillment of the Requirements for the Degree Doctor of Philosophy _____________________________________________________ by RYAN M. ELLSWORTH DECEMBER 2014 i The undersigned, appointed by the dean of the Graduate School, have examined the dissertation entitled PARTIBLE PATERNITY AND HUMAN REPRODUCTIVE BEHAVIOR presented by Ryan Ellsworth, a candidate for the degree of doctor of philosophy, and hereby certify that, in their opinion, it is worthy of acceptance. _____________________________________ Professor Robert Walker _____________________________________ Professor Craig Palmer _____________________________________ Professor Mark Flinn _____________________________________ Professor David Geary ii ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS First and foremost thanks to my advisor, Robert Walker, and my former advisor, Craig Palmer, as well as Mark Flinn and David Geary. Special recognition to my collaborators and co-authors, Rob Walker, Drew Bailey, Kim Hill, Magdalena Hurtado, and Mary Shenk. Many thanks to Lada Micheas of the Social Science Statistics Center for invaluable assistance with the statistical analyses in chapter 3. I thank Dennis, Anne, Jill, Alyssa, Tilly, and Erin for encouragement and support throughout my graduate career, and for enduring me the last several years. iii TABLE OF CONTENTS