Alan Ladd Jr. V. Warner Bros. Entertainment, Inc. Combined

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Pr-Dvd-Holdings-As-Of-September-18

CALL # LOCATION TITLE AUTHOR BINGE BOX COMEDIES prmnd Comedies binge box (includes Airplane! --Ferris Bueller's Day Off --The First Wives Club --Happy Gilmore)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX CONCERTS AND MUSICIANSprmnd Concerts and musicians binge box (Includes Brad Paisley: Life Amplified Live Tour, Live from WV --Close to You: Remembering the Carpenters --John Sebastian Presents Folk Rewind: My Music --Roy Orbison and Friends: Black and White Night)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX MUSICALS prmnd Musicals binge box (includes Mamma Mia! --Moulin Rouge --Rodgers and Hammerstein's Cinderella [DVD] --West Side Story) [videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. BINGE BOX ROMANTIC COMEDIESprmnd Romantic comedies binge box (includes Hitch --P.S. I Love You --The Wedding Date --While You Were Sleeping)[videorecording] / Princeton Public Library. DVD 001.942 ALI DISC 1-3 prmdv Aliens, abductions & extraordinary sightings [videorecording]. DVD 001.942 BES prmdv Best of ancient aliens [videorecording] / A&E Television Networks History executive producer, Kevin Burns. DVD 004.09 CRE prmdv The creation of the computer [videorecording] / executive producer, Bob Jaffe written and produced by Donald Sellers created by Bruce Nash History channel executive producers, Charlie Maday, Gerald W. Abrams Jaffe Productions Hearst Entertainment Television in association with the History Channel. DVD 133.3 UNE DISC 1-2 prmdv The unexplained [videorecording] / produced by Towers Productions, Inc. for A&E Network executive producer, Michael Cascio. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again [videorecording] / producers, Simon Harries [and three others] director, Ashok Prasad [and five others]. DVD 158.2 WEL prmdv We'll meet again. Season 2 [videorecording] / director, Luc Tremoulet producer, Page Shepherd. -

2013 Movie Catalog © Warner Bros

1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney © TriStar Pictures © Warner Bros. © NBC Universal © Columbia Pictures Industries, ©Inc. Summit Entertainment 2013 Movie Catalog Movie 2013 Inc. Pictures, Motion Swank 1-800-876-5577 www.swank.com MOVIES Swank Motion Pictures,Inc. Swank Motion 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie © New Line Cinema © 2013 Disney © Columbia Pictures Industries, Inc. © Warner Bros. © 2013 Disney/Pixar © Summit Entertainment Promote Your movie event! Ask about FREE promotional materials to help make your next movie event a success! 2013 Movie Catalog 2013 Movie Catalog TABLE OF CONTENTS New Releases ......................................................... 1-34 Swank has rights to the largest collection of movies from the top Coming Soon .............................................................35 Hollywood & independent studios. Whether it’s blockbuster movies, All Time Favorites .............................................36-39 action and suspense, comedies or classic films,Swank has them all! Event Calendar .........................................................40 Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm Classics ...................................................................41-42 Disney 2012 © Date Night ........................................................... 43-44 TABLE TENT Sat., June 16th - 8:00pm TM & © Marvel & Subs 1-800-876-5577 | www.swank.com Environmental Films .............................................. 45 FLYER Faith-Based -

HOLLYWOOD – the Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition

HOLLYWOOD – The Big Five Production Distribution Exhibition Paramount MGM 20th Century – Fox Warner Bros RKO Hollywood Oligopoly • Big 5 control first run theaters • Theater chains regional • Theaters required 100+ films/year • Big 5 share films to fill screens • Little 3 supply “B” films Hollywood Major • Producer Distributor Exhibitor • Distribution & Exhibition New York based • New York HQ determines budget, type & quantity of films Hollywood Studio • Hollywood production lots, backlots & ranches • Studio Boss • Head of Production • Story Dept Hollywood Star • Star System • Long Term Option Contract • Publicity Dept Paramount • Adolph Zukor • 1912- Famous Players • 1914- Hodkinson & Paramount • 1916– FP & Paramount merge • Producer Jesse Lasky • Director Cecil B. DeMille • Pickford, Fairbanks, Valentino • 1933- Receivership • 1936-1964 Pres.Barney Balaban • Studio Boss Y. Frank Freeman • 1966- Gulf & Western Paramount Theaters • Chicago, mid West • South • New England • Canada • Paramount Studios: Hollywood Paramount Directors Ernst Lubitsch 1892-1947 • 1926 So This Is Paris (WB) • 1929 The Love Parade • 1932 One Hour With You • 1932 Trouble in Paradise • 1933 Design for Living • 1939 Ninotchka (MGM) • 1940 The Shop Around the Corner (MGM Cecil B. DeMille 1881-1959 • 1914 THE SQUAW MAN • 1915 THE CHEAT • 1920 WHY CHANGE YOUR WIFE • 1923 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS • 1927 KING OF KINGS • 1934 CLEOPATRA • 1949 SAMSON & DELILAH • 1952 THE GREATEST SHOW ON EARTH • 1955 THE 10 COMMANDMENTS Paramount Directors Josef von Sternberg 1894-1969 • 1927 -

Tandem Productions & Bernero Productions in Coproduction With

Tandem Productions & Bernero Productions in coproduction with TF1 Production and in association with Sony Pictures Television Networks present A WORLD WITHOUT BORDERS NEEDS JUSTICE WITHOUT BORDERS WILLIAM FICHTNER MARC LAVOINE GABRIELLA PESSION TOM WLASCHIHA RICHARD FLOOD is CARL HICKMAN is LOUIS DANIEL is EVA VITTORIA is SEBASTIAN BERGER is TOMMY MCCONNELL (Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles, (The Good Thief, Deception) (Rossella, Capri) (Game of Thrones, Brideshead Revisited) (Titanic: Blood & Steel, Three Wise Women) Prison Break) Introducing new recurring guest stars in Season 2 LARA ROSSI and DONALD SUTHERLAND CARRIE-ANNE MOSS and RAY STEVENSON is ARABELA SEEGER is MICHEL DORN as AMANDA ANDREWS as MILES LENNON (Life of Crime, Murder: Joint Enterprise) (The Hunger Games, (Vegas, Matrix, Chocolat) (Dexter, The Book of Eli) The Pillars of the Earth, Path to War) THE STORY THE FACTS Crossing Lines is a unique, global action/crime series that taps into the charter of the International TITLE: CROSSING LINES Criminal Court (ICC), to mandate a special crime unit functioning as a European-based FBI, to GENRE: ACTION CRIME DRAMA investigate serialized crimes that cross over European borders and to hunt down and bring criminals to justice. FORMAT: 22 x APPROX. 45 MIN. SERIES BUDGET: USD 3 MILLION/EPISODE It is also a story of redemption and revenge. CARL HICKMAN, a wounded and disgraced New York cop, pulled from the edge by a group of unlikely saviors – LOUIS DANIEL, heading an elite cross PRODUCTION COMPANIES: border police unit, hunting down the world’s most brutal criminals, but ultimately seeking revenge for TANDEM PRODUCTIONS his son’s murder. -

Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema's Representation of Non

University of Southampton Research Repository Copyright © and Moral Rights for this thesis and, where applicable, any accompanying data are retained by the author and/or other copyright owners. A copy can be downloaded for personal non-commercial research or study, without prior permission or charge. This thesis and the accompanying data cannot be reproduced or quoted extensively from without first obtaining permission in writing from the copyright holder/s. The content of the thesis and accompanying research data (where applicable) must not be changed in any way or sold commercially in any format or medium without the formal permission of the copyright holder/s. When referring to this thesis and any accompanying data, full bibliographic details must be given, e.g. Thesis: Author (Year of Submission) "Full thesis title", University of Southampton, name of the University Faculty or School or Department, PhD Thesis, pagination. Data: Author (Year) Title. URI [dataset] University of Southampton Faculty of Arts and Humanities Film Studies Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. DOI: by Eliot W. Blades Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy May 2020 University of Southampton Abstract Faculty of Arts and Humanities Department of Film Studies Thesis for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy Complicated Views: Mainstream Cinema’s Representation of Non-Cinematic Audio/Visual Technologies after Television. by Eliot W. Blades This thesis examines a number of mainstream fiction feature films which incorporate imagery from non-cinematic moving image technologies. The period examined ranges from the era of the widespread success of television (i.e. -

The Norman Conquest: the Style and Legacy of All in the Family

View metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk brought to you by CORE provided by Boston University Institutional Repository (OpenBU) Boston University OpenBU http://open.bu.edu Theses & Dissertations Boston University Theses & Dissertations 2016 The Norman conquest: the style and legacy of All in the Family https://hdl.handle.net/2144/17119 Boston University BOSTON UNIVERSITY COLLEGE OF COMMUNICATION Thesis THE NORMAN CONQUEST: THE STYLE AND LEGACY OF ALL IN THE FAMILY by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE B.A., Emerson College, 2013 Submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Fine Arts 2016 © 2016 by BAILEY FRANCES LIZOTTE All rights reserved Approved by First Reader ___________________________________________________ Deborah L. Jaramillo, Ph.D. Assistant Professor of Film and Television Second Reader ___________________________________________________ Michael Loman Professor of Television DEDICATION This thesis is dedicated to Jean Lizotte, Nicholas Clark, and Alvin Delpino. iv ACKNOWLEDGMENTS First, I’m exceedingly thankful for the guidance and patience of my thesis advisor, Dr. Deborah Jaramillo, whose investment and dedication to this project allowed me to explore a topic close to my heart. I am also grateful for the guidance of my second reader, Michael Loman, whose professional experience and insight proved invaluable to my work. Additionally, I am indebted to all of the professors in the Film and Television Studies program who have facilitated my growth as a viewer and a scholar, especially Ray Carney, Charles Warren, Roy Grundmann, and John Bernstein. Thank you to David Kociemba, whose advice and encouragement has been greatly appreciated throughout this entire process. A special thank you to my fellow graduate students, especially Sarah Crane, Dani Franco, Jess Lajoie, Victoria Quamme, and Sophie Summergrad. -

Scriptedpifc-01 Banijay Aprmay20.Indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights Presents… Bäckström the Hunt for a Killer We Got This Thin Ice

Insight on screen TBIvision.com | April/May 2020 Television e Interview Virtual thinking The Crown's Andy Online rights Business Harries on what's companies eye next for drama digital disruption TBI International Page 10 Page 12 pOFC TBI AprMay20.indd 1 20/03/2020 20:25 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. sadistic murder case that had remained unsolved for 16 years. most infamous unsolved murder case? climate change, geo-politics and Arctic exploitation. Bang The Gulf GR5: Into The Wilderness Rebecka Martinsson When a young woman vanishes without a trace In a brand new second season, a serial killer targets Set on New Zealand’s Waiheke Island, Detective Jess Savage hiking the famous GR5 trail, her friends set out to Return of the riveting crime thriller based on a group of men connected to a historic sexual assault. investigates cases while battling her own inner demons. solve the mystery of her disappearance. the best-selling novels by Asa Larsson. banijayrights.com ScriptedpIFC-01 Banijay AprMay20.indd 2 10/03/2020 16:54 Banijay Rights presents… Bäckström The Hunt For A Killer We Got This Thin Ice Crime drama series based on the books by Leif GW Persson Based on a true story, a team of police officers set out to solve a How hard can it be to solve the world’s Suspense thriller dramatising the burning issues of following the rebellious murder detective Evert Bäckström. -

Aspects of Film Noir: Alan Ladd in the 40'S

The Museum of Modern Art 50th Anniversary NO. 38 •JO RELEASE ON OR BEFORE JULY 11, 1980 "ASPECTS OF FILM NOIR: ALAN LAPP IN THE 40*5" OPENS AT MoMA ON JULY 11, 1980 A series of four important Alan Ladd films forms ASPECTS OF FILM NOIR: ALAN LADD IN THE 40'S, an exhibition running from July 11 through July 15, 1980 at The Museum of Modern Art. To be shown in the series are: THIS GUN FOR HIRE, Ladd's first starring role; THE GLASS KEY; THE BLUE DAHLIA; and the 1949 Paramount production of the F. Scott Fitzgerald classic, THE GREAT GATSBY. The films will be shown in 35mm studio prints made available by Universal/MCA and the UCLA Film Archives. Notes from The Museum's Department of Film indicate that "During the 1940's Hollywood studios produced a large number of crime melodramas whose stylistic con sistency has since been given the name of 'Film Noir'. These shadowy and urbane films not only commanded consummate studio craftsmanship, but enabled a charismatic group of performers to express the tensions that provided the thematic content for the 'Film Noir'. At Paramount Pictures during the 1940's perhaps the emblematic figure of the 'Film Noir' was Alan Ladd." The series opens with THIS GUN FOR HIRE at 8:30 PM on Friday, July 11 (to be repeated at 6 PM on Sunday, July 13). The film was directed by Frank Tuttle in 1942 with Ladd, Veronica Lake and Robert Preston and runs 81 minutes. THIS GUN FOR HIRE was the film that launched Ladd's career. -

Master Class with Douglas Trumbull: Selected Filmography 1 the Higher Learning Staff Curate Digital Resource Packages to Complem

Master Class with Douglas Trumbull: Selected Filmography The Higher Learning staff curate digital resource packages to complement and offer further context to the topics and themes discussed during the various Higher Learning events held at TIFF Bell Lightbox. These filmographies, bibliographies, and additional resources include works directly related to guest speakers’ work and careers, and provide additional inspirations and topics to consider; these materials are meant to serve as a jumping-off point for further research. Please refer to the event video to see how topics and themes relate to the Higher Learning event. * mentioned or discussed during the master class ^ special effects by Douglas Trumbull Early Special Effects Films (Pre-1968) The Execution of Mary, Queen of Scots. Dir. Alfred Clark, 1895, U.S.A. 1 min. Production Co.: Edison Manufacturing Company. The Vanishing Lady (Escamotage d’une dame au théâtre Robert Houdin). Dir. Georges Méliès, 1896, France. 1 min. Production Co.: Théâtre Robert-Houdin. A Railway Collision. Dir. Walter R. Booth, 1900, U.K. 1 mins. Production Co.: Robert W. Paul. A Trip to the Moon (Le voyage dans la lune). Dir. Georges Méliès, 1902, France. 14 mins. Production Co.: Star-Film. A Trip to Mars. Dir. Ashley Miller, 1910, U.S.A. 5 mins. Production Co.: Edison Manufacturing Company. The Conquest of the Pole (À la conquête de pôle). Dir. Georges Méliès, 1912, France. 33 mins. Production Co.: Star-Film. *Intolerance: Love’s Struggle Throughout the Ages. Dir. D.W. Griffith, 1916, U.S.A. 197 mins. Production Co.: Triangle Film Corporation / Wark Producing. The Ten Commandments. -

Botany Bay on Talking Pictures TV Stars: Alan Ladd, James Mason and Patricia Medina

Talking Pictures TV www.talkingpicturestv.co.uk Highlights for week beginning SKY 328 | FREEVIEW 81 Mon 11th May 2020 FREESAT 306 | VIRGIN 445 Botany Bay on Talking Pictures TV Stars: Alan Ladd, James Mason and Patricia Medina. Directed by John Farrow, released in 1953. In 1787 prisoners are shipped from Newgate Jail on Charlotte to found a new penal colony in Botany Bay, New South Wales. Amongst them is an American medical student who was wrongly imprisoned. During the journey he clashes with the villainous Captain, and is soon plotting mutiny against him. Airs on Saturday 16th May at 9pm. Monday 11th May 1:10pm Tuesday 12th May 10pm The Importance of being Earnest The Best of Everything (1959) (1952) Drama, directed by Jean Negulesco. Comedy, directed by Anthony Stars: Joan Crawford, Louis Jourdan, Asquith. Stars: Michael Redgrave, Hope Lange, Stephen Boyd and Suzy Richard Wattis, Michael Denison, Parker. A story about the lives of three Edith Evans, Margaret Rutherford. women who share a small apartment Algernon discovers that his friend in New York City. Ernest has a fictional brother and Wednesday 13th May 11:30am decides to impersonate the brother. Scotland Yard Investigator (1945) Monday 11th May 5:30pm Directed by George Blair. Hue and Cry (1947) Stars: C. Aubrey Smith, Stephanie Adventure. Director: Charles Crichton. Bachelor, Erich von Stroheim. During Stars: Alastair Sim, Frederick Piper, the Second World War the Mona Lisa Harry Fowler. A gang of street boys is moved to a London gallery, where a foil a crook who sends commands for German art collector tries to steal it. -

Humanity and Heroism in Blade Runner 2049 Ridley

Through Galatea’s Eyes: Humanity and Heroism in Blade Runner 2049 Ridley Scott’s 1982 Blade Runner depicts a futuristic world, where sophisticated androids called replicants, following a replicant rebellion, are being tracked down and “retired” by officers known as “blade runners.” The film raises questions about what it means to be human and memories as social conditioning. In the sequel, Blade Runner 2049, director Denis Villeneuve continues to probe similar questions, including what gives humans inalienable worth and at what point post-humans participate in this worth. 2049 follows the story of a blade runner named K, who is among the model of replicants designed to be more obedient. Various clues cause K to suspect he may have been born naturally as opposed to manufactured. Themes from the Pinocchio story are interwoven in K’s quest to discover if he is, in fact, a “real boy.” At its core Pinocchio is a Pygmalion story from the creature’s point of view. It is apt then that most of 2049 revolves around replicants, with humans as the supporting characters. By reading K through multiple mythological figures, including Pygmalion, Telemachus, and Oedipus, this paper will examine three hallmarks of humanity suggested by Villeneuve’s film: natural birth, memory, and self-sacrifice. These three qualities mark the stages of a human life but particularly a mythological hero’s life. Ultimately, only one of these can truly be said to apply to K, but it will be sufficient for rendering him a “real boy” nonetheless. Although Pinocchio stories are told from the creatures’ point of view, they are still based on what human authors project onto the creature. -

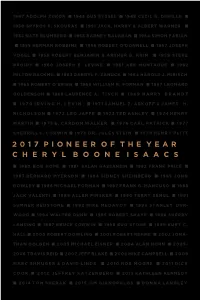

2017 Pioneer of the Year C H E R Y L B O O N E I S a A

1947 ADOLPH ZUKOR n 1948 GUS EYSSEL n 1949 CECIL B. DEMILLE n 1950 SPYROS P. SKOURAS n 1951 JACK, HARRY & ALBERT WARNER n 1952 NATE BLUMBERG n 1953 BARNEY BALABAN n 1954 SIMON FABIAN n 1955 HERMAN ROBBINS n 1956 ROBERT O’DONNELL n 1957 JOSEPH VOGEL n 1958 ROBERT BENJAMIN & ARTHUR B. KRIM n 1959 STEVE BROIDY n 1960 JOSEPH E. LEVINE n 1961 ABE MONTAGUE n 1962 MILTON RACKMIL n 1963 DARRYL F. ZANUCK n 1964 HAROLD J. MIRISCH n 1965 ROBERT O’BRIEN n 1966 WILLIAM R. FORMAN n 1967 LEONARD GOLDENSON n 1968 LAURENCE A. TISCH n 1969 HARRY BRANDT n 1970 IRVING H. LEVIN n 1971 SAMUEL Z. ARKOFF & JAMES H . NICHOLSON n 1972 LEO JAFFE n 1973 TED ASHLEY n 1974 HENRY MARTIN n 1975 E. CARDON WALKER n 1976 CARL PATRICK n 1977 SHERRILL C. CORWIN n 1978 DR. JULES STEIN n 1979 HENRY PLITT 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS n 1980 BOB HOPE n 1981 SALAH HASSANEIN n 1982 FRANK PRICE n 1983 BERNARD MYERSON n 1984 SIDNEY SHEINBERG n 1985 JOHN ROWLEY n 1986 MICHAEL FORMAN n 1987 FRANK G. MANCUSO n 1988 JACK VALENTI n 1989 ALLEN PINSKER n 1990 TERRY SEMEL n 1991 SUMNER REDSTONE n 1992 MIKE MEDAVOY n 1993 STANLEY DUR- WOOD n 1994 WALTER DUNN n 1995 ROBERT SHAYE n 1996 SHERRY LANSING n 1997 BRUCE CORWIN n 1998 BUD STONE n 1999 KURT C. HALL n 2000 ROBERT DOWLING n 2001 ROBERT REHME n 2002 JONA- THAN DOLGEN n 2003 MICHAEL EISNER n 2004 ALAN HORN n 2005– 2006 TRAVIS REID n 2007 JEFF BLAKE n 2008 MIKE CAMPBELL n 2009 MARC SHMUGER & DAVID LINDE n 2010 ROB MOORE n 2011 DICK COOK n 2012 JEFFREY KATZENBERG n 2013 KATHLEEN KENNEDY n 2014 TOM SHERAK n 2015 JIM GIANOPULOS n DONNA LANGLEY 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR CHERYL BOONE ISAACS 2017 PIONEER OF THE YEAR Welcome On behalf of the Board of Directors of the Will Rogers Motion Picture Pioneers Foundation, thank you for attending the 2017 Pioneer of the Year Dinner.