Colonial Charters and Early State Constitutions

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary" (1976). Faculty Publications. 1595. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1595 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Spring 1976 Number 2 RUNNYMEDE REVISITED: BICENTENNIAL REFLECTIONS ON A 750TH ANNIVERSARY* WILLIAM F. SWINDLER" I. MAGNA CARTA, 1215-1225 America's bicentennial coincides with the 750th anniversary of the definitive reissue of the Great Charter of English liberties in 1225. Mile- stone dates tend to become public events in themselves, marking the be- ginning of an epoch without reference to subsequent dates which fre- quently are more significant. Thus, ten years ago, the common law world was astir with commemorative festivities concerning the execution of the forced agreement between King John and the English rebels, in a marshy meadow between Staines and Windsor on June 15, 1215. Yet, within a few months, John was dead, and the first reissues of his Charter, in 1216 and 1217, made progressively more significant changes in the document, and ten years later the definitive reissue was still further altered.' The date 1225, rather than 1215, thus has a proper claim on the his- tory of western constitutional thought-although it is safe to assume that few, if any, observances were held vis-a-vis this more significant anniver- sary of Magna Carta. -

Amicus Brief

No. 20-855 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARYLAND SHALL ISSUE, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. LAWRENCE HOGAN, IN HIS CAPACITY OF GOVERNOR OF MARYLAND, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOSEPH G.S. GREENLEE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION 1215 K Street, 17th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 378-5785 [email protected] January 28, 2021 Counsel of Record ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................ i INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ............... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 1 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Personal property is entitled to full consti- tutional protection ....................................... 3 II. Since medieval England, the right to prop- erty—both personal and real—has been protected against arbitrary seizure -

The American Experiment

The American2 Experiment Assignment government, where majority desires have an even greater impact on the government. This lesson is based on information in the following Although these ideas are associated with the devel- text selections and video. Carefully read and review opment of the U.S. Constitution, they have their roots all of the materials before taking the practice test. in the preceding colonial and revolutionary experi- The key terms, focus points, and practice test are in- ences in America. The colonists’ English heritage had tended to help ensure mastery of the essential politi- stressed the ideas of both limited government and cal issues surrounding the background and creation self-government. To a large extent, the American rev- of the U.S. Constitution. olutionaries were seeking to retain what they had tra- ditionally understood to be their rights as Text: Chapter 2, “Constitutional Democracy: Pro- Englishmen. Controversy between the American col- moting Liberty and Self-Government,” pp. onists and the English developed in the aftermath of 37–48 the French and Indian War, when the British govern- ment sought to impose several new taxes in order to Declaration of Independence, Appendix A raise revenue. The British first enacted the Stamp Act, then the Townshend Act, and then a tax on tea. Video: “The American Experiment” Because they had no representatives in the English Parliament, the colonists were convinced that these taxes violated the principle of “no taxation without Overview representation,” a right recognized by Englishmen. The colonists met together to articulate their griev- Events like the Watergate break-in during the Nixon ances against the British crown at the First Continen- Administration demonstrate that Americans still tal Congress in Philadelphia in 1774. -

Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776

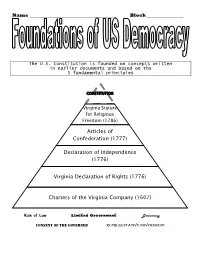

Name ______________________________________ Block ________________ The U.S. Constitution is founded on concepts written in earlier documents and based on the 5 fundamental principles CONSTITUTION Virginia Statute for Religious Freedom (1786) Articles of Confederation (1777) Declaration of Independence (1776) Virginia Declaration of Rights (1776) Charters of the Virginia Company (1607) Rule of Law Limited Government Democracy Consent of the Governed Representative Government Anticipation guide Founding Documents Vocabulary Amend Constitution Independence Repeal Colony Affirm Grievance Ratify Unalienable Rights Confederation Charter Delegate Guarantee Declaration Colonist Reside Territory (land) politically controlled by another country A person living in a settlement/colony Written document granting land and authority to set up colonial governments To make a powerful statement that is official Freedom from the control of others A complaint Freedoms that everyone is born with and cannot be taken away (Life, Liberty, Pursuit of Happiness) To promise To vote to approve To change Representatives/elected officials at a meeting A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose To verify that something is true To cancel a law To stay in a place A written plan of government Foundations of American Democracy Across 1. Territory politically controlled by another country 2. To vote to approve 4. Freedom from the control of others 5. Representatives/elected officials at a meeting 8. A complaint 10. To verify that something is true 11. To make a powerful statement that is official 12. To cancel a law 13. To stay in a place 14. A written plan of government Down 1. A group of individuals or states who band together for a common purpose 3. -

The Origins of the Pursuit of Happiness Carli N

Washington University Jurisprudence Review Volume 7 | Issue 2 2015 The Origins of the Pursuit of Happiness Carli N. Conklin Follow this and additional works at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence Part of the Jurisprudence Commons, Law and Philosophy Commons, Law and Society Commons, Legal History Commons, Legal Theory Commons, Political Theory Commons, Public Law and Legal Theory Commons, and the Rule of Law Commons Recommended Citation Carli N. Conklin, The Origins of the Pursuit of Happiness, 7 Wash. U. Jur. Rev. 195 (2015). Available at: https://openscholarship.wustl.edu/law_jurisprudence/vol7/iss2/6 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Law School at Washington University Open Scholarship. It has been accepted for inclusion in Washington University Jurisprudence Review by an authorized administrator of Washington University Open Scholarship. For more information, please contact [email protected]. THE ORIGINS OF THE PURSUIT OF HAPPINESS CARLI N. CONKLIN ABSTRACT Scholars have long struggled to define the meaning of the phrase “the pursuit of happiness” in the Declaration of Independence. The most common understandings suggest either that the phrase is a direct substitution for John Locke’s conception of property or that the phrase is a rhetorical flourish that conveys no substantive meaning. Yet, property and the pursuit of happiness were listed as distinct—not synonymous— rights in eighteenth-century writings. Furthermore, the very inclusion of “the pursuit of happiness” as one of only three unalienable rights enumerated in the Declaration suggests that the drafters must have meant something substantive when they included the phrase in the text. -

American Ideas About the Rights of Man and How a Government Should Operate

American Ideas About the Rights of Man and How A Government Should Operate The Framers of the Constitution were inspired by the following documents and people. Magna Carta (1215) In early 1200’s King John of England began to treat his nobles in ways they felt were unfair. He taxed without asking permission, and put them in jail and took their property without a trial if they refused to pay the taxes. Magna Carta (1215) Many of the Nobles banded together to resist the king’s efforts to take away rights they thought were theirs. They met the king in a place called Runnymeade and forced him to sign a document called the Magna Carta or Great Charter. Magna Carta (1215) The Magna Carta put in writing ideas that are important to our ideas of democracy and rights. 1. Laws that even Kings have to obey. 2. No taxation except by legal means. 3. Right to a fair trial. Mayflower Compact (1620) When the Puritans left England to come to America to escape religious persecution, they were blown off course and landed in Massachusetts, which was outside a colony where there was government. They signed an agreement to establish a government and abide by the laws they made. Mayflower Compact (1630) The Mayflower Compact established these ideas: 1. Established self government and majority rule. 2. A King is not necessary to have laws. 3. Laws can be made by the people for the good of the colony. English Bill of Rights (1689) King James II dismissed parliament and tried to restrict the rights of people in England. -

The Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV, 37 Case W

Case Western Reserve Law Review Volume 37 | Issue 4 1987 The rP ivileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV David S. Bogen Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev Part of the Law Commons Recommended Citation David S. Bogen, The Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV, 37 Case W. Res. L. Rev. 794 (1987) Available at: https://scholarlycommons.law.case.edu/caselrev/vol37/iss4/8 This Symposium is brought to you for free and open access by the Student Journals at Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Case Western Reserve Law Review by an authorized administrator of Case Western Reserve University School of Law Scholarly Commons. THE PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES CLAUSE OF ARTICLE IV David S. Bogen* The Privileges and Immunities Clause ofArticle IV is deeply rooted in the histori- cal context of English law. It developed from colonial charter provisions and the position of the colonists as subjects of a common king, evolved as the colonies ex- panded, survived the Revolutionary War in the Articles of Confederation and was eventually adopted in the Constitution. This Article traces the history of the Privileges and Immunities Clause in order to elaborate on the originalintent embodied in its language. ProfessorBogen states that the clause did not embody natural law concepts, but was solely concerned with creating a national citizenship. He contends thatfear of a naturallaw interpretationhas incorrectlyprevented the Courtfrom finding the clause applicable to citizens in the state where they reside. He suggests that a full examina- tion of the historical origin of the clause could lead to a more concrete basis for judicial interpretation. -

DBQ Sample Essays

AP US History® DBQ Sample Essays Created by: Chris Averill AP® is a trademark registered by the College Board, which is not affliated with, and does not endorse, this website. Use these sample essays to better understand how graders evaluate the DBQ Rubric. There are three essays: Sample A – 7 Points Sample B – 4 Points Sample C – 1 Point Sample A – 7 of 7 points There is little doubt that the pushers oF Revolution during the two decades beFore 1776 had numerous motives underlying their cause. The base Foundation of the movement to revolution was a belieF amongst many colonists that they enjoyed Englishmen’s rights just liKe Englishmen in England. These ideas were spawned by the Enlightenment Era of the early 18th and were the philosophical underpinnings of the movement. However, the most signiFicant cause of the movement towards independence were the economic beneFits that such a revolution might bring - An end to British taxes and the ability to be economically selF-suFFicient. They would enjoy For themselves the wealth that they believed was being stolen by British manufacturers. These two underlying Forces were brought into clear Focus when a series of perceived tyrannical events by Britain occurred in the two decades beFore the revolution. Britain passed legislation that taxed them and violated their inalienable rights. Fundamentally, the colonists had always thought oF themselves as economically independent. Since the day the English landed at Jamestown and became economically viable with tobacco they were in many ways independent from England. England, like other European monarchies oF the 18th century, had created the mercantile system of trade between the colonies and the mother country whereby they sold manuFactured goods to the colonists in exchange For colonial agricultural goods and raw materials. -

Origins of the Privileges and Immunities of State Citizenship Under Article IV Stewart Jay University of Washington School of Law

Loyola University Chicago Law Journal Volume 45 Article 1 Issue 1 2013 Fall 2013 Origins of the Privileges and Immunities of State Citizenship under Article IV Stewart Jay University of Washington School of Law Follow this and additional works at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj Part of the Constitutional Law Commons Recommended Citation Stewart Jay, Origins of the Privileges and Immunities of State Citizenship under Article IV, 45 Loy. U. Chi. L. J. 1 (2013). Available at: http://lawecommons.luc.edu/luclj/vol45/iss1/1 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by LAW eCommons. It has been accepted for inclusion in Loyola University Chicago Law Journal by an authorized administrator of LAW eCommons. For more information, please contact [email protected]. ORIGINS OF THE PRIVILEGES AND IMMUNITIES OF STATE CITIZENSHIP.DOCX (DO NOT DELETE) 10/17/2013 10:46 AM Origins of the Privileges and Immunities of State Citizenship under Article IV Stewart Jay* The Privileges and Immunities Clause of Article IV provides: “The Citizens of each State shall be entitled to all Privileges and Immunities of Citizens in the several States.” According to Alexander Hamilton, the clause was “the basis of the union,” which may seem odd given its minor significance in modern constitutional law. Part of the reason for its relative unimportance today is the development of constitutional doctrines unforeseeable in the eighteenth century: the invention of the Dormant Commerce Clause and the enactment of the Fourteenth Amendment, which prohibit much of the interstate discrimination that Article IV’s clause was intended to prevent. -

The American Revolution

HISTORY AND GEOGRAPHY The American Revolution Reader George Washington Paul Revere’s ride Crispus Attucks Stamp Act Crisis THIS BOOK IS THE PROPERTY OF: STATE Book No. PROVINCE Enter information COUNTY in spaces to the left as PARISH instructed. SCHOOL DISTRICT OTHER CONDITION Year ISSUED TO Used ISSUED RETURNED PUPILS to whom this textbook is issued must not write on any page or mark any part of it in any way, consumable textbooks excepted. 1. Teachers should see that the pupil’s name is clearly written in ink in the spaces above in every book issued. 2. The following terms should be used in recording the condition of the book: New; Good; Fair; Poor; Bad. The American Revolution Reader Creative Commons Licensing This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. You are free: to Share—to copy, distribute, and transmit the work to Remix—to adapt the work Under the following conditions: Attribution—You must attribute the work in the following manner: This work is based on an original work of the Core Knowledge® Foundation (www.coreknowledge.org) made available through licensing under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License. This does not in any way imply that the Core Knowledge Foundation endorses this work. Noncommercial—You may not use this work for commercial purposes. Share Alike—If you alter, transform, or build upon this work, you may distribute the resulting work only under the same or similar license to this one. With the understanding that: For any reuse or distribution, you must make clear to others the license terms of this work. -

The Rights of the Colonists

@ib &out0 Pleafietp, No. 173. The kights of the Colonists BY SAMUELADAMS. REPORT OF THE COMMITTEE OF CORRESPONDENCE TO THE BOSTON TOWN MEETING, NOV. 20, 1772. I. Natural Rights of the Colonists as Men. Among the natural rights of the Colonists are these: First, a right to life; Secondly, to liberty; Thirdly, to property; together with the right to support and defend them in the best manner they can. These are evident branches of, rather than deduc- tions from, the duty of self-preservation, commonly called the first law of natur All men have $right to remain in a state of nature as long as they please; and in case of intolerable oppression, civil or re- ligious, to leave ,the society they belong to, and enter into another. When men enter into society, it is by voluntary consent; and they have a right to demand and insist upon the performance of such conditions and previous limitations as form an equitable original compact. Every natural right not expressly given up, or, from the nat- ure of a social compact, necessarily ceded, remains. All positive and civil laws should conform, as far as possible, to the law of natural reason and equity. As neither reason requires nor religion permits the contrary, every man living in or out of a state of civil society has a right peaceably and quietly to worship God according to the dictates of his conscience. "Just and true liberty, equal and impartial liberty," in mat- ters spiritual and temporal, is a thing that all men are clearly entitled to by the eternal and immutable laws of God and nat- 417 ure, as well as by the law of nations and all well-grounded mu- nicipal laws, which must have their foundation in the former. -

Riot, Sedition, and Insurrection: Media and the Road to the American Revolution

Pequot Library Riot, Sedition, and Insurrection: Media and The Road to the American Revolution Educator Guide School Programs 2-2-2020 Table of Contents Introduction ............................................................................................................................................. 2 Discussion Questions: .............................................................................................................................. 3 Vocabulary ............................................................................................................................................... 4 Pamphlet Culture and the American Revolution ......................................................................................... 6 Background Information........................................................................................................................... 7 Causes and Events ............................................................................................................................... 7 Intellectual Culture .............................................................................................................................. 9 Influences on Revolutionary Era Political Thought................................................................................ 9 Internet Resources .................................................................................................................................. 14 Activities for School Groups ..................................................................................................................