The Rights of the Colonists

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews the Public Historian, Vol

Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The Public Historian, Vol. 25, No. 2 (Spring 2003), pp. 80-87 Published by: University of California Press on behalf of the National Council on Public History Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/10.1525/tph.2003.25.2.80 . Accessed: 23/02/2012 10:14 Your use of the JSTOR archive indicates your acceptance of the Terms & Conditions of Use, available at . http://www.jstor.org/page/info/about/policies/terms.jsp JSTOR is a not-for-profit service that helps scholars, researchers, and students discover, use, and build upon a wide range of content in a trusted digital archive. We use information technology and tools to increase productivity and facilitate new forms of scholarship. For more information about JSTOR, please contact [email protected]. University of California Press and National Council on Public History are collaborating with JSTOR to digitize, preserve and extend access to The Public Historian. http://www.jstor.org 80 n THE PUBLIC HISTORIAN Boston Museum and Exhibit Reviews The American public increasingly receives its history from images. Thus it is incumbent upon public historians to understand the strategies by which images and artifacts convey history in exhibits and to encourage a conver- sation about language and methodology among the diverse cultural work- ers who create, use, and review these productions. The purpose of The Public Historian’s exhibit review section is to discuss issues of historical exposition, presentation, and understanding through exhibits mounted in the United States and abroad. Our aim is to provide an ongoing assess- ment of the public’s interest in history while examining exhibits designed to influence or deepen their understanding. -

A Case Study of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson

University of Tennessee, Knoxville TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange Supervised Undergraduate Student Research Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects and Creative Work Spring 5-2007 Reputation in Revolutionary America: A Case Study of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson Elizabeth Claire Anderson University of Tennessee - Knoxville Follow this and additional works at: https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj Recommended Citation Anderson, Elizabeth Claire, "Reputation in Revolutionary America: A Case Study of Samuel Adams and Thomas Hutchinson" (2007). Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects. https://trace.tennessee.edu/utk_chanhonoproj/1040 This is brought to you for free and open access by the Supervised Undergraduate Student Research and Creative Work at TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. It has been accepted for inclusion in Chancellor’s Honors Program Projects by an authorized administrator of TRACE: Tennessee Research and Creative Exchange. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Elizabeth Claire Anderson Bachelor of Arts 9lepu.tation in ~ Unwtica: a ~e studq- oj Samuel a.dartt;., and g fuun.a:, !JtulcIiUu,on 9JetIi~on !lWWuj ~ g~i6, Sp~ 2007 In July 1774, having left British America after serving terms as Lieutenant- Governor and Governor of Massachusetts, Thomas Hutchinson met with King George III. During the conversation they discussed the treatment Hutchinson received in America: K. In such abuse, Mf H., as you met with, I suppose there must have been personal malevolence as well as party rage? H. It has been my good fortune, Sir, to escape any charge against me in my private character. The attacks have been upon my publick conduct, and for such things as my duty to your Majesty required me to do, and which you have been pleased to approve of. -

Samuel Adams

Monumental Milestones Milestones Monumental The Life and of Times samuel adams samuel adams Karen Bush Gibson The Life and Times of samuel Movement Rights Civil The adams Karen Bush Gibson As America’s first politician, Samuel Adams dedicated his life to improving the lives of the colonists. At a young age, he began talking and listening to people to find out what issues mattered the most. Adams proposed new ideas, first in his own newspaper, then in other newspapers throughout the colonies. When Britain began taxing the colonies, Adams encouraged boy- cotting and peaceful protests. He was an organizer of the Boston Tea Party, one of the main events leading up to the American Revolution. The British seemed intent on imprisoning Adams to keep him from speaking out, but he refused to stop. He was one of the first people to publicly declare that the colonies should be independent, and he worked tirelessly to see that they gained that independence. According to Thomas Jefferson, Samuel Adams was the Father of the Revolution. ISBN 1-58415-440-3 90000 9 PUBLISHERS 781584 154402 samueladamscover.indd 1 5/3/06 12:51:01 PM Copyright © 2007 by Mitchell Lane Publishers, Inc. All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced without written permission from the publisher. Printed and bound in the United States of America. Printing 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Gibson, Karen Bush. The life and times of Samuel Adams/Karen Bush Gibson. p. cm. — (Profiles in American history) Includes bibliographical references and index. -

Thomas Hutchinson: Traitor to Freedom?

Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History Volume 2 Issue 1 Article 3 June 2018 Thomas Hutchinson: Traitor to Freedom? Kandy A. Crosby-Hastings Liberty University, [email protected] Follow this and additional works at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ljh Part of the United States History Commons Recommended Citation Crosby-Hastings, Kandy A. (2018) "Thomas Hutchinson: Traitor to Freedom?," Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History: Vol. 2 : Iss. 1 , Article 3. Available at: https://digitalcommons.liberty.edu/ljh/vol2/iss1/3 This Article is brought to you for free and open access by Scholars Crossing. It has been accepted for inclusion in Bound Away: The Liberty Journal of History by an authorized editor of Scholars Crossing. For more information, please contact [email protected]. Thomas Hutchinson: Traitor to Freedom? Abstract Thomas Hutchinson is perhaps one of the most controversial figures of the American Revolution. His Loyalist bent during a time when patriotism and devotion to the American cause was rampant and respected led to his being the target of raids and protests. His actions, particularly his correspondence to Britain regarding the political actions of Bostonians, caused many to question his motives and his allegiance. The following paper will examine Thomas Hutchinson’s Loyalist beliefs, where they originated, and how they affected his political and everyday life. It will examine Thomas Hutchinson’s role during America’s bid for freedom from the Mother Country. Keywords Thomas Hutchinson, Loyalism, the American Revolution Cover Page Footnote I would like to thank my family for supporting me in my writing endeavors. I would also like to thank Dr. -

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution

Construction of the Massachusetts Constitution ROBERT J. TAYLOR J. HI s YEAR marks tbe 200tb anniversary of tbe Massacbu- setts Constitution, the oldest written organic law still in oper- ation anywhere in the world; and, despite its 113 amendments, its basic structure is largely intact. The constitution of the Commonwealth is, of course, more tban just long-lived. It in- fluenced the efforts at constitution-making of otber states, usu- ally on their second try, and it contributed to tbe shaping of tbe United States Constitution. Tbe Massachusetts experience was important in two major respects. It was decided tbat an organic law should have tbe approval of two-tbirds of tbe state's free male inbabitants twenty-one years old and older; and tbat it sbould be drafted by a convention specially called and chosen for tbat sole purpose. To use the words of a scholar as far back as 1914, Massachusetts gave us 'the fully developed convention.'^ Some of tbe provisions of the resulting constitu- tion were original, but tbe framers borrowed heavily as well. Altbough a number of historians have written at length about this constitution, notably Prof. Samuel Eliot Morison in sev- eral essays, none bas discussed its construction in detail.^ This paper in a slightly different form was read at the annual meeting of the American Antiquarian Society on October IS, 1980. ' Andrew C. McLaughlin, 'American History and American Democracy,' American Historical Review 20(January 1915):26*-65. 2 'The Struggle over the Adoption of the Constitution of Massachusetts, 1780," Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society 50 ( 1916-17 ) : 353-4 W; A History of the Constitution of Massachusetts (Boston, 1917); 'The Formation of the Massachusetts Constitution,' Massachusetts Law Quarterly 40(December 1955):1-17. -

Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750Th Anniversary William F

College of William & Mary Law School William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository Faculty Publications Faculty and Deans 1976 Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary William F. Swindler William & Mary Law School Repository Citation Swindler, William F., "Runnymede Revisited: Bicentennial Reflections on a 750th Anniversary" (1976). Faculty Publications. 1595. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs/1595 Copyright c 1976 by the authors. This article is brought to you by the William & Mary Law School Scholarship Repository. https://scholarship.law.wm.edu/facpubs MISSOURI LAW REVIEW Volume 41 Spring 1976 Number 2 RUNNYMEDE REVISITED: BICENTENNIAL REFLECTIONS ON A 750TH ANNIVERSARY* WILLIAM F. SWINDLER" I. MAGNA CARTA, 1215-1225 America's bicentennial coincides with the 750th anniversary of the definitive reissue of the Great Charter of English liberties in 1225. Mile- stone dates tend to become public events in themselves, marking the be- ginning of an epoch without reference to subsequent dates which fre- quently are more significant. Thus, ten years ago, the common law world was astir with commemorative festivities concerning the execution of the forced agreement between King John and the English rebels, in a marshy meadow between Staines and Windsor on June 15, 1215. Yet, within a few months, John was dead, and the first reissues of his Charter, in 1216 and 1217, made progressively more significant changes in the document, and ten years later the definitive reissue was still further altered.' The date 1225, rather than 1215, thus has a proper claim on the his- tory of western constitutional thought-although it is safe to assume that few, if any, observances were held vis-a-vis this more significant anniver- sary of Magna Carta. -

John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: a Reappraisal.”

The Historical Journal of Massachusetts “John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal.” Author: Arthur Scherr Source: Historical Journal of Massachusetts, Volume 46, No. 1, Winter 2018, pp. 114-159. Published by: Institute for Massachusetts Studies and Westfield State University You may use content in this archive for your personal, non-commercial use. Please contact the Historical Journal of Massachusetts regarding any further use of this work: [email protected] Funding for digitization of issues was provided through a generous grant from MassHumanities. Some digitized versions of the articles have been reformatted from their original, published appearance. When citing, please give the original print source (volume/number/date) but add "retrieved from HJM's online archive at http://www.westfield.ma.edu/historical-journal/. 114 Historical Journal of Massachusetts • Winter 2018 John Adams Portrait by Gilbert Stuart, c. 1815 115 John Adams, Political Moderation, and the 1820 Massachusetts Constitutional Convention: A Reappraisal ARTHUR SCHERR Editor's Introduction: The history of religious freedom in Massachusetts is long and contentious. In 1833, Massachusetts was the last state in the nation to “disestablish” taxation and state support for churches.1 What, if any, impact did John Adams have on this process of liberalization? What were Adams’ views on religious freedom and how did they change over time? In this intriguing article Dr. Arthur Scherr traces the evolution, or lack thereof, in Adams’ views on religious freedom from the writing of the original 1780 Massachusetts Constitution to its revision in 1820. He carefully examines contradictory primary and secondary sources and seeks to set the record straight, arguing that there are many unsupported myths and misconceptions about Adams’ role at the 1820 convention. -

Sons of Liberty Patriots Or Terrorists

The Sons of Liberty : Patriots? OR Common ? Core Terrorists focused! http://www.teacherspayteachers.com/Store/Mr-Educator-A-Social-Studies-Professional Instructions: 1.) This activity can be implemented in a variety of ways. I have done this as a class debate and it works very, very well. However, I mostly complete this activity as three separate nightly homework assignments, or as three in-class assignments, followed by an in-class Socratic Seminar. The only reason I do this is because I will do the Patriots v. Loyalists: A Common Core Class Debate (located here: http://www.teacherspayteachers.com/ Product/Patriots-vs-Loyalists-A-Common-Core-Class-Debate-874989) and I don’t want to do two debates back-to-back. 2.) Students should already be familiar with the Sons of Liberty. If they aren’t, you may need to establish the background knowledge of what this group is and all about. 3.) I will discuss the questions as a class that are on the first page of the “Day 1” reading. Have classes discuss what makes someone a patriot and a terrorist. Talk about how they define these words? Can one be one without being the other? How? Talk about what both sides are after. What are the goals of terrorists? Why are they doing it? It is also helpful to bring in some outside quotes of notorious terrorists, such as Bin Laden, to show that they are too fighting for what they believe to be a just, noble cause. 4.) For homework - or as an in-class activity - assign the Day 1 reading. -

Amicus Brief

No. 20-855 ================================================================================================================ In The Supreme Court of the United States --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- MARYLAND SHALL ISSUE, INC., et al., Petitioners, v. LAWRENCE HOGAN, IN HIS CAPACITY OF GOVERNOR OF MARYLAND, Respondent. --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- On Petition For A Writ Of Certiorari To The United States Court Of Appeals For The Fourth Circuit --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- BRIEF OF AMICUS CURIAE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION IN SUPPORT OF PETITIONERS --------------------------------- ♦ --------------------------------- JOSEPH G.S. GREENLEE FIREARMS POLICY COALITION 1215 K Street, 17th Floor Sacramento, CA 95814 (916) 378-5785 [email protected] January 28, 2021 Counsel of Record ================================================================================================================ COCKLE LEGAL BRIEFS (800) 225-6964 WWW.COCKLELEGALBRIEFS.COM i TABLE OF CONTENTS Page TABLE OF CONTENTS ........................................ i INTEREST OF THE AMICUS CURIAE ............... 1 SUMMARY OF ARGUMENT ................................ 1 ARGUMENT ........................................................... 3 I. Personal property is entitled to full consti- tutional protection ....................................... 3 II. Since medieval England, the right to prop- erty—both personal and real—has been protected against arbitrary seizure -

Metropolitan Boston Downtown Boston

WELCOME TO MASSACHUSETTS! CONTACT INFORMATION REGIONAL TOURISM COUNCILS STATE ROAD LAWS NONRESIDENT PRIVILEGES Massachusetts grants the same privileges EMERGENCY ASSISTANCE Fire, Police, Ambulance: 911 16 to nonresidents as to Massachusetts residents. On behalf of the Commonwealth, MBTA PUBLIC TRANSPORTATION 2 welcome to Massachusetts. In our MASSACHUSETTS DEPARTMENT OF TRANSPORTATION 10 SPEED LAW Observe posted speed limits. The runs daily service on buses, trains, trolleys and ferries 14 3 great state, you can enjoy the rolling Official Transportation Map 15 HAZARDOUS CARGO All hazardous cargo (HC) and cargo tankers General Information throughout Boston and surrounding towns. Stations can be identified 13 hills of the west and in under three by a black on a white, circular sign. Pay your fare with a 9 1 are prohibited from the Boston Tunnels. hours travel east to visit our pristine MassDOT Headquarters 857-368-4636 11 reusable, rechargeable CharlieCard (plastic) or CharlieTicket 12 DRUNK DRIVING LAWS Massachusetts enforces these laws rigorously. beaches. You will find a state full (toll free) 877-623-6846 (paper) that can be purchased at over 500 fare-vending machines 1. Greater Boston 9. MetroWest 4 MOBILE ELECTRONIC DEVICE LAWS Operators cannot use any of history and rich in diversity that (TTY) 857-368-0655 located at all subway stations and Logan airport terminals. At street- 2. North of Boston 10. Johnny Appleseed Trail 5 3. Greater Merrimack Valley 11. Central Massachusetts mobile electronic device to write, send, or read an electronic opens its doors to millions of visitors www.mass.gov/massdot level stations and local bus stops you pay on board. -

Thomas Jefferson and John Adams in the Newberry Collection

QUICK GUIDE Thomas Jefferson and John Adams in the Newberry Collection How to Use Our Collection At the Newberry, an independent research library, readers do not borrow books to take home, but consult rare books, manuscripts, and other materials here. We welcome researchers who are at least 14 years old or in the ninth grade. Visit https://requests.newberry.org to create a reader account and start exploring our collection. When you arrive at the Newberry for research, a free reader card will be issued to you in the Welcome Center on the first floor. Find further information about our collection and public programs at www.newberry.org. Questions? Contact the reference desk at (312) 255-3506 or [email protected]. Manuscripts and Correspondence of Adams and Jefferson Herbert R. Strauss Collection of Adams Family Letters, manuscript Jefferson provides advice to William 1763-1829. Includes 17 letters written by John Short, his private secretary in Paris, for Short’s Adams, Abigail Adams, John Quincy Adams, and travels in Italy. He also requests favors from Short, Samuel Adams; recipients include James Madison including the purchase of books, wine, and a pasta- and Dr. Benjamin Rush. Call # Vault Case MS 6A 81 maker. Call # Vault Mi Adams, John. Letter to John Jay, December 19, 1800. The Papers of John Adams. Cambridge, MA: Belknap Upon the resignation of Oliver Ellsworth from the Press of Harvard University Press, 1977-<2016>. The office of Chief Justice of the Supreme Court, series “General Correspondence and Other Papers of President Adams sent this letter to Jay advising him the Adams Statesmen,” in 19 volumes to date, cover of his renomination to that office. -

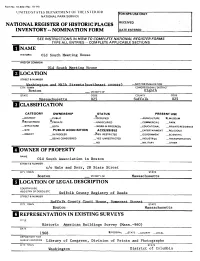

Hclassifi Cation

Form No 10-300 (Rev 10-74) UNITED STATES DEPARTMENT OF THE INTERIOR FOR NPS USE GNtY NATIONAL PARK SERVICE NATIONAL REGISTER OF HISTORIC PLACES RECEIVE!} INVENTORY -- NOMINATION FORM DATE ENTERED SEE INSTRUCTIONS IN HOW TO COMPLETE NATIONAL REGISTER FORMS ____________TYPE ALL ENTRIES - COMPLETE APPLICABLE SECTIONS______ | NAME HISTORIC old South Meeting House AND/OR COMMON Old South Meeting House Q LOCATION STREETS NUMBER Washington and Milk Streets ("northeast corner) _ NOT FOR PUBLICATION CITY. TOWN CONGRESSIONAL DISTRICT Boston _ VICINITY OF Eighth STATE CODE COUNTY CODE Massachusetts 025 Suffolk 025 HCLASSIFI CATION CATEGORY OWNERSHIP STATUS PRESENT USE _DISTRICT _PUBLIC —OCCUPIED —AGRICULTURE X-MUSEUM ^BUILDING(S) ^PRIVATE —UNOCCUPIED —COMMERCIAL —PARK —STRUCTURE _BOTH —WORK IN PROGRESS —EDUCATIONAL —PRIVATE RESIDENCE —SITE PUBLIC ACQUISITION ACCESSIBLE —ENTERTAINMENT —RELIGIOUS —OBJECT —IN PROCESS -2VES: RESTRICTED —GOVERNMENT —SCIENTIFIC —BEING CONSIDERED —YES: UNRESTRICTED — INDUSTRIAL _ TRANSPORTATION —NO —MILITARY —OTHER OWNER OF PROPERTY NAME Old South Association in Boston STREETS NUMBER c/o Hale and Dorr, 28 State Street CITY. TOWN STATE Boston VICINITY OF Massachusetts LOCATION OF LEGAL DESCRIPTION COURTHOUSE, REGISTRY OF DEEDS,ETC Suffolk County Registry of Deeds STREETS NUMBER Suffolk County Court House Somprspt Strppt CITY, TOWN STATE Boston Massachusetts REPRESENTATION IN EXISTING SURVEYS Historic American Buildings Survey (Mass.-960) DATE 1968 X-FEDERAL —STATE —COUNTY —LOCAL DEPOSITORY FOR SURVEY RECORDS Library of Congress, Division of Prints and Photographs CITY, TOWN STATE W&shington District of Columbia DESCRIPTION CONDITION CHECK ONE CHECK ONE ^EXCELLENT —DETERIORATED _UNALTERED ^.ORIGINAL SITE _GOOD _RUINS _XALTERED _MOVED DATE_____ _FAIR _UNEXPOSED DESCRIBE THE PRESENT AND ORIGINAL (IF KNOWN) PHYSICAL APPEARANCE Old South Meeting House, located at the northeast corner of Washington and Milk Streets in downtown Boston, was built as the second home of the Third Church in Boston, gathered in 1669.