Calonectris Diomedea) Studied by Means of a Direction Recorder

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

BARC SUBMISSION Cory's Shearwater Calonectris Borealis

BARC SUBMISSION Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis – Bremer Canyon ‘hotspot’, Western Australia, 5th January 2020 Machi Yoshida (prepared by Daniel Mantle & Plaxy Barratt) Submission note: we believe this sighting constitutes the 3rd time that one or more Cory’s Shearwater have been sighted in Australia (after a bird seen off Bremer Bay on the 19th January 2019 and up to four birds off Denmark, Western Australia six days prior to this record). Taxonomic notes: Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris borealis is a relatively recent split from Scopoli’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea as accepted by the IOC (version 9.2; following Robb & Mullarney 2008, Howell 2012, and Sangster et al. 2012) and the HBW-Birdlife list of birds (version 3.0). However, other taxonomies such as Clements (2019) still consider these two taxa as subspecies (C. d. borealis and C. d. diomedea, respectively). All three of these major taxonomies accept Cape Verde Shearwater Calonectris edwardsii as a distinct species. Circumstances of sighting: a single Cory’s Shearwater was observed and photographed by Machi Yoshida at the Orca ‘hotspot’ at the head of the Bremer Canyon (near the shelf edge), Western Australia on the 5th January, 2020. This sighting was considerably more distant than the birds seen off Denmark six days previously by Machi and Billy Thom. Description (from photo): • A large shearwater with a thick, yellow bill, pale whitish underparts and dull beige to brown upperparts. • The yellow bill is notably robust, bright yellow, and with a darker tip (the fine detail is not apparent, but presumed to be a dark subterminal band rather than full dark tip). -

The Taxonomy of the Procellariiformes Has Been Proposed from Various Approaches

山 階 鳥 研 報(J. Yamashina Inst. Ornithol.),22:114-23,1990 Genetic Divergence and Relationships in Fifteen Species of Procellariiformes Nagahisa Kuroda*, Ryozo Kakizawa* and Masayoshi Watada** Abstract The genetic analysis of 23 protein loci in 15 species of Procellariiformes was made The genetic distancesbetween the specieswas calculatedand a dendrogram was formulated of the group. The separation of Hydrobatidae from all other taxa including Diomedeidae agrees with other precedent works. The resultsof the present study support the basic Procellariidclassification system. However, two points stillneed further study. The firstpoint is that Fulmarus diverged earlier from the Procellariidsthan did the Diomedeidae. The second point is the position of Puffinuspacificus which appears more closely related to the Pterodroma petrels than to other Puffinus species. These points are discussed. Introduction The taxonomy of the Procellariiformes has been proposed from various approaches. The earliest study by Forbes (1882) was made by appendicular myology. Godman (1906) and Loomis (1918) studied this group from a morphological point of view. The taxonomy of the Procellariiformes by functional osteology and appendicular myology was studied by Kuroda (1954, 1983) and Klemm (1969), The results of the various studies agreed in proposing four families of Procellariiformes: Diomedeidae, Procellariidae, Hydrobatidae, and Pelecanoididae. They also pointed out that the Procellariidae was a heterogenous group among them. Timmermann (1958) found the parallel evolution of mallophaga and their hosts in Procellariiformes. Recently, electrophoretical studies have been made on the Procellariiformes. Harper (1978) found different patterns of the electromorph among the families. Bar- rowclough et al. (1981) studied genetic differentiation among 12 species of Procellari- iformes at 16 loci, and discussed the genetic distances among the taxa but with no consideration of their phylogenetic relationships. -

FEEDING ECOLOGY of the CAPE VERDEAN SHEARWATER (Calonectris Edwardsii) POPULATION of RASO ISLET, CAPE VERDE (P1-B-11)

2nd World Seabird Conference “Seabirds: Global Ocean Sentinels” 26-30 October 2015 Cape Town, South Africa FEEDING ECOLOGY OF THE CAPE VERDEAN SHEARWATER (Calonectris edwardsii) POPULATION OF RASO ISLET, CAPE VERDE (P1-B-11) Isabel Rodrigues1,3; Nuno Oliveira 2 Rui Freitas 3 Tommy Melo1 Pedro Geraldes 2 1Biosfera I, Cabo Verde, www.biosfera1.com; 2SPEA, Portugal, www.spea.pt, 3 Universidade de Cabo Verde, www.unicv.edu.cv Raso Islet with only 5.76 km2, is an area of great importance to Cape Verdean Shearwaters as we find one of the largest colonies of the species there. The great biological value of this islet is even more remarkable for hosting very large populations of other species, such as the Brown Booby, Red-billed Tropicalbird and even the endemic Raso Lark, among others. Along with Branco Islet, also included in the Nature Reserve, both populations constitute about 75% of the nesting population of the Cape Verde islands (Fig. 1). The Cape Verde Shearwater (Procellariiformes, Procellariidae) (Fig. 2) is an endemic species of Cape Verde and has recently been separated from Calonectris diomedea species, due to their morphological and genetic differences, and pelagic habits; feeding mostly on the open sea (Hazevoet 1995). METHODOLOGY RESULTS The samples were collected between 14 October and 12 November, in two In total, 80 regurgitations from juvenile Cape Verde Shearwaters were collected; consecutive years, 2012 and 2013. We randomly obtained 80 samples of juvenile including 50 individuals sampled in 2012, and 30 individuals in 2013. regurgitation. Each juvenile was sampled only once. During or after handling, Based on knowledge of local fish populations and according to the current juveniles tend to regurgitate stomach contents without the need to resort to the description, the identified prey of Cape Verde shearwaters belonged to 5 species induced regurgitation method. -

What Is the Importance of Islands to Environmental Conservation?

Environmental Conservation (2017) 44 (4): 311–322 C Foundation for Environmental Conservation 2017 doi:10.1017/S0376892917000479 What is the importance of islands to environmental THEMATIC SECTION Humans and Island conservation? Environments CHRISTOPH KUEFFER∗ 1 AND KEALOHANUIOPUNA KINNEY2 1Institute of Integrative Biology, ETH Zurich, Universitätsstrasse 16, CH-8092 Zurich, Switzerland and 2Institute of Pacifc Islands Forestry, US Forest Service, 60 Nowelo St. Hilo, HI, USA Date submitted: 15 May 2017; Date accepted: 8 August 2017 SUMMARY islands of the world’s oceans, we cover both islands close to continents and others isolated far out in the oceans, and the This article discusses four features of islands that make full range from small to very large islands. Small and isolated them places of special importance to environmental islands represent unique cultural and biological values and the conservation. First, investment in island conservation environmental challenges of insularity in its most pronounced is both urgent and cost-effective. Islands are form. However, as we will demonstrate, all islands and island threatened hotspots of diversity that concentrate people share enough come concerns to consider them together unique cultural, biological and geophysical values, (Baldacchino 2007; Royle 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; and they form the basis of the livelihoods of Baldacchino & Niles 2011; Royle 2014). millions of islanders. Second, islands are paradigmatic Islands are hotspots of cultural, biological and geophysical places of human–environment relationships. Island diversity, and as such they form the basis of the livelihoods livelihoods have a long tradition of existing within of millions of islanders (Menard 1986; Nunn 1994; Royle spatial, ecological and ultimately social boundaries 2008; Gillespie & Clague 2009; Royle 2014; Kueffer et al. -

First Two Cases of Melanism in Cory's Shearwater Calonectris Diomedea

Bried et al.: Melanism in Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea 19 FIRST TWO CASES OF MELANISM IN CORY’S SHEARWATER CALONECTRIS DIOMEDEA JOËL BRIED1, HELDER FRAGA2, PASCUAL CALABUIG-MIRANDA3 & VERÓNICA C. NEVES4 1 Departamento de Oceanografia e Pescas, Centro do IMAR da Universidade dos Açores, 9901-862 Horta, Açores, Portugal ([email protected], [email protected]) 2 Secretaria Regional do Ambiente, Rua Cônsul Dabney, 9900-014 Horta, Açores, Portugal 3 Centro de Recuperación de Fauna Silvestre de Tafira, Cabildo de Gran Canaria, Spain 4 Ornithology Unit, IBLS, University of Glasgow, Graham Kerr Building, G12 8QQ, Glasgow, Scotland, UK Received 19 November 2004, accepted 8 April 2005 SUMMARY BRIED, J., FRAGA, H., CALABUIG-MIRANDA, P. & NEVES, V.C. 2005. First two cases of melanism in Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea. Marine Ornithology 33: 19-22. Although aberrant colourations occur in a great variety of animal species, their frequency of occurrence is low. Here, we report the first two observations of melanistic Cory’s Shearwaters Calonectris diomedea, in the Azores archipelago and on the Canary Islands. Because dark plumages may be associated with subordinate status within petrel flocks and with increased conspicuousness, melanistic individuals would have increased difficulties in obtaining food compared with their normally coloured conspecifics. This phenomenon might explain why melanism seems to occur less frequently than other aberrant colour patterns in this group. Key words: Melanism, Cory’s Shearwater, Calonectris diomedea, Procellariiformes INTRODUCTION individuals were found in 2003. The first individual was found near a pier at San Andrés on 30 October. The second observation Aberrant colourations have a low frequency of occurrence in occurred in a street of Horta on 21 November. -

A Sight Record of a Streaked Shearwater in Oregon

NOTES A SIGHT RECORD OF A STREAKED SHEARWATER IN OREGON MICHAEL P. FORCE, 2304 PrinceAlbert Street,Vancouver, B.C., CanadaV5T 3W5 RICHARD A. ROWLETT, P.O. Box 7386, Bellevue,Washington, USA 98008-1386 GEOFF GRACE, 3436 CanberraStreet, SilverSpring, Maryland,USA 20904 On 13 September 1996, while conductingsurveys for marine mammalsand seabirdsaboard the NOAA ship McArthur about 57 kilometersoff the southern Oregon coast,we founda StreakedShearwater (Calonectris leucomelas), a species familiar to both Force and Rowlett. The bird was seen at 08:40 in a large mixed feedingflock over Heceta Bank. Lane County,Oregon (43 ø 59.1 • N, 124 ø 51.4 fW). This constitutesthe firstrecord of the StreakedShearwater for Oregonand the most northeasterlyPacific Ocean occurrence. We hadunobstructed views from the ship'sflying bridge, 14 metersabove sea level. The birdwas seen clearly for abouttwo minutesand passed in frontof the shipas close as 250 meters.It patrolledlow over the water on the starboardside, passed in front of the ship, and eventuallydisappeared astern. We had a variety of binoculars available:20 x 60 prism-stabilizedZeiss (Force), 25 x 150 ship-mountedFujinons (Rowlett),and 7 x 50 hand-heldFujinons (Grace). The ship was engagedin a line- transectsurvey of marine mammalswhose protocol prevented further investigation. We preparedfield notes immediatelyafter the bird was lost from view and before consultingany references.A written report is on file with the Oregon Bird Records Committee. General Appearance:The bird appearedto be in freshplumage with no signof molt, suggestingthat it may have beenin its firstyear. Fairly large and long-winged, gleamingwhite below and brown abovewith a strikingwhite head when seenat a distance.Pale-tipped back feathersgave it a saddledappearance. -

Notes on Tubinares, Including Records Which Affect the A

58 MURrH¾,Notes on Tubinares. Jan.Auk NOTES ON TUBINARES, INCLUDING RECORDS WHICH AFFECT THE A. O. U. CHECK-LIST. BY ROBERT CUSHMAN MURPHY. 1. Thala.•.•arehe ehlororhyneho.• (Gmelin).YELLOW-NOSED •OLLYMAWK. The first North American record of this subantarctic albatross is basedupon a skinin the AmericanMuseum of Natural History (collectionof Dr. L. C. Sanford,No. 9835,). The specimenis an adult of unknown sex. It was collected near Seal Island, off MacbiasBay, Maine, on August1, 1913,by Mr. ErnestO. Joye, subsequentlycoming into the possessionof Mr. Allen L. Moses and, finally, that of Dr. Sanford. Seal Island is Canadianterri- tory, and sincethe localityin whichthe birdwas killed is on the internationalborder, south of Grand Manan, the recordconstitutes an addition to the local avifauna of both New Brunswick and Maine. The specimenclosely resembles others collected by the writer in the South Atlantic Ocean. The fact that its sex was not determined decreases the value of measurements, which are, however,as follows: Wing 482; tail 186; culmen 116; tarsus 78; middle toe with claw 114 min. Thalassarchechlororhynchos is of circumpolardistribution in the southern hemisphere. Its Atlantic breeding grounds are presumablyin the "Tristan da Cunha Subarea,"as recently definedin Dr. RobertoDabbene's admirable paper on the petrels and albatrosses of the South Atlantic. • Sufficient material is not available for a determinationof the subspeclficstatus of the Atlantic bird, or of its relationshipwith the "Thalassogeronexi- mius" of Verrill. 2. Calonectriskuhlii kuhlii (Bole). MEDITERRANEANSHEAR- WATER. While examiningseries of North Americanexamples of the large shearwaterdescribed by Cory as Puffinusborealis (Bull. Nuttall Orn. C1.Vol. 6, p: 84, 1881),the writerhas occasionally encountered • E1 Hornero, Vol. -

Scopoli's Shearwater Off Scilly

Scopoli’s Shearwater off Scilly: new to Britain E. Ashley Fisher and Robert L. Flood Abstract A Cory’s Shearwater Calonectris diomedea of the nominate race diomedea, often referred to as ‘Scopoli’s Shearwater’, was seen and photographed from a boat approximately 10 km south of the Isles of Scilly on 2nd August 2004. This sighting constitutes the first accepted record of Scopoli’s Shearwater for Britain. Although there had been several previous claims of this distinctive race, they lacked sufficient supporting documentation and proved to be inconclusive. The sighting described here was brief and light conditions poor but a set of photographs proved the bird’s identity. Elimination of the much commoner Cory’s Shearwater C. d. borealis is discussed. The status of Scopoli’s Shearwater off Scilly is considered. n the evening of 2nd August 2004, feature that separates the nominate race C. d. along with two other birders, John diomedea (‘Scopoli’s Shearwater’) from the OHigginson and Bryan Thomas, we regularly occurring Cory’s C. d. borealis were on board MV Sapphire, approximately (Gutiérrez 1998). EAF momentarily thought 10 km south of the Isles of Scilly. At about he saw the Scopoli’s pattern. Although we 20.00 hrs, a large shearwater appeared from were concentrating on the underwing, we did the west, directly in line with the setting sun. register a relatively slim bill, head, body and It was initially called as a Great Shearwater wings; it is not surprising that the bird in sil- Puffinus gravis and then as a Cory’s Shear- houette was first called as a Great Shearwater. -

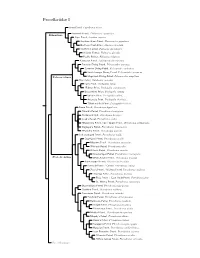

Procellariidae Species Tree

Procellariidae I Snow Petrel, Pagodroma nivea Antarctic Petrel, Thalassoica antarctica Fulmarinae Cape Petrel, Daption capense Southern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes giganteus Northern Giant-Petrel, Macronectes halli Southern Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialoides Atlantic Fulmar, Fulmarus glacialis Pacific Fulmar, Fulmarus rodgersii Kerguelen Petrel, Aphrodroma brevirostris Peruvian Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides garnotii Common Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides urinatrix South Georgia Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides georgicus Pelecanoidinae Magellanic Diving-Petrel, Pelecanoides magellani Blue Petrel, Halobaena caerulea Fairy Prion, Pachyptila turtur ?Fulmar Prion, Pachyptila crassirostris Broad-billed Prion, Pachyptila vittata Salvin’s Prion, Pachyptila salvini Antarctic Prion, Pachyptila desolata ?Slender-billed Prion, Pachyptila belcheri Bonin Petrel, Pterodroma hypoleuca ?Gould’s Petrel, Pterodroma leucoptera ?Collared Petrel, Pterodroma brevipes Cook’s Petrel, Pterodroma cookii ?Masatierra Petrel / De Filippi’s Petrel, Pterodroma defilippiana Stejneger’s Petrel, Pterodroma longirostris ?Pycroft’s Petrel, Pterodroma pycrofti Soft-plumaged Petrel, Pterodroma mollis Gray-faced Petrel, Pterodroma gouldi Magenta Petrel, Pterodroma magentae ?Phoenix Petrel, Pterodroma alba Atlantic Petrel, Pterodroma incerta Great-winged Petrel, Pterodroma macroptera Pterodrominae White-headed Petrel, Pterodroma lessonii Black-capped Petrel, Pterodroma hasitata Bermuda Petrel / Cahow, Pterodroma cahow Zino’s Petrel / Madeira Petrel, Pterodroma madeira Desertas Petrel, Pterodroma -

Shearwatersrefs V1.10.Pdf

Introduction I have endeavoured to keep typos, errors, omissions etc in this list to a minimum, however when you find more I would be grateful if you could mail the details during 2018 & 2019 to: [email protected]. Please note that this and other Reference Lists I have compiled are not exhaustive and are best employed in conjunction with other sources. Grateful thanks to Ashley Fisher (www.scillypelagics.com) for the cover images. All images © the photographer. Joe Hobbs Index The general order of species follows the International Ornithologists' Union World Bird List (Gill, F. & Donsker, D. (eds.) 2017. IOC World Bird List. Available from: http://www.worldbirdnames.org/ [version 7.3 accessed August 2017]). Version Version 1.10 (January 2018). Cover Main image: Great Shearwater. At sea 3’ SW of the Bishop Rock, Isles of Scilly. 8th August 2009. Picture by Ashley Fisher. Vignette: Sooty Shearwater. At sea off the Isles of Scilly. 14th August 2009. Picture by Ashley Fisher. Species Page No. Audubon's Shearwater [Puffinus lherminieri] 34 Balearic Shearwater [Puffinus mauretanicus] 28 Bannerman's Shearwater [Puffinus bannermani] 37 Barolo Shearwater [Puffinus baroli] 38 Black-vented Shearwater [Puffinus opisthomelas] 30 Boyd's Shearwater [Puffinus boydi] 38 Bryan's Shearwater [Puffinus bryani] 29 Buller's Shearwater [Ardenna bulleri] 15 Cape Verde Shearwater [Calonectris edwardsii] 12 Christmas Island Shearwater [Puffinus nativitatis] 23 Cory's Shearwater [Calonectris borealis] 9 Flesh-footed Shearwater [Ardenna carneipes] 21 Fluttering -

AC7 Inf 04 Agenda Item 14

AC7 Inf 04 Agenda Item 14 Seventh Meeting of the Advisory Committee La Rochelle, France, 6 - 10 May 2013 Update on the population status and distribution of Mediterranean shearwaters Carles Carboneras1, Mia Derhé 2 & Iván Ramírez 2 1 – Medmaravis 2 – BirdLife International SUMMARY Three shearwater species live in the Mediterranean Sea and are listed in ACAP (Puffinus mauretanicus), or have been proposed as potential candidate species (Calonectris diomedea, Puffinus yelkouan). This paper brings an update on their conservation status, based on two specific workshops, coordinated by BirdLife International Europe, that took place as a back-to-back meeting to the 13th Medmaravis pan-Mediterranean Symposium (2011). For Calonectris diomedea, the breeding population was estimated at 142,478– 222,886 pairs (427,000–669,000 individuals) and predicted to decline by c.2% over 3 generations. Importantly, it also identified a lack of data on monitoring and research. Until estimates of adult survival and breeding probabilities in key countries (Tunisia, Italy) become available, any global population trend estimate for the species will remain purely speculative. This workshop also identified Calonectris diomedea as a frequent victim of bycatch in Mediterranean waters, although information from several fleets is lacking. Following the mentioned workshops, the status of Puffinus yelkouan was upgraded from Near Threatened to Vulnerable on the IUCN 2012 Red List. Its global population was estimated at 15,337–30,519 pairs, or 46,000–92,000 individuals. If the decline would continue at the current rate, the global population would decrease by c.50% over 54 years (3 generations). The main drivers of population decline were bycatch mortality and predation by invasive predators. -

Petrel-Like Birds with a Peculiar Foot Morphology from the Oligocene of Germany and Belgium (Aves: Procellariiformes)

Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 22(3):667±676, September 2002 q 2002 by the Society of Vertebrate Paleontology PETREL-LIKE BIRDS WITH A PECULIAR FOOT MORPHOLOGY FROM THE OLIGOCENE OF GERMANY AND BELGIUM (AVES: PROCELLARIIFORMES) GERALD MAYR1, D. STEFAN PETERS1, and SIEGFRIED RIETSCHEL2 1Forschungsinstitut Senckenberg, Division of Ornithology, Senckenberganlage 25, D-60325 Frankfurt a.M., Germany, [email protected] 2Staatliches Museum fuÈr Naturkunde Karlsruhe, Erbprinzenstraûe 13, D-76133 Karlsruhe, Germany ABSTRACTÐNew specimens of procellariiform birds are described from the Oligocene of Germany and Belgium, including a virtually complete and extraordinarily well preserved articulated skeleton. These birds show a peculiar foot morphology which to a striking degree resembles that of the recent Polynesian Storm-petrel Nesofregetta fuliginosa (Oceanitinae, Hydrobatidae). The pedal phalanges are dorso-ventrally compressed and especially the proximal phalanx of the fourth toe is grotesquely widened. The Oligocene Procellariiformes trenchantly differ, however, from Nesofre- getta, the closely related genus Fregetta, and all other taxa of recent Hydrobatidae in the remainder of the skeleton. Possibly the feet served as a brake for rapid stops in order to catch prey, and we consider the similarities to Nesofregetta to be a striking example of convergence among birds. The specimens described in this study are referred to Diome- deoides brodkorbi, D. lipsiensis, and to Diomedeoides sp. The genus Frigidafons is a junior synonym of Diomedeoides, and Diomedeoides minimus is a junior synonym of Diomedeoides (5 ``Gaviota'') lipsiensis. An incomplete articulated specimen of Diomedeoides brodkorbi is of special taphonomic interest, since in the close vicinity of its left wing two fairly large shark teeth can be discerned which probably stuck in the soft tissues of the bird when it was embedded in the sediment.