Uva-DARE (Digital Academic Repository)

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Crossroads of Newand Ancient

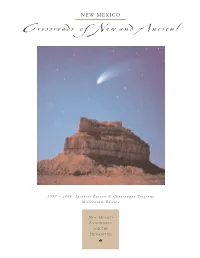

NEW MEXICO Crossroads of NewandAncient 1999 – 2000 Speakers Bureau & Chautauqua Programs Millennium Edition N EW M EXICO E NDOWMENT FOR THE H UMANITIES ABOUT THE COVER: AMATEUR PHOTOGRAPHER MARKO KECMAN of Aztec captures the crossroads of ancient and modern in New Mexico with this image of Comet Hale-Bopp over Fajada Butte in Chaco Culture National Historic Park. Kecman wanted to juxtapose the new comet with the butte that was an astronomical observatory in the years 900 – 1200 AD. Fajada (banded) Butte is home to the ancestral Puebloan sun shrine popularly known as “The Sun Dagger” site. The butte is closed to visitors to protect its fragile cultural sites. The clear skies over the Southwest led to discovery of Hale-Bopp on July 22-23, 1995. Alan Hale saw the comet from his driveway in Cloudcroft, New Mexico, and Thomas Bopp saw the comet from the desert near Stanfield, Arizona at about the same time. Marko Kecman: 115 N. Mesa Verde Ave., Aztec, NM, 87410, 505-334-2523 Alan Hale: Southwest Institute for Space Research, 15 E. Spur Rd., Cloudcroft, NM 88317, 505-687-2075 1999-2000 NEW MEXICO ENDOWMENT FOR THE HUMANITIES SPEAKERS BUREAU & CHAUTAUQUA PROGRAMS Welcome to the Millennium Edition of the New Mexico Endowment for the Humanities (NMEH) Resource Center Programming Guide. This 1999-2000 edition presents 52 New Mexicans who deliver fascinating programs on New Mexico, Southwest, national and international topics. Making their debuts on the state stage are 16 new “living history” Chautauqua characters, ranging from an 1840s mountain man to Martha Washington, from Governor Lew Wallace to Capitán Rafael Chacón, from Pat Garrett to Harry Houdini and Kit Carson to Mabel Dodge Luhan. -

Interview No. 282

University of Texas at El Paso ScholarWorks@UTEP Combined Interviews Institute of Oral History 12-1976 Interview no. 282 George E. Barnhart Follow this and additional works at: https://scholarworks.utep.edu/interviews Part of the Oral History Commons, and the Social and Behavioral Sciences Commons Recommended Citation Interview with George E. Barnhart by Carlos Tapia, 1976, "Interview no. 282," Institute of Oral History, University of Texas at El Paso. This Article is brought to you for free and open access by the Institute of Oral History at ScholarWorks@UTEP. It has been accepted for inclusion in Combined Interviews by an authorized administrator of ScholarWorks@UTEP. For more information, please contact [email protected]. UNIVERSITYOFTEXAS AT EL PASC INSTITUTEOFOR.AL HISTORY II.ITERVIEIdEE: GeorqeE. Barnhart INTERVIEI.IER: CarlosTaPia PROJECT: Class proiect DATEOF II'ITERVIEI'I: DecemberI 976 TERI''6OF USE: Unrestricted TAPENO.: 282 T:IAI'ISCRIPTI.iO.: 282 TRAIISCRISER: DATETRA|'ISCRIBED: BIOGRAPHICALSYiiOPSIS OF INTERVIEI'IEE: 01d-time E] Pasoresident. SUI{I}trRYOF I|'ITER\IIEI,I: j I ett and BioqraPhy;the MexicanRevol ution; Prohbi tion ; J'imGi JudgeRoy Bean' John|.lesleY Hardin; tf," O.pt.ssion; Worldl'lar II; 50 minutes I4 pages 'interview { Oral History with Mr- GeorgeE. Barnhart, interviewedby Carlos Tapia in December1976" ) T: Mr. Barnhar{wherewere you born and when? B: hlestBends, Okl ahoma. T: Whatwas the date? B: We]l, it's supposedto be February24, 1896. Theydidn't keepany records back in themdays. I had to checkback and I got two or three different [dates, but] that's the one I usedto look for a job. -

Tours & Treks Summit

2019 Tours & Treks Summit Meet the Team Michael Vincent – Tour Director Alaine Hope – Assistant Tour Coordinator Kelsey Voskamp – Reservations Coordinator Kevin Snow – Historian & Primary Expert Tour Guide Meet the Team Dr. Tom Noel – State Historian Chair & Expert Tour Guide Dr. Andrew Gulliford– Expert Tour Guide History Colorado Volunteers – Judy, Jean, Ellen and Barb. Membership ↘ Membership is here tonight or available via phone at 303-866-3639 ↘ Chat with them if you need to renew or become a member of History Colorado ↘ They can answer any questions about your membership ↘ Only History Colorado members can register for Tours & Treks before January 2019 From the Monte Vista Crane Festival to hikes with state archaeologists, Tours and Treks is supported by you. History Colorado members and donors fund hundreds of hours of historical research and the expertise of educational tour planners -- all of the essential behind- the-scenes work that isn't covered by the price tag of attending a tour. Thank you to our members and donors for making it possible for us to offer these unique experiences to our community. Thank You! Barbara Sweeney – 40 days Janene Bertoncelj – 39 days Cynthia Schuele – 39 days New Booklet Design! Released early January Includes itineraries! Tour or Trek? Tours are two- to six-hour jaunts and include walking and bus tours Treks are usually overnight trips, or they visit areas more than 50 miles from Denver Annual Registration Fee ↘ New in 2019 will be a reduced, one-time, non- refundable, annual registration fee of $5 that goes towards the processing and handling of all History Colorado reservations in the Tours & Treks program. -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas By Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate National Park Service, Southwest Regional Office Series Number Acknowledgments This book would not be possible without the full cooperation of the men and women working for the National Park Service, starting with the superintendents of the two parks, Frank Deckert at Carlsbad Caverns National Park and Larry Henderson at Guadalupe Mountains National Park. One of the true joys of writing about the park system is meeting the professionals who interpret, protect and preserve the nation’s treasures. Just as important are the librarians, archivists and researchers who assisted us at libraries in several states. There are too many to mention individuals, so all we can say is thank you to all those people who guided us through the catalogs, pulled books and documents for us, and filed them back away after we left. One individual who deserves special mention is Jed Howard of Carlsbad, who provided local insight into the area’s national parks. Through his position with the Southeastern New Mexico Historical Society, he supplied many of the photographs in this book. We sincerely appreciate all of his help. And finally, this book is the product of many sacrifices on the part of our families. This book is dedicated to LauraLee and Lucille, who gave us the time to write it, and Talia, Brent, and Megan, who provide the reasons for writing. Hal Rothman Dan Holder September 1998 i Executive Summary Located on the great Permian Uplift, the Guadalupe Mountains and Carlsbad Caverns national parks area is rich in prehistory and history. -

Jaycees Award Bowling Citations

WEEK'S PLETE TELE ISION PROGRAMS UNDAY N RTH JERSEY'S ONLY WEEKLY PICTORIAL-. MAGAZINE News Highlights of ..!•'..i.... Clifton P''?:::...:?:?: ::-:-:.'::-.-: :.-........ :-:-....:.:-:-:::::'i:?.'5"::•'• •!:5'.-.:::..-.................-...-.-..:'..-..-:-:::.:-.', •., :.. iii!:::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::.-:•!:i:i:i:i:i:.:i:i:l:i:i:!.'.-':i:i•:i.i:i:!:P'::'"' .........'-"':::::!:?:i:•::i:iii?ih-'::•:::•-Y::!:':i:::i:?:!-•:. -:i:::.::i.'.-:::::?.•:•.. • •..-:..-',, •......-'.:•'..................................... .......... '.'::................................. :..... ':::':::i:i•.•-•::'..:::::i.-"!.:i:!.'.................•::i•:•:•.__•L.,• .,,•.'........................... .........:::'.........:L::::• -:,.• .•:::.- ) East Paterson •:!i: :::::::::::::::::::::.:.......:.-.•i::.:::i .:?•i?:.•:'::....... :i:. 'i' .•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•.•:•:•:•:•:•*:::•:•:•:•:•:•:•:•::•.....•.•!:}!:•!.•{:::::::::::::::::::.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.:.::.:.:..:.:.•::}:.:•::•::..:.:.:..•:::•i•.........•:::::•:.:•:•,.•:!::•-...- ............' .:":.::::i!!.i:.'"•:/'}•:•"l?????: -: ß'!?!•??•:i-"- ..'." - :-•.:?:?:?:?:.::?:?:.'-.-:l--".-'.":.".'•i ::.:' ================================================================================================================================== :'. :::?:?::?:?:•..:-'.:.:'?:':'.-:?:?:?:?:?.".-:?:?:?:?•.':'%'?: Fir Lawn • '!!i{{•i•}iii!i!!i•i•!•''•' [i•:{•...................................... :::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::::: ...........:.$:•..... !::::{{{{i!:::•.: :• :::::::::::::::::::::::':":':'•i:::::: -

Allen Rostron, the Law and Order Theme in Political and Popular Culture

OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM OKLAHOMA CITY UNIVERSITY LAW REVIEW VOLUME 37 FALL 2012 NUMBER 3 ARTICLES THE LAW AND ORDER THEME IN POLITICAL AND POPULAR CULTURE Allen Rostron I. INTRODUCTION “Law and order” became a potent theme in American politics in the 1960s. With that simple phrase, politicians evoked a litany of troubles plaguing the country, from street crime to racial unrest, urban riots, and unruly student protests. Calling for law and order became a shorthand way of expressing contempt for everything that was wrong with the modern permissive society and calling for a return to the discipline and values of the past. The law and order rallying cry also signified intense opposition to the Supreme Court’s expansion of the constitutional rights of accused criminals. In the eyes of law and order conservatives, judges needed to stop coddling criminals and letting them go free on legal technicalities. In 1968, Richard Nixon made himself the law and order candidate and won the White House, and his administration continued to trumpet the law and order theme and blame weak-kneed liberals, The William R. Jacques Constitutional Law Scholar and Professor of Law, University of Missouri–Kansas City School of Law. B.A. 1991, University of Virginia; J.D. 1994, Yale Law School. The UMKC Law Foundation generously supported the research and writing of this Article. 323 OCULREV Fall 2012 Rostron 323-395 (Do Not Delete) 12/17/2012 10:59 AM 324 Oklahoma City University Law Review [Vol. 37 particularly judges, for society’s ills. -

Wild West Photograph Collection

THE KANSAS CITY PUBLIC LIBRARY Wild West Photograph Collection This collection of images primarily relates to Western lore during the late 19th and parts of the 20th centuries. It includes cowboys and cowgirls, entertainment figures, venues as rodeos and Wild West shows, Indians, lawmen, outlaws and their gangs, as well as criminals including those involved in the Union Station Massacre. Descriptive Summary Creator: Brookings Montgomery Title: Wild West Photograph Collection Dates: circa 1880s-1960s Size: 4 boxes, 1 3/4 cubic feet Location: P2 Administrative Information Restriction on access: Unrestricted Terms governing use and reproduction: Most of the photographs in the collection are reproductions done by Mr. Montgomery of originals and copyright may be a factor in their use. Additional physical form available: Some of the photographs are available digitally from the library's website. Location of originals: Location of original photographs used by photographer for reproduction is unknown. Related sources and collections in other repositories: Ralph R. Doubleday Rodeo Photographs, Donald C. & Elizabeth Dickinson Research center, National Cowboy and Western Heritage Museum, Oklahoma City, Oklahoma. See also "Ikua Purdy, Yakima Canutt, and Pete Knight: Frontier Traditions Among Pacific Basin Rodeo Cowboys, 1908-1937," Journal of the West, Vol. 45, No.2, Spring, 2006, p. 43-50. (Both Canutt and Knight are included in the collection inventory list.) Acquisition information: Primarily a purchase, circa 1960s. Citation note: Wild West Photograph Collection, Missouri Valley Special Collections, Kansas City Public Library, Kansas City, Missouri. Collection Description Biographical/historical note The Missouri Valley Room was established in 1960 after the Kansas City Public Library moved into its then new location at 12th and Oak in downtown Kansas City. -

Chapter 5: Vectors of Settlement

Chapter 5: Vectors of Settlement By the time Mexican soldiers killed Victorio and his followers in the mountains of northern Mexico in October 1880, the Guadalupe Mountains and the trans-Pecos region had already acquired a new sedentary population. An increasing number of Anglo-American and Hispano settlers lived within the boundaries of the Mescalero homeland. To the west, the fertile Mesilla valley had long been a stronghold of Hispano livestock farmers, some of whom grazed animals in the various mountain ranges during the summers; later they explored opportunities to ranch or farm in the region. Finding land expensive and rare along the Rio Grande, still more sought to try their hand at ranching or farming outside the confines of the fertile valley. Others trickled south from Las Vegas, New Mexico, and the Mora area, initially trailing sheep and sometimes a few cows. Some settled along the rivers and streams that passed through the region. Few in the trans-Pecos expected to find wealth in agriculture; only the most savvy, creative, and entrepreneurial stood a chance at achieving such a goal even in the lucrative industry of ranching during its military-supported heyday in the 1860s and 1870s. Other opportunities drew Anglo-Americans to the trans-Pecos. To the north of the Guadalupe Mountains, the two military forts — Stanton and Sumner — became magnets for people who sought to provide the Army with the commodities it needed to feed, clothe, and shelter soldiers and to fill its obligations to reservation Indians. Competition for such contracts provided one of the many smouldering problems that played a part in initiating the Lincoln County War of 1878. -

Cowboys and Lawyers

COWBOYS AND LAWYERS $5,000 REWARD, DEAD OR ALIVE! appears in Done in the Open: Drawings by Frederick Remington (1902), which contained an introduction and “verses” by Owen Wister; it was included as one of the illustrations in a 1929 edition of Wister’s The Virginian. Kansas History: A Journal of the Central Plains 30 (Spring 2007): 52–63 52 Kansas History Ambivalence and Myth in the History and Literature of the Southern Plains by Robert A. Mead he personas of the cowboy and the gunslinger are central characters in both the American na- tional identity and the myth of the West. Throughout the twentieth century Hollywood and western print fi ction explored a number of key American themes, such as individualism and the morality of violence, through exploration of the real and imagined history of the Great Plains Tand the American West. So many western fi lms, television shows, and books have been cast in the ranches, cattle drives, and cattle towns of Kansas and the Southern Plains that names such as Bat Masterson, Charles Goodnight, and Wyatt Earp have been added to the American mythic pantheon. This element in the na- tional identity is ingrained quite deeply, to the point that President George W. Bush, in response to the ter- rorist attacks of September 11, 2001, invoked the imagery of the western myth by stating, “I want justice. And there’s an old poster out West, as I recall, that said, ‘Wanted: Dead or Alive.’”1 The myth of the West is interwoven with historical characters and situations. -

Texas Pecos Trail Region

Frontier Spirit in Big Sky Country ★ ★ ★ ★ ★ igh tabletop mesas rise from wide-open prairies. Ancient rivers course through sheer limestone canyons. Cool artesian springs bubble up from deep underground and ceaseless wind sculpts sand into ever-changing dunes. Above it all stretches a sky so big you can almost reach out and touch it. This is the legendary Wild West of classic books and movies, and the real-life landscape of the Texas Pecos Trail Region. The region’s 22 West Texas counties cover almost 35,000 square miles, an area larger than a dozen average-sized U.S. states. This big land comprises an ecological transition zone at the junction of the high and rolling plains in the north, Edwards Plateau in the east, mountain basins and Chihuahuan Desert in the west and brush country in the south. For centuries, scattered Native American groups hunted buffalo and other game across the immense UTSA’s InstituteUTSA’s Cultures, of Texan #068-0154 grassland prairies. These same groups also used plant Comanche warrior resources and created large plant processing and baking features on the landscape. Dry caves and Th e front cover photo was taken at the American Airpower Heritage rock shelters in the Lower Pecos canyon lands display Museum in Midland, which houses one of the world’s largest collections native rock art and preserve material evidence of the of World War II aircraft nose art. Th ese original nose art panels are titled “Save the Girls” and represent the artistic expressions of World prehistoric lifeways. Later, Native Americans such as War II bomber pilots. -

“Off the Beaten Path” by Carl Langford Author, Howard Bryan, a Veteran Newspaper and Author of the Old West History. He

“Off the Beaten Path” by Carl Langford Author, Howard Bryan, a veteran newspaper and author of the old West history. He went to Albuquerque, NM. in 1948, and interviewed about 100 pioneers of the age of 85+ each with a story about all walks of life in the early days. This trip to Albuquerque turned his life around, the old west got in his blood. In Ohio, he was writing about frontier history, about dead people. He wrote a history column “Know Your Ohio”. He would go on to write books on Western History. He died in 2011 at age of 91 from terminal cancer. Compiled from his interview with Pioneer Casey and Casey family History. In his early interviews with old pioneers he was told about a cattle rancher around Los Lunas, NM. his name “Shepard S Casey” . a brother to my wife’s grandfather William Cap Casey, a long time resident of Coleman County. There father, William John Casey born 3 Dec 1839 TN. In 1863 married Lucy T. Holt of Virginia born seven sons and two daughters. The family came to Texas by wagon in 1870 settling near Arlington, Tarrant Co., Tx. Lucy died 12 Mar 1884, 4 days later the baby died, both buried at Johnson Station Cemetery, which is now in Arlington. (Unmarked Grave). John brought 189 acres of land on Old Coleman-Comanche road two miles from Brown Co., Tx. in 1888 and continued to raise all his children to adulthood. With ailing heath, he went to live with daughter in Duncan Okla. He was buried there in 1932. -

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place - Carlsbad Caverns

Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place - Carlsbad Caverns Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas by Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate 1998 Department of the Interior National Park Service Washington, DC Continue Last Updated: 22-April-2003 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/CarlsbadCav/[12/14/2012 12:49:22 PM] Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place - Carlsbad Caverns - Table of Contents Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place A Historic Resource Study of Carlsbad Caverns and Guadalupe Mountains National Parks and the Surrounding Areas by Hal K. Rothman Daniel Holder, Research Associate 1998 Department of the Interior National Park Service Washington, DC TABLE OF CONTENTS Cover Page Acknowledgements, Executive Summary List of Illustrations, List of Maps Introduction Maps Chapter 1: From Prehistory to European Contact Chapter 2: The Spanish and Mexican Era Chapter 3: The American Appearance Chapter 4: The Military Seeks Control Chapter 5: Vectors of Settlement Photos 1 http://www.nps.gov/history/history/online_books/CarlsbadCav/toc.htm[12/14/2012 12:49:26 PM] Promise Beheld and the Limits of Place - Carlsbad Caverns - Table of Contents Photos 2 Chapter 6: Aspirations and Realities Chapter 7: A Stronger Federal Presence Chapter 8: Carlsbad Caverns in the Post-War Era Chapter 9: A Southern Cornerstone in a Subregion: Guadalupe Mountains National Park Epilogue: Parks in the Post Industrial World Bibliography Sources Consulted Note: There are some formatting differences between the original printed publication and the electronic version of this book.