07-David Scott

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Jamaica in the Tourism Global Value Chain

Jamaica in the Tourism Global Value Chain April 2018 Prepared by Karina Fernandez-Stark and Penny Bamber Contributing researcher: Vivian Couto, Jack Daly and Danny Hamrick Duke Global Value Chains Center, Duke University Global Value Chains Center This research was prepared by the Duke University Global Value Chains Center on behalf of the Organization of American States (OAS). This study is part of the establishment of Small Business Development Centers in the Caribbean. The report is based on both primary and secondary information sources. In addition to interviews with firms operating in the sector and supporting institutions, the report draws on secondary research and information sources. The project report is available at www.gvcc.duke.edu. Acknowledgements The Duke University Global Value Chains Center would like to thank all of the interviewees, who gave generously of their time and expertise, as well as Renee Penco of the Organization of American States (OAS) for her extensive support. The Duke University Global Value Chain Center undertakes client-sponsored research that addresses economic and social development issues for governments, foundations and international organizations. We do this principally by utilizing the global value chain (GVC) framework, created by Founding Director Gary Gereffi, and supplemented by other analytical tools. As a university- based research center, we address clients’ real-world questions with transparency and rigor. www.gvcc.duke.edu. Duke Global Value Chain Center, Duke University © April 2018 -

1 Corruption, Organized Crime and Regional Governments in Peru Lucia

Corruption, organized crime and regional governments in Peru Lucia Dammert1 & Katherine Sarmiento2 Abstract Decentralization in a context of state´s structural weakness and growth of illegal economies is a fertile ground for corruption and impunity. Although corruption is not a new element of Peruvian politics, its characteristics at the regional level depict a bleak scenario. This chapter focuses on corruption cases linked to political leaders that participated in the last two regional elections in Peru (2010 and 2014). Multiple elements involved in most cases are analyzed in a systematic way defining a political process that includes a charismatic leader, a dense family network, a populist political movement, a frail campaign finance regulation and apparent links with criminal organizations. Although some legal changes have been implemented, there is a clear need for a profound political reform that would include revisiting the decentralization process as well as developing an structural justice reform initiative. Introduction Corruption is an important issue in Peru. The corruption perception index published by Transparency International shows that globally Peru has gone from place 72 to 101 (out of 175) between 2010 and 2016. As mentioned by Transparency International, countries that are located in the lower end of the scale are “plagued by untrustworthy and badly functioning public institutions like the police and judiciary. Even where anti-corruption laws are on the books, in practice they're often skirted or ignored”3. Within Latin America, the perception of corruption in Peru has also increased. According to the Global Corruption Barometer (2017), 62 percent of Latin Americans believe that corruption levels increased compared to the previous year. -

Machu Picchu Was Rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911

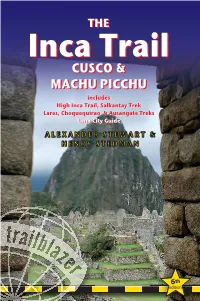

Inca-6 Back Cover-Q8__- 22/9/17 10:13 AM Page 1 TRAILBLAZER Inca Trail High Inca Trail, Salkantay, Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks + Lima Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks Salkantay, High Inca Trail, THETHE 6 EDN ‘...the Trailblazer series stands head, shoulders, waist and ankles above the rest. Inca Trail They are particularly strong on mapping...’ Inca Trail THE SUNDAY TIMES CUSCOCUSCO && Lost to the jungle for centuries, the Inca city of Machu Picchu was rediscovered by MACHU PICCHU Hiram Bingham in 1911. It’s now probably MACHU PICCHU the most famous sight in South America – includesincludes and justifiably so. Perched high above the river on a knife-edge ridge, the ruins are High Inca Trail, Salkantay Trek Cusco & Machu Picchu truly spectacular. The best way to reach Lares, Choquequirao & Ausangate Treks them is on foot, following parts of the original paved Inca Trail over passes of Lima City Guide 4200m (13,500ft). © Henry Stedman ❏ Choosing and booking a trek – When Includes hiking options from ALEXANDER STEWART & to go; recommended agencies in Peru and two days to three weeks with abroad; porters, arrieros and guides 35 detailed hiking maps HENRY STEDMAN showing walking times, camp- ❏ Peru background – history, people, ing places & points of interest: food, festivals, flora & fauna ● Classic Inca Trail ● High Inca Trail ❏ – a reading of The Imperial Landscape ● Salkantay Trek Inca history in the Sacred Valley, by ● Choquequirao Trek explorer and historian, Hugh Thomson Plus – new for this edition: ❏ Lima & Cusco – hotels, -

What's Next for Business in Peru?

ARTICLE Giant Pencils and Straw Hats: What’s Next for Business in Peru? Following a razor-thin voting margin, the Peruvian population elected schoolteacher and left-wing candidate, Pedro Castillo, to the presidency. Castillo’s election has brought uncertainty to businesses in Peru due to a palpable fear of radical leftist reforms that would threaten Peru’s image as a nation welcoming of foreign investment. However, those concerns may be premature and overblown. We believe that Castillo is likely to step back from necessary legislative support to achieve meaningful changes implementing the sort of radical change promised during to the Peruvian economy will be a difficult task for a new, the run-up to the election. Promises made during campaigns inexperienced president with a very limited mandate and an are frequently disregarded when governing, and we believe obstructive Congress. a pragmatism is likely to prevail. Castillo has limited Castillo’s election looks more like Humala in 2011 (or Lula maneuvering room and will focus his attention on fixing in 2002) than Chávez in 1998, with the new Peruvian the obvious divide within the country and regenerating president likely to maintain a market friendly economy the heavily COVID-19 hit economy. Even if he is pressured coupled with an increased focus on programs to attempt to to implement anti-market reforms – possibly as a result of address social inequality. pressure from stalwarts in his party Peru Libre – gathering the GiaNT PENcilS AND StraW HatS: What’S NeXT FOR BUSINESS IN PerU? FTI -

Political Development in Peru Jean Carriere Thesis Submitted to The

c Political Development in Peru Jean Carriere Thesis submitted to the Faculty of Graduate Studies, MoGill Univ6~ity, in partial ful filment of the requirements for the degree of Master of Arts. Department of Economics and Political Science April, 1967. o @ Jean Carriere 1967 PREFACE This study deals with the political system of Peru in terms of categories of analysis that have not previously been used explicitly in relation to that country. The analysis focuses on a selected number of processes that have been found by contemporary polit ical theorists to be highly relevant for politics in the context of modernization. Although there is no attempt, here, to give a total picture of the deter minants of the political process in Peru, the perspec tive that has been selected should add a new dimension to our understanding of political change in that coun try. It should help us to establish whether the polit ical system in Peru is becoming more or less viable, more or less able to cope with the increasingly complex problems with which it is confronted, more or less ftdeveloped" • I am deeply grateful to Professor Baldev Raj Nayar, of McGill University, for his constant advice and encouragement throughout the research and writing phases for this study. Professor Nayarts graduate seminar in Political Development kindled my interest in this area and provided the inspiration for the concept ual framework. Jean Carriere c McGill University. CONTENTS I. Political Development in Transitional Societies 1 II. Social Mobilization in Peru: A Major Source of Tension 20 lIT. Bottlenecks to Institutionalization: The Armed Forces and the Oligarchy 52 IV. -

I V Public Childhoods: Street Labor, Family, and the Politics of Progress

Public Childhoods: Street Labor, Family, and the Politics of Progress in Peru by Leigh M. Campoamor Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Diane Nelson ___________________________ Irene Silverblatt ___________________________ Rebecca Stein ___________________________ Elizabeth Chin Dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 i v ABSTRACT Public Childhoods: Street Labor, Family, and the Politics of Progress in Peru by Leigh M. Campoamor Department of Cultural Anthropology Duke University Date:_______________________ Approved: ___________________________ Orin Starn, Supervisor ___________________________ Diane Nelson ___________________________ Irene Silverblatt ___________________________ Rebecca Stein ___________________________ Elizabeth Chin An abstract of a dissertation submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in the Department of Cultural Anthropology in the Graduate School of Duke University 2012 Copyright by Leigh M. Campoamor 2012 Abstract This dissertation focuses on the experiences of children who work the streets of Lima primarily as jugglers, musicians, and candy vendors. I explore how children’s everyday lives are marked not only by the hardships typically associated with poverty, but also by their -

Iv PERU Peru and the Peruvians

iv PERU Peru and the Peruvians The paradoxical co-existence of abundant natural wealth and pervasive human poverty is something that has struck generations of visitors to Peru. With its mineral reserves, oil, and gas, its fish resources, and its diverse agriculture, it is a country that should generate wealth for all to share. In reality, however, more than half of Peru's population earns less than the equivalent of two dollars a day. As the geographer Antonio Raimondi famously remarked, Peru is like a beggar seated on a bench of gold. With their nose for gold and silver, the Spanish conquerors - or conquistadores - were swift to realise Peru's economic potential. From the mid-i6th century onwards they turned Peru into the centre of an empire, the main function of which was to finance the Spanish crown's seemingly inexhaustible appetite for war. In the 19th century, following Peru's independence from Spain, the British and Americans - defying all geographical logic - built railways across the Andes in order to extract copper and silver from the mines of the Peruvian highlands, or sierra. More recently, foreign multinational companies have opened up new mining ventures, such as Yanacocha near Cajamarca, and Antamina in •4 Francisco Lama jokes with one of her many grandchildren. Like many other citizens, Francisca believes that the future of their town - Tambo Grande in Piura - is under threat from mining developments. • Grass-roots organisations are increasingly demanding that their voices be heard throughout Peru. The women's groups taking part in this rally in Santo Domingo, Piura, were able to meet the mayor, and to present their proposals for change to him. -

Veracity Or Falsehood in the Presidential Elections of Peru and Extreme Parties

Preprints (www.preprints.org) | NOT PEER-REVIEWED | Posted: 12 May 2021 doi:10.20944/preprints202105.0274.v1 Veracity or Falsehood in the presidential elections of Peru and extreme parties. Israel Mallma¹ ,, Lita Salazar² ¹ Doctor in Mining Safety and Control, Master's in mining management, Faculty of Mining Engineering, Graduate School of the National University of the Center of Peru; [email protected] ² Doctor in Educational Sciences, Master's in educational management, Faculty of Education, graduate school of the National University of the Center of Peru; [email protected] Abstract Background and objectives: In the current context, the 2021 presidential elections in Peru distance from the social objective, not being objectively represented, that is why we analyze their validity, we determine the distances between the parties if they are extreme, the correspondences with the departments and their prospects, in the surveys we propose which departments influence the results. Methods: We use a mixed methodology, qualitative analysis, it will be multidimensional with the support of statistical methods and programs such as R Studio, worddj, Gephi, and Iramuteq. The quantitative analysis will be through factor analysis, correspondence and discriminant analysis to the data of the election Results and conclusions: The textual analysis mentions that there are dimensions such as the social issue, the results of the surveys and democracy that are far apart, regarding the electoral issue. This inculcates to work both on the part of the organisms that carry out these processes, as well as the initiative of the candidates, and the media. Regarding the quantitative analysis, it is detailed that the representative parties must be greater than 4.0 million voters, to make representative parties at the national level. -

Voting in the Shadow of Violence: Electoral Politics and Conflict

Voting in the Shadow of Violence: Electoral Politics and Conflict Jóhanna Kristín Birnir Associate Professor Department of Government and Politics University of Maryland [email protected] Anita Gohdes PhD Candidate Department of Political Science University of Mannheim [email protected] Abstract: In the context of political violence, the common assumption that the democratic electoral process guarantees accountability has increasingly come under fire. We argue that the aggregate evidence supporting this critique is, at times, incomplete. Instead, we contend that responsible parties are often held accountable at the polls, but only by those directly exposed to violence. In contrast, voters learning about violence from afar will punish governing parties only when they fail to curb the violence. To test our expectations we estimate reliable levels of provincial-level conflict violence and match the data with provincial-level presidential vote shares from two consecutive Peruvian elections held during the height of civil war. The analysis supports our theory of discriminating electoral punishment, with important implications for our understanding of mobilization and political participation in conflicts. Introduction Violence is almost always perpetrated in concentrated locations (Rustad et al., 2011). At the same time, within a country, voters experiencing violence from afar are much more numerous than those directly affected by it. If local violence has a different effect on voter political expression in election than does violence experienced from afar, the effects are confounded at the national level. For example, if voters only punish parties locally for violence committed by an associated perpetrator, then insurgent associated parties can increase their party’s national vote share while still being punished locally where the insurgents perpetrate violence. -

1 Multipart Xf8ff 5 Return of the Native.Qxd

The Return of the Native: The Indigenous Challenge in Latin America Rodolfo Stavenhagen Institute of Latin American Studies 31 Tavistock Square London WC1H 9HA The Institute of Latin American Studies publishes as Occasional Papers selected seminar and conference papers and public lectures delivered at the Institute or by scholars associated with the work of the Institute. This paper was first given as The John Brooks Memorial Lecture in The Chancellor's Hall, Senate House, University of London, on 15 March 2002. Rodolfo Stavenhagen, Research-Professor in sociology at El Colegio de México (Mexico), is currently United Nations Special Rapporteur for the Human Rights of Indigenous People. He is Vice-President of the Inter- American Institute of Human Rights and member of the Council of the United Nations University for Peace. He is a former Assistant-Director General for Social Sciences at UNESCO. His books include Derechos humanos de los pueblos indígenas (2000); Ethnic Conflicts and the Nation-State (1996); The Ethnic Question: Development, Conflict and Human Rights(1990); and Entre la ley y la costumbre: el derecho consuetudinario indígena en América Latina (1990). Occasional Papers, New Series 1992– ISSN 0953 6825 © Institute of Latin American Studies University of London, 2002 The Return of the Native: The Indigenous Challenge in Latin America Rodolfo Stavenhagen The Polemical Encounter of Two Worlds When Cortés conquered Tenochtitlan almost five hundred years ago, the chronicler Bernal Díaz del Castillo wrote some years after the deed that had it not been for Malintzin, an Indian woman who served Cortés as interpreter, the conquest of the fabulous Aztec empire might not have taken place. -

Civilian Participation in Politics and Violent Revolution: Ideology, Networks, and Action in Peru and India

CIVILIAN PARTICIPATION IN POLITICS AND VIOLENT REVOLUTION: IDEOLOGY, NETWORKS, AND ACTION IN PERU AND INDIA A Dissertation submitted to the Faculty of the Graduate School of Arts and Sciences of Georgetown University in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the degree of Doctor of Philosophy in Government By Devin M. Finn, M.A. Washington, DC May 25, 2016 Copyright 2017 by Devin M. Finn All Rights Reserved ii CIVILIAN PARTICIPATION IN POLITICS AND VIOLENT REVOLUTION: IDEOLOGY, NETWORKS, AND ACTION IN PERU AND INDIA Devin Finn, M.A. Thesis Advisor: Charles King, Ph.D. ABSTRACT How and why do ordinary people in democratic states participate in violent revolution? This dissertation explores variation in the confluence of civilians’ participation in status quo politics – through electoral channels and civil society action – and in violent insurgencies that seek to conquer the state. Through a comparative juxtaposition of Peru’s Shining Path and the Naxalite movement in India, I argue that an insurgency’s particular ideological interpretations and conceptions of membership shape civilian support by influencing everyday social relations between rebels and civilians and changing networks of participation. During war, civilians are agents of political mobilization, and rebels exploit social networks, which draw on historical forms of organization and activism and a long trajectory of political ideas about race, citizenship, and class. I examine people’s varied participation in violent politics in three settings: the regions of Ayacucho and Puno, Peru (1960-1992), and Telangana, a region of southern India (1946-51). Where communities in Peru drew on existing political resources – diverse networks that expressed peasants’ demands for reform and representation, and which emphasized commitment to democratic contestation over armed struggle – people could choose to resist rebels’ mobilizing efforts. -

Takeoff and Turbulence in Modernizing Peru

Carrión, Julio F. 2019. Takeoff and Turbulence in Modernizing Peru. Latin American Research Review 54(2), pp. 499–508. DOI: https://doi.org/10.25222/larr.416 BOOK REVIEW ESSAYS Takeoff and Turbulence in Modernizing Peru Julio F. Carrión University of Delaware, US [email protected] This essay reviews the following works: Peru: Elite Power and Political Capture. By John Crabtree and Francisco Durand. London: Zed Books (distributed by University of Chicago Press), 2017. Pp. viii + 206. $29.95 paperback. ISBN: 9781783609031. Peru in Theory. Edited by Paulo Drinot. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2014. Pp. ix + 255. $105.00 hardcover. ISBN: 9781137455253. Rethinking Community from Peru: The Political Philosophy of José María Arguedas. By Irina Alexandra Feldman. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2014. Pp. ix + 175. $29.95 paperback. ISBN: 9780822963073. The Rarified Air of the Modern: Airplanes and Technological Modernity in the Andes. By Willie Hiatt. New York: Oxford University Press, 2016. Pp. vii + 215. $49.54 hardcover. ISBN: 9780190248901. Andean Truths: Transitional Justice, Ethnicity, and Cultural Production in Post–Shining Path Peru. By Anne Lambright. Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2015. Pp. vii + 212. $120.00 hardcover. ISBN: 9781781382516. Now Peru Is Mine: The Life and Times of a Campesino Activist. By Manuel Llamojha Mitma and Jaymie Patricia Heilman. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2016. Pp. ix + 229. $23.95 paperback. ISBN: 9780822362388. Peru: Staying the Course of Economic Success. Edited by Alejandro Santos and Alejandro Werner. Washington, DC: International Monetary Fund, 2015. Pp. xv + 440. $40.00 ISBN: 9781513599748. Peru reached a milestone in 2016. For the first time in its history, the country enjoyed four consecutive democratic elections, and although the economy had experienced a slowdown in the previous year, as well as a minor bump in 2009 in the wake of the 2008 global crisis, the expansive wave that started in 2002 continues.