Disclaimer: This File Has Been Scanned with an Optical Character Recognition Program, Often an Erroneous Process

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Tinamiformes – Falconiformes

LIST OF THE 2,008 BIRD SPECIES (WITH SCIENTIFIC AND ENGLISH NAMES) KNOWN FROM THE A.O.U. CHECK-LIST AREA. Notes: "(A)" = accidental/casualin A.O.U. area; "(H)" -- recordedin A.O.U. area only from Hawaii; "(I)" = introducedinto A.O.U. area; "(N)" = has not bred in A.O.U. area but occursregularly as nonbreedingvisitor; "?" precedingname = extinct. TINAMIFORMES TINAMIDAE Tinamus major Great Tinamou. Nothocercusbonapartei Highland Tinamou. Crypturellus soui Little Tinamou. Crypturelluscinnamomeus Thicket Tinamou. Crypturellusboucardi Slaty-breastedTinamou. Crypturellus kerriae Choco Tinamou. GAVIIFORMES GAVIIDAE Gavia stellata Red-throated Loon. Gavia arctica Arctic Loon. Gavia pacifica Pacific Loon. Gavia immer Common Loon. Gavia adamsii Yellow-billed Loon. PODICIPEDIFORMES PODICIPEDIDAE Tachybaptusdominicus Least Grebe. Podilymbuspodiceps Pied-billed Grebe. ?Podilymbusgigas Atitlan Grebe. Podicepsauritus Horned Grebe. Podicepsgrisegena Red-neckedGrebe. Podicepsnigricollis Eared Grebe. Aechmophorusoccidentalis Western Grebe. Aechmophorusclarkii Clark's Grebe. PROCELLARIIFORMES DIOMEDEIDAE Thalassarchechlororhynchos Yellow-nosed Albatross. (A) Thalassarchecauta Shy Albatross.(A) Thalassarchemelanophris Black-browed Albatross. (A) Phoebetriapalpebrata Light-mantled Albatross. (A) Diomedea exulans WanderingAlbatross. (A) Phoebastriaimmutabilis Laysan Albatross. Phoebastrianigripes Black-lootedAlbatross. Phoebastriaalbatrus Short-tailedAlbatross. (N) PROCELLARIIDAE Fulmarus glacialis Northern Fulmar. Pterodroma neglecta KermadecPetrel. (A) Pterodroma -

Houde2009chap64.Pdf

Cranes, rails, and allies (Gruiformes) Peter Houde of these features are subject to allometric scaling. Cranes Department of Biology, New Mexico State University, Box 30001 are exceptional migrators. While most rails are generally MSC 3AF, Las Cruces, NM 88003-8001, USA ([email protected]) more sedentary, they are nevertheless good dispersers. Many have secondarily evolved P ightlessness aJ er col- onizing remote oceanic islands. Other members of the Abstract Grues are nonmigratory. 7 ey include the A nfoots and The cranes, rails, and allies (Order Gruiformes) form a mor- sungrebe (Heliornithidae), with three species in as many phologically eclectic group of bird families typifi ed by poor genera that are distributed pantropically and disjunctly. species diversity and disjunct distributions. Molecular data Finfoots are foot-propelled swimmers of rivers and lakes. indicate that Gruiformes is not a natural group, but that it 7 eir toes, like those of coots, are lobate rather than pal- includes a evolutionary clade of six “core gruiform” fam- mate. Adzebills (Aptornithidae) include two recently ilies (Suborder Grues) and a separate pair of closely related extinct species of P ightless, turkey-sized, rail-like birds families (Suborder Eurypygae). The basal split of Grues into from New Zealand. Other extant Grues resemble small rail-like and crane-like lineages (Ralloidea and Gruoidea, cranes or are morphologically intermediate between respectively) occurred sometime near the Mesozoic– cranes and rails, and are exclusively neotropical. 7 ey Cenozoic boundary (66 million years ago, Ma), possibly on include three species in one genus of forest-dwelling the southern continents. Interfamilial diversifi cation within trumpeters (Psophiidae) and the monotypic Limpkin each of the ralloids, gruoids, and Eurypygae occurred within (Aramidae) of both forested and open wetlands. -

An Update of Wallacels Zoogeographic Regions of the World

REPORTS To examine the temporal profile of ChC produc- specification of a distinct, and probably the last, 3. G. A. Ascoli et al., Nat. Rev. Neurosci. 9, 557 (2008). tion and their correlation to laminar deployment, cohort in this lineage—the ChCs. 4. J. Szentágothai, M. A. Arbib, Neurosci. Res. Program Bull. 12, 305 (1974). we injected a single pulse of BrdU into pregnant A recent study demonstrated that progeni- CreER 5. P. Somogyi, Brain Res. 136, 345 (1977). Nkx2.1 ;Ai9 females at successive days be- tors below the ventral wall of the lateral ventricle 6. L. Sussel, O. Marin, S. Kimura, J. L. Rubenstein, tween E15 and P1 to label mitotic progenitors, (i.e., VGZ) of human infants give rise to a medial Development 126, 3359 (1999). each paired with a pulse of tamoxifen at E17 to migratory stream destined to the ventral mPFC 7. S. J. Butt et al., Neuron 59, 722 (2008). + 18 8. H. Taniguchi et al., Neuron 71, 995 (2011). label NKX2.1 cells (Fig. 3A). We first quanti- ( ). Despite species differences in the develop- 9. L. Madisen et al., Nat. Neurosci. 13, 133 (2010). fied the fraction of L2 ChCs (identified by mor- mental timing of corticogenesis, this study and 10. J. Szabadics et al., Science 311, 233 (2006). + phology) in mPFC that were also BrdU+. Although our findings raise the possibility that the NKX2.1 11. A. Woodruff, Q. Xu, S. A. Anderson, R. Yuste, Front. there was ChC production by E15, consistent progenitors in VGZ and their extended neurogenesis Neural Circuits 3, 15 (2009). -

Appendix, French Names, Supplement

685 APPENDIX Part 1. Speciesreported from the A.O.U. Check-list area with insufficient evidencefor placementon the main list. Specieson this list havebeen reported (published) as occurring in the geographicarea coveredby this Check-list.However, their occurrenceis considered hypotheticalfor one of more of the following reasons: 1. Physicalevidence for their presence(e.g., specimen,photograph, video-tape, audio- recording)is lacking,of disputedorigin, or unknown.See the Prefacefor furtherdiscussion. 2. The naturaloccurrence (unrestrained by humans)of the speciesis disputed. 3. An introducedpopulation has failed to becomeestablished. 4. Inclusionin previouseditions of the Check-listwas basedexclusively on recordsfrom Greenland, which is now outside the A.O.U. Check-list area. Phoebastria irrorata (Salvin). Waved Albatross. Diornedeairrorata Salvin, 1883, Proc. Zool. Soc. London, p. 430. (Callao Bay, Peru.) This speciesbreeds on Hood Island in the Galapagosand on Isla de la Plata off Ecuador, and rangesat seaalong the coastsof Ecuadorand Peru. A specimenwas takenjust outside the North American area at Octavia Rocks, Colombia, near the Panama-Colombiaboundary (8 March 1941, R. C. Murphy). There are sight reportsfrom Panama,west of Pitias Bay, Dari6n, 26 February1941 (Ridgely 1976), and southwestof the Pearl Islands,27 September 1964. Also known as GalapagosAlbatross. ThalassarchechrysosWma (Forster). Gray-headed Albatross. Diornedeachrysostorna J. R. Forster,1785, M6m. Math. Phys. Acad. Sci. Paris 10: 571, pl. 14. (voisinagedu cerclepolaire antarctique & dansl'Ocean Pacifique= Isla de los Estados[= StatenIsland], off Tierra del Fuego.) This speciesbreeds on islandsoff CapeHorn, in the SouthAtlantic, in the southernIndian Ocean,and off New Zealand.Reports from Oregon(mouth of the ColumbiaRiver), California (coastnear Golden Gate), and Panama(Bay of Chiriqu0 are unsatisfactory(see A.O.U. -

Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016

Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 SOUTHEAST BRAZIL: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna October 20th – November 8th, 2016 TOUR LEADER: Nick Athanas Report and photos by Nick Athanas Helmeted Woodpecker - one of our most memorable sightings of the tour It had been a couple of years since I last guided this tour, and I had forgotten how much fun it could be. We covered a lot of ground and visited a great series of parks, lodges, and reserves, racking up a respectable group list of 459 bird species seen as well as some nice mammals. There was a lot of rain in the area, but we had to consider ourselves fortunate that the rainiest days seemed to coincide with our long travel days, so it really didn’t cost us too much in the way of birds. My personal trip favorite sighting was our amazing and prolonged encounter with a rare Helmeted Woodpecker! Others of note included extreme close-ups of Spot-winged Wood-Quail, a surprise Sungrebe, multiple White-necked Hawks, Long-trained Nightjar, 31 species of antbirds, scope views of Variegated Antpitta, a point-blank Spotted Bamboowren, tons of colorful hummers and tanagers, TWO Maned Wolves at the same time, and Giant Anteater. This report is a bit light on text and a bit heavy of photos, mainly due to my insane schedule lately where I have hardly had any time at home, but all photos are from the tour. www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Tropical Birding Trip Report Southeast Brazil: Atlantic Rainforest and Savanna, Oct-Nov 2016 The trip started in the city of Curitiba. -

Attempting to See One Member of Each of the World's Bird Families Has

Attempting to see one member of each of the world’s bird families has become an increasingly popular pursuit among birders. Given that we share that aim, the two of us got together and designed what we believe is the most efficient strategy to pursue this goal. Editor’s note: Generally, the scientific names for families (e.g., Vireonidae) are capital- ized, while the English names for families (e.g., vireos) are not. In this article, however, the English names of families are capitalized for ease of recognition. The ampersand (&) is used only within the name of a family (e.g., Guans, Chachalacas, & Curassows). 8 Birder’s Guide to Listing & Taxonomy | October 2016 Sam Keith Woods Ecuador Quito, [email protected] Barnes Hualien, Taiwan [email protected] here are 234 extant bird families recognized by the eBird/ Clements checklist (2015, version 2015), which is the offi- T cial taxonomy for world lists submitted to ABA’s Listing Cen- tral. The other major taxonomic authority, the IOC World Bird List (version 5.1, 2015), lists 238 families (for differences, see Appendix 1 in the expanded online edition). While these totals may appear daunting, increasing numbers of birders are managing to see them all. In reality, save for the considerable time and money required, finding a single member of each family is mostly straightforward. In general, where family totals or family names are mentioned below, we use the eBird/Clements taxonomy unless otherwise stated. Family Feuds: How do world regions compare? In descending order, the number of bird families supported by con- tinental region are: Asia (125 Clements/124 IOC), Africa (122 Clem- ents/126 IOC), Australasia (110 Clements/112 IOC), North America (103 Clements/IOC), South America (93 Clements/94 IOC), Europe (73 Clements/74 IOC ), and Antarctica (7 Clements/IOC). -

Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (And 113 Non-Species Taxa) in Accordance with the 62Nd AOU Supplement (2021), Sorted Taxonomically

Four-letter (English Name) and Six-letter (Scientific Name) Alpha Codes for 2168 Bird Species (and 113 Non-Species Taxa) in accordance with the 62nd AOU Supplement (2021), sorted taxonomically Prepared by Peter Pyle and David F. DeSante The Institute for Bird Populations www.birdpop.org ENGLISH NAME 4-LETTER CODE SCIENTIFIC NAME 6-LETTER CODE Highland Tinamou HITI Nothocercus bonapartei NOTBON Great Tinamou GRTI Tinamus major TINMAJ Little Tinamou LITI Crypturellus soui CRYSOU Thicket Tinamou THTI Crypturellus cinnamomeus CRYCIN Slaty-breasted Tinamou SBTI Crypturellus boucardi CRYBOU Choco Tinamou CHTI Crypturellus kerriae CRYKER White-faced Whistling-Duck WFWD Dendrocygna viduata DENVID Black-bellied Whistling-Duck BBWD Dendrocygna autumnalis DENAUT West Indian Whistling-Duck WIWD Dendrocygna arborea DENARB Fulvous Whistling-Duck FUWD Dendrocygna bicolor DENBIC Emperor Goose EMGO Anser canagicus ANSCAN Snow Goose SNGO Anser caerulescens ANSCAE + Lesser Snow Goose White-morph LSGW Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Intermediate-morph LSGI Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Lesser Snow Goose Blue-morph LSGB Anser caerulescens caerulescens ANSCCA + Greater Snow Goose White-morph GSGW Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Intermediate-morph GSGI Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Greater Snow Goose Blue-morph GSGB Anser caerulescens atlantica ANSCAT + Snow X Ross's Goose Hybrid SRGH Anser caerulescens x rossii ANSCAR + Snow/Ross's Goose SRGO Anser caerulescens/rossii ANSCRO Ross's Goose -

Centre De Conservation De La Faune Ailée

Centre de conservation de la faune ailée September 2010 Dear birders, I would like to share with you two important events I have experienced in the last 5 months. First, I had the privilege of participating in a three week birding trip to Kenya this past May. Second, it is with great pleasure that I introduce you to one of the In this issue : youngest birders in Québec, my daughter, who was born on August 20th. After leaving the hospital, we saw a Merlin flying very low over -Special Events us. It’s a good birding start for her. Will her passion for birds grow like her father’s? Only time will tell! -A trip to Kenya As always we anticipate and -Our new products and appreciate your feedback. suggestions Keep those comments coming! -Bird Quiz Happy Reading. Alain Goulet, owner We will be at the upcoming events: September 11th: Congrès des Ornithologues Amateurs du Québec (COAQ) in Victoriaville. CCFA - Nature Expert September 17-18-19th : Festival des migrateurs de la Haute 7950 rue de Marseille Côte-Nord in Tadoussac Montréal, QC H1L 1N7 (Métro Honoré-Beaugrand) October 9-10-11th : Fête des oiseaux migrateurs at l'étang [email protected] Burbank at Danville in Estrie www.ccfa-montreal.com If you plan to be at those birding events, please drop by our Telephone 514.351.5496 booth and see our specialized birding products. Fax 1.800.588.6134 A trip to Kenya Hours of operation From May 7th to May 27th, I Fifteen of us travelled to Kenya where Tue. -

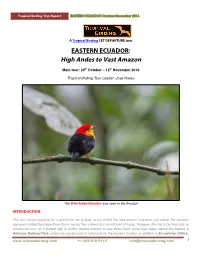

High Andes to Vast Amazon

Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 A Tropical Birding SET DEPARTURE tour EASTERN ECUADOR: High Andes to Vast Amazon Main tour: 29th October – 12th November 2016 Tropical Birding Tour Leader: Jose Illanes This Wire-tailed Manakin was seen in the Amazon INTRODUCTION: This was always going to be a special for me to lead, as we visited the area where I was born and raised, the Amazon, and even visited the lodge there that is run by the community I am still part of today. However, this trip is far from only an Amazonian tour, as it started high in Andes (before making its way down there some days later), above the treeline at Antisana National Park, where we saw Ecuador’s national bird, the Andean Condor, in addition to Ecuadorian Hillstar, 1 www.tropicalbirding.com +1-409-515-9110 [email protected] Page Tropical Birding Trip Report EASTERN ECUADOR October-November 2016 Carunculated Caracara, Black-faced Ibis, Silvery Grebe, and Giant Hummingbird. Staying high up in the paramo grasslands that dominate above the treeline, we visited the Papallacta area, which led us to different high elevation species, like Giant Conebill, Tawny Antpitta, Many-striped Canastero, Blue-mantled Thornbill, Viridian Metaltail, Scarlet-bellied Mountain-Tanager, and Andean Tit-Spinetail. Our lodging area, Guango, was also productive, with White-capped Dipper, Torrent Duck, Buff-breasted Mountain Tanager, Slaty Brushfinch, Chestnut-crowned Antpitta, as well as hummingbirds like, Long-tailed Sylph, Tourmaline Sunangel, Glowing Puffleg, and the odd- looking Sword-billed Hummingbird. Having covered these high elevation, temperate sites, we then drove to another lodge (San Isidro) downslope in subtropical forest lower down. -

Neotropical Notebooks Please Include During a Visit on 9 April 1994 (Pyle Et Al

COTINGA 1 Neotropical Notebook Neotropical Notebook These recent reports generally refer to new or Chiriqui, during fieldwork between 1987 and 1991, second country records, rediscoveries, notable representing a disjunct population from that of Mexico range extensions, and new localities for threat to north-western Costa Rica (Olson 1993). Red- ened or poorly known species. These have been throated Caracara Daptrius americanus has been collated from a variety of published and unpub rediscovered in western Panama, with several seen and lished sources, and therefore some records will be heard on 26 August 1993 around the indian village of unconfirmed. We urge that, if they have not al Teribe (Toucan 19[9]: 5). ready done so, contributors provide full details to the relevant national organisations. COLOMBIA Recent expeditions and increasing interest in this coun BELIZE try has produced a wealth of new information, including There are five new records for the country as follows: a 12 new country records. A Cambridge–RHBNC expedi light phase Pomarine Jaeger Stercorarius pomarinus tion to Serranía de Naquén, Amazonas, in July–August seen by the fisheries pier, Belize City, 1 May 1992; 1992 found 4 new country records as follows: Rusty several Fulvous Whistling-Duck Dendrocygna bicolor Tinamou Crypturellus brevirostris observed at an ant- seen at Cox Lagoon in November 1986, up to 20 at swarm at Caño Ima, 12 August; Brown-banded Crooked Tree in March 1988, and again on 3 May 1992; Puffbird Notharchus tricolor observed in riverside a Chuck-will’s Widow Caprimulgus carolinensis col trees between Mahimachi and Caño Colorado [no date]; lected at San Ignacio, Cayo District, 13 October 1991; and a male Guianan Gnatcatcher Polioptila guianensis Spectacled Foliage-gleaner Anabacerthia observed at close range in a mixed flock at Caño Rico, 2 variegaticeps recently recorded on an expedition to the August (Amazon 1992). -

June 16-23,2017

THE BIRDS OF PANAMA Early Bird Special ! Send your deposit by A BIRDER’S SAFARI HOSTED BY September 15, 2016 and receive a copy of BARB REVARD The Birds of Panama DIRECTOR OF PROGRAM PLANNING, COLUMBUS ZOO AND AQUARIUM HARPY EAGLE JUNE 16-23, 2017 ©World Safaris, 5306 Villas Ct., Winston-Salem, NC 27103 Columbus Zoo and Aquarium, 9990 Riverside Dr., Powell, OH 43065 [email protected] 336-776-0359 703-981-4474(mobile) [email protected] 614-724-3558 Barb Revard Director of Program Planning Columbus Zoo and Aquarium Join me in discovering the incredible birds of Panama! HOST DETAILS: I am so excited to travel to Panama with the Zoo and Columbus Barb has been a member of the Columbus Zoo and Aquarium team for Audubon! Panama is hands-down one of the “must visit” places on 29 years and is responsible for developing programs which enhance the any birders wish list. With more species of birds than all of North conservation education and/or entertainment experiences for Zoo and America, in a country the size of South Carolina, this will be an community audiences. She also develops community partnerships that amazing experience! And to make it even better, we will stay in the strengthen the ability of the Zoo to promote and deliver quality world-renown Canopy Tower. Along with motmot’s, toucans and education, conservation, and research projects. Having led the Zoo’s Harpy Eagles, a stay in the Canopy Tower and birding on the famed efforts in sustainability since 2008, Barbara is proud of the recently Pipeline Road are a definite tic on any birders life list! completed carbon footprint assessment and the development of a An extraordinary expedition awaits, offering opportunities for all of us Sustainability Strategy Plan to lead the Zoo as they create future to discover, together, the magic and mystery of the birds of Panama! projects aimed at reducing their carbon footprint. -

Bfree Bird List

The following is a list of species of birds that have been recorded in the vicinity of BFREE, a scientific field station in Toledo District, southern Belize. The list includes birds seen on the 1,153 private reserve and in the adjacent protected area, the Bladen Nature Reserve. BFREE BIRD LIST ❏ Neotropic ❏ Double-toothed ❏ Little Tinamou Cormorant Kite ❏ Thicket Tinamou ❏ Anhinga ❏ White Tailed Kite ❏ Slaty-breasted ❏ Brown Pelican ❏ Plumbeous Kite Tinamou ❏ Bare-throated ❏ Black-collared ❏ Plain Chachalaca Tiger-Heron Hawk ❏ Crested Guan ❏ Great Blue Heron ❏ Bicolored Hawk ❏ Great Curassow ❏ Snowy Egret ❏ Crane Hawk ❏ Ocellated Turkey ❏ Little Blue Heron ❏ White Hawk ❏ Spotted ❏ Cattle Egret ❏ Gray Hawk Wood-Quail ❏ Great Egret ❏ Sharp-shinned ❏ Singing Quail ❏ Green Heron Hawk ❏ Black-throated ❏ Agami Heron ❏ Common Bobwhite ❏ Yellow-crowned Black-Hawk ❏ Ruddy Crake Night-Heron ❏ Great Black-Hawk ❏ Gray-necked ❏ Boat-billed Heron ❏ Solitary Eagle Wood-Rail ❏ Wood Stork ❏ Roadside Hawk ❏ Sora ❏ Jabiru Stork ❏ Zone-tailed Hawk ❏ Sungrebe ❏ Limpkin ❏ Crested Eagle ❏ Killdeer ❏ Black-bellied ❏ Harpy Eagle ❏ Northern Jacana Whistling-Duck ❏ Black-and-white ❏ Solitary Sandpiper ❏ Muscovy Duck Hawk-Eagle ❏ Lesser Yellow Legs ❏ Blue-winged Teal ❏ Black Hawk-Eagle ❏ Spotted Sandpiper ❏ Black Vulture ❏ Ornate Hawk-Eagle ❏ Pale-vented Pigeon ❏ Turkey Vulture ❏ Barred ❏ Short-billed Pigeon ❏ King Vulture Forest-Falcon ❏ Scaled Pigeon ❏ Lesser ❏ Collared ❏ Ruddy Yellow-headed Forest-Falcon Ground-Dove Vulture ❏ Laughing Falcon ❏ Blue Ground-Dove