Notes Courtes

Total Page:16

File Type:pdf, Size:1020Kb

Load more

Recommended publications

-

Ethiopian Endemics I 11Th to 29Th January 2014 & Lalibela Historical Extension 29Th January to 1St February 2014

Ethiopian Endemics I 11th to 29th January 2014 & Lalibela Historical Extension th st 29 January to 1 February 2014 Trip report Abyssinian Roller by Markus Lilje Tour leaders: Wayne Jones & Andrew Stainthorpe. Trip report compiled by Wayne Jones RBT Ethiopian Endemics I Trip Report 2014 2 Top 10 birds as voted by participants: 1. Ruspoli’s Turaco 2. Abyssinian Roller 3. Half-collared Kingfisher 4. Fox Kestrel 5. Abyssinian Ground Thrush 6. Nile Valley Sunbird 7. Hartlaub’s Bustard 8. Quailfinch 9. Abyssinian Catbird 10. Abyssinian Woodpecker Tour Summary Our tour kicked off in the grounds of our hotel in Addis Ababa on what was, essentially, an arrival day. Despite its location in the middle of the bustling and chaotic capital city, the gardens yielded a good selection of birds including Wattled Ibis, African Harrier-Hawk, White-collared Pigeon, African Paradise Flycatcher, Brown Parisoma, Dusky Turtle Dove, Abyssinian Thrush, Montane White-eye, Abyssinian Slaty Flycatcher, Brown-rumped Seedeater and Ruppell’s Robin-Chat. Common Cranes by Adam Riley We set out early the following morning so as to arrive at Lake Chelekcheka just after dawn, when the hundreds of Common Cranes that roost there start becoming active amid a cacophony of guttural bugling. With waves of cranes passing over us on their way to forage in the fields, we found plenty of other waterbirds including Northern Shoveler, Spur-winged Goose, Northern Pintail, Eurasian Teal, Greater and Lesser Flamingos, Spur-winged Lapwing, Three-banded Plover, Black-tailed Godwit and Temminck’s Stint. Yellow Wagtails abounded and one of the area’s specials, the tiny and gorgeous Quailfinch, gave excellent views. -

South Africa Mega Birding III 5Th to 27Th October 2019 (23 Days) Trip Report

South Africa Mega Birding III 5th to 27th October 2019 (23 days) Trip Report The near-endemic Gorgeous Bushshrike by Daniel Keith Danckwerts Tour leader: Daniel Keith Danckwerts Trip Report – RBT South Africa – Mega Birding III 2019 2 Tour Summary South Africa supports the highest number of endemic species of any African country and is therefore of obvious appeal to birders. This South Africa mega tour covered virtually the entire country in little over a month – amounting to an estimated 10 000km – and targeted every single endemic and near-endemic species! We were successful in finding virtually all of the targets and some of our highlights included a pair of mythical Hottentot Buttonquails, the critically endangered Rudd’s Lark, both Cape, and Drakensburg Rockjumpers, Orange-breasted Sunbird, Pink-throated Twinspot, Southern Tchagra, the scarce Knysna Woodpecker, both Northern and Southern Black Korhaans, and Bush Blackcap. We additionally enjoyed better-than-ever sightings of the tricky Barratt’s Warbler, aptly named Gorgeous Bushshrike, Crested Guineafowl, and Eastern Nicator to just name a few. Any trip to South Africa would be incomplete without mammals and our tally of 60 species included such difficult animals as the Aardvark, Aardwolf, Southern African Hedgehog, Bat-eared Fox, Smith’s Red Rock Hare and both Sable and Roan Antelopes. This really was a trip like no other! ____________________________________________________________________________________ Tour in Detail Our first full day of the tour began with a short walk through the gardens of our quaint guesthouse in Johannesburg. Here we enjoyed sightings of the delightful Red-headed Finch, small numbers of Southern Red Bishops including several males that were busy moulting into their summer breeding plumage, the near-endemic Karoo Thrush, Cape White-eye, Grey-headed Gull, Hadada Ibis, Southern Masked Weaver, Speckled Mousebird, African Palm Swift and the Laughing, Ring-necked and Red-eyed Doves. -

Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK

Technical Assistance Report Protected Area Management Plan Development - SAPO NATIONAL PARK - Sapo National Park -Vision Statement By the year 2010, a fully restored biodiversity, and well-maintained, properly managed Sapo National Park, with increased public understanding and acceptance, and improved quality of life in communities surrounding the Park. A Cooperative Accomplishment of USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon- USDA Forest Service May 29, 2005 to June 17, 2005 - 1 - USDA Forest Service, Forestry Development Authority and Conservation International Protected Area Development Management Plan Development Technical Assistance Report Steve Anderson and Dennis Gordon 17 June 2005 Goal Provide support to the FDA, CI and FFI to review and update the Sapo NP management plan, establish a management plan template, develop a program of activities for implementing the plan, and train FDA staff in developing future management plans. Summary Week 1 – Arrived in Monrovia on 29 May and met with Forestry Development Authority (FDA) staff and our two counterpart hosts, Theo Freeman and Morris Kamara, heads of the Wildlife Conservation and Protected Area Management and Protected Area Management respectively. We decided to concentrate on the immediate implementation needs for Sapo NP rather than a revision of existing management plan. The four of us, along with Tyler Christie of Conservation International (CI), worked in the CI office on the following topics: FDA Immediate -

Zoologica Scripta

Zoologica Scripta A multi-gene phylogeny disentangles the chat-flycatcher complex (Aves: Muscicapidae) DARIO ZUCCON &PER G. P. ERICSON Submitted: 4 November 2009 Zuccon, D. & Ericson, P. G. P. (2010). A multi-gene phylogeny disentangles the chat- Accepted: 20 January 2010 flycatcher complex (Aves: Muscicapidae).—Zoologica Scripta, 39, 213–224. doi:10.1111/j.1463-6409.2010.00423.x We reconstructed the first well-sampled phylogenetic hypothesis in the chat-flycatcher complex combining nuclear and mitochondrial sequences. The dichotomy between chats- terrestrial feeders and flycatchers-aerial feeders does not reflect monophyletic groups. The flycatching behaviour and morphological adaptations to aerial feeding (short tarsi, broad bill, rictal bristles) evolved independently from chat ancestors in three different lineages. The genera Alethe, Brachypteryx, and Myiophonus are nested within the Muscicapidae radia- tion and their morphological and behavioural similarities with the true thrushes Turdidae are presumably the result of convergence. The postulated close relationships among Erith- acus, Luscinia and Tarsiger cannot be confirmed. Erithacus is part of the African forest robin assemblage (Cichladusa, Cossypha, Pogonocichla, Pseudalethe, Sheppardia, Stiphrornis), while Luscinia and Tarsiger belong to a large, mainly Asian radiation. Enicurus belongs to the same Asian clade and it does not deserve the recognition as a distinct subfamily or tribe. We found good support also for an assemblage of chats adapted to arid habitats (Monticola, Oenanthe, Thamnolaea, Myrmecocichla, Pentholaea, Cercomela, Saxicola, Campicoloides, Pinarochroa) and a redstart clade (Phoenicurus, Chaimarrornis and Rhyacornis). Five genera (Muscicapa, Copsychus, Thamnolaea, Luscinia and Ficedula) are polyphyletic and in need of taxonomic revision. Corresponding author: Dario Zuccon, Molecular Systematics Laboratory, Swedish Museum of Natural History, Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden. -

Voelker and Spellman.Pdf

MOLECULAR PHYLOGENETICS AND EVOLUTION Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 30 (2004) 386–394 www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Nuclear and mitochondrial DNA evidence of polyphyly in the avian superfamily Muscicapoidea Gary Voelker* and Garth M. Spellman Barrick Museum of Natural History, Box 454012, University of Nevada Las Vegas, 4505 Maryland Parkway, Las Vegas, NV 89154, USA Received 26 November 2002; revised 7 May 2003 Abstract Nucleotide sequences of the nuclear c-mos gene and the mitochondrial cytochrome b and ND2 genes were used to assess the monophyly of Sibley and MonroeÕs [Distribution and Taxonomy of Birds of the World, Yale University Press, New Haven, 1990] Muscicapoidea superfamily. The relationships and monophyly of major lineages within the superfamily, as well as genera mem- bership in major lineages was also assessed. Analyses suggest that Bombycillidae is not a part of Muscicapoidea, and there is strongly supported evidence to suggest that Turdinae is not part of the Muscicapidae, but is instead sister to a Sturnidae + Cinclidae clade. This clade is in turn sister to Muscicapidae (Muscicapini + Saxicolini). Of the 49 Turdinae and Muscicapidae genera that we included in our analyses, 10 (20%) are shown to be misclassified to subfamily or tribe. Our results place one current Saxicolini genus in Turdinae, two Saxicolini genera in Muscicapini, and five Turdinae and two Muscicapini genera in Saxicolini; these relationships are supported with 100% Bayesian support. Our analyses suggest that c-mos was only marginally useful in resolving these ‘‘deep’’ phylogenetic relationships. Ó 2003 Published by Elsevier Science (USA). Keywords: Bombycillidae; Cinclidae; Molecular systematics; Muscicapidae; Muscicapoidea; Sibley and Ahlquist; Sturnidae 1. -

THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION of the WATER REDSTARTS, CHAIMARRORNIS and RHYACORNIS the Generic Position of the Water Redstarts Is Controversial

220 SHORT COMMUNICATIONS IBIS121 THE SYSTEMATIC POSITION OF THE WATER REDSTARTS, CHAIMARRORNIS AND RHYACORNIS The generic position of the water redstarts is controversial. Recent faunistic books assign the three species to two genera: the White-capped Water Redstart Chaimarrornis Zeucocephala, the Plumbeous Water Redstart Rhyacornis fuliginosus and the Philippine Water Redstart R. bicoZor (Ali & Ripley 1973a,b, du Pont 1971). Previously, Hartert (1910) included Rhyacornis in Chaimarrornis, and Ripley (1952) united both genera with Phoeni- curus (cf. Vaurie 1955). Goodwin (1957), however, suggested that the water redstarts were allied to Oenanthe, Saxicola and Saxicoloides, and that the resemblances between Chai- nzurrornis and Rhyacornis were the result of convergence. These views were adopted by Ripley (1962), who subsequently (1964) placed Rhyacornis between Phoenicurus and Hodgsonius and Chaimarrornis between Oenanthe and Saxicoloides. Desfayes (1969) included the JVhite-capped Water Redstart in the otherwise African genus Thamnolaea, and allied Rhyacwnis spp. with Oenanthe, particularly the Red-tailed Wheatear 0. xanthoprymna. Hall Fi AIoreau (1970) have merged Thamnolaea with Myrmecocichla, but the expanded genus is still confined to Africa except for the species leucocephala. This paper reviews the reclassifications of Goodwin (1957) and Desfayes (1969). I made brief observations of White-capped and Plumbeous Water Redstarts during a visit to Kashmir and Nepal in April 1973. Plumage characters were studied on skins at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, and Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto. OBSERVATIOXS Size \Ving measurements presented by Desfayes (1969) to show similarity in size between the White-capped Water Redstart and ThamnoZaea spp. indicate little overlap. The White-capped is larger than most species of Phoenicurus (but smaller than Guldenstadt’s Redstart P. -

Acari: Syringophilidae) Parasitising African flycatchers (Aves: Muscicapidae)

CORE Metadata, citation and similar papers at core.ac.uk Provided by Springer - Publisher Connector Syst Parasitol (2012) 83:123–135 DOI 10.1007/s11230-012-9376-5 Three new species of picobiine mites (Acari: Syringophilidae) parasitising African flycatchers (Aves: Muscicapidae) Maciej Skoracki • Piotr Solarczyk • Bozena Sikora Received: 27 April 2012 / Accepted: 25 May 2012 Ó The Author(s) 2012. This article is published with open access at Springerlink.com Abstract Three new species of quill mites of the species of 53 genera recorded from more than 180 bird subfamily Picobiinae Johnston & Kethley, 1973 (Acari: species belonging to 69 families of 21 orders from all of Syringophilidae) are described from African flycatchers the geographical regions, except for the Antarctic (Passeriformes: Muscicapidae): Picobia cichladusa n. (Skoracki, 2011; Skoracki & OConnor, 2010; Skoracki sp. on Cichladusa arquata Peters and P. myrmecocichla et al., 2011, 2012). However, the actual number of n. sp. on Myrmecocichla arnotti (Tristram), both from syringophilid species is estimated to be at least 5,000 Tanzania, and P. echo n. sp. on Cossypha heuglini based on the species numbers of their potential hosts Hartlaub from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. (Johnston & Kethley, 1973). In contrast to members of the subfamily Syringophilinae Lavoipierre, 1953, which mainly inhabit the flight feathers, most species of the Introduction subfamily Picobiinae Johnston & Kethley, 1973,except for species of Calamincola Casto, 1978, occupy quills of The family Syringophilidae Lavoipierre, 1953 includes the body feathers. This difference is likely a result of a highly specialised parasites of birds. These mites live basal divergence at an early stage of syringophilid and reproduce inside the quills of various feather types evolution (Skoracki et al., 2004). -

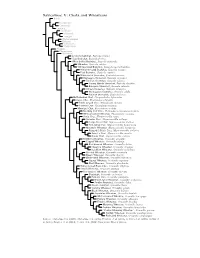

Saxicolinae Species Tree, Part 5

Saxicolinae V: Chats and Wheatears Irania Hodgsonius Cyanecula Luscinia ?Calliope Myiomela Tarsiger ?Heteroxenicus Enicurus Cinclidium Myophonus Ficedula Phoenicurus Monticola Jerdon’s Bushchat, Saxicola jerdoni Gray Bushchat, Saxicola ferreus White-bellied Bushchat, Saxicola gutturalis Whinchat, Saxicola rubetra White-browed Bushchat, Saxicola macrorhynchus White-throated Bushchat, Saxicola insignis Pied Bushchat, Saxicola caprata White-tailed Stonechat, Saxicola leucurus Stejneger’s Stonechat, Saxicola stejnegeri Siberian Stonechat, Saxicola maurus Canary Islands Stonechat, Saxicola dacotiae European Stonechat, Saxicola rubicola African Stonechat, Saxicola torquatus Madagascan Stonechat, Saxicola sibilla Reunion Stonechat, Saxicola tectes Buff-streaked Chat, Campicoloides bifasciatus Karoo Chat, Emarginata schlegelii Sickle-winged Chat, Emarginata sinuata Tractrac Chat, Emarginata tractrac Moorland Chat, Pinarochroa sordida Mocking Cliff-Chat, Thamnolaea cinnamomeiventris White-crowned Cliff-Chat, Thamnolaea coronata Sooty Chat, Myrmecocichla nigra Anteater Chat, Myrmecocichla aethiops Congo Moor Chat, Myrmecocichla tholloni Ant-eating Chat, Myrmecocichla formicivora Mountain Wheatear, Myrmecocichla monticola Rueppell’s Black Chat, Myrmecocichla melaena Arnott’s Chat, Myrmecocichla arnotti Ruaha Chat, Myrmecocichla collaris Northern Wheatear, Oenanthe oenanthe Capped Wheatear, Oenanthe pileata Red-breasted Wheatear, Oenanthe bottae Heuglin’s Wheatear, Oenanthe heuglini Isabelline Wheatear, Oenanthe isabellina Hooded Wheatear, Oenanthe monacha -

Zakouma National Park

ZAKOUMA NATIONAL PARK BIRDS Scientific name Common Name Sinclair 1 2 3 4 5 6 1 Recurvirostra avosseta Pied Avocet 172 2 Turdoides plebejus Brown Babbler 400 3 Lybius vieilloti Veillot's Barbet 306 4 Lybius leucocephalus White-headed Barbet 302 5 Lybius dubius Bearded Barbet 308 6 Lybius rolleti Black-breasted Barbet 306 7 Terathopius ecaudatus Bateleur 82 8 Batis orientalis Grey-headed Batis 568 9 Merops pusillus Little Bee-eater 282 10 Merops hirundineus Swallow-tailed Bee-eater 282 11 Merops bulocki Red-throated Bee-eater 284 12 Merops bullockoides White-fronted Bee-eater 284 13 Merops albicollis White-throated Bee-eater 284 14 Merops orientalis Little Green Bee-eater 282 15 Merops persicus Blue-cheeked Bee-eater 284 16 Merops apiaster European Bee-eater 284 17 Merops nubicus Northern Carmine Bee-eater 280 18 Euplectes hordeaceus Black-winged Bishop 684 19 Euplectes franciscanus Northern Red Bishop 684 20 Euplectes afer Yellow-crowned Bishop 686 21 Ixobrychus minutus Little Bittern 52 22 Ixobrychus sturmii Dwarf Bittern 52 23 Sylvia atricapilla Blackcap 492 24 Bubalornis albirostris White-billed Buffalo-Weaver 656 25 Pycnonotus barbatus Common Bulbul 410 26 Emberiza flaviventris Golden-breasted Bunting 736 27 Emberiza tahapisi Cinnamon-breasted Bunting 734 28 Ardeotis arabs Arabian Bustard 146 29 Neotis denhami Denham's Bustard 146 30 Eupodotis senegalensis White-bellied Bustard 150 31 Eupodotis melanogaster Black-bellied Bustard 148 32 Turnix sylvatica Common Buttonquail 132 33 Butastur rufipennis Grasshopper Buzzard 98 34 Kaupifalco -

The Birds of the Lesio-Louna and Lefini Reserves, Congo

The birds of the Lesio-Louna and Lefini Reserves, Congo Violet-backed Starling, Cinnyricinclus leucogaster, Spréo améthyste Tony King, May 2008 The Aspinall Foundation, BP13977, Brazzaville, Republic of Congo E-mail: [email protected] Birds of the Lesio-Louna & Lefini Reserves, Congo Contents Summary ii Résumé ii Introduction 1 Legislation and Management of the Lesio-Louna and Lefini Reserves 1 Site description 2 Weather records 3 Methods 5 General Results 7 MacKinnon List Results 8 River Transect Results 14 Vehicle Transect Results 15 Mist-netting Results 16 Species accounts 23 Discussion 51 Acknowledgements 54 References 54 Appendix 1. Indices of Relative Visibility (IRVs) for 175 bird species at 7 sites in the 57 Lesio-Louna and Lefini reserves. Appendix 2. Percentages of species sighted during river transects on the Louna and Lefini 63 rivers. Appendix 3. Summary of mass (g), wing and tail (mm) measurements for birds netted in 65 the Lesio-Louna Reserve 2002-2007. Appendix 4. Summary of tarus and bill (mm) measurements for birds netted in the Lesio- 70 Louna Reserve 2002-2007. Appendix 5. Number of observations of each species by site (not including netted birds). 75 Appendix 6. Number of observations of each species by month (not including netted 85 birds). Appendix 7. Liste des 317 espèces d’oiseaux connues des Réserves Lesio-Louna et Lefini, 91 mai 2008. i Birds of the Lesio-Louna & Lefini Reserves, Congo Summary The birds of the Lesio-Louna and Lefini Reserves, Congo This report collates all known information regarding the avifauna of the Lesio-Louna and Lefini Reserves, located approximately 140 km north of Brazzaville in the Batéké Plateaux region of the Republic of Congo. -

Multi-Locus Phylogenetic Analysis of Old World Chats and Flycatchers

Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution 57 (2010) 380–392 Contents lists available at ScienceDirect Molecular Phylogenetics and Evolution journal homepage: www.elsevier.com/locate/ympev Multi-locus phylogenetic analysis of Old World chats and flycatchers reveals extensive paraphyly at family, subfamily and genus level (Aves: Muscicapidae) George Sangster a,b,*, Per Alström c, Emma Forsmark d, Urban Olsson d a Department of Vertebrate Zoology, Swedish Museum of Natural History, P.O. Box 50007, SE-104 05 Stockholm, Sweden b Department of Zoology, Stockholm University, SE-106 91 Stockholm, Sweden c Swedish Species Information Centre, Swedish University of Agricultural Sciences, Box 7007, SE-750 07 Uppsala, Sweden d Department of Zoology, University of Gothenburg, Medicinaregatan 18, SE-413 90 Gothenburg, Sweden article info abstract Article history: The chats and flycatchers (Muscicapidae) represent an assemblage of 275 species in 48 genera. Defining Received 14 March 2010 natural groups within this assemblage has been challenging because of its high diversity and a paucity of Revised 25 June 2010 phylogenetically informative morphological characters. We assessed the phylogenetic relationships of Accepted 8 July 2010 124 species and 34 genera of Muscicapidae, and 20 species of Turdidae, using molecular sequence data Available online 23 July 2010 from one mitochondrial gene and three nuclear loci, in total 3240 bp. Bayesian and maximum likelihood analyses yielded a well-resolved tree in which nearly all basal nodes were strongly supported. The tradi- Keywords: tionally defined Muscicapidae, Muscicapinae and Saxicolinae were paraphyletic. Four major clades are Passeriformes recognized in Muscicapidae: Muscicapinae, Niltavinae (new family-group name), Erithacinae and Saxi- Muscicapoidea Muscicapidae colinae. -

Biodiversity Observations

Biodiversity Observations http://bo.adu.org.za An electronic journal published by the Animal Demography Unit at the University of Cape Town The scope of Biodiversity Observations consists of papers describing observations about biodiversity in general, including animals, plants, algae and fungi. This includes observations of behaviour, breeding and flowering patterns, distributions and range extensions, foraging, food, movement, measurements, habitat and colouration/plumage variations. Biotic interactions such as pollination, fruit dispersal, herbivory and predation fall within the scope, as well as the use of indigenous and exotic species by humans. Observations of naturalised plants and animals will also be considered. Biodiversity Observations will also publish a variety of other interesting or relevant biodiversity material: reports of projects and conferences, annotated checklists for a site or region, specialist bibliographies, book reviews and any other appropriate material. Further details and guidelines to authors are on this website. Lead Editor: Arnold van der Westhuizen – Paper Editor: H.D. Oschadleus CLEVER LITTLE HUNTERS: CATCHING CAPPED WHEATEAR AND MOUNTAIN WHEATEAR IN THE NAMIBIAN SEMI-DESERT Ursula Franke-Bryson Recommended citation format: Franke-Bryson U 2016. Clever little hunters: catching Capped Wheatear and Mountain Wheatear in the Namibian semi-desert. Biodiversity Observations 7.78: 1–3 URL: http://bo.adu.org.za/content.php?id=271 Published online: 8 November 2016 – ISSN 2219-0341 – Biodiversity Observations